They called him the madman of the ridge because in the late 1800s when every other homesteader was busy reinforcing their roofs or digging storm sellers, this man was outside doing something that looked absolutely ridiculous to everyone who passed by. It was late autumn, the time of year when the air starts to smell like iron and the leaves turned that brittle brown that warns you of the deathly cold coming soon.

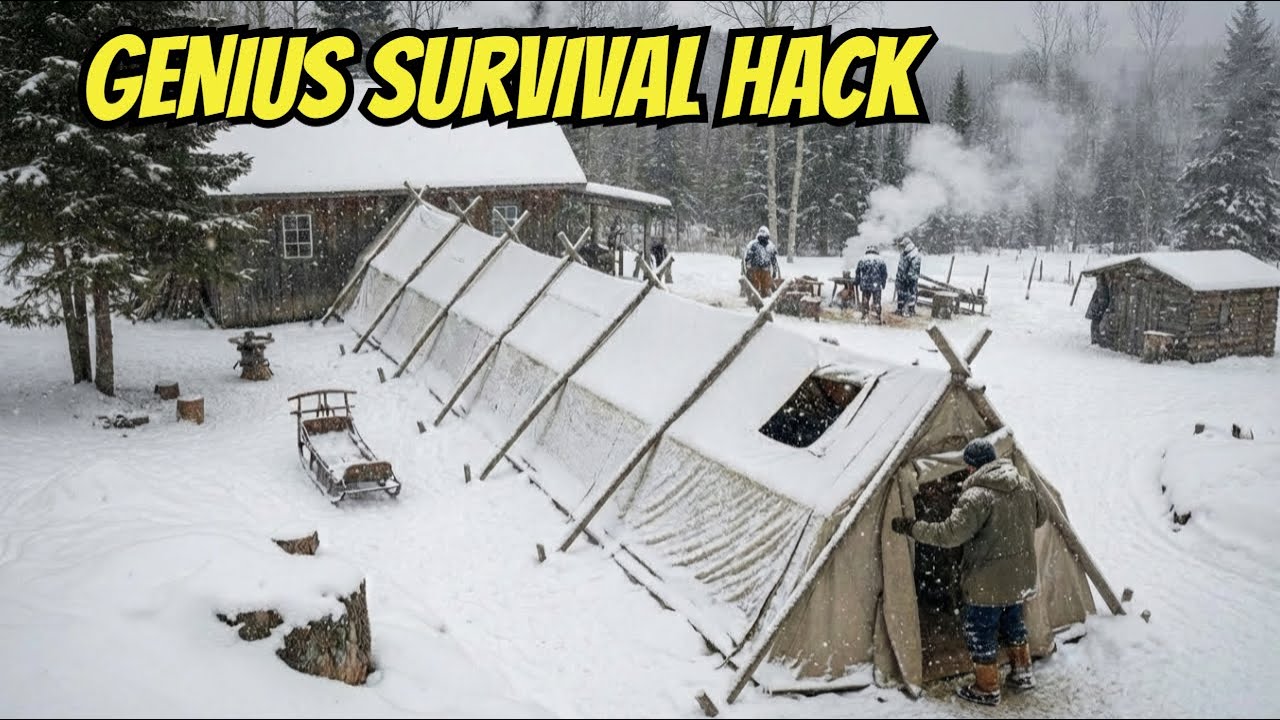

And while his neighbors were stacking their firewood against their cabin walls, just like their fathers and grandfathers had done for generations, this man was building a strange long tunnel made of scrap canvas and rough timber poles. It was unto tent for sleeping, and it certainly was unto barn for animals because it was too narrow and low to the ground stretching all the way from his woodshed directly to his front door like a giant fabric snake winding through the yard.

