April 1942, a conference room in Whiteall. Vice Admiral Lord Louie Mountbatton poses a single question to Jeffrey Lloyd, Secretary for Petroleum. Can we lay an oil pipeline across the English Channel? Lloyd consults three of Britain’s top engineering advisers. Their answer is unanimous, impossible. No submarine pipeline has ever been laid across such distances.

The channel’s tidal conditions would destroy any conventional pipe and any attempt would need to happen in a single night to avoid German detection. The experts agree it cannot be done. Then Dr. AC Hartley hears about the problem. Within 6 weeks he will prove every expert wrong. This is the story of Operation Pluto pipelines under the ocean.

A project so secret that Germany never discovered it. So ambitious that it laid 21 pipelines beneath the English Channel. and so audacious that it pioneered technologies still used in offshore oil production today. The experts said it was impossible. British engineers did it anyway. To understand why Pluto mattered, you need to understand the scale of the fuel problem facing Allied planners in 1942.

A modern mechanized army runs on petroleum. Tanks, trucks, jeeps, aircraft, everything needs fuel. And the quantities involved were staggering. A single Sherman tank consumed roughly one gallon of fuel per mile traveled. A heavy bomber required over 2,000 gall for a single mission over Germany. Multiply these figures across thousands of vehicles and aircraft, and Allied forces in Europe would eventually consume over 1 million gallons of fuel every single day.

That fuel had to cross the English Channel somehow, every drop of it, without interruption, while German forces did everything possible to stop it. The conventional solution was tanker ships. But tankers presented enormous problems. They were slow, typically managing only 10 knots in convoy formation. They were vulnerable to German submarines and aircraft.

Between 1939 and 1943, Yubot had sunk hundreds of Allied tankers, sending millions of tons of fuel to the bottom of the Atlantic along with thousands of merchant seaman. They required functioning ports to unload, and ports were exactly what the Germans would destroy before retreating. The port of Sherborg, the closest major harbor to the planned invasion beaches, would certainly be demolished if the Allies approached.

Tulon had shown what the Germans did to ports they could not hold. Even in calm conditions, transferring fuel from ship to shore was dangerous and inefficient. Tankers needed deep water births, working cranes, storage facilities, and fire safety equipment. A single torpedo or bombing raid could eliminate thousands of tons of desperately needed fuel along with the ship carrying it and the men crewing it.

Jerry cans offered an alternative for small quantities, but the numbers quickly became absurd. Moving 1 million gallons per day in jerry cans would require over 200,000 individual containers. Each one filled, sealed, transported, and emptied by hand. The logistics were impossible at scale. What planners needed was a continuous, invisible, invulnerable supply line.

A pipe running directly from English storage tanks to Allied vehicles in France. The problem was that no such technology existed. Conventional steel pipelines were rigid. They required welding on site piece by piece. Laying one across 70 mi of seabed in waters patrolled by German aircraft and submarines in the middle of a war was engineering fantasy.

Also, everyone believed until Clifford Hartley got involved. Hartley was chief engineer of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. He had spent years working with high-press pipelines in Iran, where 3-in diameter pipes delivered 100,000 gallons daily at pressures of,500 lb per square in. His insight was deceptively simple. Forget large diameter pipes.

Forget rigid steel. Instead, create a continuous, flexible pipe resembling submarine telegraph cable. Small enough to coil in a ship’s hold. strong enough to withstand crushing ocean pressures and deployable at speed like laying telephone wire. According to Anglo Iranian company records, Hartley sketched his initial concept within days of hearing about the problem.

Sir William Fraser, the company’s chairman, agreed to fund immediate trials. On May 10th, 1942, workers laid a 120 prototype across the river Medway. It failed. Lead extruded through gaps in the protective steel tape, but the core concept was proven. A flexible pipeline could be manufactured, coiled, and deployed from a moving vessel.

Hartley’s team refined the design rapidly. The result was HK’s cable, named for Hartley, Anglo Iranian, and Seammens, the electrical company that helped develop it. Manufacturing mobilized an entire nation’s industrial capacity. British companies including Seaman’s Brothers, WT Henley, British Insulated Calendarers, Cables, Pirelli, Johnson and Phillips, and the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company all contributed.

WT Henley alone consumed 8,000 tons of lead and 5,600 tons of steel. American firms joined the effort. Phelps Dodge, General Electric, Okonite Calendars, and General Cable produced 140 nautical miles of the total 710 nautical miles manufactured. The Tilbury factory achieved production rates of 3 to four nautical miles daily.

