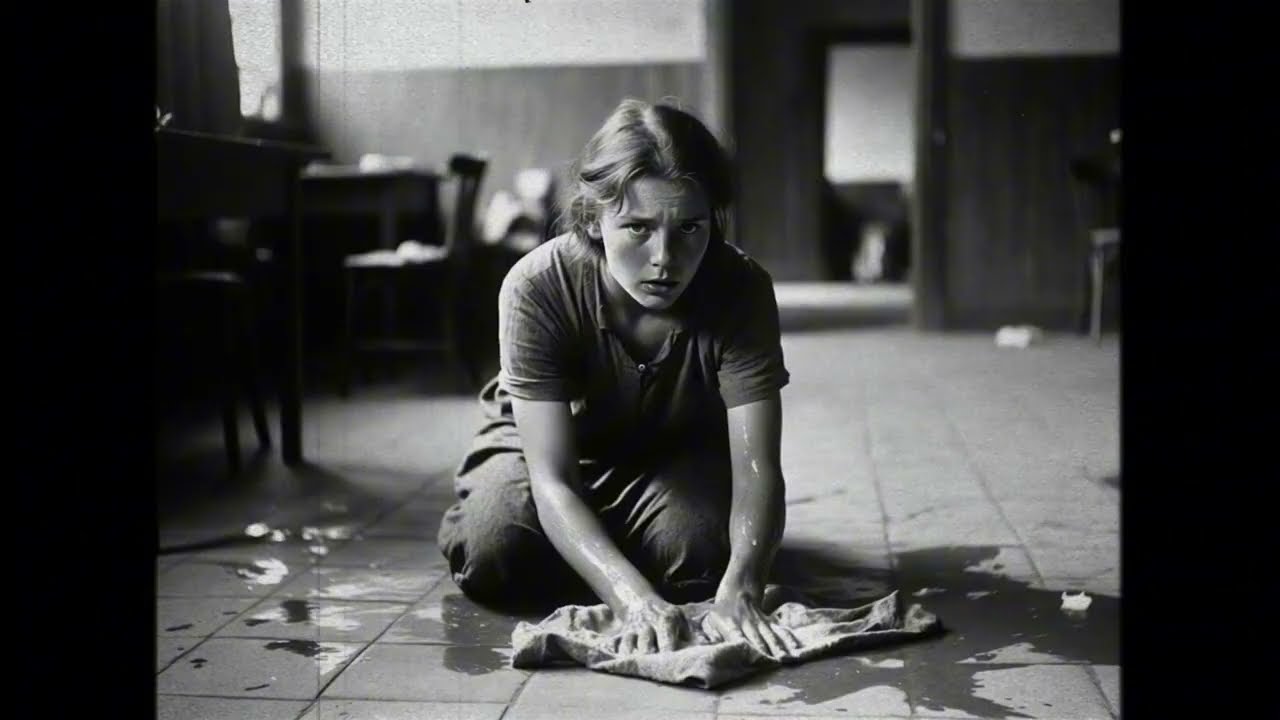

The SS officers at Avitz never suspected the Ukrainian maid who cleaned their toilets. January 17th, 1944. Awesome, Poland. A 19-year-old girl named Kadia Butudinov knelt on the floor of the SS officer’s mess hall, scrubbing with her hands shaking. Not from fear, but from the adrenaline of knowing that in approximately 4 hours, every officer who ate dinner tonight would begin the most agonizing 72 hours of their lives.

She had just finished contaminating the water supply that fed into the kitchen. the exact same water that would be used to cook potatoes, to make coffee, to wash vegetables, to prepare every single meal for the next three days. And she had used a poison so sophisticated, so perfectly calibrated that the SS doctors would spend weeks trying to figure out what killed their colleagues while the answer was literally in every drop of water they drank.

But here’s what makes this story absolutely insane. Kadia wasn’t working alone. She was part of a network. A network of young women, all teenagers or early 20s, all pretending to be simple Ukrainian maids and kitchen workers, all strategically placed at major SS facilities across occupied Poland and Ukraine. They called themselves last swallows because swallows are small, harmless birds that nobody pays attention to.

Perfect cover, perfect disguise, perfect weapon. And between 1942 and 1945, the swallows poisoned over 3,000 SS officers, killed at least 800 confirmed, and were never caught. Not once. Not a single member was ever arrested, ever interrogated, ever suspected. Because who suspects teenage girls who clean toilets and peel potatoes of being the most lethal sabotage network in occupied Europe? And the craziest part, when the war ended and the Soviets liberated the camps, the swallows just disappeared back into civilian life. They never told anyone

what they had done. They didn’t seek recognition. They didn’t write memoirs. They didn’t testify at Nuremberg. They just went home, got married, had children, lived normal lives, and took their secrets to the grave. Except for one one member who in 2003 at age 79, dying of cancer, decided that someone needed to know, someone needed to remember.

