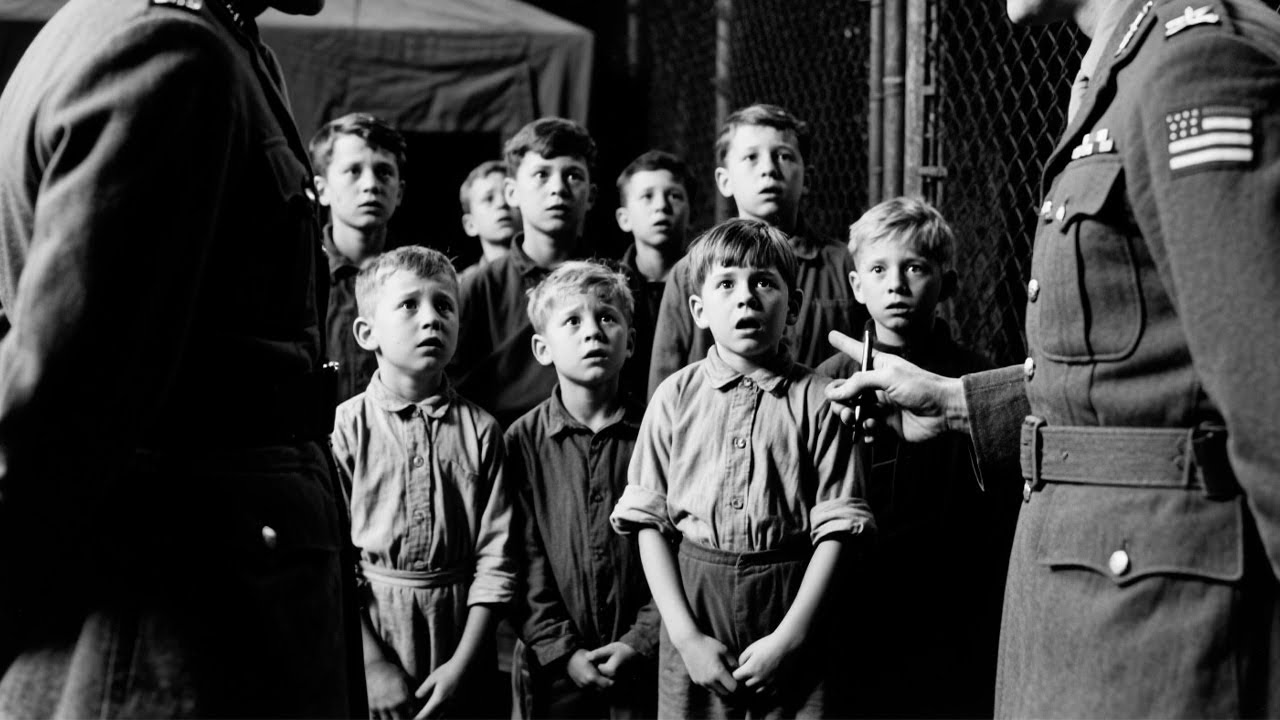

“Are We Allowed to Smile?” — German POW Children Asked After Entering an American Camp

Chapter 1: “Are We Allowed to Smile Here?”

Camp Aliceville, Alabama, October 1945.

The guard tower threw long shadows across the compound as thirty-seven German prisoners stood in formation for processing. They were lined up neatly, as if neatness could protect them. Their faces were carefully blank. Their backs were too straight. Their hands hung stiffly at their sides with the unnatural control of boys who had learned—too early—that emotion invited trouble.

.

.

.

The American soldiers watching them did not know where to look. In battle, you can hate a uniform. In paperwork, you can process a number. But these were not hardened veterans. They were fourteen to seventeen years old—children drafted during Germany’s last desperate months when the regime had run out of men and started taking boys from classrooms.

A chaplain stood beside Colonel Henderson, the camp commander, ready to translate. Henderson was a broad-shouldered man with a steady voice and an expression that rarely softened in front of troops. He spoke with deliberate calm, not as a conqueror enjoying power, but as an officer trying to do a difficult duty without losing his decency.

The chaplain translated sentence by sentence.

“You will receive adequate food and medical care.”

“You will have a routine.”

“You will have light work appropriate to your age.”

“You will be safe here until repatriation can return you to your families.”

The boys stared straight ahead. Words from adults meant little. They had heard promises in Germany, too—grand promises that had led them into trenches and burning streets. They had learned not to believe until belief could be proven with repeated evidence.