Phelps Dodge completed their entire American contribution in just 162 days from contract signing to final shipment. The specifications were remarkable. A 3-in internal diameter lead tube formed the core. Seven protective layers surrounded it. Impregnated paper tape, cotton tape, four layers of mild steel strip, jute bedding, 57 galvanized steel armor wires, and outer jute servings for protection.

Each nautical mile weighed between 55 and 67 tons. Working pressure reached 1,500 lb per square in. Bursting pressure exceeded 4,000. By December 1942, HMS Holdfast successfully laid 30 mi of haze cable across the Bristol Channel from Swansea to Ilframe. The pipe held at full pressure in rough weather, laid at 5 knots. What experts had declared impossible 7 months earlier was now proven technology.

But Hayes had a critical weakness. It consumed enormous quantities of lead, 24 tons per nautical mile, plus 7 1/2 tons of steel tape and 15 tons of armor wire. Wartime Britain faced severe lead shortages. Every ton used for pipelines was a ton unavailable for ammunition, batteries, and other war materials. The system needed an alternative that used less strategic material.

That alternative came from Bernard Ellis of Burma Oil Company and HA Hammock of Iraq Petroleum Company. Their design, called Hamill, took a radically different approach. Instead of flexible lead wrapped in protective layers, Hamill used bare 3 and 1/2 in steel pipe with walls just over 5 mm thick. Each nautical mile weighed only 20 tons, roughly 1/3 the weight of haze.

The trade-off was durability. Without protective layers, Hamill pipe would corrode and wear. Engineers designed it to last just 6 weeks, long enough to establish proper supply lines before conventional methods took over. In practice, Hamill pipes exceeded this lifespan, lasting between 52 and 112 days.

But the durability gap remained stark. Every HI’s cable that was satisfactorily laid remained operational until deliberately shut down. Hamill pipes failed repeatedly from seabed abrasion, corrosion, and mechanical stress. The engineering challenge with Hamill was deployment. Rigid steel pipe cannot coil in a ship’s hold like flexible cable.

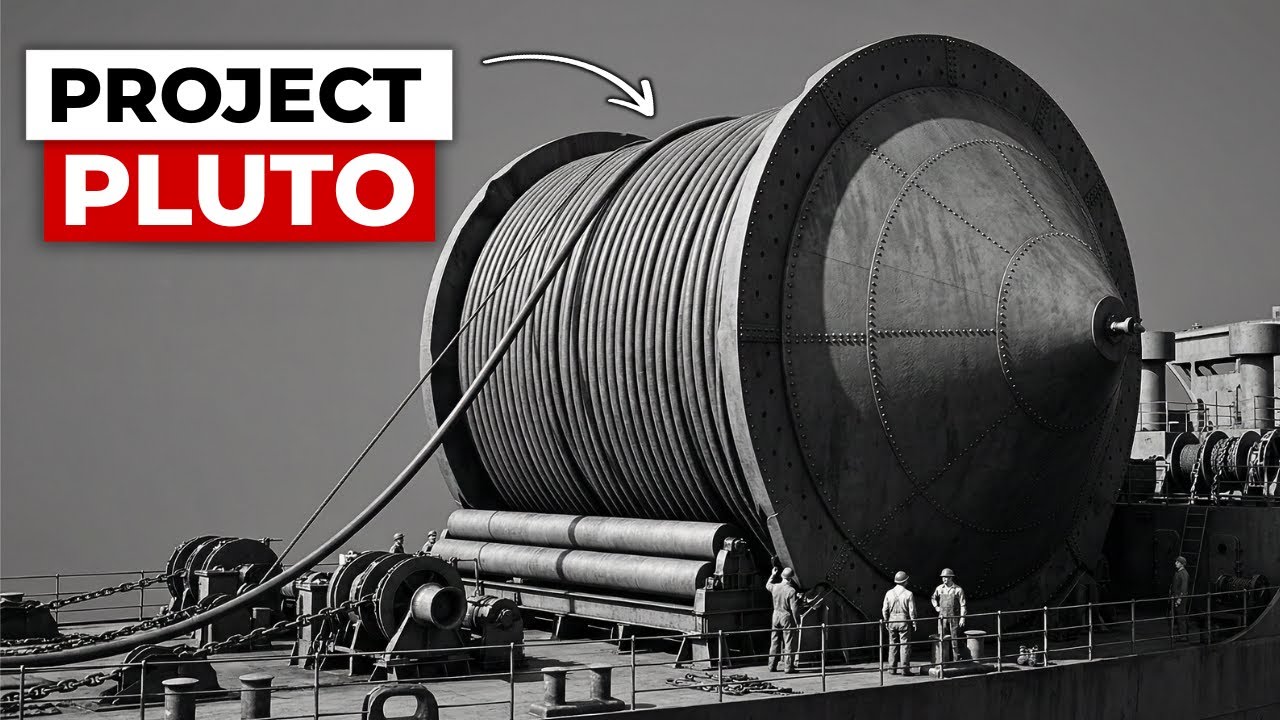

Ellis and Hammock solved this with one of the war’s most extraordinary inventions, the Conundrum. These were massive floating drums, 60 ft long and 40 ft in diameter, displacing 1,600 tons when loaded with 70 to 90 m of pipe wound around their cores. The pipe was flash welded in 40ft sections, then joined into 4,000 ft lengths on factory conveyor lines.