The people in the nearby settlement laughed at him because resources were incredibly scarce in those days and wasting good canvas and sturdy poles on a walkway seemed like the height of stupidity when you could be using those materials to patch a drafty window or cover a leaking roof. They would ride by on their horses shivering in their coats and point at the flapping structure, joking that he was building a fallway for ghosts or that he had finally lost his mind from the isolation of living so far up the mountain. But the man did unsay a word

to defend himself. He just kept tying his knots and securing the stakes into the freezing mud, ensuring that the canvas was pulled tight enough to shed water, but loose enough to breathe. He knew something that the others didn’t. Something he had perhaps learned from the indigenous tribes, or maybe figured out through years of bitter failure, which was that the biggest killer in the winter wasn’t the cold air itself, but the moisture that turned firewood into useless blocks of ice.

You see, in the frontier days, firewood was your only lifeline. It was your heat, your cooking source, and your only way to melt snow for water. So, if your wood got wet and froze, you weren’t just uncomfortable, you were dead. The neighbors thought that stacking wood against the house under the eaves was enough protection.

Believing the heat from the cabin walls would keep the logs dry. But they didn’t understand the invisible enemy that was coming for them, the man knew that when the deep snows came, the wind wouldn’t just blow over the cabin. It would swirl and eddy, driving fine powder snow into every crack and crevice of a wood pile where it would melt during the day from the sun and then refreeze at night into a solid glaze of ice that made the wood impossible to light.

His useless tunnel wasn’t just a covered walkway. It was a calculated piece of survival engineering designed to create a transition zone, a specific air gap that would save his life when the temperatures dropped to 30 below zero. As the first heavy gray clouds began to roll over the mountain peaks, blotting out the sun and turning the world into a monochrome of white and gray.

The laughter in the valley stopped because the air suddenly grew still and heavy, the kind of silence that screams of a predator approaching. The man finished the last tie down on his strange tunnel, looked at the darkening sky, and went inside his cabin, closing the door on a world that was about to freeze solid, leaving the viewer to wonder, was he a fool wasting time on a fabric toy? Or was he the only one who is actually ready for the monster storm that was about to swallow them all whole? Before we see who survives the night, hit that like button if you think

old school survival tricks are better than modern gadgets. Now, let’s see what happens when the blizzard hits. The storm didn’t just arrive. It slammed into the mountain like a freight train made of ice, burying the entire valley under 5 ft of snow in less than 48 hours. For the neighbors who had mocked the tunnel, the reality of their situation set in with terrifying speed as soon as they tried to step outside to fetch their fuel.

They opened their doors to find walls of white blocking their way. And when they finally shoveled a path to their wood piles stacked against their houses, they discovered a disaster that no amount of panic could fix. The heat escaping from their poorly insulated cabins had melted the snow resting on their wood piles during the day, and the brutal cold of the night had frozen that runoff instantly, turning their stacks of logs into solid, inseparable monoliths of ice.

Men were out there in the blinding wind, hacking away at their own fuel supplies with axes, risking frostbite and exhaustion just to pry a single log loose and even. When they managed to get a piece free, it was soaked through with frozen moisture that hissed and popped in the fire, but refused to burn hot. Inside those cabins, the temperature began to plummet because the wood they were feeding.

The stoves was spending all its energy boiling off water instead of heating the room, leading to a dangerous cycle where they had to burn more and more wood just to keep the fire from dying out completely. Children were wrapped in every blanket the family owned huddled together in the center of the room while the fathers cursed their luck and the weather, never realizing that their failure had been sealed weeks ago when they decided to trust traditional methods instead of adapting to the reality of the wind.

Meanwhile, up on the ridge, the scene was entirely different, almost peaceful in a way that would have made the struggling neighbors furious if they could have seen it. The man simply opened his front door and stepped not into the biting gale, but into the dim canvas filtered light of his tunnel.

The structure was shaking violently in the wind. Yes, and the noise of the fabric flapping was deafening, but inside the ground was dry and clear of snow. He walked in his shirt sleeves, without even needing a heavy coat, down the length of the tunnel to his woodshed, where the air was cold but perfectly dry. The genius of the tunnel was that it acted as a thermal buffer, a space that was neither inside nor outside, which prevented the drastic temperature clashes that caused condensation and icing on the wood.