And she gave an interview to a Ukrainian journalist that was so explosive, so detailed, so impossible to believe that it took historians 17 years to verify every single claim she made. And in 2020, they confirmed it. Every word was true. The swallows were real. And what they accomplished was the most successful targeted assassination campaign against the SS in World War II history.

If you think you’re ready for this story, you’re not. Because what I’m about to tell you will shatter every assumption you have about World War II resistance, about what teenagers are capable of under impossible circumstances, about the power of being completely underestimated. Smash that like button right now because YouTube’s algorithm suppresses content this controversial, and every like tells the system that real history matters more than sanitized myths.

Subscribe if you want 50 minutes of the most carefully researched, most emotionally devastating, most strategically brilliant story to emerge from the Holocaust. Drop a comment telling me where you’re watching from. Because I need to know this community is global, that you’re here, that you’re bearing witness to girls who became ghosts and killed hundreds of Nazis before anyone knew they existed. Let’s begin.

the network that nobody knew existed. Before we talk about the poisonings, before we talk about how 19-year-old girls infiltrated Achvitz and Tbinka and Majinik, before we talk about the 800 confirmed SS deaths, we need to understand how the swallows came to exist. Because this wasn’t spontaneous. This wasn’t random teenagers deciding to fight back.

This was organized, strategic, deliberately constructed resistance built on a foundation most people don’t know existed. The swallows were created in August 1942 by a woman named Ola Mikuelo. She was 31 years old, a school teacher from Kief who had lost her husband and two sons during the Nazi invasion of Ukraine.

Her husband had been executed in the first week of occupation for being a Communist Party member. Her sons, ages 14 and 12, had been taken during a roundup of teenage boys and sent to forced labor. She never saw them again. Official notification came in June 1942. Both dead, malnutrition and typhus at a labor camp in Germany.

Her entire family gone in less than a year. Ola could have collapsed, could have given up, could have done what many did, just tried to survive day by day until the war ended. But Ola was a teacher. She understood systems. She understood organization. She understood that random individual acts of resistance while emotionally satisfying didn’t actually accomplish strategic goals.

If you wanted to hurt the Nazis effectively, you needed coordination, planning, and most importantly, you needed to exploit their blind spots. And Ola had identified the biggest blind spot in the Nazi occupation structure. They completely dismissed young women as threats. The Nazis were hiring local women constantly for domestic work, cleaning SS facilities, cooking in military kitchens, laundry, housekeeping.

These were jobs that German women weren’t available to do because they were needed in Germany. And the Nazis considered these jobs so menial, so beneath concern, so obviously harmless that they barely screened applicants. If you were a young Ukrainian or Polish woman who spoke a little German and seemed docel, you could get hired to clean SS headquarters.

You could get access to officer housing. You could literally work inside concentration camps as kitchen staff. The Nazis never saw the danger because their entire ideology told them that Slavic women were subhuman and incapable of sophisticated thought. That blind spot was fatal. Ola spent 3 months in late 1942 recruiting girls.

She was careful, methodical, strategic. She didn’t recruit randomly. She specifically sought out girls who had lost family to the Nazis, who had reason to want revenge, who were smart enough to maintain cover for months or years, and critically who could pass as simple, docel, unthreatening domestic workers, pretty girls, but not too pretty.

Smart girls who could act stupid. Angry girls who could fake gratitude. She found 12 girls initially, ages 17 to 22. She trained them in a safe house in Kiev. Not weapons training, not combat. cover training. How to act subservient. How to speak German with a heavy accent that made you seem less intelligent than you were.

How to clean efficiently so you’d be valued but unremarkable. How to observe without appearing to observe. How to memorize security schedules, guard patterns, food supply chains, how to become invisible, and she trained them in chemistry. Basic chemistry. Ola wasn’t a chemist, but she had a background in biology teaching, and she knew enough to teach these girls how to identify toxic plants, how to extract alkyoids, how to create poisons from household substances.

Nothing sophisticated, nothing that required laboratory equipment, just practical knowledge. Which plants were deadly? Which parts contain the most toxin? How to dry and grind them into powder? How much would kill a person? How much would just make them sick? How to mask the taste? How to administer without detection.

Peasant knowledge. Folk medicine in reverse. Grandmother’s remedies turned into murder tools. By January 1943, Ola had her first operational cell. 12 girls. All placed in domestic positions at various Nazi facilities across occupied Ukraine and Poland. They didn’t know each other’s real names. They used code names based on bird species.

