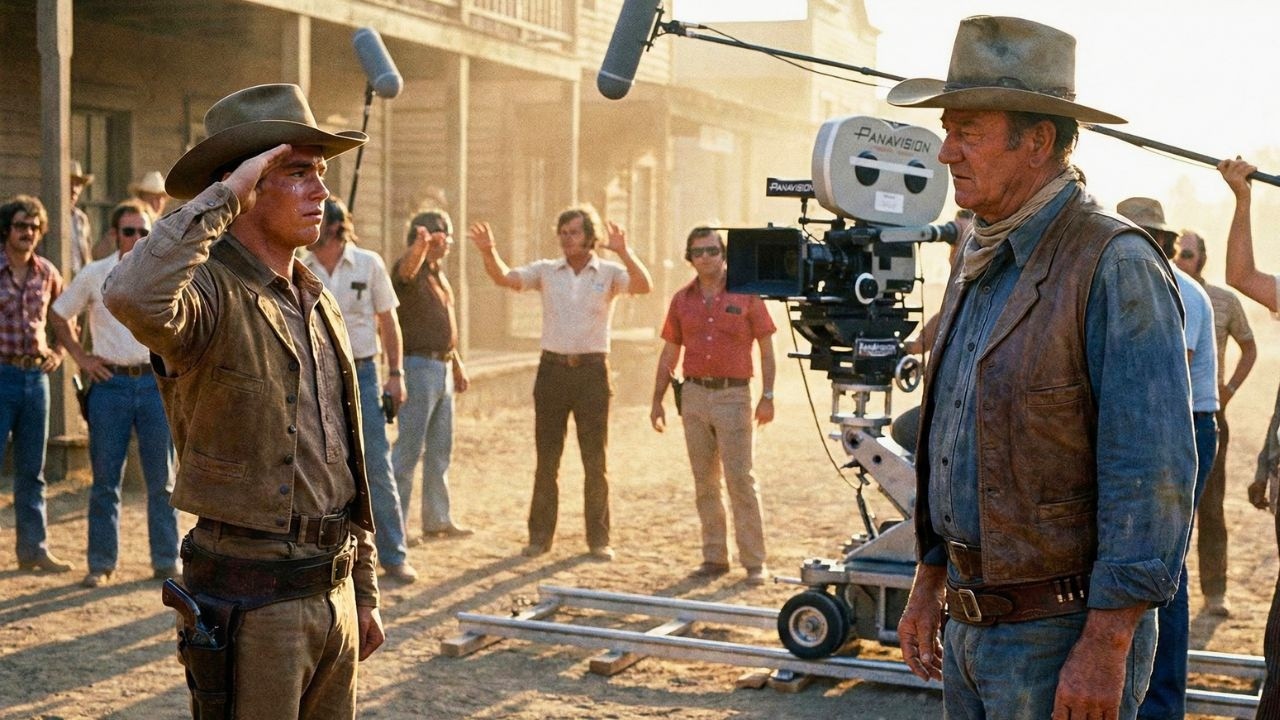

A man called John Wayne. Sir. Wayne stopped the scene, walked toward him, and said nothing, but everyone understood. Monument Valley, 1972. Summer heat thick enough to taste. The kind of day where the desert holds its breath and waits. They were filming the Cowbas. John Wayne 64th Western. Though no one was counting anymore.

The cameras had been rolling since dawn. Dust settled on everything. Extras in period costume stood in position, waiting for the director to call action for the seventh take of a simple town square scene. Among them, a thin young man in his late 20s. Costume, weathered work shirt, faded vest, hat that didn’t quite fit.

Name: Michael Ree. Recent occupation: United States Marine Corps, Second Battalion, Fifth Marines, Vietnam. Two tours. home for eight months now. Working as a film extra because the VA checks weren’t enough and because standing still in costume was easier than explaining to civilians what Keyan had been like.

Michael didn’t talk much on set. None of the other extras knew he’d been overseas. He showed up early, took direction, did his job, left. The costume supervisor noticed his posture. too military, too straight, and kept trying to get him to slouch more naturally. He couldn’t. Two years of standing watch doesn’t leave your spine easily.

The scene was routine. Town’s people gathering, Wayne’s character addressing them, exposition about a cattle drive. Seven takes already because the light kept changing and the director wanted it perfect. Between takes, the crew reset. Extras milled around in the shade. Michael stood apart as he usually did near the false front saloon, looking out at the real desert beyond the constructed town.

John Wayne walked past him, close enough to touch the Duke himself, 6’4 of American mythology in worn leather and dusty denim, moving with that familiar rolling gate despite the pain everyone on set knew he carried. Lung cancer, surgery, the big C. He didn’t complain, just kept working. Michael reacted without thinking. Two years of military conditioning overriding 8 months of civilian life.

