The NBA Has a Boston Celtics Problem: How a Loaded Roster, Overwhelming Depth and Dominance Are Warping Competitive Balance Across the League

Teams that lose their franchise superstar mid‑season are supposed to crumble.

They’re supposed to plummet down the standings, hold emergency meetings, and talk about “staying afloat” until the cavalry returns. They’re not supposed to look…better. They’re not supposed to discover a coherent offensive identity, win consistently against playoff teams, and accidentally stumble into a rotation that looks deeper and more connected than the one they started with.

The Boston Celtics apparently didn’t get that memo.

With Jayson Tatum sidelined by an Achilles tear, Boston has done something very few teams in their position ever manage: they’ve gotten sharper. At last check, they were 12–0 in their latest stretch without Tatum, stacking wins over the Cavaliers, Knicks, Magic, and Pistons, and doing it in ways that feel sustainable rather than fluky.

The secret has been equal parts obvious and surprising:

Obvious: Jaylen Brown has finally stepped into a true No. 1 option role.

Surprising: The guys who were supposed to be “depth problems” have become real solutions.

This isn’t the Celtics simply surviving without Jayson Tatum. It’s a team quietly re‑wiring itself around Jaylen Brown—and in the process, becoming more dangerous for the day Tatum returns.

Jaylen Brown, Actual Offensive Engine

The biggest unknown coming into this Tatum‑less stretch was simple:

Could Jaylen Brown carry a team as the primary option, not just as a co‑star?

Brown has had monster nights in his career. He’s dropped 40 with Tatum on the floor, taken over quarters, and torn apart mismatches. But doing that as a 1A next to an established superstar is different from doing it as the guy every defense schemes for.

So far this season, he’s answered that question emphatically.

With Brown on the floor, Boston’s offensive rating sits at 121.5. When he sits, that number plunges to 109.7. That’s nearly a 12‑point swing—about the difference between the league’s best offense and one of its worst. Swings like that don’t happen unless a player is driving the entire offensive structure.

Over a recent five‑game stretch, all wins against solid opponents, Brown averaged:

30.8 points

8.0 rebounds

7.0 assists

2.8 “stocks” (steals + blocks)

on respectable efficiency (55% true shooting), while facing the other team’s best defender every night.

This isn’t a hot streak snowballing off of easy coverage. This is a wing absorbing No. 1 defensive attention, every single game, and still producing like one of the best scorers in the league.

We’ve seen Jaylen Brown have big weeks. What’s different now is the control.

Living in the Midrange, Thriving in the Mud

If there’s a shot that defines star wings in playoff basketball, it’s the long midrange jumper—the one you’re told to avoid all year, until nothing else is there.

For Brown, that shot has gone from “solid” to “signature weapon.”

He now takes 6.4 long midrange jumpers per game, the most of any player in the NBA—literally in the 100th percentile in volume. It’s not just that he’s taking them. He’s hitting 53.1% of those looks, which ranks in the 83rd percentile.

High volume. High efficiency. High degree of difficulty.

That combination puts him in the same neighborhood as Shai Gilgeous‑Alexander, Kevin Durant, and DeMar DeRozan—elite tough‑shot makers who keep offenses alive when the spacing evaporates and the possession has gone sideways.

Those are the shots that matter in May and June:

Two on the clock, drive walled off, no clean passing angle.

Iso at the elbow against a locked‑in defender.

A broken play that needs rescuing.

For Boston, Brown has been the guy who rescues those possessions. It’s not pretty math. It’s winning math.

The Handle That Won’t Go Away (But Is Getting Better)

For all his success, one criticism has followed Jaylen Brown everywhere: his handle.

We’ve seen it in turnovers against pressure, in left‑handed drives that go nowhere, in high‑stakes moments where the ball seems to squirt away at the worst possible time. It’s the nitpick that has led some to insist he can never be a full‑time offensive engine.

This year isn’t erasing that concern. But it is reframing it.

Brown now has the ball in his hands for about 27% of his minutes—98th percentile usage for his position. With that much responsibility, turnovers are inevitable. He’s averaging 4.1 turnovers per 75 possessions, which lands him in the 35th percentile.

