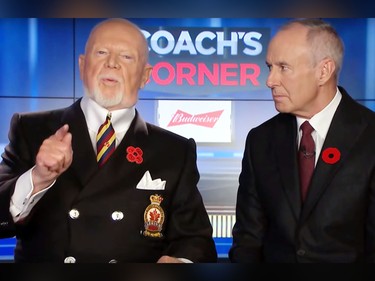

Ron MacLean and Don Cherry will forever be connected from their long-running Hockey Night in Canada segment on CBC, but now there’s bad blood between the two.In a new interview this week, Ron MacLean revealed a pneumonia scare for Cherry in the 2018 playoffs caused him to seek a way out of Sportsnet. Now Cherry’s calling BS, and is clearly furious with his old friend.

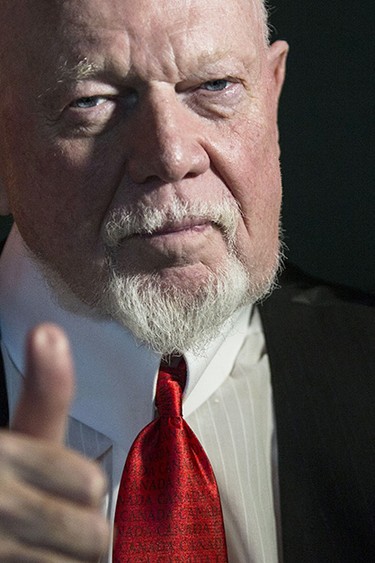

Don Cherry furious with Ron MacLean, says he is no longer welcome to speak with him

After revealing his personal health information and digging through his past, Cherry is furious with Ron MacLean. Cherry conducted a short interview today in response to MacLean, saying how disappointed he is – and that he’s no longer welcome at his house.CHERRY: I’m very disappointed in Ron, that he would bring this up. I’m very disappointed in him, that he would reach back 5 years and do this.

INTERVIEWER: Is he still welcome here, and to call you?

CHERRY: Not with the wife he isn’t. I don’t have any feelings. I don’t have any feelings towards Ron.

Cherry is now 91 years old, and still going strong on his GrapeVine podcast. There was some speculation that his last podcast episode sounded like a final sign-off from broadcasting, but Cherry has since assured fans he won’t be stopping.

It’s absolutely shocking to see how poorly their relationship has soured now in the years since Cherry’s firing. MacLean wasn’t right to air Cherry’s personal medical history to the world, and Cherry is right to feel incredibly disappointed in an old friend.

Don Cherry, one of the greatest Canadians in the nation’s history — for a time

What people want to know these days about the hockey coach, bad-boy television persona and Kingston icon is whether they’ll hear from Grapes again

Article content

On a July morning, Dan and Theresa Mosier put on their sunglasses and park as usual in their chairs on the porch, waving at passersby driving into the village of Marysville, Ont., or neighbours on foot, waiting for grandkids to drop in. This is their retirement idyll.

Dan had been the proprietor of the Oco gas station next to their house for 35 years, but he boarded it up three years ago. In bygone days, it’d be open for business, cars pulling up to the pumps, tourists unfamiliar with Wolfe Island walking into the shop to ask for directions.

“They’d wanna know how to get to the ferry to Cape Vincent and they wouldn’t even notice the guy reading the newspaper in the back, till he peeked over the top of page and they’d say, ‘Jeezus H. Christ, it’s Don Cherry, from Coach’s Corner,’” Dan Mosier says, affecting sputtering, stuttering amazement that he had seen hundreds of times. “’What’s he doin’ here?’ And I’d tell them, ‘Grapes, he’s always here.’”

Fall, winter and spring for 37 years, Cherry sat in front of the cameras in the Hockey Night in Canada studio. Summer, though, brought his retreat to Wolfe Island and even on a sunny day, he’d make himself at home in the back of the shop by the cash register, shooting the breeze with Mosier.

Out-of-towners would see the old Lincoln Continental sitting out front and imagine the station owner was a vintage-car collector, but locals knew that meant Cherry had come into the village from his cottage to see his buddy — not that they’d crash the get-together.

“They’d know he was here, but people on the island were always good about giving Don his space,” Theresa says.

