From P-51 to Enemy Fighter: One Pilot’s Daring Escape

In the annals of World War II aviation, countless stories of courage, ingenuity, and survival have been recorded. Yet, among these, the tale of Bruce Carr stands out as one of the most improbable and daring escapes ever attempted by a downed pilot. On November 2, 1944, Carr—an ace P-51 Mustang pilot—was shot down over Czechoslovakia, deep behind enemy lines. With no radio, almost no supplies, and winter closing in, the “safe” option was surrender. Instead, Carr did the unthinkable: he infiltrated a Luftwaffe airfield, stole a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter, and flew it home through a gauntlet of enemy and friendly fire. His story is not just one of technical skill and luck, but of relentless determination and the refusal to accept defeat. This essay explores the life, character, and actions of Bruce Carr, tracing his journey from a farm in upstate New York to the cockpit of a stolen German fighter, and beyond.

Early Life: The Making of a Pilot

Bruce Ward Carr was born on January 28, 1924, in Union Springs, New York. His childhood, by most accounts, was unremarkable—except for one critical detail. At the age of 15, Carr learned to fly. In 1939, as Europe was plunged into war, Carr was in the air, guided by a local crop duster named Earl. By the time Carr turned 16, he had logged more stick time than many Army Air Corps cadets. This early exposure to flight was more than a hobby; it was the foundation for a career that would span three wars and over 500 combat missions.

When Carr enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces on September 3, 1942, his experience set him apart. His instructor at aviation cadet training turned out to be Earl, the same man who had first let him take the controls. Seeing Carr’s 240 logged flight hours, Earl recommended him for the accelerated program. By August 1943, Carr was a flight officer, and by February 1944, he was in England, assigned to the 380th Fighter Squadron, 363rd Fighter Group, Ninth Air Force.

The P-51 Mustang: A Pilot’s Dream

Carr’s first combat assignment was flying the P-51 Mustang, widely regarded as the finest propeller-driven fighter of the war. The Mustang’s statistics were impressive: a range of 1,650 miles with drop tanks, a top speed of 437 mph at 25,000 feet, and a service ceiling of nearly 42,000 feet. Armed with six .50 caliber Browning machine guns and nearly 2,000 rounds of ammunition, the Mustang could shred enemy bombers in seconds.

Before the Mustang’s arrival, American bombers suffered devastating losses over Germany. The Mustang changed everything, allowing fighters to escort bombers all the way to Berlin and back. German pilots called them “the long-nosed bastards,” and the Luftwaffe began losing experienced pilots faster than they could be replaced. Carr instantly fell in love with the aircraft, naming his plane “Angel’s Playmate.” He could not have known that, within eight months, he would be flying a very different fighter—one with German labels and a swastika on the tail.

Combat Over Europe: The Path to Ace

Carr’s first combat engagement came on March 8, 1944, when he chased a Messerschmitt Bf 109 over Germany. The German pilot tried to escape by diving close to the treetops, but Carr followed, firing rounds that missed until one clipped the 109’s left wing. The German panicked, pulled up, and ejected too low for his parachute to deploy. The pilot was killed, and the aircraft crashed. Carr returned to base expecting congratulations, but his commanding officer chastised him for reckless flying and transferred him. The kill did not count—technically, Carr had not shot the plane down.

This incident was the first indication that Carr did not think like other pilots. Where others saw recklessness, he saw opportunity. Where others saw limits, Carr saw suggestions.

In May 1944, Carr transferred to the 353rd Fighter Squadron, 354th Fighter Group—the Pioneer Mustang Group, the first Army Air Forces unit in Europe to fly P-51s in combat. These were the best Mustang pilots of the war, and Carr fit right in.

On June 17, 1944, just eleven days after D-Day, Carr scored his first official kill, sharing credit for an Fw 190 destroyed over Normandy. Two months later, he was promoted to second lieutenant. On September 12, 1944, Carr’s flight strafed a German airfield, destroying several Junkers Ju 88 bombers. On the return flight, they spotted thirty Fw 190s below. Carr dove, shooting down three German fighters in three minutes. When his wingman took damage, Carr escorted him back to friendly territory, forgoing further kills to protect his fellow pilot. This act earned him the Silver Star, the second-highest combat decoration for valor.

