German POWs Expected to Freeze to Death… American Soldiers Wrapped Them in Blankets and Fed Them

Blankets at Bastogne’s Edge

Chapter 1 — The Field of Wire (Belgium, December 1944)

The cold arrived like an enemy you could not shoot.

.

.

.

By nightfall the Ardennes forest was a black wall on the horizon, and the open field—ringed in hurried barbed wire—felt even more exposed under the pale moon. Forty-seven German soldiers sat or crouched on frozen ground, shoulders hunched, arms wrapped around their knees as if they could hold their body heat in place by force of will.

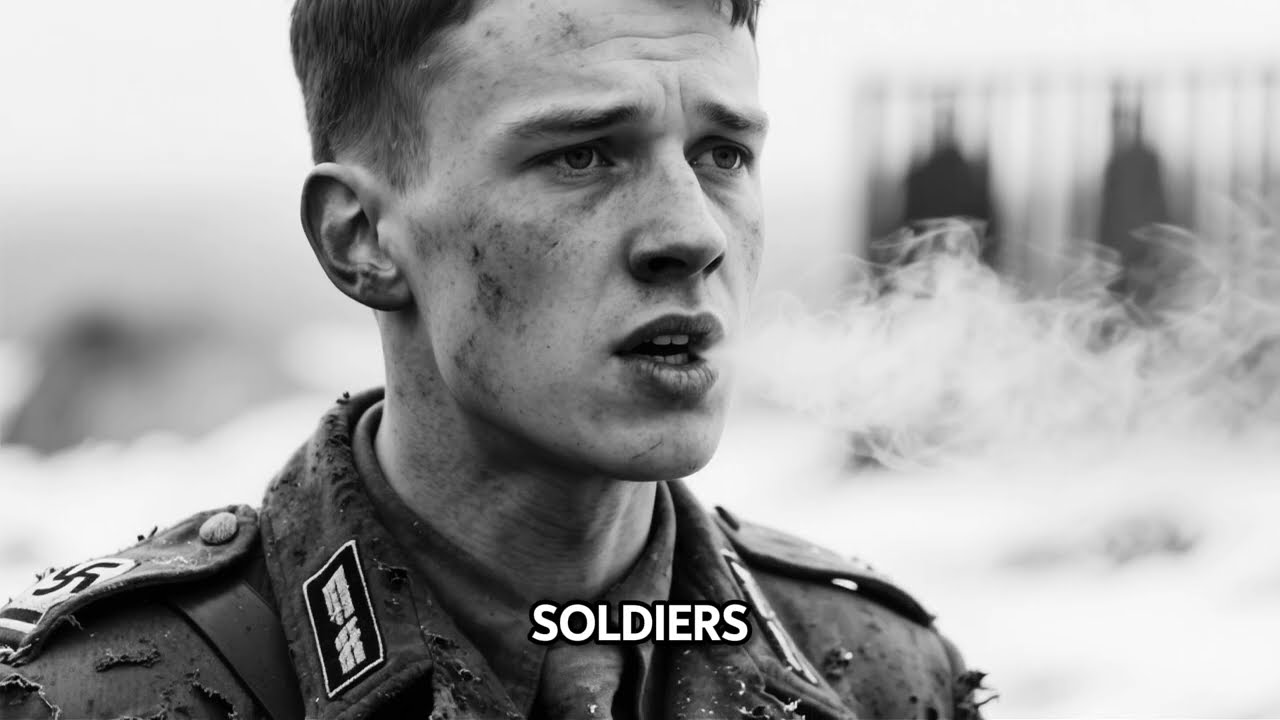

They had been captured during the first shock days of the offensive the world would later call the Battle of the Bulge. Their uniforms were wrong for the season—summer-weight cloth, torn and mud-darkened, stiff with damp. Their boots were thin. Their gloves, if they had any, were inadequate. Every breath turned to a small cloud that drifted away and disappeared, as if the air itself was stealing warmth.

Hans Krueger sat near the center of the enclosure, where the wind seemed to find him no matter how he turned. He was twenty-three, from Hamburg, conscripted when the shipyard where he worked became ruins under bombs. He had survived the Eastern Front—had learned the cruel mathematics of winter and war—but he had survived it with heavy coats and organized supply. Here, behind American lines, there was only thin cloth and open sky.

He did not ask whether they would freeze.

He asked how long it would take.

A private from Munich whispered beside him, voice thin with cold. “Until morning?”

Hans stared at his own hands and tried to remember what warm skin felt like. His fingers were already clumsy, the joints stiffening. “Some of us,” he said quietly. “Maybe not all.”