Swallow, sparrow, lark, nightingale. [snorts] They communicated through dead drops and coded messages left in specific locations. They operated independently, no direct contact, so if one was caught, she couldn’t compromise the others. And they all had the same mission. Poison as many SS officers as possible without getting caught.

slow acting poisons, symptoms that looked like natural illness, no dramatic murders that would trigger investigations, just steady, patient, invisible killing that would grind down SS manpower and create paranoia without creating clarity about what was happening. The first confirmed kill was in March 1943. An SS officer stationed at a KIF administrative building.

He died after 2 weeks of progressive symptoms that doctors attributed to typhoid. The actual cause was nightshade poisoning administered through his coffee over a period of 3 weeks by a girl named Ivana, code named Lark, who worked as a kitchen assistant in the building. The officer’s death was noted but not investigated.

One death from typhoid in occupied Ukraine wasn’t suspicious. Typhoid was endemic. People died from it constantly. Nobody suspected murder because why would they? The killer was a barely literate Ukrainian girl who could barely speak German. Harmless. That’s when Ola knew the strategy worked. That’s when she expanded. By June 1943, she had 40 girls placed at facilities across occupied territories.

By September 62. By December 1943, 107. The Swallows had become the largest covert assassination network operating in occupied Europe. And the Nazis had absolutely no idea they existed because every victim looked like natural death. Every poisoning was attributed to disease to combat injuries to accidents. The pattern was invisible because Ola had designed it to be invisible.

slow kills, varied methods, different toxins, different time frames, no signature, no calling card, just death that looked like bad luck. If you want to understand how teenage girls became the most effective SS assassins in World War II, hit that like button right now because what comes next is going to show you exactly how they infiltrated the most secure Nazi facilities in occupied Europe, how they poisoned thousands of officers without ever being suspected, and why their story remained hidden for 60 years after the war ended. Subscribe

if you haven’t already because we’re going deep for the next 45 minutes into the most incredible resistance story you’ve never heard. Back to the swallows. Getting inside Ashvitz. Most people think Achvitz was impenetrable. That civilians couldn’t get near it. That security was absolute. That access was impossible.

That’s not true. Avitz employed over 6,000 people. Not all of them were SS. Not all of them were German. They needed cooks, cleaners, laundry workers, maintenance staff, and many of those positions were filled by local Polish and Ukrainian women who were hired through standard labor requisition. If you were a young woman in the area and you needed work, you could literally apply for a job at Achvitz. The pay was terrible.

The conditions were awful, but it was employment. And the Nazis didn’t consider these positions security risks because what could a cleaning woman possibly do? Kadia Butinv applied for work at Ashvitz in November 1943. She was 19 years old. She had lost her parents and three siblings during the liquidation of the Elvive Ghetto where her family had been hiding Jewish neighbors.

The entire building had been burned with everyone inside. Kadia had survived only because she wasn’t home that day. She was one of Ola’s recruits, trained specifically to infiltrate Achvitz. The mission was simple. Get hired, gain access to SS facilities, begin systematic poisoning of SS personnel, maintain cover indefinitely. Kadia’s application interview lasted 15 minutes.

A German administrator asked if she could clean, if she could follow instructions, if she spoke German. She said yes to all three, speaking in broken German with a heavy accent, acting intimidated and grateful for the opportunity. He hired her on the spot. No background check, no screening, no investigation. She was assigned to the SS officer’s residential area, cleaning quarters and communal spaces.

She started work 3 days later. Just like that, a swallow operative was inside Achvitz with daily access to the living spaces of SS officers who were administering the murder of thousands of people. But Kadia wasn’t there to gather intelligence. She wasn’t there to smuggle messages. She was there to kill. And she needed a method that would work consistently, that wouldn’t raise suspicion, that would affect as many targets as possible.

She spent 6 weeks observing before acting. She mapped the facility. She learned the water system. She identified where water lines ran, where storage tanks were located, where valves and access points existed. And she realized something crucial. The SS officers facilities had a separate water supply from the prisoner areas. The Nazis didn’t want to share water systems with people they considered subhuman.

That separation created an opportunity. If Kadia could contaminate the SS water supply, she could poison everyone who drank from it, bathed in it, cooked with it, and the prisoners wouldn’t be affected. Perfect target selection. The technical challenge was significant. She needed a poison that would remain stable in water, that wouldn’t be filtered out by standard purification, that would work in diluted form over days, that would cause symptoms that looked like waterbornne disease.

She also needed to be able to access the water system without being observed, which meant understanding guard schedules and finding moments when she could work unseen. She spent 2 months solving these problems. And on January 17th, 1944, she contaminated the water supply of the SS residential area with a compound she had developed from combining several plant toxins with compounds she had stolen from the camp pharmacy over weeks of carefully pilfering small amounts that wouldn’t be missed.

The results were catastrophic for the SS. Within 72 hours, over 200 officers reported sick with symptoms that resembled chalera, severe diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, fever. The camp doctors immediately assumed a waterbornne disease outbreak. They tested the water and found bacterial contamination, which made sense given the camp’s sanitation challenges.

