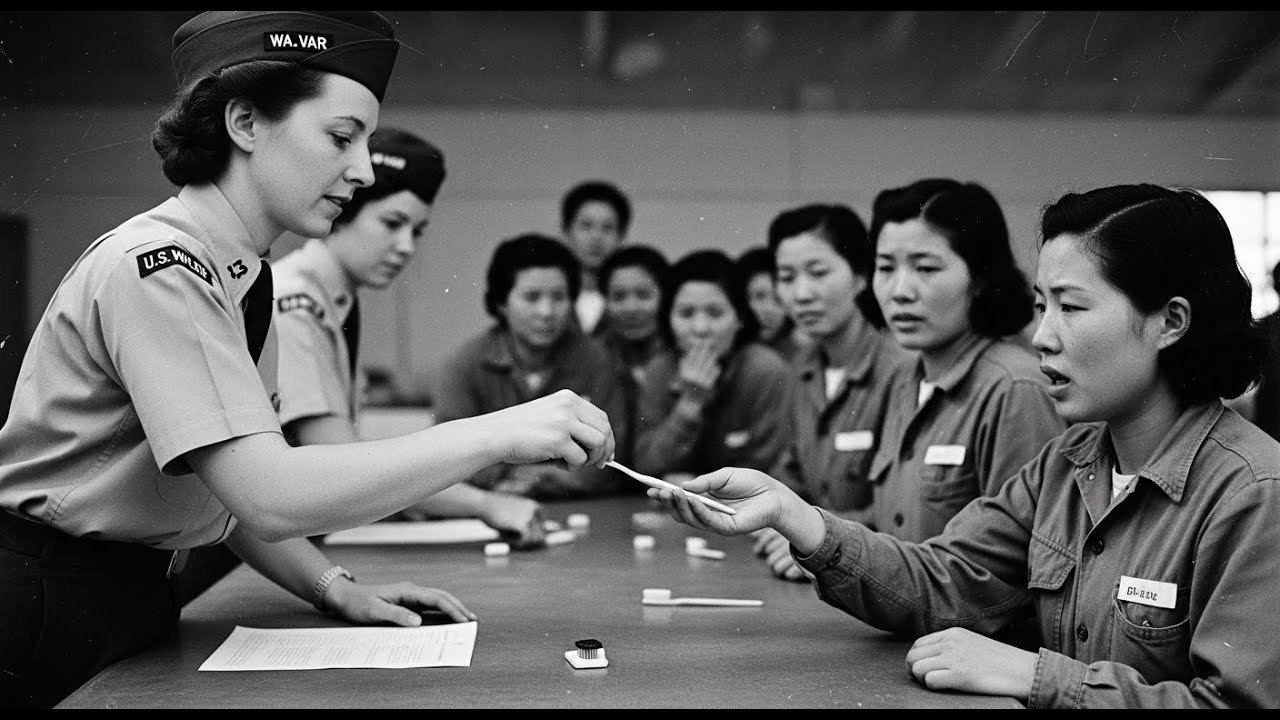

“A Brush for Every Woman” Japanese POWs Weep Over a Simple

The Toothbrush

July 14, 1945.

U.S. Naval Base, Guam.

.

.

.

The gate of the truck slammed shut with a metallic groan that seemed to echo inside Chio’s chest. Diesel fumes hung thick in the tropical air, sharp and oily, clinging to her throat. She drew Emmy closer, turning her body slightly to shield the younger nurse, whose trembling had not stopped since they were herded off the ship.

A tall Marine sergeant approached, clipboard tucked under one arm. He did not look at their faces. His eyes remained fixed on the list, names reduced to marks and numbers. He pointed toward the processing tents.

“Line up. Single file.”

Emmy flinched at the sound of his voice. Chio leaned down and whispered in Japanese, low and steady, forcing calm into each syllable.

“Don’t look. Just walk.”

As they moved forward, Chio’s eyes caught on a sign nailed to the side of the tent. The characters were Japanese, freshly painted, stark white against raw wood.

Prisoners will be treated humanely.

The word struck her like an insult. Humanely. It felt obscene, almost mocking. Barbarians did not promise humanity. Barbarians did not bother to translate lies.

Two weeks earlier, she had been certain of that.

The cave on Okinawa had smelled like rot and damp stone. The air was so heavy it felt drinkable, saturated with human waste, blood, and the faint, sickly sweetness that Chio recognized with professional dread—the early stages of gangrene.

She pressed her palm gently to Emmy’s forehead. The skin was burning hot and dry.

“Shh,” Chio whispered, her throat raw. “They will pass.”

“Water,” Emmy breathed. “Just water.”