The wind, which was stripping heat away from everything else in the valley, simply slid over the rounded shape of the canvas tunnel. Unable to find a flat surface to push against or a corner to drift snow into because he didn’t have to battle the elements just to get his fuel, he only burned what he needed. Conserving his energy and his supply while his neighbors were burning through their winter stores at double the rate just to try and dry out their wet logs.

He could hear the howl of the blizzard outside, a sound that usually signal a fight for life. But for him, it was just noise on the other side of a canvas wall that cost him nothing but a few days of labor to build, while others were chipping ice off their kindling with numb fingers.

He was carrying armfuls of bone dry hickory back to his stove. The wood catching fire instantly and throwing off the kind of deep penetrating heat that dries out the air and warms you to your bones. The tunnel wasn’t just a hallway. It was a time machine that allowed him to step out of the survival struggle and simply live. Proving that the most important tool in the wilderness isn’t your axe or your rifle, but your ability to see a problem before it happens.

But as the storm dragged on for weeks, a new danger emerged, one that even his tunnel might not be able to protect him from if he was uncareful. It’s easy to survive the first night, but what happens when the food runs out? Subscribe to the channel so you don’t miss the final lesson of the story.

When the spring thaw finally arrived, turning the valley from a white prison into a muddy landscape of flowing creeks and slush. The true cost of the winter became visible to everyone. The neighbors emerged from their cabins, looking gaunt and halt white, their faces gray from months of inhaling smoke from wet wood and shivering through nights where the fire offered no real comfort.

Their wood piles were wrecked halfed from the constant cycle of freezing and thawing. And many of them had been forced to burn their furniture or even the floorboards of their own homes just to make it through the final brutal weeks of February. They climbed the ridge to check on the madman, fully expecting to find a frozen corpse or a man broken by the isolation, assuming that if they had suffered so much with their conventional methods, he must have fared far worse with his ridiculous contraption, what they found stopped them dead in their tracks. The man was

sitting on his porch, shaving with a steady hand, looking as healthy and strong as he had in the autumn. His tunnel was taken down now, the canvas folded neatly away for next year. But the evidence of its success was everywhere. While the neighbors yards were mud pits, the ground where the tunnel had stood was dry and packed hard, and his remaining wood pile was pristine, the logs curing perfectly in the spring air instead of rotting in the damp.

They asked him with a mixture of shame and curiosity how he had managed to keep his house so warm that he didn’t even look tired. And he simply pointed to the pile of folded canvas. He explained that the tunnel hadn’t just kept the snow off. It had used the Earth’s own small amount of radiant heat to keep the air inside just a few degrees warmer than the outside, creating a microclimate that defied the storm.

He didn’t survive because he was stronger or tougher than them. He survived because he understood that fighting nature is a losing battle. But working around nature requires humility and imagination. The neighbors who had laughed at him were now the ones asking for his help, measuring the distance from their own doors to their sheds, planning their own tunnels for the next winter.

The story of the tent tunnel spread quietly through the mountains, not as a legend of magic, but as a practical lesson in what we now call passive design, using simple materials to control the environment without using energy. It reminds us that often the things society labels as useless or crazy are actually strokes of genius that just have you been understood yet.

Today we have central heating in Gortex jackets. So we forget that for most of human history staying dry was the only thing that mattered and a piece of canvas stretched over some poles could be the difference between seeing the spring flowers or becoming part of the frozen history of the frontier. The man on the ridge proved that the greatest survival tool is un something you can buy at a store.

It asks the willingness to look foolish to everyone else while you quietly build the thing that saves your life. So the next time you see someone doing something that makes no sense to you, do want be so quick to laugh they might just be building their tunnel while you restoill stacking wood in the rain. Would you have built the tunnel or would you have laughed with the neighbors? Let me know in the comments below.

And if you want to see more real stories of survival genius, click that video on the screen right now. It’s about a man who survived a blizzard using nothing but a candle. Thanks for watching.