He snapped to attention, spine straight, heels together, right hand rising in a perfect salute. Sir, he said, clear, respectful. The way you address a superior officer. John Wayne stopped walking. The set didn’t go silent immediately. That came a few seconds later as people noticed the stopping, the stillness, the way Wayne had frozen mid-stride like someone had pulled his plug.

He turned slowly, boots pivoting in the dust, facing the young man who was still holding that salute, hand trembling slightly now because this was John Wayne, and Michael had just made himself visible. And oh god, what had he done? Wayne’s face showed nothing. That famous mask of weathered granite. Eyes that had seen a thousand scripts and 10,000 setups and a million moments of pretend conflict.

Those eyes looked at Michael really looked taking in the two straight posture. The military haircut not quite grown out. The way the costume hung on a frame that had lost weight it couldn’t afford to lose. The hand holding that salute with textbook precision. The assistant director started to step forward. Clearly, this extra had broken protocol.

Clearly, Wayne was annoyed. Clearly, they needed to move this kid along and get back to filming. Wayne raised one hand. Not quite a stop sign. Just wait. Wayne didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to. He walked toward Michael. Three steps. Four. close enough that Michael could see the lines around Wayne’s eyes, the gray and the stubble.

The makeup hadn’t quite covered the small scar on his jaw from a stunt gone wrong 30 years ago. Wayne stopped, looked at the salute, looked at Michael’s face, looked at the dog tags just barely visible beneath the costume shirt collar. Then John Wayne did something he never done on any film set in 40 years. He returned the salute.

Proper form hand to the brim of his cow by hat, held it, not the casual movie gesture he’d done in a dozen war pictures. A real salute, the kind that means something. He held it until Michael could lower his hand. Protocol observed. Respect acknowledged. Only then did Wayne speak. one word. Quiet enough that only Michael and the few people standing closest could hear.

Marine. Michael’s voice came out rougher than he intended. Yes, sir. Second battalion fifth. Wayne nodded. Once understanding passing between them in that nod. The understanding that Wayne had never served, had gotten deferments during World War II to keep making movies, had played soldiers and heroes, while men like Michael had actually been soldiers and heroes, and that this fact had lived in Wayne’s chest like a stone for three decades. “Welcome home,” Wayne said.

Two words, that was all. But the way he said them, like he meant it, like he understood what those words cost to say and what they meant to hear. made Michael’s throat close up so tight he couldn’t respond. Wayne reached up and took off his hat. John Wayne, the Duke, icon of American masculinity and frontier mythology, standing bareheaded in the desert sun, hand in hand in front of a nobody extra who’d done what Wayne had only pretended to do in front of cameras.

“Thank you for your service,” Wayne said. “Formal, deliberate.” Each word waited. Michael nodded. Couldn’t speak. Tears cutting tracks through the dust on his face. And he didn’t even care who saw. Wayne held his hat in both hands. Looked at it. That battered Stson he’d worn in how many films? Property of the studio. Piece of costume.

Symbol of every character he’d played who’d been brave and strong and righteous. He held it out. I want you to have this. Michael stared. Sir, I can’t. You can. Wayne’s voice was gentle but absolute. I’ve worn a lot of hats and a lot of pictures. Pretended to be a lot of things. You were the real thing.

So, you take the hat. The assistant director finally found his voice. Duke, that’s that’s a costume piece we need it for. Get me another one, Wayne said, not looking away from Michael. This one’s retired. Subscribe and leave a comment because the most important part of this story is still unfolding. Michael took the hat. His hands shook.

The Stson was heavier than he expected, sweat stained, shaped by Wayne’s head over weeks of filming. Real, solid, more real than anything had felt in 8 months of being home. Sir, he managed to say, you don’t have to. I know I don’t have to, Wayne interrupted. But I’m going to tell you something, son. And I need you to hear it. I made 70

war pictures. 70. I played soldiers and marines and paratroopers and every kind of hero you can imagine. And every single one of them was pretend. I never served. Never went when my country called. stayed home and made movies while men like you went and did the real thing. His voice had dropped lower. The crew was still frozen watching.

The director had given up trying to get them back on schedule. This was more important than the schedule. I’ve carried that my whole life. Wayne continued, “Carried it like a weight. Every time I put on a uniform for a camera, every time I pretended to be brave, I thought about the men who were actually doing it. who were actually over there, who were coming home if they came home to people who didn’t understand, didn’t want to understand.

He gestured at the film set around them, the false front buildings, the carefully arranged props, the illusion of the old west constructed in the middle of the real west. This is all pretend, he said. All of it. But what you did, what you saw, that was real. And you deserve more than America’s given you. You deserve parades and medals and people thanking you every single day.

Instead, you’re standing here in a costume getting paid minimum wage to be background in my movie. Wayne’s jaw worked. That granite mask cracking just slightly. So, I can’t give you a parade. Can’t give you what you really deserve, but I can give you my hat. And I can tell you that every man on this crew, every single one respects what you did more than anything I’ve ever done in front of a camera.