On paper, that’s not sparkling.

On film, the story changes:

Tighter dribble combinations.

Cleaner counters when defenders cut off his first move.

More patient pacing, especially in semi‑transition.

He finally looks like he understands how to weaponize his strength and burst without over‑dribbling into trouble. He’s not Kyrie Irving. He doesn’t have to be. He just has to be good enough for teams to pay for crowding him.

And here’s where this stretch really matters: when he slides back next to Tatum, this version of Brown—smarter, more patient, more confident as a decision‑maker—won’t vanish.

He’ll just get easier matchups.

If he can do this as a No. 1, then as a No. 2 he has a real chance to become what many have only floated hypothetically:

The best second option in the NBA.

White and Pritchard: From Cold Spell to Core Shooters

Jaylen Brown’s leap matters. But it wasn’t going to be enough by itself.

For Boston to survive without Tatum, their backcourt had to do more than play defense and move the ball. Derek White and Payton Pritchard needed to score.

Early on, they didn’t.

Through the first 12 games:

Derrick White: 28% from three.

Payton Pritchard: 26% from three.

Combined, they were giving the Celtics just 29.8 points per game and doing it on sub‑50% effective field goal shooting. That’s not just a slump. That’s an offensive structure wobbling at precisely the wrong moment.

Then, seemingly overnight, everything flipped.

Over the next eight games:

Pritchard hit 45% from three on 9.3 attempts per game—outrageous volume.

White climbed back to 39% on 7.7 attempts per game.

Those are elite shooting profiles. More importantly, they’re repeatable ones. White and Pritchard aren’t suddenly doing things outside their skill set. They’re simply doing what Boston always needed them to do—at the same time.

And for White, the impact isn’t just on the offensive end.

Derrick White: The Quiet Backbone

White might be the most underappreciated two‑way guard in basketball.

With him on the floor, the Celtics hold opponents to 6.6 fewer points per 100 possessions. That’s the kind of defensive swing you normally associate with big men who camp at the rim, not guards fighting through dribble handoffs and screens.

His value is in the details:

Early stunts that blow up actions before they start.

Perfect angles on closeouts, forcing extra passes instead of drives.

On‑ball pressure that makes star guards work for every dribble.

Against Detroit, White had his “I’m back” offensive moment: 27 points, 7 rebounds, 3 assists, 4 stocks, and 6‑of‑11 from three. He went from 5 points at halftime to 25 in the second half, and you could feel, in real time, a mental switch flip.

The last piece of the puzzle—his jumper—finally caught up to the rest of his game.

Payton Pritchard: From Bench Guard to Offensive Sparkplug

Pritchard’s breakout came on a night when White wasn’t even available.

Against Cleveland, he poured in a career‑high 42 points, adding three assists, shooting 68% from the field and 6‑for‑11 from deep.

That wasn’t a microwave bench outburst. It was a guard taking full control of an NBA offense, against a playoff defense, for 48 minutes.

With Pritchard on the floor, Boston’s offense improves by 6.5 points per 100 possessions. It’s not hard to see why:

He can create off the dribble.

He bombs threes off movement and spot‑ups.

He keeps the ball pinging rather than pounding.

White and Pritchard were never supposed to be All‑Stars. They were supposed to be stabilizers—players who kept the offense functional while the stars got the headlines.

For the first month, they weren’t. Now, they are again. And their return to form is the reason Brown’s brilliance actually matters. Without credible shooting around him, his midrange magic would go to waste.

The “No Depth” Bench That Won Games Anyway

Coming into the season, the Celtics’ biggest perceived weakness was depth.

They were supposed to be top‑heavy. A tight seven‑man core and a collection of “maybe later” projects and fringe rotation guys. One injury to a starter, the logic went, and the whole enterprise would wobble.

So much for that.

