They Trapped a Mermaid Using Shark Bait. She Told Them The Truth About the Missing Divers

I am Dr. Marcus Reed. I am 58 years old, and for 23 years I have carried a secret I never intended to share. In April 2002, the waters off the Great Barrier Reef revealed something that changed my life—and perhaps, if the world ever understands, could change everything we know about the ocean.

I was a marine biologist, specializing in shark behavior and migration. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority called me in after fourteen experienced divers vanished from a forty-mile stretch of reef near Cairns, all during night dives, all without distress signals or equipment failure. What happened next forced me to choose between truth and protection, between science and compassion.

The Vanishing

Colin Ashworth was the first to disappear, a seasoned instructor leading a night charter near Flynn Reef. He signaled he was going to photograph a moray eel den and never returned. His tank was found on the reef floor, half full, mask and regulator in place, no sign of struggle. The underwater camera was gone.

Three weeks later, two more divers vanished from separate locations on the same night. Their equipment was found, but not their bodies. By the end of February, seven more had disappeared, all during the new moon phase when the ocean is darkest.

There was no pattern in experience, equipment, or weather—only timing and location. Every incident occurred between 8 p.m. and 4 a.m., within the same corridor of reef.

The Investigation

The official theory was predatory sharks, but the evidence didn’t fit. Shark attacks leave marks—teeth, torn wetsuits, blood. These divers simply vanished, as if removed with surgical precision.

I arrived in Cairns in March, tasked with finding answers. I interviewed survivors, examined equipment, and reviewed incident reports. The reef was quiet, too quiet. On my own night dive, I heard a vocalization—low frequency, not whale song or dolphin clicks, but something intentional, repeated three times. My safety divers heard it too, but later dismissed it as a distant whale. I knew better.

The Expedition

The disappearances reached fourteen by the end of March. Night diving was suspended, but the pressure for answers mounted. I proposed a research expedition—bait lines, cameras, and patience. The Maritime Safety Authority gave me two weeks, a vessel, and full scientific authorization.

My crew included Dr. Sarah Chen, a postdoctoral researcher in marine ecology; Tom Bradshaw, my graduate student; Nina Kowalski, a documentary filmmaker; and James and Robert Ui, indigenous dive masters from the Gimui Walubara Yidinji people. I wanted their knowledge of the reef, their respect for its boundaries.

During our first meeting, Robert asked if I’d heard of “Yakyok,” the water spirits said to guard sacred places. His stories spoke of boundaries, respect, and consequences for those who trespassed. I told him we needed data, but I kept his warning in mind.

The Search

We anchored at Flynn Reef, the site of the first disappearance. The water was clear, the reef healthy, the ecosystem active. We placed cameras and bait lines at dusk and began our watch.

For hours, nothing happened. Then, at 9:47 p.m., a bait line went taut, stretching nearly horizontal into the darkness. The force was immense, rhythmic—testing, not panicking. The boat lurched as another line went rigid. James moved to the winch, but Robert stopped him. “Don’t bring it up,” he warned.

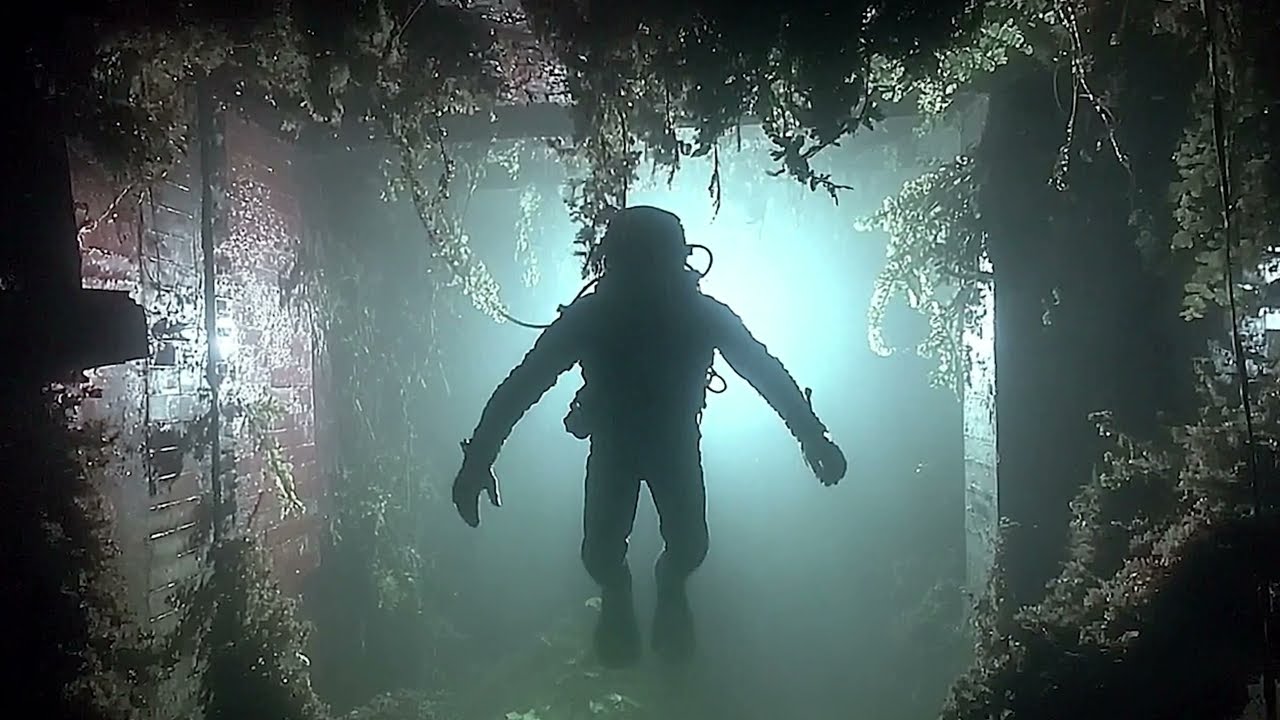

My instincts warred with caution. I activated the winch. Inch by inch, the line rose, the motor straining. At 3:02 a.m., something pale and thrashing broke the surface, tangled in the net.

