The Gustapo has a list. 5,000 Franks for her capture, dead or alive. By the end of the war, that bounty will climb to 5 million Franks, more than any other Allied agent in World War II. The Germans call her the White Mouse because every time they close the trap, she disappears. They don’t know her real name is Nancy Wake.

They don’t know she’s a 30-year-old woman from New Zealand who speaks perfect. They don’t know that before the war she was a socialite who loved champagne and dancing. And they certainly don’t know that she’s about to become the most decorated servicewoman in Allied history. This is the story of how one woman killed more Nazis than entire platoon of soldiers.

How she cycled 500 kilometers through enemy checkpoints in 72 hours to save a radio operator. how she killed an SS sentry with her bare hands because shooting him would wake the others. And how the Gestapo, despite hunting her with 32 agents, never caught her, not once. Nancy Wake didn’t look like a resistance fighter.

She looked like someone you’d see at a Paris fashion show. 5’7 in tall, always impeccably dressed, red lipstick even during firefights. She carried a pistol in her handbag next to her makeup compact. The Germans made a fatal mistake. They assumed a beautiful woman couldn’t be dangerous. They were wrong. Nancy Grace Augusta Wakeake was born August 30th, 1892 in Wellington, New Zealand.

The youngest of six children. Her father, Charles, was a journalist. Her mother, Ella, was a strict Methodist who believed makeup was sinful. They could not have been more disappointed in what Nancy became. When Nancy was 2 years old, the family moved to Sydney, Australia. Her father left when she was 12, just abandoned the family, disappeared.

NY’s mother became even more religious, even more controlling, even more impossible. She wanted Nancy to be a proper lady, quiet, obedient, married to a respectable man. Nancy wanted to see the world. At 16, she ran away from home, took a job as a nurse, saved every penny. At 20, she had enough money for a one-way ticket to New York.

She left Australia and never looked back. New York in 1932 was in the depths of the Great Depression. Nancy didn’t care. She worked as a journalist for Hurst newspapers, not writing fluff pieces, real journalism. She covered crime, corruption, the dark underbelly of the city. She was good at it, fearless in a way that made editors nervous and readers fascinated.

1933 she got an assignment in Europe. Travel across the continent report on the political situation. This was before the war, but the darkness was already spreading. Nancy arrived in Vienna just as the Nazis were consolidating power. She saw the brown shirts marching through the streets. She saw Jewish families being dragged from their homes.

She saw a man beaten to death with clubs while police watched and did nothing. She watched an SS officer use a whip on an elderly Jewish man in broad daylight. The man’s crime was not stepping off the sidewalk fast enough. Nancy stood there frozen, watching this casual cruelty. That moment changed everything.

She made a decision right there. If war came and it was coming, she would fight, not as a nurse or a reporter, as a soldier. She continued to Berlin, interviewed Nazi officials. She sat across from men who spoke casually about exterminating entire populations. They smiled when they said it, like they were discussing the weather.

Nancy smiled back, took notes, and filed her stories. Inside, she was calculating how many of these men she could kill if given the chance. 1936, Nancy moved to Paris. She fell in love with the city immediately. The cafes, the art, the culture, the freedom, everything her mother in Australia hated. Nancy adored. She met Henry Edmund Fiaka in 1937.

He was a wealthy French industrialist, handsome, charming, sophisticated. He owned a Marseilles soap manufacturing company and had money, lots of money. They married in 1939. Nancy became a socialite overnight. dinner parties with French politicians, opera openings, champagne on the Riviera. She wore Chanel dresses and drove a Bugatti.

On the surface, she was living the dream. But Nancy was watching the news from Germany with growing dread. Hitler had annexed Austria. Czechoslovakia was next. Poland would follow. War was inevitable. She told Henry they needed to prepare. He thought she was being dramatic. September 1st, 1939, Germany invaded Poland.

September 3rd, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Henry stopped thinking Nancy was being dramatic. For 8 months, nothing happened. The phony war. French and German troops faced each other across the Magenat line and did nothing. People started to relax. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad. Maybe there wouldn’t be fighting.

Maybe they could negotiate peace. Nancy knew better. May 10th, 1940, the Germans attacked, not at the Magenot line where France expected them, through Belgium. Through the Arden’s forest that French generals said was impassible for tanks. 1500 German tanks poured through the forest in 3 days. The French army collapsed, not retreated, collapsed. Units dissolved.

