December 1872. The Montana territory stretched cold and unforgiving under a slate gray sky, and Henrik Bjunstat stood at the mouth of a limestone cave 3 mi west of what would someday be called Red Lodge, staring into darkness while his neighbors called him a fool. The Norwegian immigrant had spent six weeks hauling timber up a rocky hillside when perfectly good flatland sat waiting below.

And now he planned to build his homestead cabin not on the prairie like every sensible settler but inside this cave. You’ll freeze in there, said Thomas Witmore, a former army sergeant who’d survived two Dakota winters. Stone holds cold like a dead man holds grudges. Henrik just smiled, set down his axe, and kept working.

The thing about frontier wisdom is that it often looks like madness until the temperature drops to 40 below. Henrik had arrived in Montana territory in May of 1872, one of 43 Norwegian families who’d pulled resources for the westward journey. Most had claimed valley parcels near the Clark’s Fork River, Good Bottomland, for wheat and cattle.

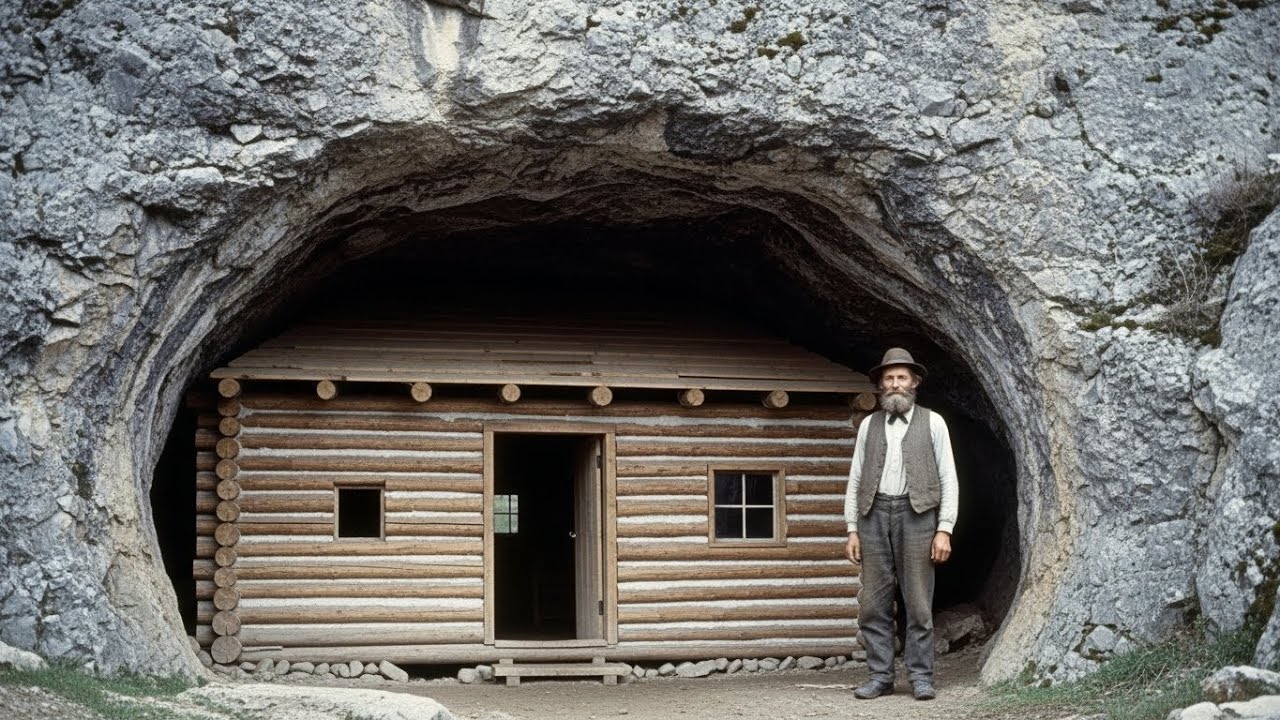

Henrik’s claim sat higher in broken country where ponderosa pine gave way to limestone outcrops and seasonal springs. His neighbors, practical men who’d already endured Montana winters, watched him pass up a decent creekside meadow to file on land that included a south-facing cave with a 30- foot wide opening and a ceiling that rose 20 ft at its highest point.

