Native American Elder Showed Me How To Find Bigfoot – Sasquatch Encounter Story

I never believed in Bigfoot until an elderly Native American man showed me how to find one. What I saw that night in Olympic National Forest changed everything I thought I knew about what exists in the deep wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. This is the story of how ancient tracking methods led me face to face with a creature that most people think is just a legend.

I work as a park maintenance worker in these woods, and I thought I knew them well, but I was completely wrong about what lies out there. My job isn’t glamorous, but I like it well enough. The pay is decent, and I get to spend my days outside instead of stuck in an office. Most days, I’m clearing trails, fixing wooden signs that hikers have carved their initials into, replacing broken fence posts, and doing general maintenance work.

During winter, I check for ice damage and make sure the trail markers are still visible, while in summer, I deal with erosion from heavy foot traffic. I’ve been doing this work for three years and thought I knew these woods inside and out. I’d memorized the layout of dozens of trails and knew which areas flooded in spring and which ridges got the worst wind in winter. The forest felt predictable to me, a place I could navigate with my eyes closed.

I’d seen all the usual wildlife you’d expect in a Pacific Northwest forest—black bears near the berry patches, elk herds during migration season, coyotes hunting at dusk, plenty of deer, even a few mountain lions from a safe distance. Once, I even saw a wolf slipping through the underbrush, though officially wolves aren’t supposed to be in this area anymore. The forest felt familiar to me, full of natural wonders, but nothing supernatural. Every sound had an explanation. Every track belonged to a known animal. Every strange sight turned out to be shadows or weather patterns.

Looking back now, I realize I was walking through that forest completely blind to what was really there, missing signs that were right in front of me the whole time. The tourist season always brings stories about Bigfoot sightings. People claim they saw something tall and hairy crossing a trail at dusk or heard strange howls at night that didn’t sound like any animal they recognized. Some report finding giant footprints in the mud or seeing trees twisted and broken in unnatural ways.

My co-workers and I would laugh about it over coffee in the ranger station, rolling our eyes at the latest sighting report. We figured people were just seeing bears standing on their hind legs or hearing elk calls echoing weirdly through the valleys. Maybe they were spotting deer shadows in the fog or letting their imaginations run wild after hearing too many campfire stories.

The Pacific Northwest has a whole industry built around Bigfoot tourism, and we assumed it was all just clever marketing designed to bring in tourist dollars. Gift shops sell Bigfoot keychains and T-shirts. Local restaurants have Bigfoot burgers on the menu. There’s even a Bigfoot museum a few towns over with plaster casts and grainy photos. We thought it was all entertainment, not reality—just a fun gimmick to make money off gullible tourists.

It was a Tuesday afternoon in late September when I finished up work near one of the main trailheads. The parking lot was mostly empty because it was a weekday, and the weather was turning cold. Summer was over, and the fall tourist season hadn’t really picked up yet. Just a few locals using the trails and nobody staying long. The sky was overcast and gray, typical Pacific Northwest weather where you can’t tell if it’s going to rain or just stay gloomy all day.

