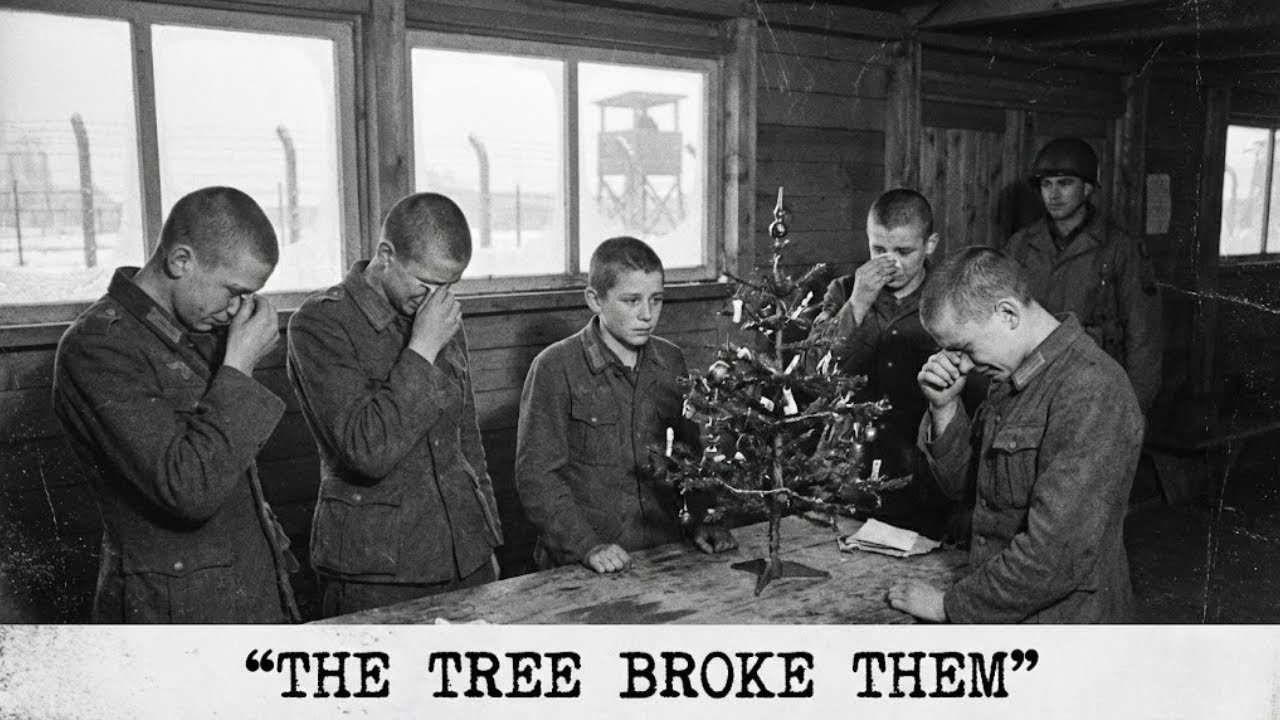

December 24th, 1944. A cold barracks compound near the Western Front. Snow packed hard under boots and tire chains. A generator coughed in the dark, then steadied into a thin metallic hum. Inside the messole, a pine tree stood upright, freshly cut, bleeding sap onto rough floorboards. Before the first hymn could form, the room changed.

Not with shouting, not with anger, with silence so heavy it felt like a blanket thrown over every mouth. The boys stared at the branches as if the tree had accused them of something. Then the smallest of them began to shake. The guards expected smiles. They expected gratitude. They expected a child’s relief. What they got was a sound no soldier forgets.

A hall full of young German soldiers breaking apart at the smell of home. And in that moment, it became clear the war had stolen something even victory could not return. The boys were not old enough to be called men in any honest country. Yet by late 1944, honesty had become a luxury. Germany’s war machine, once loud with confidence, now ran on shortages, fear, and the bodies of the very young.

The Third Reich had begun the war with trained armies and the promise of swift triumph. It was ending the war with children holding rifles. In 1944, the imbalance was visible in numbers that felt like fate. The United States produced tens of millions of tons of steel in a year. Germany produced far less under bombardment, shortages, and constant repair.

For every factory Germany lost, the Allies built more. For every tank Germany scraped together, the Allies shipped thousands across oceans. Those figures mattered on maps and in staff rooms, but they mattered most in villages where boys were pulled from school benches. They mattered in train stations where mothers tried not to cry in front of uniforms that did not fit.

