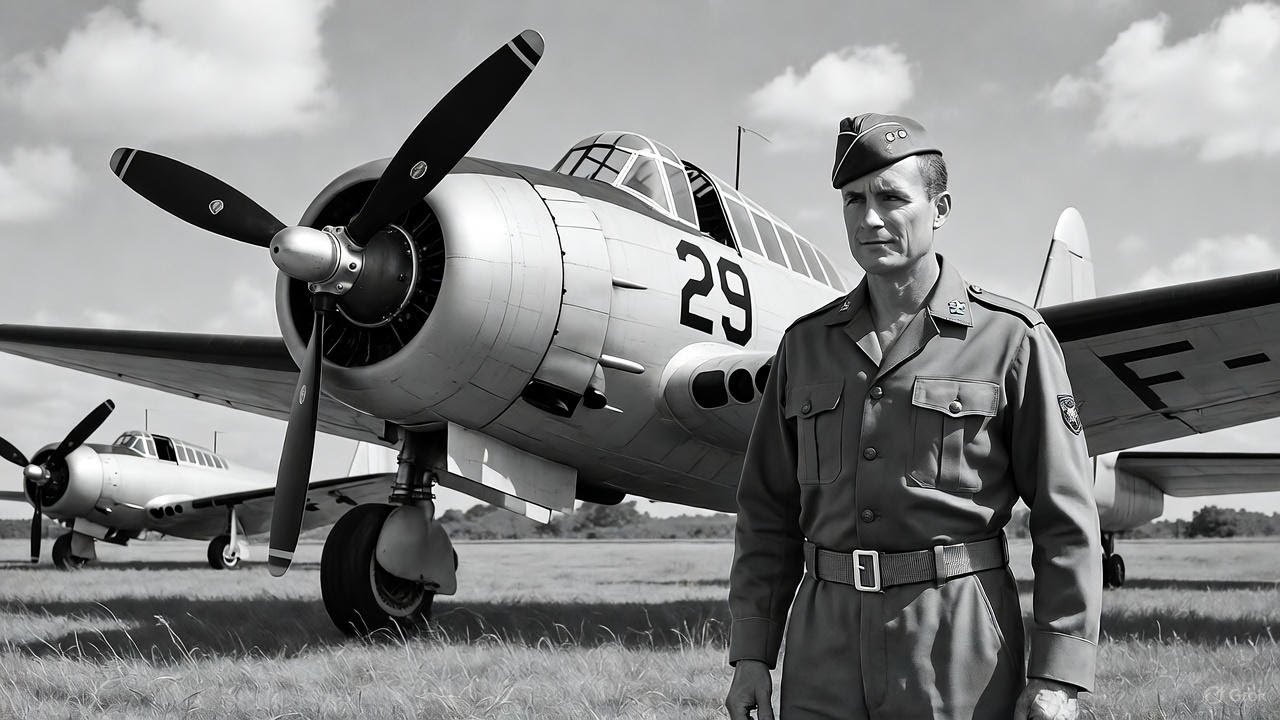

On September 16th, 1943 at Tokina airfield on Bugganville in the Solomon Islands, Captain James Sweat witnessed a devastating loss. His Wingman’s F4U Corsair fighter plane spiraled into the dense jungle trailing thick black smoke. The pilot’s final scream cut short over the radio. This marked the third aircraft VMF 213, the Hellhawk Squadron, had lost that week.

Shockingly, these losses weren’t due to superior Japanese fighters or mechanical breakdowns. They stem from wasted ammunition. Sweat’s own gun camera footage revealed the harsh reality. He had unleashed 400 rounds at a Japanese Zero fighter from 300 yd away. Tracers danced around the target, above, below, left, right, forming a deadly envelope that somehow missed the mark entirely.

The Zero escaped and scathed and Sweat’s guns ran dry. Just two minutes later, that same Zero downed his wingmen. Across Marine fighter squadrons in the South Pacific, the statistics were grim. Despite the Corsair’s superior speed and firepower, pilots achieved only a 3.2:1 kill ratio against Japanese planes.

The Corsair boasted 650 caliber Browning M2 machine guns with 3,000 rounds, allowing about 25 seconds of continuous fire. Yet, pilots were expending all their ammo for perhaps one hit in every 50 rounds. The core issue wasn’t pilot skill or gun reliability. It was gun harmonization. The point where bullets from all six guns converged.

Factory settings from VA aircraft specified convergence at 1,000 ft where bullets spread into a 30-foot circle. Japanese Zeros with their 29 ft wingspan were like threading a needle at 300 mph. The MF213 had the worst ammo to kill ratio in the Pacific. 890 rounds per confirmed enemy plane destroyed. At this pace, they deplete supplies before depleting the enemy.

Major Gregory Papy Boington visiting from VMF214 reviewed Sweat’s footage and remarked, “You’re shooting at ghosts. Your bullets are everywhere but on the enemy.” Unbeknownst to them, a 26-year-old aviation ordinance man, Staff Sergeant Michael Mickey McCarthy, was analyzing the same film in the maintenance tent. McCarthy, a high school dropout from South Boston who joined the Marines to escape the depression, handled ammo loading and gun maintenance, not design, but his insane modification would soon transform the Corsair into the Pacific’s deadliest

fighter. Gun convergence had plagued fighter pilots since World War I. Wing-mounted guns were angled inward to meet at a single point ahead of the plane. At that sweet spot, all bullets struck simultaneously for maximum devastation. The Corsair’s 1,000 ft factory setting was a compromise. It allowed time to aim and lead targets.