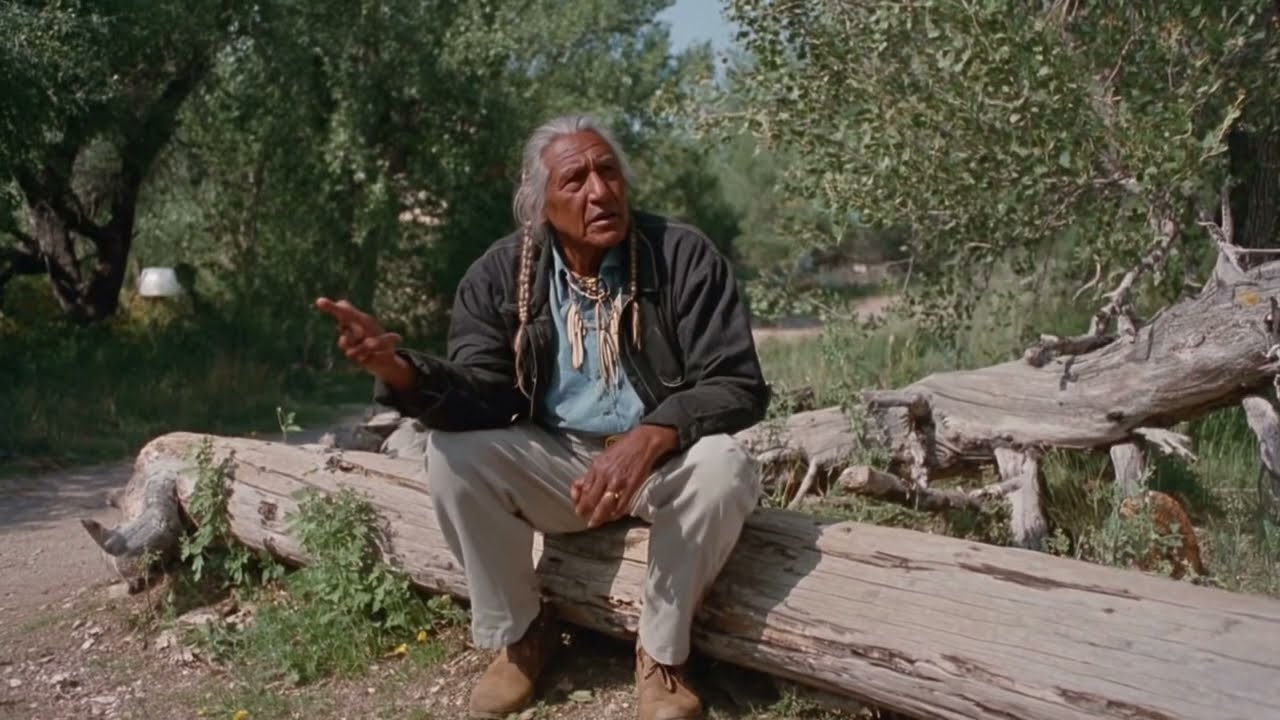

A cold wind started to pick up, rattling through the pine branches and carrying the smell of distant rain. As I loaded my tools into the truck, I noticed an old man sitting on a log bench near the trail entrance. The bench faces the forest, and hikers usually use it to rest before heading back to their cars. But this man didn’t look like he’d been hiking. He wasn’t dressed like a hiker at all—no fancy moisture-wicking fabrics or expensive boots, no water bottle clipped to his belt, no walking poles or backpack full of emergency supplies.

Just an elderly Native American man in worn jeans and a faded flannel shirt, sitting quietly and watching the forest with complete stillness. He had a simple walking stick across his lap, the kind you’d make yourself from a fallen branch, smoothed by years of use. Something about the way he sat there caught my attention. Most people fidget or check their phones or look around restlessly, but this man was perfectly still, just watching the trees like he was waiting for something specific.

I walked over to make sure he was okay because part of my job is checking on people who might be lost or in trouble. Sometimes older folks get tired on the trails and need help getting back to their cars. When I got closer, I could see he had deeply weathered skin from spending a lifetime outdoors—not the kind of tan you get from weekend hikes, but the permanent weathering of someone who lived outside. His long gray hair was tied back in a simple ponytail. Deep lines creased his face, especially around his eyes, like he’d spent years squinting into the sun and wind.

He was just sitting there with perfect posture, that walking stick across his lap, staring into the trees with an intensity that made me curious about what he was looking at. I asked if he needed anything or if he was lost, trying to sound friendly and helpful without being intrusive. He turned to look at me slowly, taking his time, and smiled. His eyes were sharp and clear, not confused or tired at all. There was an alertness in his gaze that surprised me, a kind of awareness that seemed to take in everything at once.

He said no, he was fine, just enjoying the quiet. Then he asked me a strange question that made my stomach do a little flip. He wanted to know if I’d ever seen the old ones in the forest. His exact words were, “Have you ever seen the old ones who live here?” I didn’t understand what he meant at first. Old ones. I thought maybe he was talking about old-growth trees, the ancient cedars and firs that have been standing for hundreds of years. Or maybe he meant old trails, the paths that indigenous people used long before this became a national park.

I must have looked confused because he saw it on my face. He clarified in a way that made my stomach turn. He asked if I’d ever seen the hairy people—the ones that walk like men but aren’t men, the ones that live deep in the forest where humans don’t usually go. I laughed nervously, more uncomfortable than amused. I told him about all the tourist Bigfoot stories we hear during summer. Trying to keep my tone light, I explained that people claim to see Bigfoot all the time around here, but it’s usually just bears or shadows or overactive imaginations working overtime.

I’d heard hundreds of these stories over three years and never believed any of them. They all sounded the same—vague descriptions of something tall and hairy glimpsed for just a moment before disappearing. His expression changed completely when I said that. The smile disappeared from his face, and his expression became serious, almost stern. The air between us seemed to shift, and I felt like I’d said something wrong, like I’d dismissed something important.

He told me his people had lived in these forests for thousands of years, long before it was a national park, long before the settlers came. They had always known about Bigfoot. His ancestors had seen them, tracked them, lived alongside them in these same forests for generations beyond counting. He said the Bigfoot were real and still here, still living in the remote valleys and deep wilderness areas where few people ventured.

Most people just didn’t know how to look for them properly. They looked with their eyes but not with their understanding, seeing only what they expected to see. His tone was completely matter-of-fact, like he was telling me it was going to rain tomorrow or that bears liked salmon. Just a simple statement of reality from his perspective. There was no excitement in his voice, no attempt to convince me—just calm certainty.

I asked if he was from one of the local tribes, and he nodded slowly. He mentioned which one but asked me not to share that detail publicly because some of the old knowledge was meant to be kept private within the community. Some stories weren’t for outsiders to spread around. I respected that request and told him I wouldn’t share it.

We talked for a few more minutes about the forest, about the weather turning cold, about how the trails were holding up after the summer traffic. I found myself genuinely curious despite my skepticism. There was something about the way he spoke, the absolute certainty in his voice that made me want to know more. He wasn’t trying to convince me of anything, wasn’t selling anything, wasn’t looking for attention. He was just stating what he knew to be true. Take it or leave it.

Before I left, he made an offer that surprised me. He said he could show me the signs if I was willing to learn. Most people walk through the forest completely blind to what’s around them, he said, but he could teach me to see what was really there. Not just trees and rocks and animals, but the other inhabitants of the forest—the ones that most people miss because they don’t know what to look for. I surprised myself by saying yes without really thinking about it.

Something in his calm confidence made me want to know what he knew, to see what he saw. We agreed to meet the next morning at dawn, and I drove home that night wondering what I’d just gotten myself into. Part of me felt foolish, like I’d just agreed to go on a Bigfoot hunt with a stranger. But another part of me was genuinely curious. What if there was something to all those stories? What if I’d been missing something obvious for three years?