You understand me? Michael nodded. Still couldn’t speak. Wayne put one hand on Michael’s shoulder. Heavy, solid. The weight of John Wayne’s hand on your shoulder. That meant something. Even if you knew it was just an actor, even if you knew the myth wasn’t real, the gesture was real, the moment was real, you keep that hat, Wayne said.

And when people ask you where you got it, and they will ask, you tell them John Wayne gave it to you. You tell them why. You tell them a marine who actually served deserved it more than an actor who just pretended. He stepped back, looked at the director. Get me a new hat. This man’s keeping this one, and I want him upgraded from Extra Today player. Pay him accordingly.

If the studio has a problem with that, tell them to bill my salary. The director nodded quickly. Absolutely, Duke. We’ll take care of it. Wayne looked back at Michael. You need anything, anything at all. You ask for me. Not my agent. Not the studio. Me personally. You understand? Yes, sir. Good. Wayne almost smiled. Almost.

Now, let’s get back to work. We’ve got a movie to make, even if it is all pretend. Away from the cameras, Wayne made a choice no one expected. That night, after shooting wrapped, Wayne didn’t go back to his trailer. He found Michael in the extra holding area, still wearing the costume, still holding the hat like he was afraid it might disappear.

“Come on,” Wayne said. “Buy you dinner.” They drove into the nearest town, 40 minutes of desert highway in Wayne’s personal vehicle, a beat up pickup truck that looked nothing like the luxury cars people probably imagined he drove. Michael in the passenger seat had on his lap, still half convinced this was all some kind of heatstroke hallucination.

Wayne took him to a local diner. Nothing fancy. Vinyl boos and coffee that tasted like it had been brewing since morning. They sat in a corner booth and Wayne ordered chicken fried steak for both of them without asking what Michael wanted. They ate in silence for the first 10 minutes.

Wayne working his way through his meal with the methodical patience of a man who’d learned not to waste food. Michael picking at his appetite still unreliable after months of trying to remember how to be hungry. Finally, Wayne spoke. How long you been back? 8 months. Sir, stop calling me sir. I’m not your co. I’m just an old actor who makes CBA pictures. Yes.

Yes. Michael caught himself. Okay. 8 months, Wayne repeated. And you working this job? They ain’t taking care of you? They’re trying. It’s complicated, Wayne grunted. It’s always complicated. Government’s real good at making simple things complicated. He took a drink of coffee. You have family? Parents in Ohio.

We don’t we don’t talk much since I got back. They don’t understand. It wasn’t a question. Michael nodded anyway. Nobody does, Wayne said. Unless they were there, and most of America wasn’t there. So, you come home and everyone wants you to be normal again. Slot right back and like nothing happened. Like you didn’t see what you saw.

Like you’re not carrying what you’re carrying. Michael looked up surprised. Wayne was staring at his coffee cup like it contained answers. I know. Oh, I don’t understand it either, Wayne continued. How could I? I stayed home, made pictures, got rich, got famous. While boys, kids, really, most of them younger than you, went over there and came back different, if they came back at all.

He looked at Michael directly. But I’m trying to understand. That’s all any of us can do who weren’t there. Try to understand. try to give you what you need, and if we can’t understand, at least we can shut up and listen instead of telling you how you should feel. They sat in silence again. The diner’s jukebox was playing something country.

Merl Haggard, maybe. The waitress refilled their coffee without asking. I killed people, Michael said suddenly, not looking at Wayne, looking at his hands. kids probably in villages. You can’t always tell. You just you do what you’re ordered and you come home and nobody wants to hear about it. Wayne sat quiet, listening, not offering platitudes, not pretending he had answers.

I know I can’t fix that, Wayne said finally. Can’t give you words that make it right. But I can tell you this. You did your duty. You went when called. You came home. That takes more courage than anything I’ve ever done. He reached into his jacket and pulled out a business card. Wrote a phone number on the back. That’s my private line.

You call it if things get dark. You call it if you need work. You call it if you just need someone to listen who won’t judge. He slid it across the table. I mean that. Michael took the card, put it in his wallet next to his discharge papers. Share and subscribe. Some stories deserve to be remembered. Michael Reese worked on three more John Wayne films. Wayne made sure of it.

When Michael struggled with nightmares, Wayne’s private line rang at 3:00 a.m. sometimes. Wayne always answered. The hat stayed with Michael for 43 years. When he died in 2015, his daughter donated it to the National Veterans Museum. It sits in a glass case now next to a card with a phone number and a simple placard.

Given by John Wayne to USMC Corporal Michael Ree, 1972, a reminder that some men wear costumes, others earn respect. Wayne never spoke about that day on set, but he never made another war movie. He said he’d done enough pretending. The real thing deserve better.