Women inspectors checked every weld. The completed pipe was wound onto the drums core under precise tension. Ocean rescue tugs towed the conundrums across the channel while the drums rotated in the water, driven by the resistance of the sinking pipe, unrealing their cargo directly to the seabed at controlled speeds.

Six were built at a cost of £30,000 each. Each represented a floating factory, a storage facility, and a deployment system combined into a single vessel. Nothing like them had ever existed. If you are finding this deep dive into British engineering interesting, take a moment to subscribe. It costs nothing and helps the channel grow.

Now, let us see what happened when these impossible pipelines met the impossible conditions of the English Channel. The original plan called for Pluto to begin pumping fuel on D-Day itself, June 6th, 1944. That did not happen. The pipelines were designed to run from the aisle of White to Sherborg, a distance of roughly 70 nautical miles. But Sherbore needed to be captured first.

Planners expected the port to fall by D plus8. It actually held out until D +21, June 27th. And when it finally fell, retreating Germans had demolished the harbor so thoroughly that it could not receive fuel anyway. Operation Bambi, the code name for the Sherborg route, finally launched on August 12th, 1944, more than 2 months after D-Day. Then everything went wrong.

HMS Latimer laid the first 65mm haze pipeline in just 10 hours. An extraordinary technical achievement. Then an escorting destroyer’s anchor destroyed the entire line. 2 days later, HMS Sancraftoft attempted a second laying. The pipe fouled in support ship HMS Algerian’s propeller. A third attempt using Hamill pipe failed because 10 tons of barnacles had grown on conundrum 1 during its weight, preventing the drum from rotating.

A fourth attempt saw the pipe break 29 nautical miles out. According to official war diaries, success finally came on September 22nd, 1944. The first operational pipeline began delivering 56,000 imperial gallons daily. A week later, a Hamill pipe joined it. Then on October 3rd, both failed. The haze from a faulty coupling.

The haml from a sharp edge on the ocean floor that wore through the unprotected steel. Operation Bambi was terminated on October 4th, having delivered just 3,300 tons of fuel total. The shorter Dumbo route proved more successful, running from Dungeoness to Bologna, a distance of only 23 to 31 nautical miles. The route presented fewer technical challenges.

HMS Sanraftoft laid the first pipeline in 5 hours on October 10th. By December, 17 pipelines were operational, 11 HI’s cables and six Hamill pipes. The system eventually extended inland to Calala, Antwerp, Einhoven, and ultimately Emer on the Rine. The final statistics reveal both triumph and disappointment.

Pluto delivered 180 million imperial gallons of fuel by wars end. That sounds impressive until you learn it represented just 8% of the 4.3 million tons of petroleum sent from Britain to Allied forces. During the critical advance across France from June to October 1944 when fuel shortages nearly halted General Patton’s third army, Pluto contributed approximately 150 barrels daily. That was 0.

16% of consumption. Peak performance arrived too late to matter. Pluto reached its design target of 1 million gallons per day on March 15th, 1945, 9 months after D-Day, with Allied victory already assured. By April 1945, Dumbo delivered 4,500 tons daily to the Rhin Front, but the Battle of Normandy had already been won without Pluto’s contribution.

Alternative supply methods had filled the gap. The Red Bull Express, a truck convoy system running from August 25th to November 16th, 1944, delivered 412,000 tons of supplies in 83 days. Coastal tankers supplied between 2,500 and 3,000 tons daily to ports at Oand and Ruan once they were captured and repaired.

The Malbury artificial harbors had already delivered 7 12 million gallons by the end of June. Package fuel in jerry cans for all its inefficiency kept Patton’s tanks moving when nothing else could. The official historian Derek Payton Smith delivered a blunt verdict. Pluto contributed nothing to Allied supplies at a time that would have been most valuable.

Dumbo was more successful, but at a time when success was of less importance. Yet dismissing Pluto as failure misses its true significance. Consider the security measures alone. They rivaled any wartime deception operation. Pumping stations disguised themselves as bungalows, ice cream shops, garages, old forts, and amusement parks.

