The Defense No One Can Figure Out: How a Revolutionary Scheme Is Shutting Down NBA Offenses and Forcing Coaches to Rewrite Their Playbooks

After winning their first championship, most teams ease into the season. The Oklahoma City Thunder did the opposite.

They started 18–1.

Shai Gilgeous-Alexander is once again averaging 30 points per game, and their offense remains potent. But that isn’t what’s terrifying the rest of the league. It’s their defense—a suffocating, hyperactive, system-wide machine that, for the second straight year, has a real claim to being the best modern defense the NBA has ever seen.

Through the opening stretch, the Thunder boast a defensive rating of 103. That’s six points better than the second‑best defense (Denver at 109), a gap so large it’s usually reserved for historical outliers.

And they’ve done it while missing two of their best defenders.

Jalen Williams (JDub), an All-Defensive Second Team wing last season, hasn’t played a game. Lu Dort, a First Team All-Defense stopper, missed a significant chunk of time. Most teams would crumble under those losses.

The Thunder got better.

What they’re doing is more than just “playing hard.” It’s a fully formed defensive philosophy, drilled to the point where five players move, react, and recover as if they share a single brain.

It looks like chaos. It’s anything but.

Full-Court Misery: Ball Pressure as a Philosophy

The first thing you notice watching Oklahoma City is the pressure.

Not just in the half court, not just in fourth quarters—everywhere, all the time.

Their core principle is simple: make the ball handler put the ball on the floor and make him work for every inch of space.

On one possession against Golden State, Jonathan Kuminga had what should’ve been a dream scenario: a post mismatch against Gilgeous-Alexander. But before the ball could even get to him, rookie guard Cason Wallace was picking up Stephen Curry almost at half court, pushing him back, forcing him to start the offense uncomfortably high.

Shai fronted Kuminga to make the post entry pass more difficult. Curry tried to counter by sending Kuminga up for a screen. Even then, Wallace stayed attached, and Jaylin Williams (Jay Will) fought for position to clog the passing lane.

The play ended in a simple turnover: a pass thrown out of bounds. On the stat sheet, it’s just a bad Curry pass. On film, it’s five defenders collectively shoving the Warriors’ offense somewhere it didn’t want to be—15 feet farther from the rim than it was drawn up.

That’s by design.

Push the offense out. Stretch possessions further from the basket. Force the opponent to be perfect just to get a decent look. Most teams can’t sustain that precision for 24 seconds, much less for 48 minutes.

And when stars get tired of fighting that pressure in the half court, they start looking for shortcuts.

The Subtle Victory: Turning Stars into Bad Shot-Takers

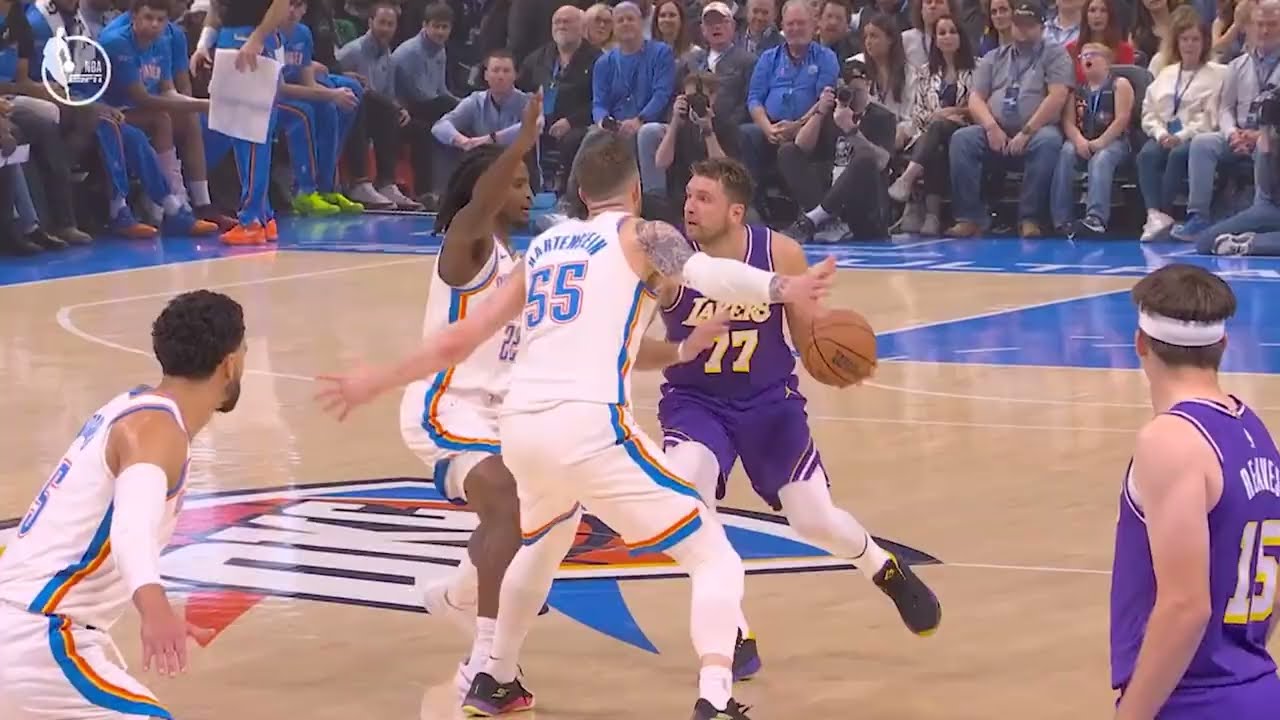

Against the Lakers, the Thunder didn’t just pick up Luka Dončić in the half court. They pressured him in the backcourt.