Man’s building a tomb, said James Conincaid, an Irish homesteader who’d lost three toes to frostbite his first winter. Stone don’t burn worth a dam, and you’ll need fire 6 months of the year up there. But Henrik had grown up in the Setdal Valley of Southern Norway, where his grandfather had maintained a stab, a traditional storehouse built partially into a hillside, using the earth’s constant temperature to preserve food year round.

He’d watched his father angle their family home to catch winter sun while the back wall pressed against a granite slope. Observed how the stone absorbed heat during short winter days and released it through long winter nights. The cave wasn’t a tomb. It was a tool. Through June and July, while his neighbors broke sod and planted late wheat, Henrik hauled lodgepole pine logs up the slope using a single mule named Olaf.

Each log measured 16 to 20 ft, stripped of bark, and notched with a precision that spoke of old country craftsmanship. Thomas Witmore rode up one afternoon to find Henrik constructing not a simple cabin, but an elaborate structure that would stand entirely within the cave’s mouth, using the natural stone ceiling as a roof, and the cave walls as protection on three sides.

You’re wasting timber, Thomas said, watching Henrik fit a corner joint. Could have built twice the space down on flat ground with what you’re using. Space isn’t warmth, Henrik replied in his thick accent, not looking up from his work. And warmth isn’t just fire. By August, the structure had taken shape, and neighbors began riding up out of simple curiosity.

What they found defied their experience of frontier building. Henrik had erected a log cabin measuring 18 ft wide and 24 ft deep, positioned 12 ft inside the cave’s opening. The front wall, facing south, featured two windows with real glass, precious cargo he’d protected all the way from Minnesota, positioned to capture low winter sunlight.

The rear wall stood only 8 ft from the cave’s back wall, creating a dead air space that would serve as both storage and insulation. The sidewalls didn’t quite reach the cave’s stone sides, leaving two-foot gaps that Henrik planned to fill with river rocks and clay. “It’s backwards,” declared Samuel Morrison, a Scotsman who’d built three successful homesteads across Kansas and Nebraska.

You’re trapping cold air behind the cabin and giving warm air nowhere to go. Basic thermodynamics, man. Henrik had packed the floor with 8 in of river gravel, then topped it with split pine planks that sat 4 in above the stone floor. Beneath the floorboards, he’d created an airspace that connected to the cave’s rear through carefully placed vents.

“Cold air sinks,” he explained to Samuel. “Heavy. It will flow under the floor into the back of cave and stay there. Warm air from stove will rise, hit stone ceiling, spread out. Stone holds heat, releases slow all night long. Samuel studied the floor construction, trying to find the floor in Henrik’s logic. The concept made a kind of sense.

Cold air being heavier than warm air was basic science, but applying it to frontier building seemed impractical at best. And when that cold air pool gets big enough, it’ll just flood back into your cabin, Samuel argued. You’re creating a cold reservoir right under your feet. The cave goes back 40 ft, Henrik replied, gesturing toward the darkness behind his cabin.

Maybe holds 5,000 cub feet of air. Cold air has somewhere to go always. It spreads out, stays low, doesn’t come back up unless I let it.” “And you’re betting your life on that theory?” Henrik shrugged. “My grandfather bet his life on it for 70 years. He lived, his father before him, their houses still standing in Norway, still warm. This is not theory.

This is tested knowledge.” Samuel Morrison shook his head and rode back down to the valley, convinced Henrik would be dead by February. If you’re watching this because you value the kind of practical wisdom that kept our ancestors alive in impossible conditions, consider subscribing. We’re documenting techniques that modern building codes have almost erased from memory, and your subscription helps preserve this knowledge for the next generation.