Officers abandoned their men. Soldiers threw away their weapons and fled. It was a route. June 14th, 1940, the Germans entered Paris. The city of light went dark. Swastikas flew from the Eiffel Tower. German soldiers marched down the Champsilles singing victory songs. France, the great military power, had fallen in six weeks. Six weeks.

Nancy and Henry were in the south in Marseilles. The free zone technically under control of the Vichi French government. Vichi France was a puppet state. They did whatever the Germans told them to do, which meant hunting Jews and resistance members. Nancy couldn’t sit idle. She started small. An Allied pilot shot down over France needed help getting to Spain.

Nancy hid him in her apartment for 3 days, got him false papers, drove him to the Spanish border herself. He made it. Word spread in the underground. The wealthy socialite with the Bugatti could be trusted. More pilots came, then escaped prisoners of war, then Jewish families fleeing the roundups. NY’s apartment became a safe house.

Her money funded forged documents. Her social connections provided cover stories. She attended parties with Vichy officials while hiding allied soldiers in her basement. She would dance with collaborators, laugh at their jokes, all while mentally cataloging information to pass to the resistance. The Germans noticed her eventually.

A wealthy woman whose movements didn’t quite add up. Dinner parties that ended early. Unexplained trips to the countryside. Visitors who arrived at night and left before dawn. The Gestapo started watching her. Henry begged her to stop. It was too dangerous. They would both be killed. Nancy refused.

She had seen what the Nazis did in Vienna. She would not stand by while it happened in France. 1942. The Gustapo arrested one of NY’s couriers. They tortured him for 3 days. He gave them NY’s name. The Gustapo came to her apartment at 4:00 in the morning. Nancy and Henry were asleep. The pounding on the door woke them.

Henry went to answer it. Nancy grabbed her emergency bag, always packed, always ready. False papers, money, a pistol. She went out the bedroom window while Henry delayed the Gustapo at the door. climbed down the fire escape in her night gown, disappeared into the Marseilles morning. Henry was arrested. The Gestapo questioned him for hours.

He told them nothing. He didn’t know where Nancy was, which was true. She had vanished. They released him with a warning. Next time he wouldn’t be so lucky. Nancy couldn’t go home. She moved from safe house to safe house, never staying more than two nights in one place. The Gustapo was actively hunting her.

Now, they had a description, but no photograph. They knew she was involved with the resistance, but not how high up. They had no idea she was running one of the most effective escape networks in southern France. Over 18 months, Nancy helped more than 1,000 Allied airmen and refugees escape to Spain. 1,000 people who would have been captured, imprisoned, or killed.

The Gestapo put a price on her head. 5,000 Franks. It was an insult, really. Nancy was worth far more than that. By 1943, the net was closing. Too many close calls, too many checkpoints. The Gestapo had informants everywhere. NY’s network leaders told her she needed to leave France. She was too valuable to lose.

If the Gestapo captured her, the entire network would collapse under torture. Nancy agreed, but on one condition. She would come back with training, with weapons, with the authority to kill every Nazi she could find. The escape took six attempts. Six times Nancy tried to cross the Pyrenees into Spain. Six times she was turned back by weather patrols or bad luck.

The Pyrenees in winter are brutal. Snow, ice, temperatures below freezing. People die attempting the crossing. On the sixth attempt, NY’s group was ambushed by a German patrol. Her guide was shot dead immediately. Nancy grabbed his rifle and returned fire. She had never fired a rifle before in her life. She killed two German soldiers, wounded a third, and the patrol retreated. Her group scattered.

Nancy crossed the mountains alone. It took 4 days. She had no food, no proper clothing, no map. She followed the stars and her instincts. When she staggered into a Spanish border town, she weighed 90 lb. Frostbite on her toes and fingers. Hypothermia setting in. The Spanish authorities arrested her immediately.