The Encounter

She was roughly human-sized, smooth gray skin reflecting the lights, humanoid body but with webbed hands and a torso tapering into a tail. Her face was almost human—high cheekbones, defined nose, wide mouth. She was bleeding from the hooks, dark fluid mixing with seawater.

Her eyes were black, intelligent, moving from face to face. She made a sound—a vocalization with rhythm and intention, the same sound I’d heard underwater. She was calling, not crying.

We carried her to the holding tank, cut away the net, and removed the hooks. She watched me, pain in her eyes, but did not fight. I apologized, instinctively. She sank to the bottom, pressing her hands to the wounds.

Sarah prepared antibiotics, Tom stood silent, Nina filmed everything. Robert went below deck. James watched with unreadable expression.

Communication

At 4:15 a.m., she surfaced and looked at me. Then, in my own voice, she said, “I’m sorry.” The mimicry was perfect, but it was more than parroting. She understood context.

Her respiratory system was amphibious; she preferred to stay submerged. When Sarah tried to feed her, she examined the food and pushed it back toward the edge of the tank—a deliberate refusal, possibly a message.

I tried establishing dialogue. I pointed to myself, “Marcus,” and to Sarah, “Sarah.” She repeated our names in our voices, then pointed at herself—a gesture so human it made my chest tighten. She had no word for herself we could understand.

We tried simple words and gestures. She responded quickly, nodding or shaking her head for yes or no. She was learning, not just repeating.

The Truth

At 1 p.m., I showed her photographs of the missing divers. Each time, she retreated to the bottom of the tank, making a low, rhythmic sound—grieving, Sarah thought. She knew about the disappearances.

I pressed my palm to the glass. She matched the gesture. The connection was immediate—images, sensations, emotions not my own. Darkness, caves, territorial anger, protective rage. Humans descending with lights, entering sacred spaces. Her people defending their territory.

Some divers had been taken as warnings, others in defense, some by mistake. She felt guilt about the accidents. Her people were not monsters, but intelligent beings trying to survive as their territory shrank.

I asked why they didn’t leave. She showed me the reef—the caves, formations, currents, and prey they depended on. Moving would mean abandoning generations of adaptation. They couldn’t just leave.

She showed me more: 40 of her kind waiting below our boat, debating whether to attack. She’d argued for patience, but time was running out. If we didn’t release her in three days, they would act.

The Choice

I called a meeting. I explained what I’d learned. Sarah argued for contacting authorities, Tom worried about tourism, Nina considered the value of the footage. Robert spoke of old agreements—respecting boundaries, sharing space.

We debated responsibility, justification, and the consequences of disclosure. Without evidence, our story would be dismissed. With evidence, her people would be hunted, studied, possibly exterminated.

We agreed to release her at dawn, document a vague predator warning, and recommend indefinite closure to night diving. Protect her people by preserving their secret.

Release

I prepared for release, checked her wounds, ensured she was strong enough. At sunrise, we positioned the boat above the deepest trench. James and I rigged a sling to lower her gently.

Before release, I pressed my hand to her arm. She showed me gratitude, hope, and a warning—others would come who wouldn’t listen. The cycle would continue until one species was gone.

We lowered her into the water. She disappeared into the blue darkness, safe for now.

Aftermath

We dismantled our equipment, filed a report: “Large predator, territorial behavior, recommended closure.” The Maritime Safety Authority accepted it, disappointed. The families never got closure. The official line was an unknown predator.

Our team disbanded. Sarah moved to the Caribbean, Tom to aquaculture, Nina’s footage was never aired. James and Robert never dove that section of reef again.

I kept the secret. The nightmares began—divers preserved in caves, eyes open, cared for by her people. I shifted my research to marine protected areas, advocating for closures without naming the real reason.

The Present

The closure remained for years, but economic pressure mounted. In 2023, part of the reef reopened. Another disappearance followed, and the cycle resumed.

A filmmaker contacted me, planning to dive and film in the restricted zone. I warned her, but she dismissed my caution. The truth, I realized, must be told—not to incite curiosity, but to urge respect.

Epilogue: The Agreement

The pearl Robert gave me sits on my desk—a reminder of the fragile agreement we made. We protected her secret, and in return, her people spared us.

Publishing this account may end that agreement. Her people may see it as betrayal, but I hope they understand my intent: to prevent something worse.

To those who dive at Flynn Reef, remember: you are entering someone’s home. Respect the boundaries. To her people, I am sorry. I kept your secret, but silence is no longer enough.

To the families, I am sorry for the loss. Your loved ones were not victims of mindless predators, but casualties in a conflict over territory. That knowledge may not bring comfort, but it brings understanding.

There are people in the ocean, older than our boats, our lights, our technology. They will defend their home. The question is whether we can learn to respect that defense, or whether we will push them into extinction.

After 23 years of silence, I had to tell the truth. Even if it changes nothing, even if it makes things worse. She looked at me with those black eyes and showed me a world we are destroying, even if we are too arrogant to see it.