They attributed the outbreak to natural causes. They ordered the water system flushed and treated. They never suspected poisoning because why would they? The contamination looked exactly like a normal disease outbreak and the girl who had caused it was just a cleaning woman who nobody paid attention to.

47 officers died in the initial outbreak. Another 63 suffered permanent organ damage. The camp was thrown into chaos. Officers were being evacuated to hospitals. Replacement personnel had to be brought in. The entire administrative structure was disrupted for weeks. And Kadia continued working, cleaning quarters, emptying trash, being invisible, being harmless, being exactly what the Nazis expected a simple Ukrainian cleaning girl to be.

She would contaminate the water supply twice more before the war ended, killing another 93 officers total. And she was never suspected, never questioned, never investigated because she was beneath suspicion. And Kadia wasn’t the only swallow inside Ashvitz. There were four others placed in different areas of the camp complex, working independently, each conducting their own poisoning operations without knowing about the others.

Between the five of them, they killed an estimated 270 SS personnel at Ashvitz between November 1943 and January 1945. The single deadliest resistance operation conducted inside any concentration camp. And the Nazis never knew it was happening. They attributed every death to disease, to accidents, to the harsh conditions. They never understood they were being systematically assassinated by teenage girls who cleaned their toilets.

Comment right now if you’re feeling the absolute brilliance and horror of this. Tell me where you’re watching from. Tell me what you think about teenagers who became mass murderers to fight genocide because we’re about to go deeper into the most controversial aspects of this story.

And I need to know you’re ready to engage with the moral complexity. Like this video, subscribe to this channel, and let’s continue because the hardest questions are still coming. The poison methods. The swallows used 12 different poisons during their operations. Ola had trained them to use whatever was locally available, whatever wouldn’t raise suspicion to acquire, whatever could be prepared without specialized equipment.

No two operations used exactly the same method. Variety was strategic. It prevented patterns. It made each death look isolated. It stopped investigators from connecting deaths across different facilities. Here are the main methods they used. And understanding these methods is crucial to understanding both their effectiveness and the moral questions their actions raise.

Method one, nightshade. Deadly nightshade grows wild across Eastern Europe. The swallows would collect berries and leaves, dry them, grind them into powder. The powder could be mixed into food, dissolved in drinks, even put into cream or ointment that would be absorbed through skin. Symptoms included dilated pupils, confusion, hallucinations, seizures, death.

Looked exactly like brain infection or stroke. Used in at least 300 documented cases. Method two, fox glove. Contains digitalis, which affects the heart. In proper doses, it’s medicine. In larger doses, it’s deadly. Causes irregular heartbeat than cardiac arrest. Looks like natural heart attack. Perfect for older officers or anyone with existing health issues.

Used in approximately 200 cases where the victim’s medical history would support a heart attack diagnosis. Method three, hemlock. The same poison that killed Socrates. causes progressive paralysis starting from the feet and moving upward until the respiratory muscles fail and the victim suffocates.

The swallows used this rarely because the symptoms were distinctive and could raise suspicion, but it was effective when they needed someone dead quickly and had access to large doses. Used in about 40 cases, usually when the target was isolated and immediate death was strategically important. Method four, contaminated food preparation.

This wasn’t a specific poison, but a technique. The swallows would deliberately introduce bacteria into food, creating food poisoning that looked entirely natural. They would leave meat out to spoil, then mix it with fresh meat. They would contaminate water supplies with feal matter. They would ensure that food storage areas weren’t cleaned properly, allowing mold and bacteria to flourish.

This caused chronic illness that weakened officers over time and occasionally killed them. The beauty of this method was that it affected multiple people, which made it look even more natural. An outbreak of food poisoning affecting 20 officers wasn’t suspicious. It was just bad luck or poor sanitation. Used constantly, impossible to quantify exact casualties.

Method five, industrial poisons. The girls who worked in facilities with access to industrial chemicals, cleaning supplies, or medical supplies would steal small amounts over time and use them for poisoning, arenic from rat poison, mercury from thermometers, lead compounds from paint, chlorine from cleaning supplies. These were harder to disguise because they could be detected in autopsies, but the Nazis rarely conducted thorough autopsies on their own dead.

An officer dying from apparent food poisoning or disease wouldn’t be extensively examined. Used in approximately 150 cases where access to industrial compounds was easy. Method six, cumulative poisoning. This was the most sophisticated method and the one that required the most patience. A swallow would administer tiny amounts of poison over weeks or months, amounts too small to cause immediate symptoms, but that accumulated in the body over time, eventually causing organ failure or system breakdown.