I didn’t sleep well that night, my mind racing through possibilities. When my alarm went off before sunrise, I almost didn’t go, almost talked myself out of it. When I showed up at the trailhead before sunrise, he was already there waiting. The parking lot was empty except for my truck. No other vehicles around. He stood near the trail entrance in the pre-dawn darkness, perfectly still—a silhouette against the barely lightening sky.

He hadn’t brought any modern hiking gear, just his walking stick and a small leather pouch on his belt. I had my usual work pack with water, a first aid kit, my radio, protein bars—all the standard equipment. He looked at all my gear and shook his head slightly, a small smile playing at his lips. He didn’t say anything about my equipment, but I got the message that I was carrying too much.

We started walking into the forest as the sun began to rise. The light was soft and gray, filtering through the pine trees. Everything looked different in the dawn light, familiar trails taking on an unfamiliar quality. The morning air was cold and crisp, my breath visible in little clouds. He moved slowly but steadily, his walking stick tapping softly on the packed earth of the trail.

Every so often, he would stop completely and just stand there, looking and listening. The first lesson started about 20 minutes into our walk. He stopped next to a large fir tree and pointed to the branches without saying anything at first. I looked but didn’t see anything unusual—just branches like any other tree. Then he gestured for me to look closer.

I stepped up and examined the branches more carefully. Several of them were twisted in strange ways, bent and woven together at about seven feet off the ground—not broken by wind or bent by snow, but deliberately twisted like someone had grabbed them and tied them in knots. He explained that Bigfoot moves through the forest differently than other animals. Bears lumber and leave obvious paths, breaking branches and leaving claw marks on trees.

Elk travel in herds and make a lot of noise, bugling and crashing through the underbrush. But Bigfoot moves with purpose and intelligence, he said. They’re more careful about how they travel. These twisted branches are markers, ways a Bigfoot communicates with others of their kind—territorial boundaries or trail signs that only they understand.

We walked further, and he showed me more twisted branches at different heights. All too high for a bear to reach and too deliberate to be natural. Some were twisted clockwise, some counterclockwise, some were woven together in complex patterns that would have taken considerable time and dexterity to create. I tried to imagine what kind of creature could reach that high and have the hand coordination to twist branches like that.

It would have to be something with human-like hands, but much taller than any person. The thought made me uncomfortable but also fascinated. Then he led me to a small clearing about 50 yards off the main trail. In the center of the clearing were three structures—logs stacked in deliberate formations. Three thick logs arranged in a triangular teepee shape standing about five feet tall.

The logs were heavy Douglas fir, each one at least six inches in diameter and eight feet long. I tried to lift one end of a log and could barely budge it. Whatever had moved these logs into place had incredible strength. He said Bigfoot makes these structures all over the forest, though nobody knows exactly why. Maybe they’re territory markers, he suggested. Maybe they’re shelters for when it rains.

Maybe they’re teaching tools, ways that adult Bigfoot show young ones how to manipulate their environment. Or maybe they serve purposes we can’t even guess at because we’re not Bigfoot. He walked around the structure slowly, examining it from different angles. The logs showed no signs of tool marks, no saw cuts or axe marks. They’d been broken off trees by sheer force. Some still had bark on them and fresh sap oozing from the broken ends, suggesting the structure was relatively new.

The strangest lesson came next. He told me to close my eyes and just breathe in the forest air, to forget about seeing and just focus on smelling. I felt silly, but I did it anyway, closing my eyes and taking deep breaths. At first, I only smelled what I expected—pine needles and damp earth, the clean smell of morning forest. But then he took my arm and led me about 20 feet to the left, guiding me carefully so I wouldn’t trip. He told me to smell again, still keeping my eyes closed.

This time, there was something else underneath the pine and earth smells. A musky odor, thick and wild and pungent, stronger than any animal I had encountered in three years of working here. It wasn’t the smell of decomposition or rot. It was organic and alive, like the concentrated smell of a zoo, but wilder, more primal. It made my nose wrinkle and my instincts recoil slightly.

He said that was the smell of Bigfoot. Once you know it, you never forget it. And once you can identify it, you can tell when Bigfoot is nearby, even when you can’t see them. We met every morning for the next week before my work shift started. Each day, I learned to see the forest differently, noticing things I’d walked past a thousand times without registering.

He showed me what Bigfoot footprints look like in soft mud or snow. They’re massive, easily twice the size of human footprints, sometimes reaching 18 inches or more in length. Five toes clearly visible, arranged more like human toes than ape toes. The big toe isn’t opposable like a gorilla’s, but aligned with the others like a human foot. The interesting thing about the prints is how they sink deeper at the ball of the foot than at the heel.

Human footprints do the opposite, pressing deeper at the heel because we walk upright with our weight distributed differently. But Bigfoot walks slightly hunched forward, he explained, putting more weight on the front of the foot with each step. It’s a different gait than humans use, something in between human walking and ape locomotion. He showed me several old prints in dried mud along a creek bed, pointing out these details.

He pointed out scratches on tree bark that I’d never noticed before—long vertical gouges that started about seven or eight feet up the trunk and dragged downward, sometimes for three or four feet. The scratches were too high for a bear, and the pattern was wrong. Bears leave claw marks, but they’re horizontal or diagonal from climbing—four or five parallel lines from their claws. These marks were different—deeper and wider, like something tall had reached up and dragged its nails down the bark.