In the distance American guards paced near the fence, stamping their boots. They looked tired too, young men pulled from homes and farms and city streets, now watching enemies in the snow. The prisoners had been searched and tied roughly—efficiently, without unnecessary cruelty, but without softness either. The Americans had reason to be wary; rumors were spreading about infiltrators, stolen uniforms, sabotage. Still, none of that mattered now. The cold did not care who wore which flag.

Hans had heard what the propaganda said: that Americans were brutal, that surrender meant torture or death by neglect. Sitting in this frozen pen, he began to think the propaganda might be correct in the simplest way possible. Not by beatings, not by bullets—just by letting nature finish the job.

Around him, men fell silent one by one. Hypothermia was beginning its quiet work, turning fear into sluggishness, speech into muttering, motion into stillness. A strange calm settled over the field, the calm of people running out of options.

Hans closed his eyes and thought: So this is how it ends. Not with a battle, but with cold.

Chapter 2 — The Man Who Understood Winter

Staff Sergeant William Cooper watched from a guard position, arms folded, jaw tight.

He was thirty-one, from Wisconsin, a dairy farmer before the army. He knew cold the way some men knew engines—by instinct, by experience, by the memory of winter mornings when a mistake could kill livestock and ruin a season’s work.

From where he stood, Cooper could see what the prisoners themselves could not yet admit: their movements were slowing too fast. Their huddles were no longer the restless shifting of uncomfortable men. It was the stillness of bodies conserving the last of their warmth.

A corporal beside him shrugged helplessly. “We barely have enough blankets for our own guys, Sarge. This offensive caught everyone short.”

Cooper believed him. In the past three days, everything had been improvised—defensive lines, supply runs, rest rotations. Men were fighting, bleeding, freezing. Resources went where the fight was.

But Cooper also heard his father’s voice the way a man hears an old song—steady, plain, impossible to forget.

If it’s under your care, it’s your responsibility.

The prisoners were under American control now. That fact was simple, and to Cooper it meant something. Power did not grant permission to neglect. It created obligation.

“Find Lieutenant Morrison,” Cooper said. “Tell him the prisoners won’t make it through the night without blankets. Maybe a fire.”

The corporal hesitated, then went, disappearing into the dark where tents and command posts clustered behind the line.

Cooper kept watching. He tried to think like a soldier—resources, priorities, tactical necessity—but the farmer in him refused to turn away from a living thing dying slowly for lack of shelter. This was not sentiment. It was practicality seasoned with decency: forty-seven men freezing would become forty-seven bodies to account for, forty-seven moral stains that would outlast the battle.

When Lieutenant James Morrison finally appeared—young, exhausted, eyes rimmed with sleepless strain—Cooper spoke quickly and clearly.

“Sir, they’re going to freeze out there.”

Morrison glanced toward the enclosure and then back at Cooper, the conflict plain on his face. He was twenty-five, educated, trained in protocols and diagrams, but now living inside chaos.

“We can’t spare much,” Morrison said. “My men are cold too.”

“I understand, sir,” Cooper replied. “But if we do nothing, some of those prisoners will die. Maybe all.”

Morrison ran a hand across his forehead. For a moment he looked older than his years. Then he nodded once, the way a man nods when he chooses the harder road because it is the one he can live with.

“Fifty blankets,” he said. “From division supply. And if you can build a fire without stealing fuel from combat needs, do it. Soup if the field kitchen has surplus. But our troops get fed first.”

Cooper did not smile. He simply exhaled, as if a tightness in his chest had finally loosened.

“Yes, sir.”

Chapter 3 — Wool and Firelight (2:00 a.m.)

The jeep returned around two in the morning with blankets piled high—thick wool, heavy with the smell of storage and use. The temperature had dropped further. The field looked almost motionless now, clusters of men folded inward like broken tents.

“Open the gate,” Cooper ordered.

The guard on duty frowned. “Sarge—security—”

“I’m not releasing anyone,” Cooper said. “I’m keeping them alive.”

He and six soldiers carried armloads of blankets into the enclosure. The prisoners looked up sluggishly, suspicion mixed with the dull confusion of cold. Hands reached out like hands in a dream.

Cooper stopped in front of Hans Krueger. Hans’s lips had gone faintly blue. His eyes were open but unfocused, like a man staring through the world rather than at it.

“Here,” Cooper said, pressing a blanket into his arms. “Wrap up.”