“He came here every summer to get away from the crowds, not to find another one,” says Dan, who, in cadence and volume, sounds eerily like Cherry. “You can see Kingston from here, but we’re not the city. He grew up in Kingston, spent a lot of time there, but when he got Coach’s Corner and all that other stuff, it wasn’t like he’d get the sort of quiet even in his hometown that he’d get on Wolfe Island.”

It took a village to guard Cherry’s privacy. “I had people and reporters asking me for his number,” Dan says. “No way I’d give it up. They’d get it from someone else and it would get back to Grapes and he’d say, ‘You stoned them … knew I could trust you.’”

Cherry sold his cottage back in 2019, and Mosier reckons he last spoke to him on the phone two years ago. Some Wolfe Islanders are willing to share stories, but others aren’t interested in talking to a nosy outsider. The Mosiers clearly enjoy reliving the old days, although even Dan holds some stuff back. “Don told me some stuff in confidence and they’re gonna stay that way, but there’s stuff people should know about him,” he says.

What people want to know about Don Cherry these days is whether they’ll hear from him again. The question hung out when he signed off on his Grapevine podcast in June — his son Tim had told listeners this was “the last episode” and those familiar with Grapes’s voice and delivery thought he sounded wracked with emotion, his trademark, “Toodle-e-doo,” something more than wistful. He seemed to be struggling to get through the chat with Tim, who has produced the podcast since Hockey Night in Canada and Rogers Communications Inc. dropped Coach’s Corner in 2019. He had held down his TV gig into his mid-80s, always able to dial it up on cue, but this had been an annus horribilis: His daughter Cindy died in the summer of 2024 at the age of 67, and his younger brother Dick died in March.

The Toronto Sun’s Joe Warmington has been the unofficial Grapes whisperer since he was a reporter with the Kingston Whig-Standard 20 years ago. Through Warmington, Tim Cherry put out the message that the sign-off marked only the end of the season. “Seems the reports of Don Cherry’s retirement have been greatly exaggerated,” Warmington wrote.

Among those who suspected Cherry wouldn’t be back was Ron MacLean, his sidekick on Coach’s Corner for 33 years. Other than those who share Cherry’s DNA or his second wife, Luba, no one could claim to know him better than the one he often referred to as Dummy. Listening to the Grapevine podcast after Cindy’s death, MacLean picked up a heartbreak that would make it unbearable to go on.

“That time Don and Tim and Cindy would have together each Sunday recording the podcast was magical,” MacLean said. “This season of the podcast would have been a constant reminder of the loss of Cindy. He’s definitely in a weakened state physically, (but) whether it’s the end, that’s for Don to say.”

MacLean did say that Cherry’s hospitalization with pneumonia at the end of the 2019 playoffs made him recognize that his run with Coach’s Corner was no longer sustainable. “That experience had him ask himself, ‘Why is this grind suddenly so damn hard?’,” MacLean said. “Don said, ‘I haven’t lost a step mentally and I’m in fairly good shape, but I’m now leery of putting myself through it again.’”

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

In comments made to Warmington following the recently published interview with MacLean, he “was very disappointed with Ron” and that MacLean was no longer welcome in his home. MacLean issued an apology to Cherry and regrets for being so forthcoming about his friend’s health, but he didn’t walk back the facts he volunteered.

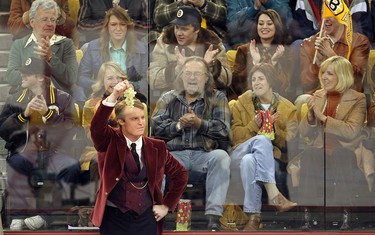

Six years after his departure from Hockey Night in Canada, it’s worth remembering the heights of Don Cherry’s celebrity, renown and respect. In 2004, the CBC embarked on an ambitious project: a vote to select the Greatest Canadians in the nation’s history. Few knocked the top slots: No. 1 was Tommy Douglas, though some might have made the case for Terry Fox who was runner-up or Sir Charles Banting not far behind. Critics would have to come out against universal health care, the Marathon of Hope and insulin.