By October 29, 1944, Carr had downed two more Bf 109s over Germany, bringing his total confirmed kills to 7.5—officially making him an ace.

Shot Down: The Ordeal Begins

Four days later, on November 2, 1944, Carr’s luck ran out. Leading a strafing run against a German airfield over Czechoslovakia, his P-51 took a hit from an 88mm shell fragment that severed the oil line. The Merlin engine began to scream as metal ground against metal. With oil pressure at zero, Carr had about ninety seconds before the engine seized. He pulled back the canopy, rolled the Mustang inverted, and dropped into the freezing sky.

At 8,000 feet, his parachute deployed. Below him stretched enemy territory—200 miles behind German lines. Carr had no radio, no weapon except a .45 pistol with seven rounds, no food, and no water. The temperature was dropping below freezing at night. The odds of evading capture and returning to Allied lines were about 23 percent; the rest ended up in POW camps or unmarked graves.

Carr hit the ground hard, twisting his ankle but avoiding a break. He buried his parachute under leaves, knowing German patrols would soon be searching for him. The airfield he had just strafed was five miles north. The Germans would expect him to move south or west toward Allied lines. Survival depended on doing something unexpected—so Carr headed north, toward the enemy.

Four Days Behind Enemy Lines

Day one was spent moving through the forest, staying off roads and traveling at night. Carr’s flight suit provided little warmth, and his ankle throbbed with every step. He had not eaten in eighteen hours.

On day two, Carr found a stream and drank ice-cold water. He spotted a German patrol 200 yards away and lay motionless in a ditch for two hours as they passed.

By day three, hunger was overwhelming. Carr was burning 4,000 calories a day just to stay warm and had consumed none. His body began cannibalizing muscle tissue for energy. He decided that, if he survived until morning, he would surrender. The Luftwaffe, he reasoned, treated captured pilots better than the Wehrmacht or the SS. Aviators respected fellow flyers, even enemy ones. POW camps were described as boring but survivable, with three meals a day, Red Cross packages, and letters from home.

The Opportunity: A Lone Fw 190

On the fourth day, late afternoon, Carr reached the edge of the German airfield. He positioned himself in a treeline overlooking the eastern perimeter. Through the branches, he saw hangars, fuel trucks, and aircraft—mostly Fw 190s, a few Bf 109s. He planned to wait until morning, then walk to the main gate with his hands up.

As darkness fell, Carr noticed something: a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 sat in a revetment just eighty yards from his position, partially concealed by camouflage netting. Two mechanics worked under portable lights, checking fuel and running the engine through a preflight inspection. When they finished, they shut down the engine, covered the cockpit, and walked back toward the hangars. The Fw 190 was ready to fly.

Carr’s mind began to calculate. He had never flown a German aircraft, did not speak German, and had no idea where the controls were or how the engine started. But he knew how to fly, with over 500 combat hours. Every aircraft has a throttle, a stick, and rudder pedals. The physics do not change because the labels are in German. Carr was looking at a fully fueled fighter with no guard. The plan to surrender evaporated.

