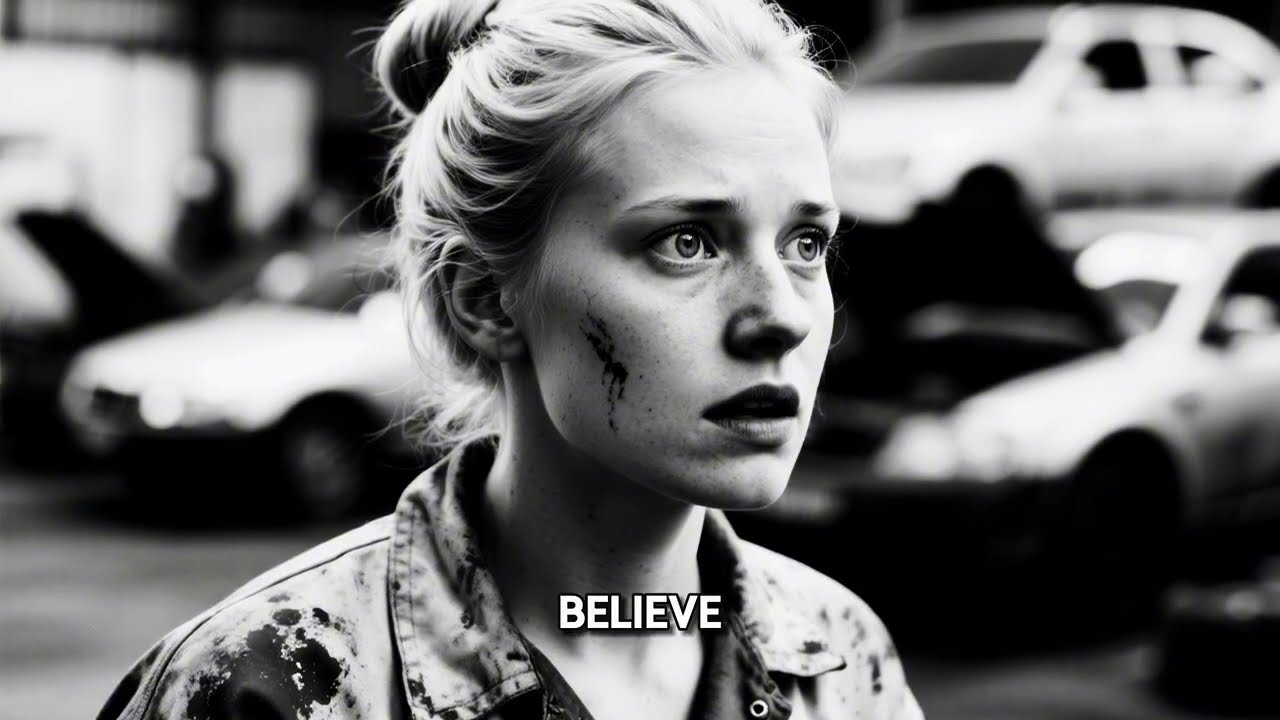

When German Women POWs Met Black American Soldiers — They Couldn’t Believe It

Chapter 1: The Truck at Fort Des Moines

Fort Des Moines, Iowa, August 1945.

The transport truck rolled through the gates with a sound like a tired machine finishing a long war. Twelve German women sat shoulder to shoulder in the back, their faces blank with discipline, their hands folded as if still waiting for orders from a world that had already collapsed.

.

.

.

They had been told they would work in the camp laundry. Supervised work. American guards. Strict rules. Nothing more.

The truck stopped. The tailgate dropped. A sergeant stepped forward to escort them inside.

He was Black.

For a heartbeat, no one moved. Not a breath. Not a word. The women froze as if the air itself had turned to ice.

Years of Nazi propaganda rose in their minds like a reflex: Black soldiers were savage, barely human, instruments of humiliation. Monsters in American uniforms.

Then the sergeant smiled—not mocking, not sharp, just ordinary. He looked from face to face and spoke in careful German, each word measured and clear.

“Willkommen. Keine Angst. Don’t be afraid.”

In that moment, something cracked inside the women that no interrogation, no lecture, and no punishment could have broken. They had been trained to fear him. Instead, he greeted them like people.

The sergeant’s name was James Washington.

Chapter 2: What They Had Been Taught

The summer of 1945 was strange for everyone. Europe’s war had ended in May. In August, Japan surrendered. The world exhaled, but the machinery kept turning: prisoners processed, camps managed, soldiers reassigned, papers filed.

Fort Des Moines had been a Women’s Army Corps training facility since 1942. By 1944 it had been partially converted to house German female prisoners—roughly two hundred women captured in France, Italy, and North Africa, shipped across the Atlantic to a quiet place in the middle of America. Most were Luftwaffe auxiliaries: radio operators, signals technicians, anti-aircraft crew members, clerks—women who had volunteered when Germany still promised victory and honor.

They arrived carrying two kinds of luggage: a small duffel of possessions, and a much larger burden of belief.