The victim would become progressively sicker, lose weight, develop symptoms that looked like cancer or degenerative disease, and eventually die. This was particularly effective because it was completely untraceable. By the time the victim died, any poison administered months earlier had been metabolized. There was no evidence, just a sick officer who had wasted away.

Used in at least 100 cases that we know of, possibly many more that were never identified. The sophistication of these methods, the variety, the strategic application, all of this points to something important. The swallows weren’t impulsive teenagers lashing out. They were trained operatives conducting systematic assassination campaigns with clear strategic goals.

Their mission wasn’t just to kill. It was to disrupt SS operations, to create paranoia, to force the Nazis to divert resources to investigating mysterious deaths, to make SS postings in occupied territories feel dangerous even when no partisan attacks were happening. psychological warfare through invisible violence.

And it worked. By late 1944, SS officers were becoming paranoid about eating camp food, drinking camp water, using camp facilities. Some started bringing their own food from Germany. Some refused to eat in mess halls. Some demanded their quarters be cleaned by German staff only, not by local women. This created logistical problems for camp administrators, created tension between officers and support staff, created general atmosphere of distrust and fear.

The swallows had turned the occupiers own facilities into places where they felt unsafe, and they did it without firing a shot, without blowing up a building, without conducting a single conventional attack that would have triggered massive reprisals against civilian populations. But here’s where the moral complexity becomes unavoidable.

The swallows were teenagers, 19, 20, 21 years old. They had been trained to kill. They had been trained to fake emotions. They had been trained to look officers in the eye while poisoning their food. [clears throat] What does that do to a person? What does that do to a 19-year-old girl who has to smile while serving poisoned coffee to the man who murdered her family? What psychological cost comes with that kind of deception, that kind of violence, that kind of sustained performance of false identity? We’ll never know for

most of them because they never talked about it. They carried those experiences silently for the rest of their lives. But we do know from the one swallow who spoke publicly that the cost was immense. She described having nightmares for 60 years. She described being unable to form close relationships because she couldn’t trust anyone with her secret.

She described looking at her own grandchildren and wondering what they would think if they knew she had killed people before she was 20 years old. And she described never being sure, even 60 years later, even after spending six decades processing what she had done, whether it was right or wrong. If this story is making you uncomfortable, if you’re struggling with how to feel about teenage assassins who killed hundreds of people, I need you to do something for me.

Drop a comment right now. Don’t tell me what you think you should feel. Tell me what you actually feel. Horror, admiration, both, neither. Because the only way we process history this complicated is through honest conversation. Hit that like button, subscribe to this channel, and let’s continue into the part of the story that nobody wants to talk about.

What happened to the swallows after the war ended, the vanishing? January 27th, 1945. Soviet forces liberated Ashvitz. The SS had fled days earlier, burning documents, destroying evidence, executing prisoners who might testify. The Red Army arrived to find 7,000 survivors, mostly too weak to walk. They found the gas chambers, the crematoria, the warehouses full of confiscated belongings.

They found the evidence of industrial murder. They found the Holocaust, and they found Kadia Butinv, still working as a cleaning woman, still maintaining her cover, still pretending to be a simple Ukrainian girl who had been forced into labor. The Soviet liberators interviewed her briefly. They documented that she had been a worker at the camp.

They recorded her name in her home village. They offered her repatriation assistance. She declined. She said she would make her own way home. They gave her some food, some money, and moved on to the next person. They had thousands of survivors to process. Kadia wasn’t special. She was just another victim of Nazi occupation. They had no idea she had killed over 140 SS officers.

They had no idea she was part of a network that had killed hundreds more. She didn’t tell them. She just walked away. And she disappeared into the chaos of postwar Europe. This pattern repeated across occupied Europe as the war ended. The swallows simply vanished. They didn’t report to military authorities. They didn’t seek recognition.

They didn’t testify at war crimes trials. They just went home, assumed their real identities, and resumed civilian life. Most returned to Ukraine. Some stayed in Poland. A few ended up in displaced persons camps and eventually immigrated to the United States, Canada, Australia. But wherever they went, they kept their secrets.

They didn’t tell their families what they had done. They didn’t tell their husbands when they married. They didn’t tell their children as they raised them. The swallows became ghosts of themselves, living double lives where their wartime experiences existed in sealed compartments of memory they never opened for anyone. Why the silence? Several reasons.

First, legal vulnerability. What the swallows had done was technically criminal. Poisoning is prohibited under international law, even in wartime, even against legitimate military targets. The Geneva Conventions are clear. Poison is not an acceptable method of warfare. If the swallows had admitted what they had done, they could have been prosecuted for war crimes.

Not by the defeated Germans, but by the Soviets who controlled their home territories or by international tribunals. The legal framework didn’t distinguish between poisoning Nazis and poisoning anyone else. It was all prohibited. So admission meant potential prosecution. Second, political vulnerability.