Don Cherry landed at No. 7 on the list. It lit up arguments — too low, said his fans; an abomination, said his critics. The merits of the poll were debatable, but it captured the influence of Cherry, then 70 years old and into his third decade as Hockey Night in Canada’s first-intermission spot.

Hard to project where Cherry would land on that list today — in 2004, he benefited from recency bias, but fading memories alone wouldn’t account for a fall down the list. Reputations made over decades can crash in a flash after the shouting. Look no further than Cherry’s fellow Kingstonian one slot behind him on the CBC list, Sir John A. Macdonald, whose legacy achievements were reappraised and judged unconscionable, his name stricken, his sculpted likenesses removed, 130 years after his death. Cherry’s carving of new Canadians not wearing poppies on Remembrance Day wound up being a firing offence in 2019, but other rants as inflammatory and offensive in the ’80s and ’90s were punished by wrist slaps, if at all. None of it figures to age well.

Cherry’s history is most likely to stay fixed longest in his hometown of Kingston and particularly on Wolfe Island, where he retreated from the spotlight every summer at the height of his fame.

When the legend becomes fact, print the legend: This line from The Man who Shot Liberty Valance comes to mind with the Don Cherry biopic, Keep Your Head Up, Kid!, which in 2011 earned an erstwhile unknown former junior-hockey player named Jared Keeso a Gemini for a convincing version of Grapes in his minor-league struggles and ascendance as a coach. Tim Cherry, Don’s son, wrote and produced the film and emphasized the elements of his father’s legend that appeal to his legion of fans. With the Keep Your Head Up, Kid! screenplay, the worshipful son printed his father’s legend.

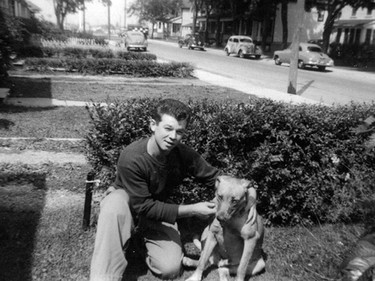

In the scene encapsulating Cherry’s boyhood, a grade-school teacher scolds Donald S. Cherry, and the kid seethes at his desk, setting up a lifetime of bucking authority. There’s no knowing how formative such challenges in the classroom were in his development, but it sets the movie’s narrative arc for the bad-boy television persona — we want this as our truth.

This legend-buffing scene selection stands in stark contrast to a photo that landed in the pages of the Whig-Standard on Nov. 9, 1946, when Cherry would have been 12 years old and he’s listed as Don Cherry of 518 Albert Street.

The caption reads: “Rideau school youths take their sports seriously, as this picture above proves. The group, members of hockey and baseball teams, meet daily before school and during recess to discuss with Nelson Silver, caretaker, the various aspects of athletic competitions which have taken place the day before. Members of this ‘Hot Stove League’ are voted in and no more than a dozen ever meet at the same time.”

Here he doesn’t look like a kid who bucks authority — he’s an earnest boy craving to learn from those who know the games he wants to play better than him, including Mr. Silver, the necktie-wearing janitor.

“My father told me there were always old-timers around town who played at a high level,” says Doug Gilmour, whose father Don, a corrections officer, played hockey and baseball with Don Cherry growing up in Kingston. “The coaching they got was as good as the coaching in the pros and even better, and they couldn’t get enough. And everyone looked up to the best players in town.”

Way back in the day, the best on the diamond and gridiron had been Cherry’s father, Delmar. According to the century-old stories in the Whig-Standard archives, Del Cherry did everything but hit the cover off the ball and had a chance to play for Syracuse in the International League, a step away from the majors, but he chose to stick around Kingston to play for hometown teams. On the football field, the Hamilton Tigers tried to get him to play pro ball, their manager comparing the 6-foot-2, 230-pound powerhouse to Lionel Conacher as an athlete, but he again took a pass.

Long after his playing days, Del Cherry was a fixture in the Kingston sports community, a coach, a goal judge at the arena, and his lore lived on when his sons started playing, first Don and then Dick — the two boys lived and played in a considerable shadow.