Hit that subscribe button and let’s keep this frontier wisdom alive together. September brought the finishing work. Henrik chinkedked every gap between logs with a mixture of clay, grass, and pine pitch, creating an airtight seal that would have made a ship’s corker proud. He built a stone fireplace and chimney against the cabin’s north wall.

But the design confused everyone who saw it. Instead of a simple firebox, Henrik constructed a masonry heater, a technique called a grunm in Norwegian, with interior channels that force smoke and heat through 30 ft of stone maze before venting outside. The firebox itself was small, designed to burn hot and fast rather than low and long.

“That won’t heat nothing,” said Margaret Whitmore, Thomas’s wife, who’d stopped by with bread and skepticism. “You need a big firebox for winter. Keep it burning all night. The big fire wastes wood, Henrik said, mixing another batch of clay mortar. Hot fire, short time heats the stone. Stone heats the cabin all night.

Uses half the wood, gives twice the warmth. Margaret glanced at her husband, and their shared look said everything about what they thought of Norwegian innovations. But Henrik wasn’t finished. He’d noticed that the cave maintained a remarkably stable temperature. He’d measured 54° F in the deepest section, even during summer days that topped 90.

Water didn’t freeze back there in winter. Frost never formed on the walls. The earth itself, insulated by 40 ft of limestone, held its temperature constant year round. So he dug a trench from the cabin’s floor into the cave’s rear section and installed what he called a culvert, a ventilation channel made from hollow logs that would allow him to draw the cave stable air into the cabin during extreme weather.

Thomas Witmore, who considered himself an educated man despite never finishing school, tried to explain why this wouldn’t work. You can’t pull heat from cold stone, Henrik. That’s not how temperature works. Cold air will just make your cabin colder. 54° is not cold when it’s 40 below outside, Henrik replied. Is 74° warmer than 20 below.

That’s not Thomas stopped, did the math in his head, and frowned. That’s still not how it works. October proved Henrik right about some things and seemed to prove him wrong about others. The cave cabin was indeed warmer than the valley homesteads. Interior temperatures held steady around 68° even when outdoor air dropped to 35 at night.

But it was also darker, danker, and by conventional frontier wisdom, unhealthy. You’re living in a hole, said Father Michael O’Brien, the circuit priest who served settlements within a 50-mi radius. The Lord gave us sunlight and open air for a reason. This cave dwelling seems almost pagan. Henrik, who attended services whenever Father O’Brien’s circuit brought him nearby, took no offense.

My grandfather lived to 92 in a house built against stone. My father is 76, still strong. Maybe the Lord approves of staying warm. The priest had no answer for that, though he did make a point of praying extra hard for Henrik’s soul at the next service. November brought the first real test.

A cold snap pushed temperatures down to 15 below zero for three consecutive nights, and valley homesteaders burned through firewood at alarming rates, feeding their stoves every 2 hours to keep interior temperatures above freezing. Henrik’s cave cabin, by contrast, required only two fires per day, a hot burn in the morning and another in the evening, each lasting about 90 minutes.

The masonry heater stone mass absorbed the heat and radiated it steadily for 12 hours. Interior temperature never dropped below 63°. James Concincaid rode up to see for himself, convinced the rumors were exaggerated. He found Henrik in shirt sleeves, working on a chair at a small workbench, while outside the cave mouth, frost glittered in air cold enough to freeze spit before it hit the ground.

“How much wood did you burn today?” James asked, looking around for the massive wood pile such warmth should require. “Two fires, maybe 16 of pine each time.” James did the math. He’d burned nearly 200 lb of wood the previous night alone, keeping his valley cabin barely habitable. This doesn’t make sense. You should be freezing.