Maybe marking territory, he said, or maybe just scratching an itch. He explained that Bigfoot is most active at dawn and dusk, the times when light is transitional and most hikers are either just waking up or setting up camp. They avoid the middle of the day when trails are busy with people. They’re smart enough to know when humans are around, and they generally keep their distance, staying in the deep woods where people rarely venture.

That’s why sightings are so rare, he said—not because Bigfoot doesn’t exist, but because Bigfoot doesn’t want to be seen. They’ve survived this long by being incredibly good at avoiding humans. One morning, he taught me to listen for wood knocks. We were standing in a quiet section of forest when he picked up a heavy branch from the ground—a piece of deadfall oak about three feet long and thick as my wrist. He struck it hard against a tree trunk.

The sound echoed through the forest, a deep, resonant knock that seemed to carry forever, bouncing off the hills and valleys. It was completely different from a woodpecker’s rapid tapping or the sound of a hiker’s walking stick. This was deep and purposeful, unmistakably deliberate. He said Bigfoot uses sounds like this to communicate across long distances, across valleys where they can’t see each other.

If you hear wood knocks in a pattern—two or three knocks with pauses between them—that’s not a woodpecker or a hiker knocking snow off their boots. That’s Bigfoot talking to another Bigfoot somewhere out of sight. They might be coordinating a hunt or warning each other about human presence or just checking in on family members.

We stood there in silence for a few minutes after he made the knock, listening. Nothing answered, but I felt hyper-aware of every sound. He also taught me about habitat preferences and patterns of movement. Bigfoot likes to be near water sources, he explained—creeks and streams where they can drink and possibly fish, though he wasn’t sure if they actually fished or just scavenged dead fish.

They stay in thick cover where possible, dense forest where the canopy is heavy and the underbrush is tangled—places where visibility is limited and escape routes are plentiful. They’re drawn to areas with berry patches and fruit trees, places where food is concentrated and easy to gather without expending much energy. His grandfather had taught him all of this when he was a boy, and his grandfather had learned it from the generations before him. This knowledge had been passed down for longer than anyone could really measure, accumulating over centuries of living alongside Bigfoot in these forests.

It wasn’t book learning or theory. It was practical knowledge gained from direct observation over countless generations. I was being given access to something precious, something that most people would never even know existed. The weight of that wasn’t lost on me, even as I struggled with my skepticism.

On the eighth morning, he told me he wanted to show me something special. His tone was different that day, more serious, like we were graduating to a new level of understanding. We hiked deeper into the forest than we’d gone before, into a remote area I’d never patrolled for work. The trail was barely visible, overgrown with ferns and salal, clearly not maintained by the park service.

Moss covered everything, and the trees were enormous old growth, their trunks wider than my truck. We walked for over an hour, steadily descending into a valley I didn’t recognize. At the bottom of the valley was a creek, maybe 15 feet wide, running clear and cold over smooth stones. The water was that incredible blue-green color you only see in pristine mountain streams—so clear I could count individual pebbles on the bottom.

Massive cedars lined both banks, their roots exposed where the creek had eroded the soil. As soon as we got close to the water, I smelled it—that musky odor he taught me to recognize hanging in the air like an invisible presence. It was much stronger here than in the other locations we’d visited—so strong it was almost overwhelming.

The elder just nodded like he’d expected this and pointed to the muddy bank of the creek. I walked over carefully, my boots sinking slightly in the soft ground. There in the mud were footprints—huge footprints, at least 18 inches long and maybe 7 inches wide at the ball of the foot. They were fresh. I could see every detail. The individual toe impressions were clear, showing the pads, and even what looked like dermal ridges like you’d see on a human fingerprint.

The mud had squeezed up around the edges of the prints, meaning they were very recent. These weren’t old weathered tracks. My heart was pounding as I knelt down to look closer, my hands shaking slightly. Five toes just like he’d described, each one leaving a distinct impression. The depth of the prints suggested something incredibly heavy. I’m not a small guy—over 200 pounds—and my boots barely made an impression in that same mud. But these prints sank down almost two inches, suggesting whatever made them weighed 300 or 400 pounds at least.

I measured my boot against one of the prints. My size 11 boot looked like a child’s shoe next to it. The elder led me a little further along the creek bank. Following the tracks, they went right up to the water’s edge and then disappeared where the Bigfoot had apparently waded into the creek. On the opposite bank, I could see where the tracks emerged again, heading up into the dense forest.

He showed me a crude structure made from bent saplings and broken branches about 30 feet from the water. It looked almost like a lean-to but more complex, with branches woven together in a deliberate pattern. The structure was maybe five feet tall and six feet wide, providing partial shelter from rain. He said this was a Bigfoot shelter or marker, one of many scattered throughout their territory. They build these things and then move on, rarely using the same one twice.

Some researchers think they’re just for temporary shelter during rain. Others think they might be territorial markers or even teaching tools for young Bigfoot. Then he pointed to something on the ground near the water that I’d almost stepped in—scat, massive and unmistakably fresh. Steam was rising from it in the cold morning air, meaning whatever left it had been here very recently, maybe within the last hour.

I’m used to seeing bear droppings on the trails, and this was different in size and composition. It was easily three times the size of bear scat, filled with berry seeds I recognized as salmonberry and huckleberry. There were also bits of fish bones and possibly some small mammal fur. The elder said Bigfoot is omnivorous, eating whatever is available seasonally—berries, roots, fish, small animals, possibly even deer if they can catch one. They’re opportunistic feeders, intelligent enough to adapt their diet to what the environment provides.