Two players, in particular, have blown past expectations:

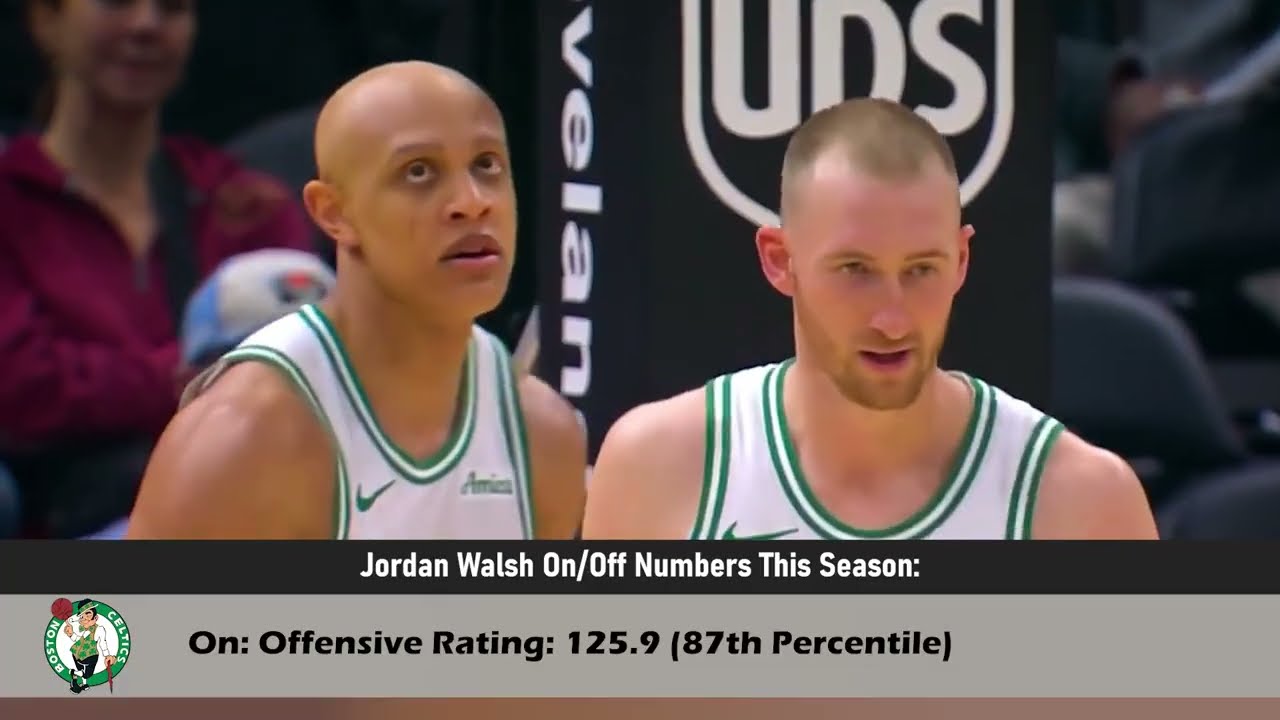

Jordan Walsh: The Glue Guy Prototype

Walsh’s box score numbers—5.3 points, 4.6 rebounds, 2 steals per game on solid shooting—don’t scream breakout. His impact does.

With Walsh on the floor:

Boston is +10.7 points per 100 possessions.

Their offensive rating hits a blistering 125.9.

He defends. He rebounds. He cuts. He doesn’t hijack possessions. He plays, in other words, like a young version of Josh Hart—doing a bit of everything, always in the right place, rarely forcing it.

Good teams need a guy like that. Great teams need two or three.

Neemias Queta: The On/Off Monster

Then there’s Neemias Queta, whose impact numbers border on unbelievable.

With Queta on the floor:

The Celtics outscore opponents by 11.9 points per 100 possessions.

Their offense is solid at 118.5.

Their defense transforms from terrible to elite.

Here’s the wild part:

Without Queta, Boston’s defensive rating is 124.2—awful.

With him, it drops to 106.6—genuinely elite.

That’s nearly an 18‑point defensive swing.

The context matters: Queta isn’t playing 35 minutes a night against starters. Some of this is matchup noise and bench‑unit dominance. But the broader truth stands: he’s a big man who protects the rim, finishes plays, and organizes the back line in ways this roster clearly needed.