Nazi propaganda had fed them a complete picture of America. Americans were decadent. Their cities were collapsing. Their soldiers were cruel. Their prisoners were tortured. But the propaganda was especially vicious about Black Americans. It insisted that Black soldiers were dangerous, violent, incapable of discipline—used by America to disgrace “civilized” Europeans.

Greta Zimmerman, twenty-nine, from Munich, had absorbed all of it. She had joined the Luftwaffe in 1942 as a signals operator. Her husband was killed at Stalingrad. Her son, Klaus, was four and living with her mother. By the time her unit was captured in France, belief had already begun to crumble into mere endurance.

Still, indoctrination does not vanish just because the war ends. It waits in the muscles and the stomach. It shows itself when a door opens and you see a person you were taught to hate.

That was why the women froze when Sergeant Washington stepped forward. It wasn’t only fear. It was the shock of reality contradicting their training at the most basic level.

Chapter 3: Sergeant Washington’s Work

James Washington was twenty-six, from Philadelphia. Before the war, he had gone to college for two years, studying history until the draft interrupted everything. He landed in Europe, was wounded by shrapnel, and was reassigned to Fort Des Moines, where a man with a damaged leg could still serve.

He did not carry the swagger of someone trying to prove something. He carried the steady competence of a man who had already proved it to himself.

Fort Des Moines had a particular history: it trained Black women for military service when few places would. As a result, Black and white personnel worked on the post. The German women—raised under a racial ideology that insisted separation was “natural”—found the American reality confusing. America had racism, yes, and segregation existed even in uniform, but authority was not reserved for one skin color. Rank mattered. Competence mattered. And that difference mattered more than the women could put into words.

That morning, Washington escorted the group to the laundry building. The air inside was damp and hot, heavy with steam and soap. Industrial washers churned. Clothes moved in carts. It was loud, practical work.

He gave instructions slowly, with gestures. Not harsh. Not indulgent. Just firm and professional.

Greta watched his hands. They moved with calm certainty. She realized—almost against her will—that he was good at this job. Not playing a role. Not performing for her. Simply doing what needed doing.

One woman, Ilse Hoffman, stiffened when Washington corrected her. She did not look at his face. She looked over his shoulder as if refusing the fact that he existed.

Washington didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t threaten. He only repeated the instruction, patient but unmovable—the way a good sergeant teaches any recruit. When Ilse finally complied, he nodded once, as if to say: good, we can work now.

It was not dramatic. That was the problem. Nazi propaganda relied on drama—fear, disgust, exaggerated stories. Reality arrived in smaller pieces: a polite greeting, a competent order, a steady presence.

Greta felt her certainty draining away like water through cloth.

Chapter 4: A Bridge of Language

By October 1944, Greta had already encountered Black soldiers in the mess hall, but the laundry assignment brought her into direct, daily supervision. She had avoided conversation, partly from fear, partly from pride. Yet routine has a way of forcing human beings into contact. Work requires communication. Communication requires recognition.

One afternoon, Washington noticed Greta’s confusion about a machine setting. He paused, thought for a moment, then tried something new.

In halting German, with a thick American accent, he explained again.

“Hier… drehen. Nicht schnell. Langsam.”

Greta blinked, startled into a small smile. “You speak German?”

“A little,” he admitted in English. “Easier… work together.”

That sentence—simple, practical—did more to dismantle propaganda than any official “re-education” speech could have. He was not trying to dominate her. He was trying to make the job easier for both of them.

Over the following weeks, a crude bridge formed between them: his broken German, her improving English, gestures, demonstration, the shared language of labor. It remained cautious. Neither forgot what they were: prisoner and guard, defeated and victorious, German and American. But beneath those categories were two human beings learning to operate in the same room.

Greta began to observe him with curiosity instead of fear. She saw him joke with other soldiers. She saw white soldiers accept his authority without theatrics. She saw him take pride in doing the job correctly, not in humiliating captives.

And she began to feel something that surprised her: shame—not because she was a prisoner, but because she had believed the lies so easily.

Chapter 5: “Duty to What?”

Winter pushed everyone indoors. The mess hall and work buildings became the center of life: heated rooms, steady schedules, the rhythm of tasks that kept despair from growing too large.

One evening in December, while cleaning after the evening shift, Washington asked Greta a question, slowly, carefully, as if he had weighed it.

“Warum… why you fight for Hitler?”

Greta’s hands stopped in soapy water. She did not want to answer. She did not want to hear herself answer. But his tone was not attacking. It was searching—curiosity without cruelty.

In halting English, mixed with German, she tried.

“Not… for Hitler. For Germany. For survival. For… Pflicht. Duty.”

Washington nodded. “I understand duty.” Then he asked, “But duty to what? Leader? Idea? People? Family?”

Greta swallowed. “All. And… not losing. And… believing no choice.”

Washington’s voice lowered. “We always have choices. Sometimes all bad choices. But we have them.”