Henrik walked him to the rear of the cabin and placed James’s hand on the stone wall. The limestone radiated gentle, steady warmth. “The whole cave is my stove,” Henrik said. “I just remind it to stay warm twice a day.” Word spread, but skepticism remained entrenched. Samuel Morrison, who prided himself on scientific thinking, developed an elaborate theory about how Henrik was secretly burning coal or had discovered a hot spring.

Margaret Whitmore suggested the cave was somehow heated by volcanic activity, despite Montana territory showing no active volcanism within 300 miles. The explanations grew increasingly creative because the simple truth that Henrik had understood something about thermal mass and earth sheltered building that his neighbors had never considered seemed too foreign to accept.

The alternative was admitting that generations of frontier building wisdom might be incomplete. That perhaps Norwegian immigrants who’d never seen an American winter might know something valuable about surviving cold. Pride is a powerful force. And on the frontier, admitting you were wrong about something as fundamental as shelter could feel like admitting you’d risked your family’s life on ignorance.

easier to invent elaborate explanations than face that truth. December arrived with characteristic Montana fury. A blizzard on December 8th dropped 14 in of snow and pushed temperatures to 26 below zero. Valley homesteaders huddled close to their stoves, burning precious wood reserves, while wind screamed through chinking gaps and under poorly fitted doors.

Henrik’s cave cabin registered 65° inside, requiring only his normal two fires. The cave’s mouth, facing south, remained protected from the north wind, while the stone ceiling and walls provided thermal mass equivalent to what modern engineers would call R40 insulation. By mid December, some neighbors had begun quietly asking questions.

How thick were his walls? What kind of mortar did he use? Could the same principle work without a cave? Henrik answered everything honestly, explaining that his grandfather’s generation had developed these techniques over centuries of Scandinavian winters, that thermal mass and earth sheltering weren’t magic, but simple physics applied with patience.

“So, we’re all just stupid, then?” Thomas Whitmore asked. “Pride stinging more than the cold ever could.” “No,” Henrik said carefully. You know things I don’t know. You know this land, these animals, crops that will grow here. I know stone and earth and how to hold heat. We all bring something. If you’re finding value in these stories of frontier innovation and survival, take a second to hit that like button.

It helps others discover this content and it tells us that preserving these techniques matters to you. Christmas week brought another storm, bigger than anything Montana territory had seen in 15 years. The blizzard began on December 23rd with light snow and falling temperatures. By dawn on December 24th, the wind had risen to what old-timers would later estimate at 60 mph, driving snow horizontally across the prairie in white out conditions.

temperature plummeted to 38 below zero, then 42 below. Then, according to a railroad thermometer in Billings, 40 mi north, 46 below zero. In the valley, frontier homesteads became desperate fortresses. Families burned furniture when firewood ran low. They stuffed every gap with rags, paper, and mud, huddled under every blanket they owned, and prayed the stove wouldn’t fail.

At the Whitmore cabin, Thomas kept the fire roaring while Margaret wrapped their three children in quilts and buffalo robes. The interior temperature hovered around 45° despite the massive fire consuming wood they couldn’t afford to spare. At the Kincaid place a/4 mile east, James discovered a crack in his stove pipe that was leaking carbon monoxide into the cabin.

He had to choose between freezing and poisoning his family. He chose freezing, extinguished the stove, and moved his wife and two daughters into a root cellar where earth’s insulation might keep them alive until the storm broke. Samuel Morrison’s cabin, better built than most, still couldn’t maintain livable temperature.

He burned every piece of scrap wood on the property, then started on fence posts. His wife, Catherine, developed hypothermia symptoms by the second day. confusion, slurred speech, violent shivering. Their 14-year-old son, Robert, wrapped her in blankets and held her close, while Samuel fed the dying fire and calculated how many hours they had left.

Up at the cave, Henrik was worried, but not desperate. The blizzard’s wind never reached inside the cave’s mouth. The limestone overhang deflected it upward, creating a calm pocket where snow accumulated gently rather than driving horizontally. Interior temperature, even during the storm’s worst fury, never dropped below 58°.