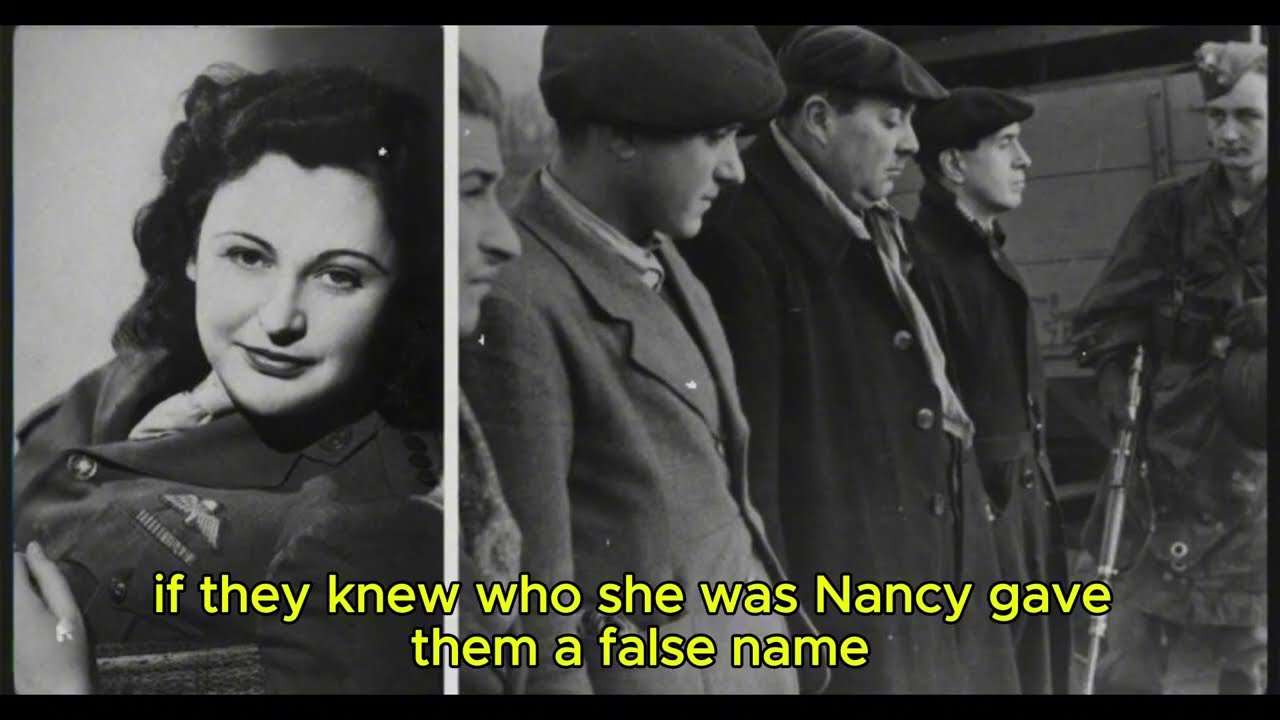

They threw her in prison for 6 weeks. Spain was officially neutral but friendly to Germany. They would have handed her back to the Gestapo if they knew who she was. Nancy gave them a false name, played the helpless refugee. Eventually, the British embassy in Madrid secured her release. She was evacuated to London. June 1943, Nancy Wake arrived in England. She weighed 97 lbs.

She had frostbite scars. She had nightmares about the mountains. And she was angrier than she had ever been in her life. She wanted revenge. The British special operations executive was recruiting. SOE was Churchill’s secret army. Agents parachuted into occupied Europe to organize resistance, sabotage infrastructure, and kill Germans.

It was incredibly dangerous. The life expectancy of an S SOE agent in France was 6 weeks. Nancy volunteered immediately. The S SOE instructors took one look at her and hesitated. She was 31 years old. She had no military training. She was a woman. Nancy didn’t care what they thought. She passed every test they threw at her.

Handto-h hand combat, weapons training, demolitions, radio operation, parachute jumps. She outperformed men half her age. The instructors wrote in her file that she was the most talented recruit they had ever seen. Also, the most difficult. Nancy didn’t follow orders she thought were stupid. She argued with instructors.

She broke rules constantly, but she got results. April 29th, 1944, Nancy parachuted back into France. She landed in the OAI region in central France. Her mission was to link up with the local Machi, the rural resistance fighters, organize them, train them, and prepare for D-Day. When the invasion came, the Machi would sabotage German reinforcements trying to reach Normandy.

Nancy landed in a tree. Her parachute got tangled. She hung there for 20 minutes before the Machi cut her down. The local commander, Captain Henry Tardevat, looked at her skeptically. London sent him a woman. Nancy looked at this group of farmers and shopkeepers with rifles and said one sentence. I hope you have wine because I’m going to need it. The mache loved her instantly.

Over the next 3 months, Nancy transformed 7,000 poorly armed civilians into an effective fighting force. She organized supply drops. She distributed weapons. She taught tactics. She led raids on German convoys. She killed personally and often. The S so SOE had taught her that hesitation gets you killed. Nancy never hesitated.