The Theft: Into the Cockpit

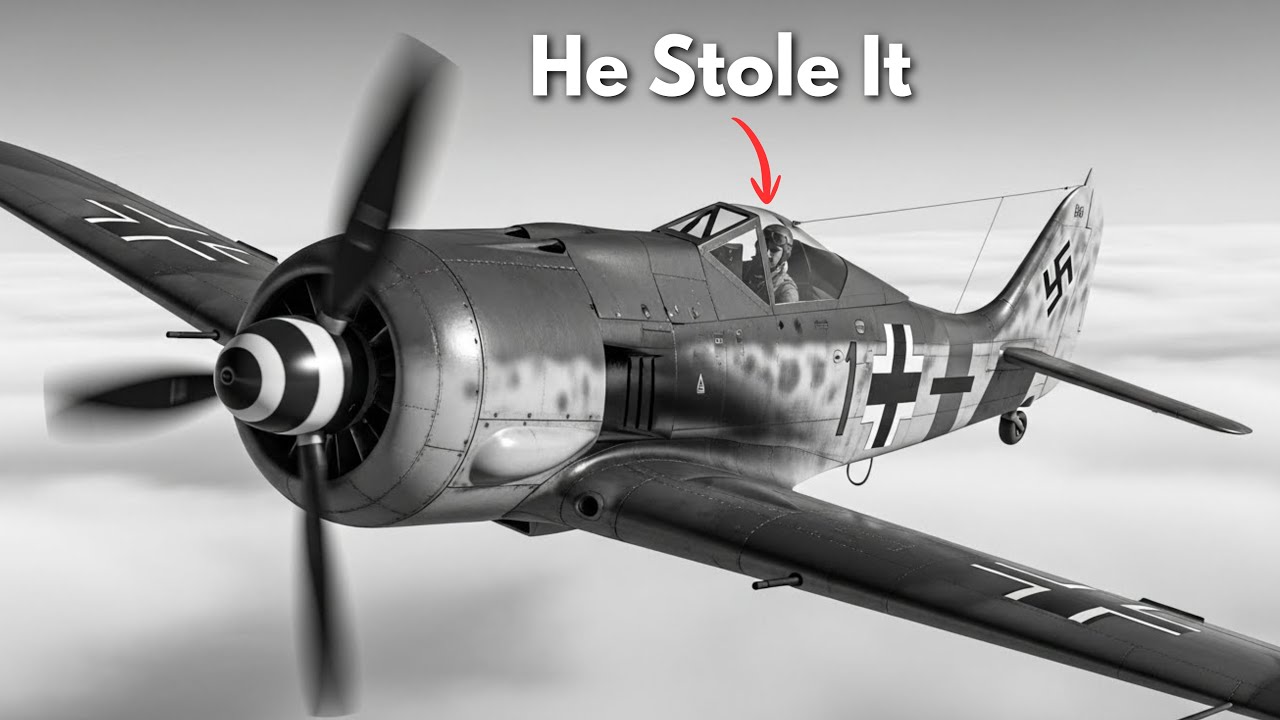

At 3:00 a.m., the airfield was quiet. Carr moved—eighty yards of open ground, no cover, his twisted ankle screaming with every step. The Fw 190 was larger than expected, nearly a ton heavier than the P-51. The cockpit sat high, protected by 30mm armored glass. The BMW 801 engine dominated the nose—a 14-cylinder air-cooled radial producing 1,700 horsepower. The Fw 190, known as the “Butcher Bird,” was Germany’s premier fighter.

Carr climbed onto the wing. The canopy was unlocked. He slid it back and dropped into the cockpit. He could not read anything—every label and gauge was in German, the instrument panel a wall of incomprehensible Gothic script. The cockpit was smaller than the P-51’s; Carr’s knees pressed against the instrument panel. The control stick fell naturally to his right hand, the throttle to his left. Some things, at least, were universal.

With four hours until sunrise, Carr used every minute to trace wiring, identify gauges by their position, and locate critical controls. He found the fuel selector, magneto switches, propeller control, and eventually, a T-shaped handle with German text that looked vaguely like “starter.” He pulled it—nothing happened. He pushed it—a mechanical whine filled the cockpit as the inertia starter wound up. After spinning for twenty seconds, Carr pulled the handle again. The BMW 801 coughed, caught, and roared to life.

The noise was apocalyptic. Every German on the airfield would hear it. Carr had seconds. He shoved the throttle forward. The Fw 190 lurched, tail up almost immediately. At 90 mph, Carr pulled back on the stick, and the Fw 190 leapt into the air, clearing the hangar roofs by inches.

The Escape: Flying Home in a Stolen Fighter

Carr was airborne in a stolen German fighter, 200 miles behind enemy lines. Now came the hard part. The cockpit was a nightmare of unfamiliar systems. Carr solved problems one at a time. He found the landing gear lever and retracted the gear. The aircraft accelerated. He identified the gyro compass, oriented himself west-southwest toward France and Allied lines. He climbed to 500 feet, then thought better of it. At altitude, he would be visible to German radar, fighters, and anti-aircraft batteries. He dropped to treetop level—50 feet above the ground at 280 mph.

For forty-five minutes, Carr flew west. The sun rose behind him. The terrain changed from forest to farmland to the scarred battlefields of eastern France. He crossed the front lines, and that’s when the real trouble began.

