The first thing hit them before the noise, before the scale, before the impossible truth of what they were seeing. The smell, blood and steam, the rendered fat, the cold smoke, the thick animal scent of 10,000 cattle pressed together in wooden pens stretching toward the horizon in every direction. It was August 1944, and 47 German prisoners of war stood at the gates of the Union stockyards on the south side of Chicago, watching the heart of American industry pound before them with a rhythm that never stopped. They had

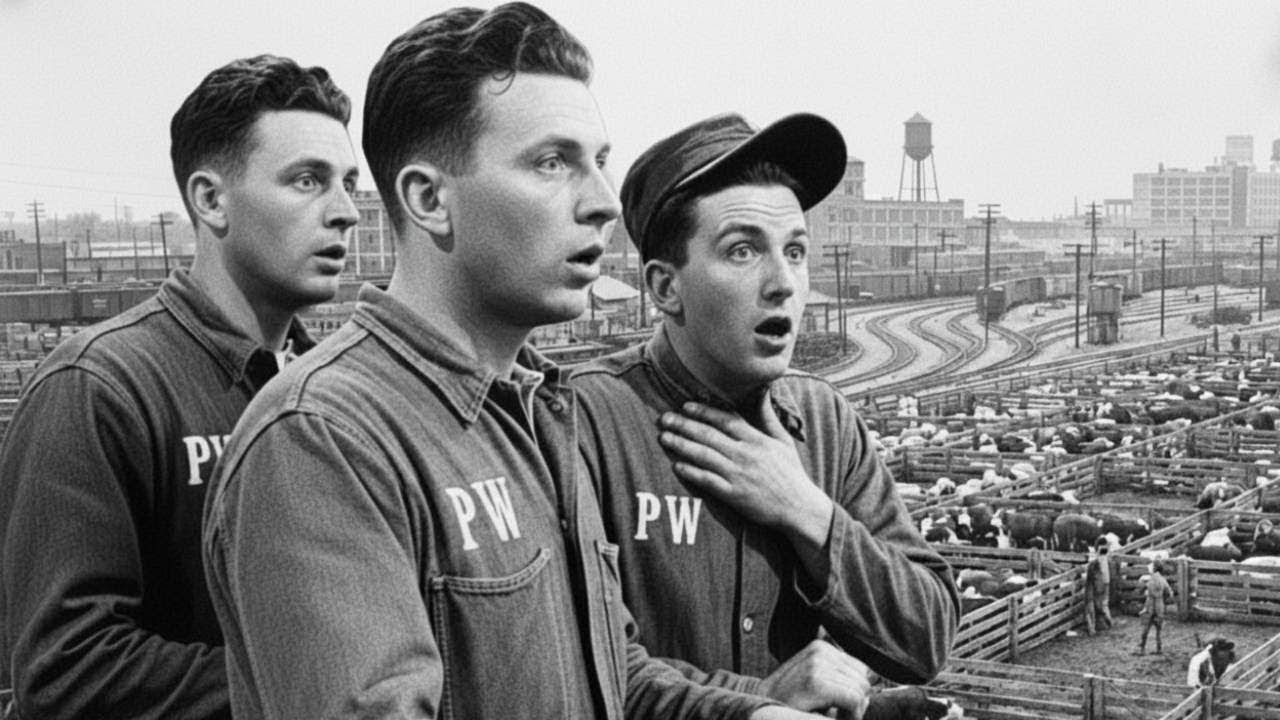

arrived by army truck from Camp Grant, 90 mi northwest, their canvas covered transport, rumbling south through the flat Illinois farmland at dawn. They wore faded denim workc clothes stencled with the letters PW in white paint. Their faces still carrying the dust of yesterday’s agricultural detail. Most had been captured in North Africa or Italy.

A few had survived the Eastern Front before their transfer west. None of them had expected this. The Union stockyard stretched nearly a square mile, the largest livestock market in the world, processing over 400 million animals since its founding in 1865. That morning, cattle cars arrived at the rate of one every 3 minutes. The clang of iron gates echoed against brick packing houses rising five stories high.

Steam whistled from processing plants where the temperature exceeded 100°. Despite the industrial fans spinning overhead, a German corporal named Heinrich stood at the edge of the unloading platform. His surname was preserved only as an initial in a transport manifest now held at the National Archives.