Hans’s fingers trembled as he pulled the wool around his shoulders. The sensation of insulation—of warmth no longer leaking away in seconds—felt almost shocking. His chest tightened, not from cold now, but from disbelief.

“Thank you,” Hans managed in broken English.

Cooper nodded and moved on, blanket after blanket, until every man had one. Some shared; some layered them; some simply buried their faces in wool as if trying to inhale life back into their lungs.

Then Cooper’s men began gathering wood—fallen branches, dead limbs, anything that would burn. They built a shallow pit in the center of the enclosure, working with stiff hands. The wood was damp. The first attempt failed. The second smoked and died. The third caught with a reluctant flare, orange light leaping into the frozen darkness.

The prisoners reacted at once, drawn toward heat the way moths are drawn toward flame. They formed a cautious circle around the fire, holding hands out, palms open, as if praying to warmth.

Hans stepped close enough to feel it on his cheeks. Pain returned to his fingers, sharp and biting, but he welcomed it. Pain meant blood was moving again.

He looked at Cooper, who stood near the fire ensuring it would hold, his silhouette cut in flickering light. The American sergeant’s face was weathered, practical. Not heroic in the grand, cinematic way—just steady, competent, present.

Hans heard himself speak, softly, in German, not expecting to be understood. “Why?”

Cooper surprised him by answering in rough German, the accent heavy but the meaning unmistakable.

“Because you are men,” Cooper said. “And men should not freeze.”

For a moment, Hans could not move. Something inside him—something built from years of instruction, slogans, and fear—stalled like a machine thrown into the wrong gear.

Men should not freeze.

It was not a political speech. It was not a debate. It was simply a moral statement delivered as if it were as obvious as gravity.

An hour later Cooper returned with two thermoses of soup. He had argued with the mess sergeant, not with fancy ideals, but with practical reasoning: fed prisoners stayed healthier; sick prisoners became a burden. War respected logistics, even when it ignored mercy.

“One cup each,” Cooper ordered, gesturing. “Don’t waste it.”

The prisoners lined up with the discipline of habit. Hans received his tin cup, steam rising from it into the air. The soup was plain—vegetable beef, thick enough to feel real—but when he drank it the warmth spread through him like medicine.

Around the fire, men spoke in whispers, as if louder voices might summon the cold back.

A private named Franz Weber leaned toward Hans, eyes wide with something like distress. “I don’t understand,” he said in German. “We were told Americans would let prisoners die.”

Hans stared into the flames and felt the old beliefs shifting, not gently, but like ice cracking underfoot.

“Maybe,” he said slowly, “we were told lies.”

Chapter 4 — Morning Without Death

Dawn arrived in gray layers, the sky brightening as if reluctantly. The temperature was still brutal, but the worst of the night had passed.

Hans stood and counted heads, forcing his mind to focus.

Forty-seven.

The same number.

No one had died.

The realization struck him with unexpected force. In war, survival often felt random, as if fate flipped coins. But this had not been random. This had been chosen. Someone had looked at forty-seven freezing enemies and decided they would not be allowed to die.

Breakfast came—more soup, hard bread, bitter coffee. The coffee was terrible, burnt and weak, but it was hot. Hot was enough.

Cooper walked the line, scanning faces, checking hands for frostbite. When he stopped in front of Hans, his questions were simple, practical.

“You okay?” Cooper asked in broken German.

“Yes,” Hans answered, meaning it. “Thank you.”

“Trucks this afternoon,” Cooper said. “You go to proper camp. Shelter. Regular food.”

Hans hesitated, then asked what he could not keep inside any longer. “Why did you help us?”

Cooper was silent for a moment. Then he answered in English, slow enough that Hans could understand most of it.

“Because it was the right thing,” he said. “Because you’re prisoners, not animals. And because letting you freeze would’ve been wrong.”

He paused, eyes narrowing slightly as if he were choosing words for himself as much as for the German standing in front of him.

“My father said: how you treat people when you have power over them shows what kind of person you are. I want to be the kind of man who gives blankets to freezing men—even if they were shooting at me yesterday.”

Hans lowered his gaze, not in submission, but in something close to respect. He had been raised on a different definition of strength—strength as domination, as hardness, as taking. Here was another kind: strength as restraint, as duty, as refusing to become what the war tried to make you.

“Your father,” Hans said quietly, “was wise.”

Cooper’s mouth twitched into a small, tired smile. “He died two years ago,” he said. “Heart gave out. Milking cows.” The smile faded into something gentler. “But yeah. He was wise.”