However, real combat exposed its flaws. Dog fights occurred at 200 to 400 yd where the bullet pattern widened to 20 ft, letting agile zeros slip through. Squadrons experimented. VMF124 tried 800 ft. VMF 214 attempted 600, but experts warned against anything below 500 ft, citing risks of gun barrel stress and wing damage.

Lieutenant Colonel William Millington’s August 1943 memo explicitly forbade it. Gun convergence below 500 ft exceeds safe structural limits. Pilots were ordered to engage at optimal range, essentially blaming their aim. But losses mounted. In September 1943, Marines lost 47 planes to enemy action with 78% tied to ammo exhaustion without fatal hits.

Japanese pilots exploited this weakness. Intercepted radio chatter from September 12th revealed. The Coroursers are fast, but their shooting is weak. Their bullets scatter like rain. Stay close when their guns empty attack. This baiting tactic prolonged the war, threatening the Solomon Islands campaign and island hopping strategy. General Roy Gger, commanding the first Marine aircraft wing, demanded solutions on September 14th.

We have the best planes and pilots, but we’re losing because we can’t hit targets. Enter McCarthy, an unlikely hero. Born in 1917, he learned mechanics in his father’s garage. As a sergeant in VMF213 for 8 months, he ensured flawless gun performance. But he saw patterns others missed, pouring over gun camera films and reports.

On September 17th, after Sweat’s failed engagement, McCarthy studied the Corsair’s manual on harmonization. He measured wing gun spacing 16 ft 3 in and calculated angles using basic trigonometry from his auto repair days. His epiphany convergence was too distant. At 1,000 ft, bullets took a second to reach targets during which a 300 mph zero moved 440 ft.

Pilots aimed at ghosts. At 300 ft, bullets arrived in one/ird of a second with the target shifting only 50 feet. Crucially, bullets converged into a dinner plate sized area. McCarthy crunched numbers. At 300 ft, the Corsair’s guns fired 4,000 rounds per minute, not 40,000, as exaggerated in excitement. concentrating devastating energy enough to shred a Zero’s 5,300lb frame with a 1 second burst of 80 rounds, delivering 40,000 ft-lb into six square ft.

Defying regulations, McCarthy acted without permission. On September 18th night, he and two crewmen, Corporal Eddie Wilkins and PFC Tommy Reyes, modified Sweatz Corsair, Bureau number 17883. They adjusted gun angles by two four degrees using bolts, reinforcing mounts with quarterin steel plates cut from scrap and welded crudely but effectively.

McCarthy built a wooden jig for alignment and bore sighted to a 300 ft target. By dawn, test firing into the ocean confirmed stability. No cracks. Sweat noticed the steeper gun angles that morning. McCarthy, what did you do? He demanded. adjusted to 300 f feet, sir. Sweat bocked at the illegality, but haunted by his wingman’s death, climbed in.

If it works, you’ll kill everything you look at. The test came swiftly at 0830 on September 19th for Corsair’s intercepted nine zeros and six valve bombers. Sweat Dove on a zero from 18,000 ft, closing to 320 yd before firing a 1second burst. The zero disintegrated, tails sheared, fuselage haved fuel exploding. He quickly downed two more with 200 rounds total.

Three kills in 45 seconds. The squadron claimed eight victories. Sweat got five, returning with 1,800 rounds left. Landing to a crowd, Major Wade Brit questioned McCarthy. Amid uproar from Millington sighting violations, Sweat interjected. I just downed five with 200 rounds. Pilots demanded modifications. Engineers protested. Brits silenced them.

McCarthy, modify every Corsair by morning. Defying Millington’s threats, he added. If it works, court marshall me. If not, the Japanese will kill us anyway. That night, McCarthy’s team harmonized all 22 flyable Corsairs. On September 20th, eight intercepted 12 zeros and eight Betty’s. Lieutenant Robert Hansen downed a Betty and zero in 15 seconds with 240 rounds.

The squadron achieved 15 kills, no losses, dropping ammo per killed to 180 rounds. Footage showed tracers as a solid beam causing instant explosions. Word spread. By late September, all Solomon squadrons adopted it. By October, every Pacific Corsair, the MF213’s kill ratio soared to 11.3 to1, ammo efficiency to 190 rounds per kill. Sweat down six zeros in 4 minutes on October 17.

Hansen ate in a day on November 11th. Capture Japanese testimony. Their bullets are a solid wall. If they point, you die. Intercepts warn avoid corsairs below 500 m from September 20th. To your end, Marines down 487 Japanese planes, losing 43 11.3 to1 ratio. Ammo efficiency rose 368%. Pilot deaths dropped from 4.7 to 1.2 weekly.

Boington tying a World War I record on January 3rd, 1944. credited McCarthy. It made me an ace. By February 1944, the Marine Corps standardized 300 ft convergence. Engineers tests praised McCarthy’s reinforcements, but the manual credited staff analysis, omitting his name. At VMF 213’s Christmas party, sweat toasted to Mickey McCarthy, the deadliest Marine who never pulled a trigger.

He estimated 800 lives saved. McCarthy received no formal recognition. Postwar, he returned to Boston, ran a garage, and downplayed his role. I loaded ammo. Nothing special. Sweat’s memoir honored him. McCarthy made us aces. Hansen’s letter echoed. He changed everything. McCarthy’s innovation influenced World War II fighters like the P-51 and postwar jets like the F-16.

He died in 1979 at 62. His obituary was brief. A 1987 plaque lists him. Modestly, yet his story endures. Innovation thrives from the ranks, courage in defying norms, and results overrank. McCarthy’s wrench won battles, proving one insane mod could rewrite aerial warfare.