Multiple defenders took turns pestering him, forcing him to expend energy just to cross half court and initiate the offense.

Even while leading by more than 30 points, Wallace picked up Dončić baseline to baseline. The Lakers tried to spring Dončić free with a double ball screen. Luka, frustrated, rejected the screen and tried to lure Wallace into a foul.

Wallace slid, stayed disciplined, and kept his hands out of the cookie jar.

Individually, that’s good defense. Systemically, it’s a victory of another kind: when star players realize how much work it takes just to dribble into their spots against OKC, they start shortcutting the process. They pull up early. They take semi-contested threes. They try hero-ball drives without full advantage.

Those are the exact shots the Thunder defense wants you to take.

It’s one thing to contest shots. It’s another thing entirely to wear down superstar decision-making until they voluntarily settle for the looks your system is designed to concede. v

Small on Paper, Big in Practice

On the roster sheet, Oklahoma City has three true bigs. Everyone else who plays real minutes is 6‑foot‑6 or shorter. In a league obsessed with creating mismatches and hunting switches, that sounds like a problem.

It isn’t. Because height is only one form of size.

Gilgeous-Alexander, listed at 6‑6, has a 6‑11 wingspan. Many of his teammates are similarly rangy. More importantly, head coach Mark Daigneault has drilled a simple but powerful rule into them:

Look big. Always.

Hands up. Arms wide. Lanes crowded.

Against a player like Kuminga, Shai doesn’t need to be the taller man to win the possession. On one drive, Kuminga tried to power through him; Shai simply waited, extended his off hand, and poked the ball loose.

But the real magic happens when the ball gets inside and the help arrives.

A Packed Paint in a Spacing Era

The three-point line has never been more valued. Most modern defenses are built around limiting threes and avoiding help off shooters.

The Thunder flipped that script.

Their first priority is to protect the rim. Threes matter. Layups matter more.

Watch a typical drive against them. No matter who has the ball—All-Star or role player—there are usually at least two, often three, defenders crashing toward the paint.

That wall of bodies does three things:

-

It makes finishing at the rim extremely difficult.

It compresses driving angles to the point of claustrophobia.

It forces ball handlers to reinterpret what “open” looks like.

Daigneault’s emphasis on “looking big” comes into play here. With everyone’s arms out and hands up, passing angles seem narrower than they really are. Timing windows shrink. Risk goes up.

This is what allows the Thunder to take risks most teams would never attempt.

Breaking a Cardinal Rule—and Getting Away With It

Helping off elite shooters is supposed to be a nightmare scenario. Oklahoma City does it on purpose.

In one possession against the Lakers, Dončić posted up the smaller Wallace. Gilgeous-Alexander peeled off sharpshooter Jake LaRavia to dig down on the post—exactly the sort of help every coach warns against.

But Shai’s arms were spread so wide that the passing lane wasn’t truly visible. Dončić had to bounce the ball, which bought the Thunder an extra split-second to rotate.

The Lakers tried to repost Dončić, and Wallace “cheated” inside again, momentarily opening what looked like a lob to Deandre Ayton. Jaylin Williams raised his arms, making the passing window look tighter. By the time Dončić committed, Wallace was already in position to slap the ball away.

Later, in pick‑and‑roll, the Thunder blitzed Dončić. On film, it appeared Hayes was wide open on the roll. But with Wallace’s hands fully extended, Luka was forced to float the pass just a bit higher and softer.

That was all the time Shai needed to rotate, throw his hands up, and disrupt the next pass. Turnover. Fast break.

With everyone playing big and fast, the Thunder manipulates perception. Opponents see openings that aren’t really there, then watch them slam shut.

The Art of the Steal: Caruso and the Passing Lane Trap

Oklahoma City leads the NBA in steals at 11 per game. Even that number doesn’t quite capture how suffocating their ball-hawking truly is.

The clearest example might be Alex Caruso, one of the toughest defenders in the league to pass around.

Consider a sequence against Golden State. Trace Jackson-Davis anticipated a simple dribble handoff from Caruso’s man to Jonathan Kuminga. Caruso’s head and posture even suggested he was tracking the sideline action.

Kuminga cut backdoor—exactly the kind of counter that usually punishes overplays. Somehow, Caruso turned, extended an arm, and picked the pass off before Kuminga could gather it.

Another possession, against the Clippers: Tyrese Haliburton (or James Harden, depending on the lineup) thought he had a backscreen lob to Ivica Zubac. Caruso’s back was turned as Zoo began to roll. At the last possible split second, Caruso pivoted, threw an arm in the lane, and deflected the pass.