This is exactly how a supposedly “thin” team survives without a superstar: the 8th, 9th, and 10th men don’t try to be heroes. They just win their minutes.

The Tatum Question

All of this success without Jayson Tatum inevitably leads to one question:

What happens when he comes back?

The noise around his potential return hasn’t stopped. There are whispers every week. A workout video here. A positive quote from someone in the organization there. Reports that Tatum himself has circled possible return dates, eager to get back on the floor.

Officially, the timeline has always been cautious:

Maybe February.

Maybe March.

Maybe not at all.

An Achilles tear is not something to rush. No one should expect “First Team All‑NBA Jayson Tatum” to walk through the door in Game 1 back and start dropping 35 a night.

But he might not have to.

If Tatum returns at 70% of his usual self—providing:

Scoring gravity.

Floor spacing.

Solid team defense.

—Boston’s ceiling jumps immediately.

If he comes back in March, spends a month playing himself into 85–90% of form before the playoffs, the entire Eastern Conference calculus changes.

A Wide‑Open East, and a Dangerous Sleeper

Look around the East and ask:

How many teams do you truly trust in a seven‑game series?

How many have both top‑end talent and consistent execution?

The answer, this year, is “not many.”

If Boston continues on something like this pace without Tatum, they could reasonably finish around 45 wins. Add Tatum back for the stretch run, steal another handful of games, and 50 wins isn’t out of the question.

That puts you squarely in the playoff picture. Not as a 1‑seed juggernaut. But as the kind of 4‑through‑6 seed no one wants to see in April:

A battle‑tested roster that’s learned how to win without its best player.

A re‑energized Tatum, playing with house money on a leg that’s finally been protected instead of overused.

A Jaylen Brown who now knows he can carry stretches, not just thinks he might.

There is, of course, another scenario.

If the bottom falls out between now and March—if the Celtics slide to 10 games under .500—everything flips. At that point, logic suggests bringing Tatum back slowly, prioritizing the long term, maybe even protecting draft position for one more foundational piece.

That would be the prudent, patient move.

It also might not be the one Tatum wants.

The Front Office’s Pivot Point

Everything we’ve learned about Jayson Tatum suggests he’s wired like the ultra‑competitive, old‑school stars before him. If he’s cleared to play, he’ll want to play. Sitting him for long‑term planning reasons when he’s medically ready would be a hard sell.

That puts Boston’s front office, led by Brad Stevens, in an interesting position as the trade deadline approaches.

If the Celtics are firmly in the mix without Tatum, a bigger in‑season move suddenly makes more sense—not just as a play for next year, but as a real attempt to crash this year’s playoff party too.

A more conservative deadline—tweaks and marginal upgrades—would suggest Stevens is eyeing the summer for the real swing, when the cap math and asset pool are easier to manage.

Either way, this much feels clear:

Something big is coming in Boston.

It might be a blockbuster trade.

It might be Tatum’s full‑scale return.

It might be both.

What’s certain is this: the Celtics have bought themselves options.

That’s not what usually happens when a franchise player goes down.

The Silver Lining of a Nightmare

Achilles injuries are, without exaggeration, one of the worst things that can happen to a star’s career. For many, they mark the end of the “best player in the league” conversation permanently.

No one in Boston wanted this test. Yet somehow, the Celtics have turned it into an unexpected laboratory:

What does Jaylen Brown look like as a full‑time No. 1?

Can Derrick White and Payton Pritchard be more than just connective tissue?

Do Jordan Walsh and Neemias Queta have real playoff utility?

What does this roster look like when it’s forced to play without the safety blanket of Tatum’s shot‑making?

They’ve gotten encouraging answers to all of those questions.

If this is how they look without Jayson Tatum, it’s hard not to wonder—dangerously, tantalizingly—what they’ll look like when he’s back, even at something less than full power.

No one wants to see a star hurt. But if there was ever a way to handle the worst‑case scenario, the Celtics may have just written the blueprint.

They didn’t sink. They didn’t just float.

They learned how to swim without their best player.

And when he returns, the rest of the Eastern Conference may find out just how dangerous that education really was.