Allied anti-aircraft gunners saw what they expected: a German Fw 190 flying low toward their positions. They opened fire. Tracers arced toward Carr from every direction. He had no radio to announce himself, no way to signal that he was friendly. The Fw 190 still carried German markings—the black crosses on the wings, the swastika on the tail. Carr did the only thing he could: fly lower and faster. He dropped to twenty feet, hedge-hopping, kicking up dust from the roads below. French civilians dove into ditches as he screamed overhead. American soldiers fired rifles at him. Every gun in France seemed to be shooting at Bruce Carr.

The Fw 190 took hits. Carr could hear the impacts, feel the shudders, but the German engineering held. The aircraft kept flying.

The Landing: Home at Last

Carr recognized the airfield—A-66 at Conté, France, home of the 354th Fighter Group. He lined up for approach, no time for pattern work or radio calls. The anti-aircraft batteries were already tracking him. That’s when Carr discovered the final problem: the landing gear would not come down. He pulled the lever—nothing. He pumped it—nothing. He searched for a backup system, an emergency release, anything. The Fw 190’s landing gear operated on hydraulic pressure, directed by a selector valve. Carr did not know this and had been pulling the wrong handle.

Below, the 354th’s anti-aircraft crews loaded their 40mm Bofors guns, preparing to blow the German fighter out of the sky. Carr made a decision: he would belly land. He lined up with the grass beside the main runway, lowered the flaps, and cut the throttle. The Fw 190 sank—100 feet, 50 feet, 20 feet. The aircraft hit the grass at 90 mph, slid for 300 yards, threw up a rooster tail of mud and debris, and ground to a stop. Carr was alive.

Within seconds, the Fw 190 was surrounded by military police, rifles raised, screaming at the pilot to get out. They expected a German. Instead, a mud-splattered American in a torn flight suit climbed onto the wing. “I’m Captain Carr of this goddamn squadron.” Nobody believed him. He had been missing for four days, presumed dead or captured, and had just belly-landed a German fighter on their airfield.

Colonel George Bickel, commanding officer of the 354th Fighter Group, arrived. He looked at the destroyed Fw 190, the mud-covered pilot, the bewildered MPs. “Where in the hell have you been and what have you been doing now?”

The story spread through the Army Air Forces like wildfire—the pilot who stole a German plane, the only American in the European theater to take off in a P-51 and return in an Fw 190.

The War Continues: Ace in a Day

Carr’s war was not over. Five months later, on April 2, 1945, near Schweinfurt, Germany, First Lieutenant Carr led a flight of four P-51s on a reconnaissance mission. At 15,000 feet, he spotted a massive formation of German fighters—sixty aircraft, the largest concentration he had ever seen. Standard tactics dictated immediate evasion; four against sixty was suicide.

Carr, however, was never interested in manuals. He keyed his radio: “Engaging.” His wingmen did not hesitate; they had flown with Carr before and knew what he was capable of. The four Mustangs climbed into the German formation. The Germans, not expecting an attack, flew in a loose defensive formation, probably heading to intercept a bomber stream.

Carr slipped into the back of the formation, positioned himself behind a Bf 109, and fired. The German pilot never saw him; the 109 exploded. Carr shifted to another target—an Fw 190. Three seconds of .50 caliber fire, and the Butcher Bird rolled inverted and plummeted toward Earth. The German formation scattered, not knowing how many Americans were attacking or where the fire was coming from. Carr moved through them like a wolf through sheep, picking targets, firing, moving. Third kill, fourth kill, fifth kill. In three minutes, Carr shot down five German aircraft; his wingmen accounted for ten more. Four American pilots, fifteen German aircraft destroyed, zero American losses.

When the ammunition ran out, Carr led his flight home. The surviving Germans scattered across the countryside. On April 9, 1945, Carr was promoted to captain and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions. The citation reads:

“Completely disregarding his personal safety and the enemy’s overwhelming numerical superiority and tactical advantage of altitude, he led his element in a direct attack on the hostile force, personally destroying five enemy aircraft and damaging still another.”