They mattered at recruitment offices where the papers were stamped faster than prayers. The human anchor in this story was a boy named Matias. He was 16, raised in a small town where winter meant church bells and woods. His hands were used to pencils and chores, not metal triggers. His war began, like so many, not with a battle, but with a letter.

It arrived with official language and borrowed certainty. It said the nation needed him. It said sacrifice was honor. It said the future depended on the youth. Matias read it twice, then folded it carefully because that is what children do when they are frightened. By 1944, the Hitler Youth had become more than a movement. It was a pipeline.

Boys learned marching before they learned doubt. They learned slogans before they learned history. They learned to look straight ahead even when the world around them cracked. It was not only ideology, it was desperation. Germany’s losses in the east were catastrophic. Entire armies had been swallowed by winter, Soviet counterattacks, and the grinding arithmetic of a larger enemy.

In the West, Allied bombing campaigns battered industry and rail lines. On June 6th, 1944, the invasion of Normandy opened a wound Germany could not close. By autumn, the front lines pressed inward. The Reich drew circles on maps and called them defenses, but the circles kept shrinking. Men in their 20s and 30s were already buried or missing.

Men in their 40s were already in uniform again. And then the gays turned to boys. If you’re watching right now, take a second to hit like, subscribe, and share this story with someone who needs it. And tell us where you’re listening from tonight. A city, a town, even a barracks room of your own. These stories live longer when people carry them together.

And your comment helps others find them. The folkster was the final name given to a final measure. A people’s militia. It sounded noble. It was not. It meant old men and teenagers armed with whatever could be found. It meant training shortened until it was barely training at all. It meant handing a weapon to someone and calling it preparation.

Matias’s training lasted days, not months. The rifles were older than the boys. The instructors looked tired and spoke in hard tones. They taught how to aim, how to fire, how to keep your head down. They could not teach what happens when someone screams your name in the snow. The first time Matias heard artillery, he thought the sky had torn.

The sound rolled through the ground, through his boots, into his stomach. The older soldiers did not flinch much. They had learned the rhythm. The boys did not have rhythm yet. They had only fear. The winter of 1944 came down like a lid. It brought fog and short daylight. It brought frozen fingers and weapons that jammed.

It brought the smell of damp wool and unwashed men packed close together. The war did not pause for Christmas. It rarely paused for anything. Yet the season still existed in memory. Even in a ruined Europe, Christmas meant something. For German families, the Christmas tree was not decoration. It was tradition carved into generations.

Pine scent meant warmth, candles, and songs that predated the Reich by centuries. Matias remembered the way his mother wrapped thin strings of paper around branches. He remembered apples and small wooden ornaments. He remembered his father’s careful hands lighting candles one by one. He remembered that sound of a room holding its breath before a hymn began.

Those memories were dangerous now. They made a soldier slow. They made him look backward. War demanded forward motion even into madness. But memory was stubborn. It lived under the uniform like a second skin. The camp where Matias ended up was not a prison camp in the classic sense. It was a staging and holding point near the line, a place where units were reorganized, wounded sorted, refugees passed through, and stragglers collected.

Men and boys waited there for orders that often meant death. The place smelled of coal smoke and sweat and wet leather. The commander of the camp had his own motives. Some were political, some were personal. By that late stage, officers understood morale was a thin rope. snap it and men disappeared into woods or surrendered at the first chance.

Keep it intact and they might stand in a trench one more night. So a pine tree was ordered, not a small branch, a full tree tall enough to touch the messaul rafters. It was dragged in by soldiers with numb hands, needles scattered across the floor like tiny green knives. Someone found old boxes of decorations. Some were homemade, some were salvaged.

Popcorn strings were made because there was little else. Bits of cloth became ribbons. A few candles were collected, guarded like treasure. The tree became a symbol created out of scraps. The guards expected the boys to smile. They expected a little applause. They expected gratitude that could be reported upward, a moment of civilized tradition amid the mud.

They imagined it would make the boys fight harder tomorrow. The messaul filled slowly. Boots stomped snow off at the door. Men hunched into benches. Breath floated in the air, pale and ghostlike. Light came from weak bulbs and candle stubs flickering against faces that had forgotten softness. Matias sat among boys his age and some younger, 17, 16, a few barely 14, wearing belts cinched tight to keep coats from swallowing them.

Their eyes were sharp in the way frightened eyes become sharp. They were not innocent anymore, but they were not finished becoming human either. The commander gave a short address. It spoke of duty in the fatherland. It spoke of endurance. It spoke of faith in final victory. The words hung in the air like smoke, familiar and empty.