Then one boy raised his hand.

It was an old reflex, schoolroom behavior pushing through months of fear: the simple act of asking before speaking. The movement was so unexpected that several Americans shifted uncomfortably, as if the raised hand itself accused them.

The boy’s name was Peter Hoffman. He was fifteen, from Hamburg, with hair cut too short and eyes that looked older than his face. He spoke in careful German, and the chaplain translated.

“Are we allowed to smile here?”

A silence fell, heavy and immediate.

Not because the question was complicated—but because it was plain. It revealed a world in which a child did not know whether happiness was permitted. A world where smiling had become dangerous enough to require permission.

Colonel Henderson’s jaw tightened. The anger that flickered on his face was not directed at the boy. It was aimed at the unseen architects of the boy’s fear.

The colonel answered slowly, making sure every word would land.

“You are not only allowed to smile,” the chaplain translated, voice thickening. “You are encouraged to smile. If something makes you happy—food, a joke, a game—you may laugh. No one here will punish you for showing joy. That is not how we treat prisoners. And it is especially not how we treat children.”

Peter lowered his hand. His face stayed blank, but something had shifted in his eyes—a small crack in the wall. Not trust yet. But the possibility that trust might one day become reasonable.

Chapter 2: A Boy Becomes a Soldier

Peter had been twelve when the war began—old enough to sense that something enormous had started, too young to understand what Germany had unleashed. He remembered the parades, the speeches, the flags that seemed to multiply on every building. He remembered his older brother marching away in uniform. He remembered his father—too old for combat—speaking of duty as if duty were a kind of armor.

Peter believed because children believe adults. He believed Germany was defending itself against enemies who wanted to destroy everything German.

By March 1945, belief no longer mattered. Germany was collapsing, and belief did not stop tanks.

In his classroom in Hamburg, a man in uniform came to the door with a list. Boys fourteen and up. Peter’s name. His best friend’s name. Boys who were still learning algebra were now “military age.”

They were given three weeks of training. Three weeks to fire rifles. Three weeks to throw grenades. Three weeks to dig trenches. Three weeks to obey.

The regime did not waste time on subtlety. It was too desperate. There was no room left for convincing speeches. The state commanded and the children went because refusal meant consequences—sometimes not only for the boy, but for his family.

Peter’s mother cried when he left. She did not speak of glory. She whispered one word, the only honest strategy left.

“Survive.”

He was sent near Berlin with other boys—thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen—children ordered to stop armies that had already proven unstoppable. Peter saw boys die. Not in heroic stories, but in the ugly intimacy of reality: blood in mud, pleading voices, eyes wide with terror, hands reaching for help that could not arrive.

When the Soviets overran their position, they took Peter and thirty-six other boys prisoner. The Soviets were rough, hurried, sometimes sharp, but not gleefully cruel. If anything, they seemed almost embarrassed, as if they had expected grown soldiers and found schoolchildren holding rifles.

Soon after, in the chaos following Germany’s surrender, Peter and the other boys were transferred into American custody during exchanges. An American captain had looked at them and said something in English that the translator rendered with quiet disbelief:

“What kind of system sends children to die?”

The Americans still processed them as prisoners of war. Paperwork didn’t know what to do with childhood. But the faces of the American officers showed something the boys recognized even through fear: disgust at what had been done to them.

In late summer, they were put on a ship across the Atlantic with adult prisoners. The crossing was crowded but not inhumane. There was food. There was medical care. The ship ran like a machine that worked—a detail that alone felt foreign after Germany’s late-war shortages.

Then trains. Then the American South. Then Camp Aliceville.

And now Peter stood in formation asking if he was allowed to smile.

Chapter 3: Food, but No Laughter

Colonel Henderson had requested these boys be sent to Aliceville after learning they were scattered among camps built for adult soldiers. Henderson had children. He understood, instinctively, that a teenager’s trauma does not heal by being treated like a hardened man. He ordered separate barracks for the boys, separate schedules, lighter work details, closer medical attention.

He selected staff carefully. Sergeant Miller was assigned to supervise their section—a father of three from Georgia with sons near Peter’s age. Miller wore authority the way good fathers do: firm enough to hold a line, gentle enough to keep the line from becoming a whip.

The first meals revealed how deep the damage went.