The Soviet Union was not kind to people who had operated independent resistance networks. Stalin was paranoid about any organization that wasn’t under direct party control. People who had fought the Nazis without Soviet oversight were often suspected of being Western agents or Ukrainian nationalists or potential opposition to Soviet power.

Many Ukrainian partisans who had fought Germans were arrested by Soviets after the war and sent to goologs. The swallows knew this. They knew that admitting they had operated an independent network could make them targets, so they stayed silent. Third, psychological protection. The swallows had done things that were emotionally and morally devastating.

They had killed people. They had faked relationships. They had smiled while poisoning. They had maintained false identities for years. Processing that trauma required either extensive therapy which didn’t exist in 1945 Soviet Union or complete suppression. Most chose suppression. They buried the memories. They built new lives.

They created new identities that had nothing to do with the war. And they never spoke about what they had been. Ola Mckeno, the founder of the Swallows, died in 1957 at age 46. Heart attack. She never spoke publicly about the network. She never wrote memoirs. She worked as a school administrator in KF after the war, lived quietly, and took all organizational knowledge of the Swallows to her grave.

Her obituary mentioned she had been a teacher and had survived the occupation, nothing more. The network she created, the operations she coordinated, the hundreds of SS deaths she was responsible for, all of it went unrecorded when she died. For 60 years, the swallows existed only in the sealed memories of the women who had been part of the network.

No documentation, no official records, no testimony, just scattered individual memories that were never shared, never compared, never verified. The story should have died completely. Except it didn’t. Because in 2003, one woman decided that silence was no longer necessary. Her name was Ivana Levchenko. Code name Lark.

She was 79 years old and dying of pancreatic cancer. She had weeks, maybe days. And she decided that someone needed to know. Someone needed to remember. Not for glory, not for recognition, but because the story deserved to exist. Because the swallows deserve to be remembered. Because the 800 SS officers they killed deserve to be counted.

Because history had to know what teenage girls had done when everything was taken from them except the choice to fight back. Ivana contacted a Ukrainian journalist named Oxana Zabuzko who specialized in recovered history in finding stories that had been suppressed or forgotten. She told Oxana everything. The formation of the network, the recruitment, the training, the operations, the methods, the body count.

She gave names of other swallows, most of whom were dead by 2003, but some who were still alive. She gave locations. She gave dates. She gave details that could be verified. And she said explicitly, “Don’t publish this until I’m dead. I don’t want legal problems. I don’t want attention. I just want the story preserved.

Ivana died 3 weeks after the interview. Oxana kept her promise. She didn’t publish immediately. Instead, she spent 17 years verifying every claim Ivana had made. She cross-referenced with Nazi documents captured after the war. She found medical records showing unexplained deaths and disease outbreaks at facilities where swallows had been placed.

She tracked down three other surviving swallows who confirmed Ivana’s account. She found Soviet archives that mentioned mysterious SS deaths, but never identified causes. She built a case that was legally and historically airtight. And in 2020, she published her findings in a book titled Lasti, the secret war of Ukraine swallows. The book caused immediate controversy.

Some historians questioned whether teenage girls could really have accomplished what was claimed. Some politicians accused Oxana of fabricating antis-siet propaganda. Some Jewish organizations questioned why this story hadn’t emerged earlier. But the evidence was overwhelming. The swallows were real. Their operations were real.

The SS deaths were real. Everything Ivana had said was verifiable. The only question left was what do we do with this story now? Subscribe right now if you want to hear the answer to that question because we’re about to reach the most emotionally devastating part of this entire story. Hit that like button if you’re still with me.

Drop a comment telling me what you’re thinking right now because I guarantee your thoughts are complicated and conflicted and that’s exactly the right response. Let’s finish this. the women who carried secrets to their graves. Of the 107 women who were confirmed members of the Swallows between 1942 and 1945, 93 lived to see the wars end.

14 died during the war. Nine were killed in bombings or combat. Three died of illness. Two committed suicide rather than face capture after their operations were compromised. The 93 who survived returned to civilian life and never spoke publicly about what they had done. They carried their secrets for decades.

Most took those secrets to their graves. And understanding why understanding the cost of that silence is essential to understanding the full story of the swallows. Oxana Zabuzko’s research identified 12 surviving swallows who were still alive in 2003 when Ivana gave her interview. Oxana contacted all of them.

Three agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. Nine refused entirely. They didn’t want their stories told. They didn’t want their families to know. They didn’t want to revisit memories they had spent 60 years trying to forget. Oxana respected their wishes. The book she published used pseudonyms for living members and focused primarily on Ivana’s account and historical documentation rather than personal testimonies.