Chio knew it was a lie. The rain had stopped days ago. The muddy pool near the cave mouth had dried into cracked earth. Outside, the world had narrowed to two sounds: the distant, rhythmic thunder of American artillery, and the immediate, terrifying crunch of boots on volcanic rock.

The boots were closer today.

They were the last two survivors of their field hospital unit. Everyone else was dead—or worse, captured. Chio’s mind replayed the images burned into her memory by Imperial pamphlets: grinning horned demons, bayonets dripping, dishonor worse than death. To be taken alive was failure. It was shame without end.

Emmy’s teeth began to chatter, a violent rattling that echoed too loudly in the dark. Chio grabbed her shoulders, holding her still.

“You must be quiet.”

Chio crawled toward the thin sliver of gray light at the cave entrance and peered through damp ferns. Two American soldiers stood thirty yards away, rifles held casually. They laughed at something, their voices deep and alien.

In her pocket, Chio felt the small cloth bag—salt. It was meant to replace what the body lost to sweat and sickness. For her, it served another purpose. Every morning she dipped a rag into it and scrubbed her gums, trying to erase the taste of decay. It burned, but it reminded her she was still human.

Emmy coughed.

The laughter stopped.

A voice followed—not shouted, but amplified, distorted, speaking broken Japanese.

“Come out. Safe. Water. Medicine.”

A trap. It had to be.

The pamphlets had warned them.

Chio looked at Emmy’s cracked lips, her shallow breathing. Emmy would die in the cave. That was certain. Fever and infection would claim her quietly, without dignity.

The voice outside repeated the word again.

“Anzen. Safe.”

Chio made her decision.

She did not die in the cave.

Neither of them did.

Instead, Emmy drank clean water from an American canteen, tilted gently by a soldier with tired blue eyes. She was lifted onto a stretcher. She was given penicillin aboard a ship that smelled of diesel and vomit and fear.

Chio had prepared herself for brutality. She had prepared herself for death.

She had not prepared herself for efficiency.

Days later, on Guam, she stood in line with hundreds of other women—soldiers, civilians, old women, children—funneled through processing tents like components on an assembly line.

They took her name.

They took her possessions.

When she placed the small cloth bag of salt on the table, the soldier swept it into a bin without a second glance. The last thread of her old life disappeared like trash.

They were given numbers.

Then came the delousing tent.

“Remove all clothing.”

This, Chio thought, was the final humiliation.

She turned her back as she undressed, a reflex of modesty that felt almost defiant. The fabric of her uniform tore as it fell away. She stood exposed, skin prickling in the humid air.

A woman in khaki trousers raised a metal canister. White powder burst across Chio’s hair, her skin, stinging her eyes. DDT. She coughed, blinking back tears.

We are insects, she thought. This is the truth behind the sign.

Then the showers started.

Hot water—astonishingly hot—poured from the pipes, cascading over her scalp, her shoulders, washing away months of filth. The heat unlocked muscles clenched in terror since Okinawa.

Chio gasped.

She heard Emmy sobbing softly beside her, not from pain, but from relief.

Hot water was not torture. It was comfort.

Soap followed. Real soap. It lathered thickly, the scent harsh but clean.

For a moment—just one—Chio forgot the war.

When it ended, they were given clothes: oversized khaki trousers and shirts, stiff but dry. Then, as they exited the tent, a woman pressed a small canvas bundle into Chio’s hands.

She opened it later, sitting on the ground beside Emmy.

Inside were three items.

Soap.

A comb.

And a toothbrush.

Brand new. Personal. Plastic.

Chio stared at it, her fingers trembling.

A toothbrush was not a weapon. It was not necessary for survival. It was maintenance. It implied a future.

Around her, women cried silently.

That night, Chio brushed her teeth for the first time in nearly a year. The mint burned sweet and clean. It tasted like a world she had been told no longer existed.

Weeks passed.

Emmy recovered. Chio worked in the camp hospital alongside American nurses. They were strict, professional, and impersonal—but not cruel. Supplies were endless. Gauze was discarded without hesitation.

When Chio tried to save a scrap, Captain Miller quietly threw it away and pressed a full tin into her hands.

“We have enough,” she said.

The words shattered something inside Chio.

This was their power—not bombs, not ships, but abundance. The ability to make humanity routine, enforced not by emotion but by policy.

When Japan surrendered, the barbed wire no longer felt like a cage. It felt like protection.

Months later, as Chio packed to return home, she held the toothbrush in her hands. The bristles were worn now, the handle scratched. It was no longer a luxury.

It was hers.

She wrapped it carefully and placed it in her bag.

Not as a souvenir.

As testimony.

She walked toward the ship with her head high, carrying the small, ordinary object that had taught her more about power—and dignity—than any weapon ever could.