Then the tree was revealed fully as if it had been hidden. Branches spread wide, heavy with green. The hall caught the scent. Pine sap, resin, cold forest. The smell reached into lungs and pulled hard. For a second, the boys did not move. Their faces went still as if the war had paused. Their hands tightened on mugs. Their throats worked silently.

Someone swallowed too loud. And then the first sob broke free. It did not sound like a man crying. It sounded like a child trying to be quiet and failing. A small animal sound, wounded and ashamed. Then another boy began. Then another. The sobs spread across the benches like fire catching dry grass. Matias felt it before he understood it.

His chest clenched as if the air had become too thick to breathe. The smell of pine did not feel like comfort. It felt like accusation. It felt like the last proof of a world that had existed and had been ripped away. He did not see his mother’s hands on the ornaments. He saw her alone, perhaps with no candles left.

He did not see his father steady at the table. He imagined him dead or missing or too tired to speak. The tree became a doorway to everything he could not reach. A boy near Matias covered his face with both hands and shook. Another boy stared at the tree as tears ran down without blinking. One tried to laugh, a brittle, cracked sound, then folded into sobbing.

The room became a chorus of broken restraint. The guards froze. Some had expected joy. They were met by grief so raw it seemed to strip rank from their shoulders. They stood there with rifles suddenly useless. because you cannot threaten a child back into innocence. The commander’s face tightened, then softened in a way that surprised even him.

His plan had been simple. Tradition as medicine, a tree as morale, but the pine scent had reached deeper than he imagined. It had cut through propaganda like a blade. Outside, the war continued. Somewhere in the distance, artillery thumped faintly through the snow. Trucks idled, radios crackled, men shifted in trenches. But inside the mesh hall, time was stuck on a memory of living rooms and candle light. Matias wept without dignity.

The tears came hot, then cooled on his cheeks. He tried to stop them, and that only made the sobs worse. He felt like his body had betrayed him. Yet every boy around him was also betrayed. The pine tree stood silent, indifferent, as nature always is. It had grown in a forest without politics. It had been cut down for a war it did not understand.

Now it served as an altar for grief. Some of the guards sat down, not as friends, not as brothers, simply as human beings who could no longer pretend they were separate from what they were witnessing. They leaned their backs against the wall and stared at the floor. One guard looked at his gloves and flexed his fingers.

He was not old, but war had aged him. He had been trained to see the enemy as faceless. Now he was watching boys cry over a Christmas tree. His training offered no guidance. In that hall, the lines blurred. Not the lines of ideology. Those still existed. Not the lines of armies. Those were still killing each other outside.

But the line between guard and guarded, between enforcer and child, thinned into something fragile. The tree was supposed to remind the boys what they fought for. Instead, it reminded them what they had already lost. The smell carried a thousand kitchens, a thousand songs, a thousand small moments that war had devoured.

Germany in late 1944 was a nation retreating into itself. Cities were shattered from raids. Railards were broken. Coal was scarce. Food was rationed. The front demanded everything. And the home front had little left to give. On the western front, the German high command planned one last gamble. The Arden’s offensive, later known as the Battle of the Bulge, was launched in mid December 1944.

It aimed to split Allied lines, capture Antwerp, and force a negotiated peace. It was bold on paper. It was desperate in reality. The offensive used the last reserves of fuel and armored strength. It relied on surprise and winter weather to ground Allied air power. It shoved men and machines into forests and narrow roads.

It demanded speed, but speed required gasoline, and gasoline was what Germany no longer had. In that same December, Allied industry continued to roll forward. The United States and Britain had the logistical power to feed armies across continents. They had trucks, trains, fuel, spare parts. They had the ability to replace losses quickly. Germany did not.

For the boys in the messaul, those strategic facts were distant. They did not discuss oil production or tonnage. They felt the shortages in the way bread tasted thinner. They felt it in the way ammo was counted carefully. They felt it in the way officers avoided their eyes. Matias learned the war’s truth through silence.

The older soldiers spoke less about victory now. They spoke more about surviving the night. They spoke about surrender in whispers like a forbidden prayer. They spoke about the Russians with terror that needed no propaganda. The trees sobbing episode became a secret everyone shared, but no one named. It hung over the camp like fog.

Men moved differently afterward. The boys looked older by the next morning. Their faces had hardened, not with courage, but with resignation. Snow kept falling. It muffled sound, but it did not stop killing. The front shifted daily. Units were moved, broken, reformed. Orders arrived that made no sense except as an attempt to delay collapse.