That afternoon the trucks arrived—canvas-covered, wooden benches, engines coughing in the cold. The prisoners climbed aboard, still wrapped in their wool blankets. The Americans did not demand the blankets back.

Hans sat beside Franz as the truck jolted forward, rattling west toward a camp that was not improvised wire but real barracks and stoves. The ride was miserable, every bump punching up through the bench, but misery had changed shape. It was no longer the misery of dying. It was the misery of living.

“What do you think happens now?” Franz asked.

Hans stared at the moving canvas, listening to the engine, thinking of the firelight in the prisoner field. “Interrogation,” he said. “Then a camp. Then… time.” He hesitated. “We may be prisoners for a long while.”

Franz nodded slowly. “Germany is losing.”

No one argued. Even speaking it felt like stepping into forbidden territory. But the night in the field had done something to them. It had made propaganda feel weaker than wool.

Chapter 5 — The Notebook Under the Pillow (1945)

The proper camp had barracks and heat and procedures. Hans was issued a winter coat that fit poorly, boots that were too large, gloves that made his fingers clumsy but warm. He ate meals that were plain but steady. He worked when assigned. He learned enough English to understand commands, then enough to understand jokes.

At night, he wrote.

He had kept a small notebook through capture—how, he could not have explained. Perhaps no one had searched well enough. Perhaps an American soldier had seen it and decided a notebook was not a weapon. In any case, it remained, and Hans filled it with words as if words could keep him from losing himself.

December 20th, 1944, he wrote. We should have died. The cold should have taken us. But American soldiers gave blankets, built a fire, brought soup. They kept us alive when letting us die would have been easier. I do not understand it, and yet I cannot forget it.

As the war ended and Germany surrendered, his letters home became more daring—not in military content, but in thought. He could not say everything; censorship cut and blacked out. Yet ideas slipped through: gratitude, confusion, questions.

In July 1945 he wrote to his younger brother, Otto, who had survived the final collapse.

He told the story again—forty-seven men, an open field, 12 degrees Fahrenheit, the certainty of death. He described Cooper’s words, the father’s lesson, the decision to treat enemies as human beings. Then he wrote something that would have gotten him reported in another setting, another time:

If we were lied to about Americans, what else were we lied to about? About the war. About our leaders. About what strength means.

Hans did not claim Americans were perfect. He had seen tired guards snap, seen fear harden faces, seen the strain of battle. But he had also seen something else: a disciplined decency that held even when it would have been easier to let go. In his mind, that was not weakness. It was a kind of moral endurance.

When he eventually was transferred—first through Europe, later across the Atlantic to a camp in upstate New York—the memory traveled with him. It became a private measure he used to judge the world: not by slogans, but by how people acted when they held power.

Chapter 6 — What Warmth Leaves Behind

Cooper went home in 1946, back to Wisconsin and the familiar stubborn work of a farm. He did not tell stories loudly. He did not decorate his actions with grand titles. But his family remembered that he kept a small list of names—German names—written carefully in a notebook tucked with his discharge papers.

His daughter once asked why.

His widow answered simply: “He said they would have died if he followed routine. He said helping them was the most important decision he made over there. He wanted to remember they were people.”

Hans returned to Hamburg after captivity into a country of rubble and silence, where everyone had losses and no one had clean hands. He became a teacher. He taught history to children born after the war—children who needed truth more than pride.

And sometimes, when his students asked what “civilization” meant, he did not begin with parliaments or treaties. He began with a frozen Belgian field.

He told them about the wire and the cold. About forty-seven men who expected to die. About an American sergeant who understood winter and responsibility. About blankets that were not strategically necessary and therefore revealed something deeper than strategy.

“The blankets saved our bodies,” he told them. “But they also did something more dangerous. They forced us to admit that propaganda can be weaker than a simple act of decency.”

He did not teach his students to worship America. He taught them to recognize the difference between power that humiliates and power that protects, between efficiency that excuses cruelty and principle that restrains it.

He told them that in war, the world tries to make enemies into objects. But sometimes, a single choice—one small, stubborn choice—pulls people back from the edge.

Forty-seven blankets. One fire. Two thermoses of soup.

The war’s great battles would fill history books. But Hans had learned that a civilization is often measured in quieter ways: by what a tired soldier does at two in the morning when no one is watching, when mercy costs something, when the simplest path is to look away.

That night in Belgium, an American sergeant chose not to look away.

And because he did, forty-seven men lived long enough to question what they had been taught—long enough to return home and rebuild, carrying with them a memory of warmth that did not belong to victory, but to humanity.