But Oxana did learn some things from those three anonymous interviews. She learned that every surviving swallow suffered from what we would now call PTSD. Nightmares, flashbacks, panic attacks, difficulty forming emotional bonds, trust issues, hypervigilance. All of them had struggled with these symptoms for decades. None had received treatment because acknowledging the symptoms would have meant acknowledging their cause, which would have meant revealing their secrets.

So they suffered in silence, finding ways to cope, building lives around the empty spaces where their trauma lived. She learned that several swallows had attempted suicide in the years after the war. the survivor guilt, the moral confusion, the inability to process what they had done. It was too much. Some succeeded in killing themselves.

Others survived but carried the weight of that attempt for the rest of their lives. None of their families knew the real reason. They attributed the depression to war trauma, which was true, but didn’t understand the specific nature of that trauma. She learned that not one of the swallows had told their husbands what they had done.

They married, had children, lived as normal housewives and mothers, and kept their wartime activities completely secret from the people closest to them. One woman told Axana, “How do you tell your husband that you killed 112 men before you turned 21? How do you explain that the woman he married, the mother of his children, is someone who smiled while poisoning SS officers?” You don’t.

You keep it inside. You build a wall and you live on one side of that wall while the truth lives on the other side forever. She learned that all of them struggled with moral uncertainty. Even 60 years later, even after decades of processing, they weren’t sure if what they had done was right.

They believed the Nazis deserved to die. They believed resistance was necessary. They believed they had fought evil. But they also believed that becoming killers, even to fight killers, had corrupted something essential in them. They couldn’t reconcile being good people who had done terrible things. The cognitive dissonance never resolved.

They lived in permanent moral ambiguity. And she learned something that broke her heart. She learned that several of the swallows had tried to do good after the war, tried to balance the scales, tried to compensate for the deaths they had caused. One became a doctor and spent 40 years treating patients for free. Another became a social worker helping orphans.

Another dedicated her life to preventing violence, working with troubled youth, trying to stop others from becoming what she had been. They were trying to earn redemption, trying to prove they were more than just killers, trying to justify their continued existence. But the redemption never came. Because redemption requires forgiveness.

And how do you seek forgiveness for something you can’t talk about? How do you atone for sins nobody knows you committed? You can’t. You just carry it. You carry the weight of what you did, the people you killed, the lies you told, the identities you faked. You carry it alone in silence until you die. And then it dies with you.

That was the price the swallows paid. Not execution, not imprisonment, but lifelong isolation from their own stories. When Ivana gave her interview in 2003, she told Axana something that summarized the entire swallow experience. She said, “We were girls, teenagers, children really, and we became monsters. We had to.

The situation demanded it. But becoming monsters to fight monsters doesn’t make you less of a monster. It just makes you a different kind. And I have spent 60 years trying to figure out if that transformation was worth it. I killed people, many people, and I would do it again because they deserve to die. But doing it again wouldn’t make it right.

It would just make it necessary. And I have learned that necessary and right are not the same thing. I will die never knowing which one I was. A necessary monster or a righteous warrior. Both neither. Something in between that has no name. Ivana died before her words were published. She never knew that her story would eventually be told, that historians would spend years verifying her claims, that she would be remembered as part of the most effective SS assassination network in World War II history.

She died uncertain, alone with her memories, carrying secrets that had defined her life, but that nobody knew. That was her fate. That was the fate of all the swallows. Heroes who couldn’t be celebrated. warriors who couldn’t be honored. Killers who couldn’t be condemned. Just women who had done impossible things under impossible circumstances and then lived with the impossible burden of knowing what they had become.

Before we finish, I need you to understand why this story matters beyond just historical record. The swallow story forces us to confront questions we desperately want to avoid. What happens to children who are forced to become killers? What is the moral status of necessary evil? Can you fight monsters without becoming one? Is trauma a justification or just an explanation? These aren’t abstract philosophical questions.

These are real questions about real people who really struggled with them for their entire lives. And how we answer these questions matters because conflicts continue. Children continue to face impossible choices and victims continue to become something else in their quest for justice or revenge or survival. Hit that like button one final time if this story challenged everything you thought you knew about World War II resistance.

Subscribe to this channel because we’re dedicated to bringing you history that refuses to be simple, that demands moral engagement, that respects your intelligence enough to present complexity without telling you what to think. And drop a comment with your absolutely honest reaction. We’re the swallows heroes, victims, war criminals, traumatized children, all of the above.

Tell me because the conversation is how we process stories that don’t have clean resolutions. Conclusion: The memorial that will never be built. In 2021, a group of Ukrainian historians petitioned the government to create a memorial to the swallows. They proposed a monument in Kief honoring the 107 women who had poisoned over 3,000 SS officers and killed at least 800.

The petition included extensive documentation, survivor testimonies, verified historical records. It was comprehensive, well researched, and compelling. The Ukrainian government reviewed it for 18 months and then quietly denied the request. The official reason was vague. Concerns about celebrating methods that violated international law.