June 6th, 1944, D-Day. The invasion Nancy had been waiting for. Her Mache groups went into action across central France. They destroyed railway lines. They ambushed German convoys. They cut telephone wires. They killed over 1,000 German soldiers in the first week. The Germans sent an SS division to hunt down the resistance.

10,000 elite troops, tanks, artillery, air support. Their orders were simple. Kill everyone. The Machi scattered into the forests and mountains. Classic guerilla warfare. Hit and run. Never fight a battle you can’t win. Disappear when the enemy is strong. Nancy coordinated the resistance from a farmhouse that moved every 3 days. The Germans never found her.

One night, June 19th44, Nancy was planning a raid. Her radio operator had been killed in an ambush the day before. Without radio contact to London, she couldn’t request supply drops. No supplies meant no weapons, no ammunition, no explosives. The Machi would have to stop fighting. The nearest functioning radio was in a town called Shaderoo, 500 kilometers away.

Through German checkpoints, patrols, and occupied territory, Nancy looked at her bicycle. She looked at the map. She made a decision. She would ride to Shaderoo, make the radio contact, and ride back. 500 km there, 500 back. 1,000 kilometers total on a bicycle through enemy territory. Her lieutenants told her it was impossible.

Even if she made it past the checkpoints, the physical endurance required was beyond human capability. Nancy said she would be back in 3 days. She left at dawn. Dressed as a peasant woman, papers identifying her as a farm worker going to visit family. A pistol hidden in her bicycle basket under vegetables. The first checkpoint was 10 km out.

Two German soldiers bored, waving through most travelers. They stopped Nancy. One of them grabbed her basket, rifled through the vegetables. His hand was inches from the pistol. Nancy smiled at him. She spoke perfect German, made a joke about the weather, flirted just enough. The soldier waved her through. She cycled on.

72 hours of continuous cycling with only brief stops. She averaged 14 km per hour through rain, through pain, through exhaustion that made her hallucinate. She passed through 19 German checkpoints. Every time she smiled, flirted, acted helpless. Every time they let her through. At Shaderoo, she made radio contact with London, requested supply drops, confirmed coordination for the next wave of sabotage. Then she cycled back.

When she arrived back at the farmhouse 72 hours after leaving, her lieutenant stared at her in disbelief. Her legs were swollen. She could barely walk, but she had done it. 1,000 km in 3 days. The supply drops came the next night. The resistance continued. August 1944, NY’s Mache ambushed a German convoy, 20 trucks carrying supplies to the front.

The Germans had an SS escort. 60 soldiers heavily armed. Nancy planned a classic L-shaped ambush. hit them from two sides, create chaos, kill as many as possible, disappear before they can organize. The ambush went perfectly until it didn’t. One German truck escaped the kill zone. It raced toward a nearby village where a larger German garrison was stationed.

If that truck reached the garrison, hundreds of German soldiers would respond. The Mache would be slaughtered. Nancy was on foot. The truck was already 200 m away. She grabbed a rifle, dropped to one knee, and fired. The distance was absurd. Moving target. She wasn’t a trained sniper. The first shot missed. The second shot hit the driver.

The truck swerved off the road, crashed into a ditch, exploded. Her men stared at her. Nancy shrugged and said someone had to do it. September 1944, Nancy received intelligence about a Gustapo headquarters. The building held records of every resistance member the Germans knew about. Names, addresses, photographs. If the Germans had time to evacuate those records, hundreds of people would be arrested and executed.

Nancy decided to burn the building down. The problem was the building was in the middle of a town occupied by Vermach troops, heavily guarded. Her team said it was suicide. Nancy said it was necessary. She went in alone, dressed as a French civilian. walked right up to the building in broad daylight.

She had a basket of bread like she was delivering lunch. The guards waved her through. Inside, she pretended to get lost, wandered through hallways, mentally mapping the building. She found the records room. Three stories of filing cabinets full of names. She also found the building’s oil heating system. That night she returned, climbed through a window, placed explosives throughout the heating system, set a timer for 20 minutes, walked out the same window.

The explosion destroyed the entire building. The fire burned for 2 days. Every German record of the resistance turned to ash. Hundreds of lives saved. October 1944, Nancy encountered an SS officer in a farmhouse. The Machi was planning a raid. Nancy was scouting the approach. She entered a barn to check for Germans.

An SS sentry was inside. They saw each other simultaneously. Nancy had a knife. The German had a rifle. He started to raise it. Nancy moved. She closed the distance in three steps. She grabbed the rifle barrel with her left hand, shoved it aside. With her right hand, she drove the knife into his throat. The German made a choking sound.