He watched American workers in blood splattered aprons guide cattle through shoots with mechanical efficiency. Heinrich had worked in a small slaughterhouse in Bavaria before the war. Nothing had prepared him for this. “How many?” he asked an American guard in halting English, gesturing toward the endless pens. The guard shrugged. “On a good day, 80,000 head.

Hugs, too. More hugs than you can count.” Hinrich said nothing. But later a fellow prisoner recalled his hands began to tremble, not from fear, but from the sudden visceral recognition that everything he had been told about America was wrong. The Reich’s propaganda had been relentless. America was weak, decadent, incapable of sustained industrial effort.

Its factories were inefficient, its workers lazy, its population mongrel, lacking discipline or racial purity. Now these prisoners watched the largest meat processing operation on earth, feeding armies fighting in France, Italy, and the Pacific, pushing steadily toward the borders of the fatherland itself. A photograph from that August visit survives in the Chicago History Museum archives.

It shows men in work denims standing before the limestone entrance of Swift and Company’s main plant. Their expressions are difficult to read, stunned perhaps or simply exhausted. One man shields his eyes from the sun or perhaps from the glare of understanding. The caption reads, “German POW industrial familiarization tour, August 1944.

” But what happened during that tour was anything but simple. These men would walk through the most sophisticated food production system in human history. They would see refrigerated rail cars, mechanical disassembly lines, federal inspection stations, and a labor force that included women, black Americans, recent immigrants, workers of every description the Reich had taught them to despise.

They would see America not as Gerbal’s news reels had shown it, but as it actually was, vast, efficient, indifferent to ideology. The gates swung open. The smell intensified. 47 men walked into the machine. By the summer of 1943, Allied forces had captured hundreds of thousands of Axis soldiers. North Africa alone yielded over 275,000 German and Italian prisoners after Tunisia.

Britain, already strained by bombing and rationing, could not accommodate them. The solution: ship the prisoners across the Atlantic to the empty spaces of the American interior. Over the course of the war, roughly 425,000 German PSWs would be interned in the United States, spread across more than 500 camps in 46 states. Illinois received its share.

Camp Grant near Rockford, Camp Ellis near Tableroveve, and dozens of smaller branch camps. Camp Grant had been a training facility since the First World War. By 1944, it served as both an army reception center and a major P installation. The prisoners lived in wooden barracks arranged in neat rows, surrounded by chainlink fencing topped with barbed wire.

Guard towers stood at each corner, manned by soldiers who seemed as bored as their charges. Daily life was regimented, but not brutal. Prisoners rose at 6:00 a.m. ate breakfast in mesh halls serving the same food as American enlisted men. Eggs, bread, coffee, occasional meat. Under the Geneva Convention, enlisted prisoners could be assigned to labor.

Most camp grant prisoners worked agricultural details. Illinois farms had lost their young men to the draft, and the harvest could not wait. German PS corn, bailed hay, loaded grain into silos. They worked alongside American civilians, often elderly farmers or teenage boys, and discovered, to their surprise, that their enemies did not hate them.

A letter intercepted in September 1944 captured this confusion. The farmers share their lunches with us. Yesterday, a woman brought apple pie. She knew I was the enemy and still she smiled. I do not understand these people, but I am beginning to respect them. The stockyard tours were part of a broader war department initiative.

Officially, the goal was practical. Exposing prisoners to American industrial capacity might accelerate the psychological process of accepting defeat. Philosophically, planners understood these men would eventually return to Germany. What they believed about democracy, industrial organization, and the possibilities of peace could shape Europe for generations.

The first organized tours from Camp Grant departed in July 1944. Small groups of selected prisoners, deemed psychologically stable and not fanatical, traveled to Chicago for supervised visits to industrial facilities. The stockyards were a favorite destination along with McCormick Reaper works, Pullman rail car factories, and the massive grain elevators along the Chicago River.

Prisoners traveled in canvas covered army trucks, departing before dawn to maximize exposure. Armed guards accompanied them, though incidents of escape were rare. Most simply watched, absorbed, struggling to reconcile what they saw with what they had been taught. The first beat of transformation came on the killing floor.