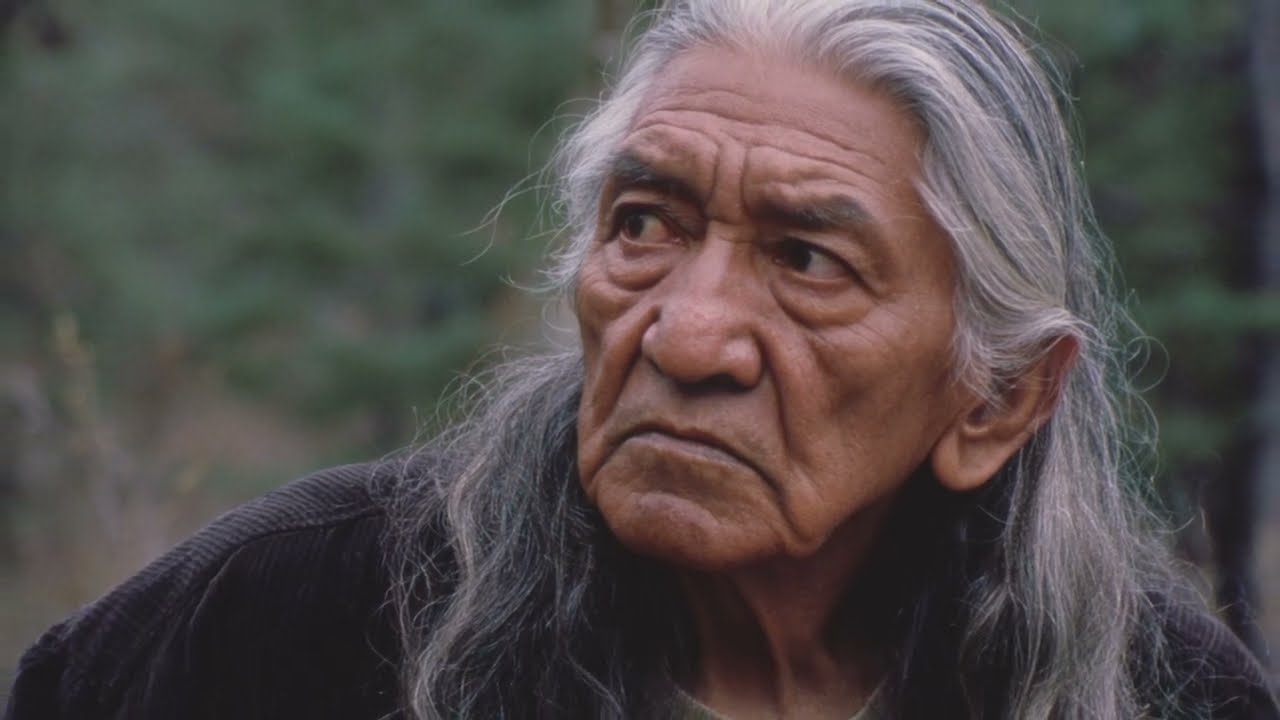

In that way, they’re more like humans than specialized eaters. He stood there looking around the area with deep satisfaction on his weathered face. He said they were still here, meaning Bigfoot still actively used this valley. You just had to know where to look and what to look for. Most people—even experienced hikers and park rangers like me—walk right past these signs without seeing them. They see the trees and the water and the wildlife, but they miss the bigger picture. They miss the evidence of something else living here, something that doesn’t want to be found.

We stood there for a long time, absorbing the reality of what we were seeing. As we hiked back toward the trailhead that morning, the elder got more serious with me than he’d been before. His tone shifted, and I could tell he was about to share something important. He told me that Bigfoot is usually peaceful and avoids confrontation with humans. In all the generations his people had lived alongside them, violent encounters were extremely rare.

But Bigfoot is fiercely protective of their territory and especially protective of their young. If you stumble into an area where a Bigfoot is living with young ones, or if you corner one accidentally with no escape route, things can get dangerous very quickly. The key is to always give them space to retreat. He emphasized, “Never chase them if you see one. Never try to corner them or follow them into thick brush. Never make them feel threatened or trapped. If you encounter one, stay calm, back away slowly, and give it room to leave. They’re not aggressive by nature, but they will defend themselves and their families if they feel they have no choice.”

He’d heard stories from other elders about people who got too close, who didn’t respect boundaries, and those encounters ended badly for the humans involved. He also warned me that Bigfoot is incredibly intelligent, more aware than any animal he’d ever encountered in decades of living in these forests. They can tell when they’re being watched. They can sense human intentions somehow, reading our body language or maybe even our emotional state in ways we don’t understand.

His people believed Bigfoot had a different kind of intelligence than humans—not better or worse, but different. They don’t build houses or use fire or make tools like we do. But they survive and thrive in an environment that would kill most humans in days. Sometimes Bigfoot will follow humans out of curiosity, he said—not out of aggression, but just to observe and understand. His grandfather had been followed several times while hunting in the deep woods. He’d hear footsteps matching his own pace, staying just out of sight in the trees. When he’d stop, the footsteps would stop. When he’d start walking again, they’d resume. When he’d intentionally change his pace, walking faster or slower, the footsteps would match the change.