The sandown station on the aisle of white became Brown’s ice cream, complete with a painted facade and a menu board. Dungeonous facilities looked like fisherman’s cottages, weathered and unremarkable against the coastal landscape. Anyone delivering supplies had to ask for Captain Jones before proceeding. The wrong question meant immediate detention and interrogation.

At Dover, architect Basil Spence, later famous for designing Coventry Cathedral, constructed a 3acre fake oil dock from scaffolding, fiberboard, and old sewage pipe. The installation included dummy tanks, fake valves, and connecting pipes that went nowhere. Wind machines created dust clouds to simulate activity. Military police in authentic uniforms guarded fake pipelines and storage tanks around the clock.

Anti-aircraft batteries surrounded the installation. King George V 6th personally inspected the facility during a royal tour. Photographed examining fake equipment that existed solely to deceive German reconnaissance. The Luftvafer was permitted to overfly only above 33,000 ft, too high to distinguish real infrastructure from theatrical props.

The deception succeeded completely. No German attacks on Pluto operations are documented in any surviving records. The dungeonous pumping station sat within range of German guns in France, yet never drew fire. Records remained classified for 30 years with declassification occurring around 1975. Germany had nothing comparable.

While German engineers had laid short river pipelines, they possessed no technology for continuous submarine deployment at scale. The conundrum drums, the flexible HIS cable, the rapid laying techniques, all represented capabilities that existed nowhere else in the world. The true legacy emerged decades later. Pluto was the world’s first undersea oil pipeline of significant length.

Nothing comparable had ever been attempted, let alone achieved. The project proved that continuous flexible pipe could be deployed rapidly across ocean floors, a concept that transformed offshore petroleum production. The real laying technique pioneered by Pluto reappeared in the offshore industry by the 1960s. Modern pipe laying vessels use coiled pipe technology descended directly from Pluto methods.

When the pipe laying vessel MV Solitaire laid pipe to a record depth of 9,100 ft in 2007, it employed evolved Pluto principles. The fundamental insight that Clifford Hartley had in April 1942 that pipeline could behave like telegraph cable remains the foundation of subca infrastructure worldwide. Every North Sea oil platform, every offshore drilling operation, every subc pipeline connecting wellheads to processing facilities owes something to lessons learned beneath the English Channel.

In 1944, the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors granted Clifford Hartley £9,000 and Bernard Ellis £5,000 for their contributions. Modest sums for innovations that created billion pound industries pipeline recovery operations from September 1946 to October 1949 salvaged 22,000 of 23,000 tons of lead and 3,300 of 5,500 tons of steel.

The sale of recovered materials largely covered disengagement costs. Approximately 10% of the original pipelines remain on the channel floor today. Physical remnants survive across southern England. Pluto Cottage at Dungeoness, a former pumping station disguised as a seaside cottage, served as a bed and breakfast before becoming a private residence.

Five Pluto bungalows at Leonard Road in Great. Three pumping stations and two staff quarters now serve as family homes, some with added second stories. Yellow marker posts trace the pipeline route across Romney Marsh. Shanklin Chine on the aisle of white houses the primary museum display featuring cross-sections of actual pipeline and visible remnants of the feeder system.

The romantic narrative, a secret pipeline that fueled D-Day’s victory collapses under scrutiny. Pluto arrived too late, delivered too little, and failed repeatedly when it mattered most. Major General Tickle summarized bluntly in his postwar assessment. We gained very little from Pluto and Dumbo. General Eisenhower’s praise of the system as second in daring only to the Malbury harbors acknowledged ambition rather than results.

But engineering achievement cannot be measured solely by wartime impact. British engineers solved problems that the world’s experts had declared impossible. They manufactured 710 nautical miles of submarine cable across dozens of factories on two continents. They laid 21 pipelines across one of the world’s most treacherous waterways.

They maintained secrecy so complete that the enemy never struck a single blow against the operation. And they proved technologies that would shape energy infrastructure for generations. April 1942, three experts tell Vice Admiral Mount Batton that a channel pipeline cannot be done. 40 months later, 17 pipelines pump fuel beneath those same waters.

The experts had looked at the problem and seen impossibility. Clifford Hartley looked at the same problem and saw telegraph cable. That is the British engineering difference. Not just solving problems, but refusing to accept that problems are unsolvable. Pluto cost £4,428,000. Its contribution to D-Day was negligible.

Its contribution to offshore engineering was transformational. The Impossible Pipeline did not win the war, but it proved that impossible was just a word that people used when they lacked the imagination to find solutions. British engineers had that imagination and they changed the world with