Henrik maintained his two fire routine, though he extended each burn by 30 minutes for psychological comfort as much as thermal need. On the storm’s third day, December 26th, something changed. The wind shifted from northwest to straight north, and its velocity increased. Snow began driving directly into the cave’s mouth for the first time, accumulating against the cabin’s front wall, piling up against the door.

Hrich watched through his window as the drift grew. 3t 4t 5 ft high. By afternoon, snow had buried the door completely and was climbing toward the windows. This was genuinely dangerous. If snow blocked the chimney, smoke would fill the cabin. If it sealed the entrance entirely, he could suffocate as oxygen depleted. Henrik grabbed a shovel and went out through the window, climbing onto the growing drift to clear the chimney.

The cold hit him like a physical blow, 44 below zero, according to his thermometer, with wind making it feel substantially worse. Exposed skin would freeze in under 2 minutes. He cleared the chimney, then dug out the door enough to crack it open, maintaining an air path to the outside. His hands achd even through heavy gloves.

His lungs burned with each breath, but the work was manageable because he could retreat back into the 60°ree cabin every few minutes, warm up, and returned to the task. Valley homesteaders, whose cabins barely maintained 40° inside, had no such luxury. Going outside meant risking death. Staying inside meant slowly freezing anyway.

Henrik had just climbed back through his window when he heard it. A sound that didn’t belong to the storm. Faint, rhythmic, almost swallowed by the wind. He stopped, listened, heard it again. Someone was chopping wood. No, someone was hitting wood repeatedly, but without rhythm. Someone was pounding on wood.

He grabbed his coat and went back outside, following the sound to its source. 50 yards down the slope, barely visible through the blowing snow, a shape moved. As Henrik fought through drifts toward it, the shape resolved into Thomas Whitmore, stumbling uphill, carrying something wrapped in blankets. Behind him, another figure, Margaret, carrying another bundle.

Behind her, a third shape that Henrik realized was their 14-year-old daughter, Emma, dragging a makeshift sled with two smaller children on it. They were abandoning their cabin. Thomas saw Henrik and shouted something lost in the wind. Henrik reached them, took the bundle from Thomas’s arms. Their youngest, a three-year-old boy named David, pale and barely conscious, and led the family up the slope to the cave.

It took 20 minutes to move 50 yards. By the time they reached the cave’s mouth, Margaret had collapsed twice, and Emma’s face showed the white patches of frostbite starting on her cheeks. Inside the cabin, the warmth hit them like a blessing. Thomas, who’d been prepared to defend his choice to reject Henrik’s help all winter, said nothing.

He just stood there while Margaret sank to the floor, still holding their middle child, a 5-year-old girl named Sarah, and wept. Our stove cracked,” Thomas finally said, his voice hollow. “Can’t run it anymore. Cabin got down to 32°. Water froze in the bucket. We were dying.” Henrik was already moving, stoking the fire, heating water, laying out blankets.

How many families still down there? Seven, maybe eight. Morrison’s place is still burning. Quincade moved to his root cellar yesterday. The Omali family, the Hendersons, the Johnson’s. Thomas trailed off, doing math that wasn’t adding up. Most will make it probably if it breaks tomorrow. But the storm didn’t break tomorrow.

It continued through December 27th, then the 28th. The wind finally died on the 29th, but temperatures remained brutally cold, 38 below on the morning of the 30th. Valley cabins had become uninhabitable. Families burned everything combustible, wore every piece of clothing they owned, and waited for the cold to kill them or the weather to break.

Henrik, meanwhile, had 11 people living in his 18x 24 ft cabin. The Whitmore had been joined by the Concades. On the 27th, James had carried his half-frozen wife up the slope after their root cellar started flooding from melting frost. On the 28th, Samuel Morrison arrived with his hypothermic wife and terrified son, having finally accepted that pride meant nothing compared to survival.