The biggest mistake people make, he told me with emphasis, is trying to prove Bigfoot exists. They bring cameras and recording equipment and make a whole production out of searching for them. They crash through the forest in groups of five or ten people, talking loudly and shining flashlights everywhere, setting up cameras and motion sensors. Bigfoot avoids all of that. They’re smart enough to recognize human technology, and they associate it with danger. If you want to see one, you have to be patient, respectful, and quiet. You have to come to the forest on Bigfoot’s terms, not your own. You observe and respect. You don’t try to capture or prove anything. The moment you start thinking about proof, about convincing other people, you’ve already failed. Bigfoot will sense that energy and avoid you completely.

The next morning, I went back to that valley alone. The elder told me I was ready, that I’d learned enough to try observing on my own. I felt nervous but also excited, like I was about to take a test I’d studied hard for but wasn’t sure I could pass. I got to the creek area well before dawn, hiking in by the light of a dimming headlamp that I turned off as soon as I reached my destination.

I positioned myself downwind of the creek, tucked into a dense thicket of young hemlocks where I had a good view of the water but was mostly hidden from view. The thicket provided perfect cover, the branches hanging low enough that I could crouch underneath them. I brought nothing that made noise or light—no radio because even with the volume off, it occasionally beeped; no phone because the screen light would give me away; no watch because some watches beep on the hour. Just myself wearing dark clothes and a bottle of water that I’d opened beforehand so I wouldn’t have to break the seal later.

The elder had been very specific about this. Bigfoot associates human technology with danger. They might not understand what a phone or camera is exactly, but they know it means humans, and humans mean danger. I sat there in complete silence as the sun started to rise over the mountains. The forest woke up slowly around me. Birds began their morning song, starting with a few tentative chirps and building to a full chorus. Insects started buzzing and clicking. Squirrels began chattering in the trees.

The sounds built gradually, layer upon layer, until the forest felt fully alive. I waited and watched, barely moving except to slowly shift my weight when my leg started to cramp. I tried to be patient like the elder had taught me. Time seemed to move strangely when you’re sitting perfectly still. Minutes felt like hours. My mind wanted to wander, but I forced myself to stay focused, scanning the tree line, watching the creek, listening for any sound that seemed out of place.

Then I heard it—two sharp wood knocks echoing from somewhere across the valley, clear and unmistakable. Then silence. Then two more knocks, slightly different in pitch, like an answer from a different location. My skin prickled, and every hair on my body seemed to stand up. That was exactly what the elder had described—Bigfoot communication. The knocks had a deliberate pattern, not random, but purposeful. I stayed frozen, barely breathing.

My heart was pounding so hard I worried the Bigfoot might hear it. The musky smell started to drift in on the morning breeze, getting stronger with each passing minute. Something was moving closer to my position. I could feel it, even though I couldn’t see anything yet. The air felt charged somehow, electric with anticipation. Then I saw movement through the trees, maybe 200 yards away across the creek. Something large and dark walking upright between the pine trunks.

It was only visible for a few seconds at a time as it passed through gaps in the forest, appearing and disappearing behind trees. Too far to see clearly, but definitely walking on two legs. Definitely too tall to be a person—at least 7 or 8 feet tall from what I could judge at that distance. The way it moved was distinctive—not quite human, with a rolling gait that suggested immense power. I watched it move parallel to the creek on the far bank, heading deeper into the valley with clear purpose. It wasn’t wandering or foraging; it was going somewhere specific.

Then it disappeared into a thick stand of trees, and I didn’t see it again. I sat there for another hour, hoping it would come back, but the forest just returned to normal. The musky smell faded gradually. The birds resumed their normal patterns. The tension in the air dissipated. I hiked out feeling shaky and exhilarated at the same time, my legs weak and my hands trembling from the adrenaline.

I found the elder later that day at the same trailhead where we’d first met. He was sitting on that same log bench like he’d been waiting for me. I sat down next to him and told him what I’d seen. He listened carefully, asking specific questions about the wood knocks, about the smell, about the direction of movement. He nodded throughout my description, seeming pleased.

He said I was learning to see what had always been there, developing the eyes to perceive what most people miss. Then he made a suggestion that both excited and terrified me. If I wanted to see a Bigfoot up close, really see one clearly, I should try an overnight observation. He said, “Bigfoot is most comfortable at night, especially when the moon is bright enough to provide some visibility. They feel safer moving in darkness when most humans are asleep or huddled around campfires. Nighttime is their time when they can move more freely without fear of being seen.”

He gave me specific advice, speaking slowly and emphasizing each point. Bring no flashlight because the beam would scare them away instantly. Bring no camera because they somehow sense the electronics. Bring nothing that makes sound or light. Find a spot with good cover where I could see an open area, preferably near water where they’d be likely to visit. Set up during the day while I could still see, sleep during the afternoon and early evening to rest up, and then stay alert once full night fell.

He reminded me again to be respectful, not intrusive. I wasn’t there to prove anything to anyone else. I was there to observe for myself, to gain understanding, to see what few people ever see. The goal wasn’t evidence; it was experience.

I took a day off work the following week, calling in with a vague excuse about a family matter. I’d been thinking about it constantly since the elder’s suggestion. Part of me thought I was being ridiculous, wasting a vacation day chasing something that probably didn’t exist. But another part of me—a growing part—believed the elder completely. He had no reason to lie to me. He wasn’t trying to sell me anything or get anything from me. He was simply sharing knowledge that his people had accumulated over countless generations.