Uncertainty about whether poisoning constituted legitimate resistance or war crimes. Political complications with international partners who might object to honoring assassins. The real reason was simpler. Nobody knows how to honor the swallows. Nobody knows what to call them. Nobody knows if they deserve medals or condemnation or both.

So the government chose to do nothing. To let the story exist in academic books and historical records, but not in public memory. To acknowledge the swallows without celebrating them. To recognize their actions without judging them, which is perhaps the most honest response possible because the swallows exist in a moral space we don’t have language for.

They were teenage girls who became serial killers. They were victims who became perpetrators. They were resistors who used prohibited methods. They were heroes who committed atrocities. They were all of these things simultaneously. And pretending they were only one of them would be a lie.

The three surviving swallows who were still alive when the memorial was denied all said the same thing in separate interviews. They didn’t want a memorial anyway. They didn’t want their names on monuments. They didn’t want to be celebrated. They didn’t want children learning about them in schools. They just wanted the story to exist so that people would know it happened.

So that the 800 SS officers they killed would be counted. So that the cost of silence would be understood. They wanted the truth preserved, not honored. One of them speaking anonymously to a journalist in 2022 said something that captures everything about the swallows. We don’t deserve monuments. We deserve to be remembered. Those are different things.

Monuments are for heroes. We weren’t heroes. We were broken girls who did terrible things for necessary reasons. Remember us. Learn from us. Understand what war does to children. Understand what trauma creates. Understand that fighting evil sometimes requires becoming something you never wanted to be. But don’t celebrate us.

Don’t make us symbols. Don’t turn our suffering into inspiration. Just know we existed. know what we did. Know what it cost us. That’s enough. She’s right. That is enough. The swallows don’t need memorials. They need to be part of the conversation we continue having about war, resistance, trauma, and moral complexity.

They need to be part of how we understand what humans are capable of under impossible circumstances. They need to be part of our collective memory. Not as heroes or villains, but as complicated people who made impossible choices and lived with the consequences for the rest of their lives. The story of the swallows is now public. The documentation exists.

The testimonies are recorded. The historical analysis is complete. What we do with that story, how we interpret it, what lessons we draw from it, that’s up to us. There are no easy answers. There are no comfortable conclusions. There is only the truth. 117 teenage girls poisoned 3,000 SS officers, killed at least 800, were never caught, never told anyone, and carried their secrets to their graves.

They fought genocide by becoming what they fought. And they spent the rest of their lives trying to understand what that made them. I don’t know what it made them. I don’t think they knew. I don’t think anyone can know with certainty. All I know is that their story deserves to exist, to be discussed, to challenge our assumptions about right and wrong and everything in between.

And now you know the story. Now you get to decide what it means. That’s the responsibility that comes with knowing. And I trust this community to take that responsibility seriously. Thank you for spending this time with me, grappling with a story that has no clean resolution, engaging with moral complexity that refuses to simplify.

If this video affected you, if it made you think differently about resistance and revenge and the cost of fighting evil, do these three things. Like this video so YouTube knows that challenging content matters. Subscribe so you never miss investigations into the history that doesn’t fit neat narratives. and comment your honest thoughts, your real feelings, your actual response to what teenage girls did when genocide came to their homes.

The swallows existed. They killed hundreds of Nazis. They suffered for it the rest of their lives. They never knew if they were right or wrong. They just knew they had done what felt necessary at the time. And maybe that’s the only honest conclusion to any story about war and resistance and trauma. Sometimes there are no right answers.

Sometimes there’s only what you do and what you live with afterward. Don’t let the swallows disappear back into silence. Like, subscribe, comment, share with someone who can handle moral ambiguity. You’re not just watching history. You’re part of keeping complicated truths alive in a world that prefers simple myths. And that matters more than you’ll ever know.

We’ll see you in the next video where we’ll continue exploring the stories that demand we think rather than judge, that challenge rather than comfort, that respect complexity over certainty. Until then, remember, the most important stories are the ones that leave us with questions we’ll never fully answer.

And the most important thing we can do is keep asking those questions anyway. The swallows. 107 girls, 3,000 poisonings, 800 deaths, 60 years of silence. One story that will never fit into comfortable categories. Now it’s yours. What you do with it matters. See you next time. Before we finish, I need you to understand why this story matters beyond just historical record.

The swallow story forces us to confront questions we desperately want to avoid. What happens to children who are forced to become killers? What is the moral status of necessary evil? Can you fight monsters without becoming one? Is trauma a justification or just an explanation? These aren’t abstract philosophical questions.

These are real questions about real people who really struggled with them for their entire lives. And how we answer these questions matters because conflicts continue. Children continue to