The camp served adequate food—nothing extravagant, but nutritious and steady. The boys ate intensely, cleaning plates with the urgency of people who had known hunger. Seconds were available, and their eyes flicked up in startled disbelief when they realized they could ask for more.

Yet they ate in silence.

No teasing. No jokes. No arguments over who got the last piece. No ordinary noise.

Miller watched them and felt a quiet disturbance settle in his chest. Teenage boys, in groups, were normally loud. They complained, they laughed, they competed. These boys sat like they were being graded on how invisible they could be.

After dinner Miller approached Peter, who seemed to be the informal center of the group—quietly respected, watched by the others for cues.

Through a translator, Miller asked, “How was the meal?”

Peter answered politely in careful English, learned before the war interrupted everything. “The food is good. Very good. Thank you.”

Miller nodded. “Did you enjoy it?”

Peter hesitated, calculating the safest answer. Then he spoke with a precision that sounded practiced, like a recited statement.

“We are grateful,” he said. “We know we are prisoners. We do not deserve such good treatment. We will work hard to earn what we receive.”

The words landed like a stone.

Miller leaned closer, lowering his voice, as if gentleness needed privacy. “Son,” he said, choosing the simplest truth he could offer, “you don’t earn food. Food is provided because humans need to eat. You’re children. Children deserve to be fed properly. You’re allowed to enjoy a meal without guilt.”

Peter listened, face blank, eyes wary. He nodded because nodding was safe.

But Miller could tell: the boy did not believe him yet.

Words were too easy. The boys needed proof that repeated itself without punishment.

The first week made the pattern painfully clear. They asked permission for everything—using the latrine, getting a drink of water, speaking during free time. They followed rules obsessively, not from respect but from fear. Even recreation felt mechanical. They threw a baseball without joy, kicked a football without playfulness, as if “play” were another duty.

The camp psychiatrist, Major Thompson, examined several boys. His report was blunt.

“These children have combat trauma,” he said. “But also ideological conditioning. They don’t trust adults. They don’t trust authority. They don’t trust their own feelings. Recovery will take time and repeated safety.”

Colonel Henderson called a meeting with every man assigned to the boys’ section.

“These children are our responsibility,” he said. “They didn’t choose the war. They didn’t choose the regime. What we do now matters. We will not add cruelty to their injuries. Treat them as children first. Give them permission to be kids again.”

Permission.

That word became the quiet mission of Aliceville’s boys’ barracks: teaching frightened children that humanity was not something granted and revoked by power.

Chapter 4: The Rabbit Called Hope

The breakthrough came in the third week, not in a speech or a lecture, but in a garden.

Major Thompson had recommended a therapeutic work assignment: tending the camp garden. Gardening was peaceful, repetitive, and—most importantly—unlikely to trigger combat memories the way loud machinery or harsh commands might.

Peter was weeding beside two boys, Friedrich and Hans, working in silence as usual.

A rabbit appeared at the garden’s edge—small, gray-brown, a cottontail that looked as if it belonged to the afternoon light itself. It sat calmly, washed its face with its paws, and showed no fear of the boys.

Friedrich noticed first. He froze, then slowly smiled—an unpracticed movement, as if the muscles of his face had forgotten what smiling felt like.

“Look,” he whispered in German. “It’s not afraid of us.”

Hans looked too, and a smile flickered across his own face, fragile as a match flame.

Peter turned last. He saw the rabbit and felt something unfamiliar move inside him. The rabbit was not a symbol. It was just an animal, alive and unconcerned, behaving as if the world was not made only of danger. It represented a simple truth Peter had not allowed himself to imagine: peace could exist in small pockets, even now.

His mouth lifted into a smile.

Not a forced grin for propaganda. Not a mask to avoid punishment. A real smile, quiet and surprised.

Sergeant Miller saw them—three boys standing still with softened faces—and understood instantly that something important was happening. He approached slowly, careful not to startle them into snapping back into blankness.

He spoke in simple English they were learning.

“Nice rabbit,” he said.

Friedrich answered in broken English, searching for words. “We are… happy. Rabbit is… good. Is this permitted?”

The question again. Permission for joy.

Miller’s throat tightened, but he kept his voice steady, because steadiness was what the boys needed most.

“Yes,” he said firmly. “Being happy is permitted. Always. Especially about rabbits.”

The boys smiled more openly. The rabbit hopped away eventually, and the boys returned to their weeding, but the atmosphere had changed. They talked—quietly—about the rabbit, about birds, about butterflies, about the way the sun made long golden shadows.