I checked the moon phase carefully and picked a night when the moon would be nearly full. I hiked into that valley in the afternoon, giving myself plenty of time to set up before dark. The forest looked different in the afternoon light, longer shadows and a golden quality to the air. I carried only essentials—a sleeping bag, but no tent because a tent would block my view and rustle with every movement. A tarp for ground cover to keep moisture out. Some cold food that wouldn’t need cooking because a fire would announce my presence for miles. Water in bottles I’d opened at home so I wouldn’t have to break seals in the night.

No fire, no technology, nothing that would announce my presence to anything with sharp senses. I found a dense thicket overlooking a small meadow near the creek. The spot was perfect, even better than my morning observation point. Dense evergreen branches gave me deep cover and shadow, but the view ahead was clear and unobstructed. The meadow was maybe 30 yards across, open grass with scattered wildflowers. The creek ran along the far edge, visible through a gap in the trees. If anything came to the water, I’d see it clearly in the moonlight.

I set up my simple camp, laying out the tarp and arranging my sleeping bag carefully. Everything was arranged so I could watch the meadow while remaining hidden. I ate a cold dinner of trail mix and jerky, chewing slowly and quietly, making no unnecessary sounds. Every small noise seemed amplified—the creek babbling over rocks, birds calling their evening songs, the wind rustling through pine branches. I was acutely aware of every sensation, every smell, every tiny movement in my peripheral vision. My nerves were strung tight with anticipation.

Then I tried to sleep as the sun went down, climbing into the sleeping bag while it was still light. The elder had told me to rest during the late afternoon and evening because I’d need to be alert all night. Bigfoot is most active in the deepest part of the night between 10 PM and 3 AM when most predators are sleeping and the forest is at its quietest.

It was hard to fall asleep knowing what I was planning to do. My mind kept racing through possibilities, through what-if scenarios. What if I actually saw one up close? What if it saw me? What if the elder was wrong and there was nothing out here? But eventually, exhaustion won over excitement, and I dozed off for a few hours of fitful dream-filled rest.

When I woke up, the moon was rising over the trees, enormous and orange on the horizon, gradually climbing and turning silver-white. The forest was bathed in pale silver light, bright enough to see fairly well but still maintaining deep shadows. I positioned myself in the thicket with a perfect view of the meadow. It took about 15 minutes for my night vision to fully develop. The meadow shifted gradually from murky shadows to a landscape of silver grass and black tree silhouettes.

The forest had a completely different quality at night, transformed into something almost alien. All the daytime sounds were replaced by the calls of owls hunting in the darkness, their hoots echoing through the valleys. Small nocturnal creatures rustled in the underbrush, mice or voles going about their nighttime foraging. The constant sound of the creek provided a soothing white noise that helped me focus.

I sat there perfectly still for hours. My legs cramped up badly, sharp pains shooting through my calves and thighs. My back ached from maintaining the same position. But I didn’t dare move. Even shifting my weight slightly might make noise that would carry through the quiet night. The mosquitoes were terrible, worse than I’d expected. They bit my neck and hands and face, landing silently and feeding before I even realized they were there. I couldn’t slap at them, couldn’t wave them away, just had to endure the itching and the constant tickle of their legs on my skin.

I focused on keeping my breathing slow and shallow, trying to become part of the landscape instead of an intruder in it. Around 11:00 PM, something changed. I’d been sitting there for almost three hours and had started to wonder if this whole thing was a waste of time. Maybe the Bigfoot only came through this area occasionally. Maybe I’d picked the wrong night or the wrong phase of the moon.

But then I noticed that all the normal forest sounds had suddenly stopped. Complete silence except for the creek. The owls stopped calling. The crickets stopped chirping. Even the small rustling sounds of mice and voles ceased completely. It was like someone had pressed a mute button on the entire forest. The silence was so profound it hurt my ears. The hair on the back of my neck stood up, and my heart started pounding hard enough that I could feel it in my throat.

Then I smelled it. That powerful musky odor, thick and heavy and unmistakable, drifting through the trees on the still night air. It was much stronger than I’d ever smelled it before—so strong it was almost overwhelming. The smell was concentrated and fresh, not old scent lingering from earlier. Something was close, very close, maybe within 50 feet of my position.

I heard heavy footfalls approaching from the forest side of the meadow—the sound of something massive moving through the underbrush with deliberate purpose. Small branches snapped with sharp cracks that echoed across the meadow. Dry leaves crunched under enormous weight, each step distinct and measured. The footsteps got closer and closer. My heart was pounding so hard I thought it might give me away.

Every instinct I had screamed at me to run, to get out of there. But I forced myself to stay frozen in place. A massive shape emerged from the tree line into the moonlit meadow. It was walking upright on two legs, easily 8 to 9 feet tall, covered in dark brown or black hair. Its shoulders were incredibly broad, much wider than any human, probably four feet across from shoulder to shoulder.

Its arms hung down past its knees, long and muscular, with visible definition even through the hair. The proportions were all wrong for a human—too tall and too broad. The face was flat in profile, not like an ape with a protruding snout. It had a pronounced brow ridge that cast deep shadows over the eyes and a flat nose that was more human than ape. The head seemed to sit directly on those massive shoulders with almost no neck visible, giving it a hunched appearance.

The Bigfoot moved with a slight forward hunch, walking in a rolling gait that was distinctly not human but not quite animal either—something in between, something unique. It moved with clear purpose across the meadow toward the creek, not looking around or acting nervous. Just walking like it owned this place because it did. This was its home, and I was the intruder—the one who should be afraid.