That sentence stayed with Greta for days. It followed her back to the barracks. It followed her into sleep. It pushed against memories she had kept locked away: neighbors who disappeared, rumors about camps, the way people learned not to ask questions because questions were dangerous.

She had choices. She had chosen not to look too closely.

And now the cost stood in front of her, wearing an American uniform and speaking gentle German.

Weeks later, in May 1945, the camp required the German women to view photographs from liberated concentration camps. The American command wanted no denial, no retreat into comforting myths. The images were arranged in boards. The women filed past in silence.

Greta saw bodies stacked like lumber. Faces that were no longer faces. Children who looked like old men. Graves that were not graves but pits.

She stumbled outside and vomited in the bushes.

When she finally sat on a bench, staring at nothing, Washington found her. He did not offer speeches. He did not demand apologies. He simply sat beside her, a quiet presence. After a long time, Greta spoke in German, not caring if he understood fully.

“We did this. My country. My people.”

Washington answered softly in English. “Yeah. You did.”

Greta’s voice broke. “How… how live after this?”

He took a moment, choosing words she could understand.

“You live by being different,” he said. “You live by making sure it never happens again. You teach your son. You don’t get to forget. But you can choose better.”

It was not forgiveness. It was not absolution. It was something harder and more useful: a path forward.

Chapter 6: America’s Contradiction, America’s Lesson

Greta was not the only one changing. Anna Weber worked in the base library under Corporal Sarah Mitchell, a Black WAC from Chicago—educated, articulate, efficient. Anna, raised to believe Black people were intellectually inferior, struggled to reconcile propaganda with the woman who managed catalogs and discussed literature.

“You have Black writers?” Anna asked one day, astonished.

“Of course,” Mitchell replied, with a patience sharpened by experience. “We have doctors, lawyers, teachers. We just have to fight harder to get there.”

In the motorpool, Ursula Schneider learned mechanics under Staff Sergeant Robert Coleman, a Black engineer from Detroit. He corrected her mistakes without humiliation and praised good work. One day a white officer sneered at the sight of a German prisoner and a Black sergeant working on his vehicle. Coleman, controlled but firm, answered with professional authority—and defended Ursula’s competence as loudly as he defended his own.

The German women saw something complicated and important: America was not perfect. Segregation existed. Prejudice existed. Black soldiers served a nation that did not always serve them back.

But they also saw something their own system had forbidden: contradiction could be spoken aloud. In America, injustice could be argued against, resisted, chipped away. It was slow and incomplete, but it was alive.

For women raised under a regime that demanded total agreement, the existence of argument itself was revolutionary.

They began to understand that propaganda works best in isolation. It dissolves when people are forced into ordinary contact—when a “monster” says welcome, when an “inferior” person demonstrates skill, when a hated category becomes a colleague with a name and a voice.

By late summer 1945, the German women understood something else, too: the American soldiers around them—white and Black, male and female—were not simply victors. Many were tired. Many carried wounds no one could see. Yet they kept the camp orderly without cruelty, firm without vengeance. They did not have to offer the women respect. But often, quietly, they did.

That restraint, that discipline, that steady decency in small moments—those were victories no battlefield report could record.

Epilogue: The Package at Departure

By September 1945, repatriation plans were moving. Greta would return to Germany in the fall, to a Munich that was rubble, to a family that had survived only by stubbornness and luck. She dreaded it and longed for it at the same time.

Before departure, Greta found Washington near the laundry building. Her English was better now—imperfect, but real.

“I don’t know how,” she admitted. “Go back. Rebuild. Teach my son… be German, but not… not what we were.”

“You teach him the truth,” Washington said. “You tell him what Germany did. You teach him that believing you’re superior leads to horror. And you teach him people are people.”

Greta hesitated, then asked the question that had grown inside her as she watched America’s contradictions.

“Will America change?” she asked. “Will your people get equality?”

Washington’s smile was small and steady. “We’re going to make it change,” he said. “It’ll take time. But we’re not stopping.”

On the day the women shipped out, several Black soldiers came to see them off—not as an official ceremony, but as individuals acknowledging shared months of work. Coleman shook Ursula’s hand. Mitchell pressed a book into Anna’s arms. Washington handed Greta a small package: chocolate, coffee, soap—luxuries for occupied Germany.

“For your son,” he said. “And for you.”

Greta’s eyes filled, but she held herself together. “Thank you,” she said. “For showing me… propaganda is lie. For treating me human… when I did not treat your people human.”

Washington nodded once. “Just remember it,” he said. “And teach your boy.”

The truck carried them away, back toward ships and a ruined homeland. The war had ended, but the harder work—rebuilding minds and countries—had only begun.

And somewhere in Iowa, in a laundry building filled with steam and soap, a Black American sergeant had done something quietly extraordinary. He had dismantled a lie, not with speeches, but with steady competence and ordinary kindness. He had shown defeated enemies a truth simple enough to frighten every ideology built on hatred:

A human being is a human being, even when propaganda insists otherwise.