Del didn’t figure in the screen telling of Don’s life, and in the abridgement, neither did his mother, Maude, who worked as a tailor at the Royal Military College and later as a receptionist at the James Reid Funeral Home. Early on in his broadcast career, Cherry would mention Maude on Coach’s Corner and rail about the city of Kingston not repairing the sidewalk in front of her house. By all accounts, Maude was particular about manners and etiquette and held considerable sway. Says Dan Mosier: “I think that it was our generation and Grapes’ mom, but for all the way he was on Coach’s Corner, he’d never swear in mixed company, and he was real polite, like he was afraid of making a bad impression.”

Again, print the legend.

Keep Your Head Up, Kid! did capture the journeyman’s desperation in the early ’70s when he struggled to make a living away from the arena, when he hung up the blades after the 1969-70 season. His father always had a square job that he couldn’t be coaxed to drop no matter who made promises of sports glory. Don’s brother Dick had a degree and went to teacher’s college, so he had something he loved as much as hockey to fall back on. “I was going from construction site to construction site begging for jobs,” Don Cherry said in 2010 when he was promoting the movie. “I had no money. That was my lowest point.”

Even less promising were his prospects when he tried a comeback as a player in his 30s, only to wind up as a Black Ace with the Amerks. The Rochester Americans, AHL affiliate of the expansion Vancouver Canucks, was losing too many games and too much money for the parent club’s comfort. When the Canucks fired the coach midseason, they installed Cherry as his successor, even though his bench experience was limited to volunteering with a Rochester high-school team. Vancouver management wound up selling the franchise to a local businessman and dropping their affiliation that summer, leaving the owner and the coach with no source of players, little more to work with than the team name.

Going into the ’72-’73 season, Cherry was the farthest thing from braggadocious. He had to put together a roster comprised of everyone else’s sorry leftovers, a disaster scenario. As he told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: “There are days when I was so tied up with this job I’ve forgotten to eat. I’ll go home at night and realize I didn’t have a bite of food all day.”

Rod Graham knew none of this intrigue. Back in the summer of ’72, Graham was a journeyman minor-leaguer back in Kingston after a stint with a team in Austria. Out of the blue, he got invitation to the California Golden Seals (an NHL team that played in Oakland until 1976) — he figured the Seals holding their camp in his hometown was a way to cut costs.

“I skated with them in the first practice at the Memorial Centre and that night I got a call from Don Cherry who was coaching in Rochester,” Graham says. “He tells me, ‘You can’t be skating with Oakland ‘cause I’ve got your name on my list. If you’re skating for anybody, it’s me.’”

Unbeknownst to him, Dick Cherry had called his brother and recommended adding Graham to the Americans’ protected list. “Dick told Don I was pretty ‘handy,’” he says, the gentle euphemism preferred by tough guys.

Cherry was scrambling to find players to fill out the roster, so he put out a call for tough guys — if they couldn’t score, they could at least go to war. Graham decided to go along for the ride — at age 25, he had given up any boyhood dreams of the NHL, content to play the game for fun and draw a minor-league paycheque. He had no idea that the 38-year-old Cherry would become his improbable ticket to The Show.

Graham was one of 10 players to come out of training camp and into the Americans’ lineup on opening night without a game of AHL experience. To set the dynamic, Cherry had one pro journeyman, a pivotal get: Battleship J. Bob Kelly, one of the most ferocious brawlers of the era. With Kelly as the action hero out in front of them, Graham and other rookies no less handy followed his lead. They couldn’t beat the more talented NHL affiliates with skill, but they managed to put the fear of God in them.

Cherry’s scheme was born of necessity, but he soon proved a master motivator. “Don got the most out of everybody,” Graham says. “He knew how to talk to the players — knew what each one of us needed, and that’s not treating everyone just the same. He was smart socially. We’d run through walls for him.”

He explained his method in his first full season. From the Rochester daily in October 1972: “The old way of coaching was to treat everybody the same, but that doesn’t work because everybody is different, I played better when I was screamed at because I played better angry. (Veteran minor-leaguer) Darryl Sly played worse when someone screamed at him. Pushing hurt him. Pushing helped me.”

Cherry’s approach sounds only reasonable now, but this was radical in the era of the bad-cop coach. Being real life and not a movie, the Americans’ run wasn’t quite storybook stuff — there was no championship, but they won more than they lost and turned a profit. “They were drawing 2,000 a game before, but Grapes’ team was getting crowds of 5,000,” Graham said.