German prisoners were escorted through Swift and Company’s main plant in groups of eight, accompanied by guards and company representatives who explained each stage. The plant processed roughly 12,000 cattle per day, moving from live animal to packaged meat in less than 45 minutes, a pace unimaginable in any German facility they knew.

Efficiency was not just mechanical. It was organizational. Each worker performed a specific task. Stunning, bleeding, skinning, gutting, splitting with movements so precise they seemed choreographed. Overhead chains moved carcasses station to station without paws. Nothing was wasted. Blood became fertilizer. Bones became glue.

Organs became pharmaceuticals. A German sergeant who had worked in industrial planning for the werem stood watching the disassembly line for 10 minutes. When an American foreman asked if he had questions, the sergeant replied quietly, “We designed our factories for war. You designed yours for everything.

” The second beat came in the refrigerated warehouse. Massive cold storage rooms held sides of beef hung in rows beyond sight. Temperature precisely 34° F, preserving meat without ice crystals. Technology on this scale was unlike anything the prisoners had seen. They marveled at American supply chain capabilities, contrasting them with their grim experiences on the Eastern Front, where supply lines collapsed under weather and distance.

How do you keep it from spoiling? A corporal asked. Ammonia compression, replied the guard, who barely understood it himself. Same system from here to San Francisco. The third beat occurred in the cafeteria. At noon, prisoners ate the same meal as Swift employees. Beef stew, bread, mashed potatoes, coffee, pie. What astonished them was the diners themselves.

black workers beside white workers, women in bloodstained aprons next to male supervisors, Mexican laborers speaking Spanish, Polish and Italian immigrants, workers of every background. The German lieutenant reportedly asked his escort, “How do you maintain discipline with such variety?” The captain replied simply, “They all cash the same paycheck.

That’s discipline enough.” The fourth beat came as the prisoners departed. Chicago’s summer pressed down, humid and heavy shift change at Swift. Hundreds streamed through the gates, tired, sweaty, heading home. These were free people earning wages, feeding an army, steadily crushing the Reich. One German private, barely 20, began to cry.

No one asked why. Perhaps no one needed to. The engines started, canvas flaps lowered. 47 men began the long ride back to Camp Grant, carrying images that could not be unseen. Summer faded into autumn. Stockyard tours continued through fall 1944 and early 1945. Hundreds of prisoners passed through swift McCormick grain elevators, each returning quieter, carrying impressions that would take years to process.

The transformation was gradual. Many remained committed to Nazi ideology. Others adapted, preserving beliefs in private while outwardly compliant. Yet for a significant number, the tours marked a turning point. The scale of American industry, the diversity of the workforce, the abundance of food, these became evidence in an argument they could not win.

Berlin fell in April 1945. Hitler died. The Reich collapsed. Camp Grant prisoners listened to radio broadcasts announcing Germany’s surrender. On May 8th, some wept, some sat in stunned silence. A few refused to accept it. Repatriation was slow, complicated by postwar chaos. The first prisoners departed late 1945, the last in 1946.

They returned to a homeland that no longer existed. What did they carry back? Some applied American methods to postwar industry, rebuilding Germany. Heinrich, the corporal, survived, but his fate is unknown. The Union stockyards closed in 1971. Today, only the limestone gate remains. Camp Grant became a municipal airport and industrial complex.

Yet that encounter, the moment enemies walked through the machine, saw defeat written in beef and steam, refrigeration and cafeteria lines, remains in history. It reminds us wars are won not just on battlefields, but in factories, in fields, in the daily labor of ordinary people who may never fire a shot. The August sun set over Chicago in 1944, painting stockyard smoke stacks in gold and orange.

The prisoners rode north through gathering darkness toward a camp that was not home, toward a future they could not imagine. Behind them, the machines kept running. They always kept running. And somewhere in the silence of each man’s thoughts, a belief was dying, not with thunder, but with a quiet hum of refrigeration, the clang of overhead chains.

The simple truth of a cafeteria where every worker, regardless of race or origin, cashed the same paycheck. That was America in 1944. Imperfect, contradictory, often cruel in its ways, but undeniable, unstoppable. The prisoners had seen it, and they could never unsee it again.