Matias was sent forward with a group of folkm and young replacements. They marched at dawn. The sky was pale and empty. The cold bit through their coats. The only warmth came from the friction of fear. They passed villages with windows blown out. They passed barns burned to shells. They passed civilian carts loaded with whatever could be saved.

People watched them with eyes that did not cheer. Those eyes were not patriotic. They were exhausted. At the line, Matias saw the difference between slogans and reality. The trenches were shallow. The dugouts were damp. Men spoke in clipped phrases. Every sound mattered. A cough could draw fire. A match flare could bring shells.

The boy next to him was named Eric, 15, with hair too light and cheeks too smooth. Eric tried to speak about home, about a dog he missed. Matias listened, then looked away, because thinking of dogs felt obscene in a place where men died. All night the wind hissed through bare branches. Snowflakes drifted into the trench like ash.

Matias held his rifle and tried to keep his fingers moving. His breath fogged the sight. He wiped it with a sleeve already stiff with ice. In the distance, artillery returned. The shells did not sound heroic. They sounded like doors being slammed by an angry god. The earth shook in pulses. Dirt sprinkled down from trench walls. Somewhere someone prayed without words.

At dawn, Allied aircraft appeared when the weather cleared. Their engines were a distant roar than a closer growl. The bombs came with a falling whistle. The ground jumped. The air filled with splinters and smoke. Matias pressed his face into mud and felt the taste of iron in his mouth. He thought of the Christmas tree again.

The pine smell had become a ghost in his memory. Now the smell was cordite and churned earth. Strategically, the German offensive began to stall. Fuel ran short. Roads clogged with traffic. Allied resistance stiffened around key towns. What had been promised as a final gamble became a slow hemorrhage. Day by day, the German lines were pushed back, their last reserves spent.

For Matias, none of this arrived as strategy. There were no arrows on maps. There was only the arithmetic of survival. When to lift your head, when to stay still, when to run. Time shrank to seconds. The war became a series of small decisions. that decided whether you lived another minute. His turning point did not come during a charge.

It came in a ruined farmhouse after a bombardment. The roof was half gone. Snow fell inside as if the building had already surrendered. In the corner lay a child’s toy, a carved wooden horse blackened by fire, but still unmistakably made for play. Matias stared at it, his throat tightened. He imagined the child who had held it, the mother who had once swept that floor.

The toy said what no speech could. This war did not only kill soldiers. Nearby, an older soldier sat slumped against the wall, bleeding slowly. His lips were blue. His breathing flickered, stopping and starting like a failing lamp. Matias watched until the soldier’s eyes drifted toward him.

There was no command in them, only something like apology, as if to say, “This was never meant for you.” Then the eyes went unfocused. In that moment, Matias understood the Reich’s promise had been a trap, not only for its enemies, but for its own children. The banners and uniforms had been decoration over a furnace, and now the furnace was consuming the last fuel it had.

Weeks later, as the front collapsed, Matias saw prisoners taken. Gray-faced men with raised hands. Allied soldiers watched them carefully, rifles ready, but without the hatred propaganda had promised. It was a different war than the one he had been taught. The climax came quietly. His unit reached a small wooded area near a road, snow covering everything as if trying to hide the land’s wounds.

Engines approached, not German ones. Deeper, steadier. Allied vehicles moved along the road. An officer whispered orders to hold fire. Matias looked at Eric. His hands shook so badly the rifle trembled. His eyes were wet. Not from cold. Matias realized Eric was about to die for an order that could no longer change anything.

He remembered the messaul, the pine tree, the sobbing, the guards sitting down, stripped of purpose. The war had already ended in that room. Everything after had been delay. Matias lowered his rifle. Not in rebellion, in exhaustion. His finger slipped from the trigger, and something inside him finally collapsed.

Later, his unit surrendered, confused, frightened. weapons dropped into snow. It did not feel heroic. It felt like stepping out of a burning house and realizing you were still alive. In captivity, Matias was fed, counted, marched. He was cold, but not hunted. It took time for his body to stop bracing for impact.

He thought often of Christmas Eve, not the speeches or decorations, but the smell of pine and the sound of boys crying like children. After the war, the world would count the dead in numbers too large to feel. But for survivors, the war lived in smaller things. A smell, a sound, snowlight, a pine branch snapping underfoot. Years later, when Matias smelled pine again, his chest would tighten, not only with grief, but with the strange mercy of that moment.

When the machinery of war stalled and a Christmas tree stood like a witness exposing the truth artillery could not, that the Reich’s last winter was fought by boys who still remembered how home was supposed to smell. Oh.