Battleship Kelly wound up getting signed by the St. Louis Blues after that season, so for his second season as Rochester coach, Cherry picked up another player unwanted by everyone else, John Wesink. If Kelly was a fierce but honourable soldier, then Wesink’s cold-bloodedness and unpredictability made him the nearest thing to a terrorist, a man without boundaries.

This time the Americans made the playoffs, but they lacked the talent to get out of the first round. To Graham’s mind, his coach had found his niche. “I figured he had a job for life in the minors, but I didn’t see him going to the NHL,” he says. “I didn’t see myself going either.”

It turned out Bruins GM Harry Sinden knew Cherry well. Two days after coaching the Bruins to the 1970 Stanley Cup, Sinden had walked away from the organization in a dispute with ownership and took a job as director of sales with a modular-home company in Rochester. When he signed with the Bruins as their managing director in the fall of ’72, Sinden told the Rochester daily: “I know Don Cherry and his family and they’re the best. Anything I can do for him, I’ll do it.”

In the summer of ’74, Sinden hired Cherry to coach the Bruins, a proven contender featuring Bobby Orr, the greatest talent the game had ever seen, Phil Esposito, the game’s most prolific scorer, and other future Hall of Fame players.

Cherry could have stayed the course in Boston, but instead decided to dance with the ones who brung him, calling up Wesink for a long stretch and Graham, who’d last only 14 games, charter members of what Cherry would tag “Lunchpail A.C.”

Advertisement 13

Story continues below

Graham’s moment of glory was a story retold over the years and offered a glimpse into the antic times and Cherry’s embrace of the playing everyman, players like himself.

“We were winning 7-0 in Minnesota and we had a powerplay,” Graham says. “Johnny Bucyk said, ‘Grapes, put Rod out there. He might even score one.’ When I hop over the boards, I stepped on Grapes’ foot. He had brand new Florshiem shoes and I sliced the one wide open with my skate blade. Then five seconds in I get the puck and it’s in the back of the net. It was like Christmas and New Year’s rolled into one.”

It turned out to be April Fool’s as well.

“So after the game, we go back to the hotel and there’s a get-together when the big guys say something. Espo gets up there, and says, ‘We were gonna give Rod the puck he scored on, but Grapes, we figured you really deserve something for putting Rod out there on the powerplay …”

And keeping Hall of Famers on the bench to give a journeyman, one Cherry could identify with, a chance at a moment of glory he never enjoyed in his single NHL game. The subtext understood by the Bruins, who knew what was coming and kept straight faces.

“‘… So we figure you deserve a piece of it,’ and Espo has a puck with a Stars logo on it sawn in half. Grapes said, ‘Sawing a guy’s first goal in half, how the hell can you do that to a guy!’ And then they let him in on the gag — they just did it with an extra puck they brought back from the rink. I had my puck.”

Graham would head back to the minors for the rest of that season and three more, dividing time between Rochester and Springfield, before heading back to Kingston for good in 1978 and taking a job with the city. He fell out of touch for a time with Cherry and didn’t know that in the summer of ’79, after the Bruins dropped him, he was visiting Wolfe Island with a friend from Rochester, Doogan Collins, who owned a cottage there.

“Back in the ’70s and ’80s it was a farm community,” says Steve Fargo, who until this spring owned the general store in the village of Marysville, just down the main drag from the Mosiers’ place. “Not really second homes or vacation places. Kind of a self-sufficient place.”

According to a story by former Whig reporter Pat Kennedy in 2019, Cherry asked Collins about a vacant lot near his cottage on Oak Point Road. “Dad walked the property,” Cherry’s son Tim said. “He said, ‘This would be a great place to build a cottage.’ Collins told him to forget it, that he’d been trying to buy the lot for years and the guy wouldn’t sell. Dad had Collins set up a meeting with the guy anyway, and when the two men met, they came to an agreement right then and there.”

Cherry would later talk about his love of fishing on the waterfront after school. He would have seen Wolfe Island across the water, would have seen the ferry going back and forth, but the Oak Point Road property seemed more an impulse buy than any sort of boyhood dream come true.