Carr became the last “ace in a day” in the European theater of World War II. No American pilot would match his feat before Germany surrendered. By the end of the war, Carr had flown 172 combat missions and accumulated 14 or 15 confirmed aerial victories, plus numerous ground kills. He was 21 years old.

Beyond World War II: A Lifetime in the Air

After the war, Carr stayed in uniform. He joined the Acrojets, America’s first jet aerobatic demonstration team, flying F-80 Shooting Stars. In Korea, he flew 57 combat missions in F-86 Sabres with the 336th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, eventually commanding the squadron from 1955 to 1956. As a colonel, Carr ran a fighter squadron—the kid from Union Springs, New York, now a leader of men.

In Vietnam, Carr, now 44 years old, flew 286 combat missions in F-100 Super Sabres—close air support, bombing runs, and strafing missions. The work was the same as he had done 24 years earlier in a different war, in a different aircraft. Three wars, three generations of aircraft, 505 combat missions. Carr retired in 1973.

On April 25, 1998, Bruce Ward Carr died of prostate cancer at 74. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, section 64, grave 6922, among the heroes of every American war since the Revolution, within sight of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and across the river from the Lincoln Memorial. His headstone lists his rank, Colonel, United States Air Force, and his decorations: Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross with clusters, Air Medal with clusters, Purple Heart. It lists his wars—World War II, Korea, Vietnam—but does not mention the Fw 190, the four days in the Czechoslovakian forest, or the belly landing with no gear.

Some stories do not fit on headstones.

The Legend and the Record: Two Stories, One Man

There are two ways to tell the story of Bruce Carr. The first is the legend: the downed pilot who stole a German fighter from an active airfield, figured out the controls by trial and error, and flew 200 miles back to Allied territory while every gun in Europe shot at him. The second is the documented record: the ace with 15 kills, the Silver Star recipient, the Distinguished Service Cross winner, the man who led four aircraft against sixty and won. Both are true. Both are remarkable.

But what matters most is the character behind the story. In November 1944, Carr found himself alone, unarmed, and stranded 200 miles behind enemy lines. The rational choice was surrender. The safe choice was giving up. Carr chose differently. He looked at a German fighter covered in unfamiliar instruments and saw not an obstacle, but an opportunity. He climbed into a cockpit he had never seen, started an engine he had never operated, and flew an aircraft he had never touched before—not because he was reckless, but because he refused to accept that his options were limited to the ones that seemed possible.

Four months later, faced with sixty enemy fighters and four friendly aircraft, Carr made the same calculation. The rational choice was retreat. The safe choice was survival. He chose attack, and fifteen German pilots never made it home.

The Final Flight: A Last Testament

In 1997, a year before his death, Colonel Carr flew one last time. The Fantasy of Flight Museum in Florida invited him for an air show. Carr, now 73, arrived in a P-51D Mustang, his own aircraft maintained in flying condition. He came in over the crowd at 300 knots, 50 feet off the deck—the same approach he had used 50 years earlier, flying a stolen Fw 190 into a French airfield while his own side tried to shoot him down.

The crowd watched as a 73-year-old man threw a World War II fighter through maneuvers that would challenge pilots half his age: loops, rolls, high-G turns that pressed him into his seat at forces that would gray out younger men. When he landed, someone asked what he was thinking up there. He shrugged. “Same thing I was always thinking. What’s the airplane capable of? What am I capable of? Let’s find out.”

Conclusion: The Spirit of Bruce Carr

The story of Bruce Carr is not just about a stolen fighter, fifteen kills, or three wars and 505 combat missions. It is about a pilot who looked at impossible odds and asked, “What else can I do?” Carr’s legacy is one of relentless determination, creative problem-solving, and the refusal to accept defeat. He saw opportunity where others saw obstacles, and he acted when the rational choice was surrender or retreat.

Carr’s actions remind us that heroism is not always about following orders or playing it safe. Sometimes, it is about seeing beyond the limitations imposed by circumstance and daring to try the impossible. His story is a testament to the power of individual initiative, the value of experience, and the enduring spirit of those who refuse to give up.

In the end, Bruce Carr’s greatest achievement was not the aircraft he stole, the enemies he defeated, or the medals he earned. It was the example he set for generations of pilots and soldiers: when faced with the impossible, ask, “What else can I do?”—and then do it.