Nancy held the knife in place until he stopped moving. She lowered his body silently to the ground, wiped the blade on his uniform, walked back to her team, reported that the approach was clear. No one asked questions. This was war. By the end of 1944, NY’s Mache groups had killed over 2,000 German soldiers.

They had destroyed 18 bridges. They had derailed 30 trains. They had liberated 12 towns before the regular Allied forces even arrived. And the Gestapo still hadn’t caught Nancy. The price on her head climbed to 5 million Franks, more than any other Allied agent. The Germans called her the white mouse in their reports because she was impossible to catch.

May 8th, 1945, Germany surrendered. The war in Europe was over. Nancy was in a small French town when the news came. She sat down in a cafe and ordered champagne. She drank alone, thinking about Henry, her husband. She hadn’t heard from him since 1942. She hoped he was alive. She hoped he was waiting for her. He wasn’t.

Nancy learned the truth weeks later. Henry Fiaka had been arrested by the Gestapo in 1943. They tortured him for information about Nancy for days. He told them nothing. So they executed him, shot him in the back of the head, dumped his body in a mass grave. The Gustapo killed Henry specifically to hurt Nancy.

They wanted her to know that her resistance activities had cost her husband his life. They wanted her to break. Nancy didn’t break. She got quieter, colder, but she didn’t break. After the war, Nancy was the most decorated servicewoman of World War II. Britain gave her the George Medal. France gave her the Cuadara three times.

The Maidel de la Resistance, the Legend de Hanor, America gave her the medal of freedom. She had 16 medals from three countries. She never wore any of them. Nancy moved back to London, then to Australia in the 1950s. She tried to reconcile with her mother. Her mother refused to see her. Said Nancy was a disgrace.

Too forward, too independent, too masculine. Nancy tried marriage again twice. Both failed. She drank too much. She had nightmares. She would wake up reaching for weapons that weren’t there. Post-traumatic stress disorder, though they didn’t call it that then. shell shock, battle, fatigue, or just being difficult.

Nancy was difficult. She worked odd jobs. She ran for Australian Parliament and lost. She wrote an autobiography that no one read. She outlived most of the men she fought beside. Slowly, her story began to resurface. Historians started researching SOE agents. NY’s files were declassified. People realized what she had done.

A woman who killed Nazis, cycled 1,000 km through enemy lines, and survived when the life expectancy was 6 weeks. 2010, Nancy Wake was living in a London nursing home. She was 98 years old. A journalist asked her if she had any regrets. Nancy thought about it for a long moment. Then she said she regretted not killing more Germans.

The journalist laughed nervously, thinking it was a joke. Nancy wasn’t joking. August 7th, 2011, Nancy Wake died in her sleep. She was 98 years old. They cremated her body. Her ashes were scattered in the hills of central France. The same forest where her Machi had fought and died. No funeral service, no military ceremony.

Nancy had left instructions that she wanted no fuss. She was buried quietly the way she had lived after the war. But here’s what Nancy Wake’s story teaches us. The Gustapo had unlimited resources. They had thousands of agents, informants in every village torture chambers, the full weight of Nazi Germany behind them.

They hunted Nancy for 3 years. They put a 5 million Frank bounty on her head. They sent 32 agents specifically to find her. They never caught her, not once. Because Nancy understood something the Gustapo didn’t. Power isn’t about force. It’s about will. The Gestapo had force. Nancy had will.

She had the will to jump out of airplanes into enemy territory. The will to cycle 1,000 km without sleep. The will to kill a man with her bare hands because shooting him would endanger her mission. The will to keep fighting when everyone she loved was dead. The Gestapo assumed a woman in a Chanel dress couldn’t be dangerous. That assumption killed 2,000 of them.

Nancy was 5’7. She wore red lipstick. She loved champagne and dancing. And she was the most lethal allied agent in France. The Germans called her the white mouse. Her Maki called her Madame Andre. History calls her a hero, but Nancy Wake would probably just shrug and say she was doing her job.

And that job was killing Nazis. She was very, very good at her job. When Nancy died, the French government wanted to give her a state funeral. NY’s will specifically forbad it. She said she didn’t fight for medals or recognition. She fought because sitting idle while evil spread was unacceptable. She fought because someone had to.

And she won because she refused to lose. 32 Gustapo agents hunted her. None of them survived the war. Nancy did. That’s not luck, that’s will. Pure unbreakable will. And in the end will always defeats force always.