The throughline is anticipation and speed. Thunder defenders aren’t just gambling—they’re arriving at the right spot, at the right time, over and over again.

And when they do get beat, their recovery effort is relentless.

Playing Like There Are Six Defenders on the Court

Turn on a Thunder game and freeze the frame on almost any defensive possession. You’ll notice something odd:

It often looks like they’ve got six guys on the floor.

That illusion is created by three things:

Speed: They close space quicker than most offenses expect.

Gaps: They “sit” in between players, clogging driving lanes while still being able to contest passes.

Relentless tracking: Even after multiple rotations, they don’t relax. They sprint.

On one possession against Miami, Jimmy Butler slipped by AJ Mitchell. Isaiah Hartenstein and Chet Holmgren both crashed to help, forcing a kick-out. The ball swung to the wing, then to the corner.

The Heat had done the hard part: force two defenders to commit, then move the ball away from them.

Except the Thunder never stopped rotating. The next receiver hesitated, staring at Holmgren’s extended arms. By the time Butler got the ball back, he was stuck in an isolation with four seconds on the shot clock and four blue jerseys collapsing.

He never had a chance.

Another play against the Warriors: Golden State ran a familiar action, a Curry dribble handoff leading into a roll for a big—an action they spammed successfully against Sacramento in 2023. Kuminga popped open for a split-second.

Isaiah Joe saw it coming early. He slid down a step before the pass, closing the window. The set—drawn up, practiced, and executed—died on the vine.

Against the Clippers, they tried to post Zubac. Hartenstein fronted him, with Holmgren lurking behind. Nicolas Batum cleverly flashed to the middle, pulling Holmgren up and clearing the lob.

The entry pass found Zubac. He pump-faked, thinking he had drawn Holmgren into the air. It didn’t matter. Chet had never quit trailing the play. By the time Zoo went up, Holmgren was there to erase the dunk.

What looks like luck is repetition. What looks like chaos is choreography.

Defense Built for Modern Offense

What makes this Thunder defense uniquely terrifying is how perfectly it answers the questions posed by modern offense.

Today’s elite offenses aim to:

Space the floor with shooting.

Hunt mismatches and switches.

Generate advantages off the dribble and play out of them.

Oklahoma City’s defense attacks each of those pillars:

They’re willing to help off shooters because they trust their speed and length to recover.

They accept “mismatches” on paper, then neutralize them with help and hands.

They constantly pressure the ball, forcing offenses to burn time and energy just getting into their sets.

It’s no coincidence that even the Pacers—famous for protecting the ball and scoring efficiently—struggled to find passing lanes against OKC in the Finals, coughing up turnovers they simply don’t commit against anyone else.

With a championship and a year of experience in this system behind them, the Thunder have only sharpened the edges.

The Mark Daigneault Effect

Schemes matter. Personnel matters. But none of this happens without a coach able to teach, drill, and earn buy‑in.

Mark Daigneault arrived in Oklahoma City with little fanfare outside coaching circles. Today, he might be the architect of the most innovative defense in the league.

His principles are straightforward:

Pressure the ball.

Protect the paint first.

Look big—hands up, arms wide.

Move on a string.

Make opponents work for every advantage, every dribble, every pass.

But simple doesn’t mean easy. It requires total commitment from a roster full of young players who, in many situations, could be more focused on scoring.

Instead, you see Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, an MVP-level scorer, digging down aggressively on post-ups and flying around on defense. You see role players like Wallace and Joe sprinting back in transition, not for blocks or chase-down highlights, but to interrupt a basic dribble handoff near half court.

When your stars buy in defensively, everyone else follows.

Can Anyone Solve This?

To be fair, Oklahoma City’s early schedule hasn’t been the league’s hardest. Stronger tests are coming.

But the film doesn’t lie. What they’re doing isn’t a product of weak opposition; it’s a product of a fully committed defensive identity that most teams aren’t used to facing.

They defend with speed, length, and a mindset that every possession is a chance to make your life miserable. They ignore some modern commandments (never help off shooters, always prioritize threes) because they trust their ability to recover and strip advantages at the next point of attack.

Maybe, as the year goes on, opposing coaching staffs will find seams to exploit. Maybe a team with multiple big wings and elite passers will map out the weak spots.

Right now, no one has.

The Team Built to Check the Modern NBA

In a league where offenses have never been more efficient, where schemes and talents from Steph Curry to Luka Dončić to Nikola Jokić have shredded traditional defensive concepts, Oklahoma City may have created the closest thing we’ve seen to a system built to withstand it all.

They don’t have a traditional rim-protecting seven-footer in every lineup. They don’t always have size advantages. What they have is a shared understanding of space, timing, and pressure—and the willingness to execute it at a relentless pace.

They’re redefining what elite defense can look like in 2025: less about one towering anchor, more about five moving parts suffocating the floor.

Whether this level is sustainable over 82 games and multiple playoff runs remains to be seen. But if you’re looking for the blueprint of how to defend in the modern NBA, you start in Oklahoma City.

You start with the team that makes even the best offenses look like they’re playing against six defenders.

And right now, nobody seems close to solving them.