11 people in 432 square ft should have been miserable, cramped, tense, oxygen depleted. Instead, the cave cabin’s design proved itself in ways Henrik had never tested. The masonry heater, now burning three times daily instead of two, kept the interior at 66°. The cave’s natural ventilation, enhanced by Henrik’s culvert system, circulated fresh air without creating drafts.

The stone ceiling and walls absorbed moisture from breathing and cooking, preventing the condensation that plagued tightly sealed cabins. The space felt crowded but not oppressive, warm but not stuffy. Those days trapped in the cave cabin taught lessons that went beyond building techniques. The families learned to cooperate in tight quarters, to share resources without resentment, to put survival ahead of pride.

Emma Witmore taught the Morrison boy to play chess using pieces carved from kindling. Margaret and Katherine Morrison discovered they both knew folk songs from different parts of Scotland and sang together while preparing meals. JamesQade, who’d always been a solitary man, found himself telling stories about his childhood in County Cork to an audience that actually listened.

On December 30th, Thomas Whitmore stood near the fireplace, watching Henrik prepare the evening fire with the precision of a craftsman. “I called you a fool,” Thomas said quietly. “I told Margaret you’d be dead by January.” Henrik didn’t stop working. You had experience. You’d survived winters. Your thinking made sense. But I was wrong.

You were using what you knew. I was using what my grandfather knew. Different knowledge, that’s all. Henrik placed the last piece of kindling, struck a match, and watched the fire catch. Your grandfather never needed to heat a cabin through a Dakota winter. Mine did in Norway. Maybe your grandson will know something I never learned.

Samuel Morrison, listening from across the room, spoke up. That masonry heater. How long did it take your grandfather’s generation to develop that design? 300 years, maybe more. Little changes each generation. Higher channels, different stone, better proportions, not invention, refinement. And we expected to figure out Montana winters in one season.

You figured out many things, Henrik said. You grow wheat here. You raise cattle. You find water where I see only dry grass. Every man brings knowledge. The smart man learns from other men’s knowledge instead of proving his own the hard way. The storm finally broke on January 2nd, 1873. Temperatures rose to 10 above zero, practically tropical after 2 weeks of extreme cold.

Valley homesteaders emerged from their cabins to survey the damage. The Morrison cabin had a cracked ridge pole from ice accumulation. The Concincaid place had lost its entire wood pile to desperate burning. The Whitmore stove was ruined beyond repair. Across the valley, families calculated losses and wondered how they’d survive until spring.

But they had all survived, largely because one Norwegian immigrant had built his cabin in a cave and had the generosity to share it. Over the following weeks, something interesting happened. Thomas Witmore asked Henrik for detailed measurements of the masonry heater. Samuel Morrison spent three days studying the cabin’s ventilation system, taking notes on every culvert and air gap.

JamesQade brought his oldest son to learn about thermal mass and earth sheltering. By February, seven valley families had begun modifying their cabins, adding stone mass to fireplaces, insulating north walls with banked earth, experimenting with smaller, hotter fires instead of large, inefficient burns. The spring of 1873 brought new settlers to the Montana territory, and they found a community that built differently than most frontier towns.

Cabins incorporated stone mass where possible. Homesteaders chose south-facing slopes and natural windbreaks. Several families built partially into hillsides using earth’s insulation to reduce fuel consumption. The Norwegian techniques filtered through American pragmatism and local materials created a hybrid building style that would characterize the region for the next two decades.

Henrik’s cave cabin became something of a landmark. Travelers would detour to see the homestead built inside a mountain, and Henrik would give tours, explaining thermal mass and earth sheltering to audiences who no longer thought him crazy. He never lorded his vindication over those who doubted him. Thomas Whitmore and Samuel Morrison became close friends, men who’d learned that wisdom comes from many sources, and pride is a luxury frontier families can’t afford.