That evening Peter approached Miller during recreation time.

“Tomorrow,” he asked in improving English, “may we see rabbit again? May we bring vegetables? Carrots?”

Miller nodded. “Yes. We’ll set some aside. Rabbits like carrots.”

Peter hesitated, then pushed the boundary farther. “May we name it?”

“All good rabbits deserve names,” Miller said.

The boys named it Hoffnung—Hope.

And in the days that followed, something astonishing happened: they began to act like boys again.

Not all at once. Not neatly. Trauma does not leave on schedule. But the rigid formality softened. They began to joke. They argued over small things. They laughed during games—not often at first, but sometimes. When the rabbit appeared, they rushed to the garden like children, not soldiers.

The Americans noticed and did not mock them for it. They guarded that fragile progress the way you guard a small flame in wind: with patience, with routine, with calm.

Chapter 5: School Behind Wire

With the boys’ behavior slowly returning to something human, Henderson expanded education programs. Not political lectures, but actual schooling—math, science, English, history taught without slogans.

Mrs. Patterson, a grandmother from Trinidad, Alabama, volunteered to teach English twice a week. She treated the German boys the way she treated her own grandchildren: firm about lessons, warm about mistakes, generous with praise when effort was sincere.

Peter learned quickly. He had always been a good student, and now learning felt like reclaiming a stolen part of himself. He began to imagine a future beyond survival. He began to imagine returning home and studying again.

Friedrich discovered an eye for art. A guard brought pencils and paper, and Friedrich sketched Hoffnung the rabbit with careful detail—ears alert, body poised, the small creature rendered with the seriousness of someone drawing a doorway out of darkness.

Hans learned guitar from a guard who played music in his free time. Music gave the boys a safe channel for feeling. When Hans played in the evenings, the barracks grew quiet—not from fear this time, but from listening.

Nightmares still came. Loud noises still startled them. Sometimes a boy would freeze, eyes empty, trapped in memory. The medical staff worked gently. The guards learned to approach slowly, speak calmly, and never use humiliation as control.

In December, the camp held a Christmas celebration. There was a special meal. There were small gifts from Red Cross packages—paper, pencils, candy. The boys made decorations and sang German carols.

During the service, Peter stood up. He did not ask permission. He simply spoke, and one of the guards translated for the Americans.

“We came here expecting punishment,” Peter said. “Instead, you showed kindness. You fed us. You cared for our health. You taught us. And you taught us something simple but important: that we are allowed to smile.”

He paused, voice steadying.

“Hoffnung the rabbit taught us this first. But you reinforced it every day. We will remember.”

Several guards wiped their eyes. Colonel Henderson, who rarely showed emotion, did not bother hiding the tears on his face. Not because he wanted praise—but because he understood what had been repaired here: not politics, but childhood.

Chapter 6: Going Home With the Answer

Spring 1946 brought repatriation schedules. The boys would return to Germany in a group, processed through displacement centers, reunited with families if possible.

They wanted to go home. They were also afraid of it.

Aliceville had been a prison, yes—but it had also become the first safe place many of them had known in months. Leaving safety felt like stepping off solid ground.

Sergeant Miller gave Peter an address in Georgia. “Write if you need to,” he told him. “Even if it’s just to say you’re alive.”

When the trucks arrived, the boys boarded quietly. They looked back at the wire, the towers, the garden where the rabbit had appeared, and the men who had guarded them without crushing them.

Peter carried a few things: his journal, Friedrich’s drawing of Hoffnung, and the memory of an American colonel answering a question that should never have needed to be asked.

Back in Hamburg, Peter found ruins. Their apartment was gone. His father had not survived the war’s final months. But his mother was alive, and his younger sister had survived with relatives. They built a new life in a displaced-persons camp, then in whatever housing reconstruction provided.

Peter did what he had learned.

When he felt joy, he allowed it to show. When his sister cried, he did not tell her to be strong in silence—he told her feelings were human. When adults tried to replace one rigid system with another, he kept a stubborn loyalty to truth and decency.

He became a teacher, then a school administrator, devoted to giving children what he had been denied: education without indoctrination, discipline without cruelty, authority without humiliation.

In his office, he framed Friedrich’s drawing of Hoffnung the rabbit. Students sometimes asked what it meant.

Peter would look at the sketch, then answer gently, the way Sergeant Miller once had.

“It means,” he would say, “that even after fear, it is allowed to smile.”