The 1880 census listed Henrik Bjornstad as a 46-year-old landowner with a wife, Anna, a Swedish immigrant he’d married in 1875, and three children. His property included the original cave cabin, now expanded with an above ground addition, plus a barn, a workshop, and a second stone building that served as a community meeting house during extreme weather.

His occupation was listed as farmer and stonemason, and his annual income placed him in the top third of regional earners. By 1890, the Montana territory had become a state, and the frontier was officially closed. The homesteaders who’d survived those early years were now established ranchers and farmers, and many credited their survival to lessons learned during the blizzard of December 1872.

Thomas Witmore in a letter to his brother in Ohio wrote, “We came west thinking we knew how to build and how to survive. Henrik Bjunstad taught us the difference between knowledge and wisdom. Knowledge is what you learn yourself. Wisdom is what you’re humble enough to learn from others. Modern engineers who study earthsheltered building often reference techniques that were common in 19th century Scandinavia but largely forgotten in America.

Thermal mass, passive solar design, natural ventilation. These concepts were old when Henrik used them in 1872. Developed over centuries by people who couldn’t afford to waste heat or fuel. A masonry heater like Henrik’s Grunmure can extract 85% of a fire’s heat energy compared to 15% for a typical frontier fireplace.

Earth sheltering can reduce heating costs by 60 to 70% in cold climates, exactly as Henrik demonstrated that brutal winter. The cave cabin stood for 42 years before being abandoned when Henrik’s children moved to more developed areas. The structure collapsed partially in 1924 when the cave ceiling developed a crack, but the stone fireplace and floor remained intact until the 1960s when historians from Montana State University documented the site.

They found Henrik’s design notes carved into the cave wall, measurements, temperature records, and calculations showing he’d tracked thermal performance through six winters, refining his technique each year. What’s remarkable isn’t that Henrik survived. Lots of people survived Montana winters through sheer stubbornness and burning massive amounts of wood.

What’s remarkable is that he thrived, that he did it efficiently, and that he was generous enough to share his knowledge with people who’d called him a fool. That combination of wisdom, innovation, and humility represents something essential about frontier character. Not the myth of the rugged individual, but the reality of communities learning from each other, adapting old knowledge to new challenges and surviving through cooperation rather than isolation.

If these stories of frontier wisdom and practical survival techniques resonate with you, we’d be honored to have you subscribe to this channel. We’re documenting knowledge that modern convenience has nearly erased. Techniques that kept our ancestors alive in conditions most of us can’t imagine. Your subscription helps preserve this wisdom and ensures it’s available for anyone who needs it.

Hit that subscribe button and join us in keeping frontier knowledge alive for the next generation. The lesson Henrik Bjunstad taught wasn’t really about building in caves or masonry heaters or thermal mass, though those things mattered. The lesson was about intellectual humility, the understanding that your own experience, however hard one, is only one source of knowledge, and that wisdom often comes from unexpected places.

Thomas Witmore had survived two Dakota winters and thought he knew everything about frontier building. Henrik had never seen an American winter, but understood principles that transcended geography. Both men had knowledge. Only one had the wisdom to question whether his knowledge was sufficient. That’s a lesson worth remembering.

Whether you’re building a cabin in the Montana wilderness or just trying to navigate the challenges life throws at you, your experience matters. Your knowledge has value. But the moment you stop learning from people whose backgrounds and perspectives differ from your own is the moment you start dying intellectually, if not physically.

The frontier didn’t forgive that kind of arrogance. Neither does life. Hrik Bjornstar built a cabin in a cave and saved his neighbors during a blizzard. But more importantly, he showed them that wisdom preserved across generations and cultures might matter more than individual experience alone. That’s why his story survived long after the cave cabin collapsed.

Because it’s not really about the building, it’s about the man who built it and the community humble enough to learn from him. Sometimes the person everyone calls a fool is the only one wise enough to prepare for what’s coming. And sometimes survival depends less on being right and more on being willing to admit you might be wrong.