I watched every step it took, barely daring to breathe. The Bigfoot reached the creek and knelt down at the water’s edge. The movement was fluid and natural, not awkward like you’d expect from something so large. It cupped water in its hands, both hands together, forming a bowl, bringing the water to its mouth to drink.

The hands looked remarkably human in shape and proportion, five fingers on each hand, clearly visible in the moonlight. The fingers were thick and powerful but had the same basic structure as human fingers. I could see what looked like opposable thumbs used to cup the water more effectively. The Bigfoot drank for a long moment, cupping water several times and bringing it to its mouth.

Then it sat back on a large boulder near the creek bank—a rock about three feet tall that looked barely adequate to support such massive weight. The Bigfoot settled onto it like someone sitting down after a long walk, letting out a deep breath. The Bigfoot just sat there, apparently resting. Its massive chest rose and fell with slow, deep breaths. Each breath was visible in the cool night air, forming small clouds of vapor that caught the moonlight.

The Bigfoot made soft grunting sounds, low and guttural, almost like it was talking to itself or humming. Not words exactly, not any language I recognized, but some kind of vocalization that seemed purposeful rather than random. The sounds had a rhythm to them, rising and falling in pitch, almost musical in a strange way. It reminded me of how people sometimes talk to themselves when they’re alone, just making noise to fill the silence or working through thoughts out loud.

The Bigfoot seemed completely at ease, totally relaxed in its territory with no awareness that it was being watched. Then the Bigfoot reached down into the creek with one long arm extending far out over the water. Water dripped from its arm as it pulled out a rock from the stream bed—a smooth river stone about the size of a grapefruit. The Bigfoot held it up to look at it, turning it over in its hands like it was examining the texture or the color or the shape.

There was something curious about the gesture—something almost thoughtful, like the Bigfoot was studying the rock for reasons I couldn’t understand. Maybe it was looking for specific characteristics; maybe it was just enjoying the smooth texture. After maybe ten seconds, the Bigfoot tossed the rock aside with a casual flick of its wrist. The rock arced through the air, spinning, and landed in the creek with a loud splash that echoed across the meadow.

The Bigfoot watched where the rock landed, following its trajectory with its eyes. Then it picked up a stick from the ground near the boulder—a thick branch maybe three inches in diameter and four feet long. The branch was dead and dry, probably fallen from a tree years ago. The Bigfoot examined the stick for a moment, holding it in both hands. Then it snapped the stick in half with no apparent effort, like I might snap a pencil between my fingers.

The sound of the wood breaking was sharp and loud, echoing across the meadow like a gunshot. The Bigfoot didn’t even seem to strain, just applied pressure, and the thick branch broke cleanly in two. I flinched slightly at the noise, but the Bigfoot didn’t seem to notice or care. It looked at the two pieces for a moment and then tossed them aside casually.

The broken pieces landed in the grass with soft thuds. The Bigfoot went back to sitting quietly on the boulder, just being still. The whole scene was surreal beyond anything I’d experienced. Here was this creature that supposedly doesn’t exist, that science says can’t exist, just sitting by a creek in the moonlight, doing normal things.

It wasn’t doing anything particularly remarkable or supernatural—just existing in its own space, going about its nighttime routine. That ordinariness somehow made it more real, more believable than if it had been doing something dramatic. This wasn’t a monster or a legend or a figment of imagination. This was a living being with its own behaviors and patterns, resting after traveling, taking a drink, examining objects out of curiosity.

The Bigfoot sat there for maybe 20 minutes, just resting by the creek. I stayed perfectly still the entire time, even though my legs were screaming in pain from the cramped position. My back felt like it was going to spasm, but I didn’t dare move even a fraction of an inch. Then suddenly, the Bigfoot went completely still. Every muscle in its body tensed visibly even through the hair. Its head turned slowly, deliberately in my direction—not searching randomly, but turning directly toward my hiding spot like it knew exactly where I was.

My blood ran cold, and I felt a spike of pure fear. I realized with absolute certainty that it knew I was there. It had probably known the whole time from the moment it entered the meadow. Maybe it had smelled me despite my positioning downwind. Maybe it had heard my heartbeat or my breathing. Maybe it had some sense I didn’t understand.

Our eyes met across the distance of maybe 50 feet. Even in the shadows and moonlight, I could feel its gaze locked onto mine with laser intensity. It was the most intense moment of my life. I felt completely exposed, vulnerable, like all my clothes and my skin had been stripped away. I felt like I was being analyzed and studied, examined by an intelligence I couldn’t begin to understand. There was an awareness behind those eyes that was undeniable.

This wasn’t an animal staring at me with simple curiosity or assessing me as potential prey or threat. This was something thinking, considering, making conscious decisions about how to respond to my presence. The Bigfoot didn’t seem angry or afraid; it just seemed aware. It knew I was there, and it was choosing how to respond. It had options. It could charge and hurt me easily. It could flee into the forest and disappear. It could vocalize and try to scare me. But it chose none of those things.

It simply acknowledged my presence with that steady gaze, letting me know that it had seen me and assessed me. The weight of that intelligence was overwhelming. I felt like I was looking at something ancient and wise, something that had survived in these forests for countless generations.

The Bigfoot slowly stood up, still looking directly at me. It rose to its full height, towering and powerful in the moonlight, easily 8 ½ feet tall. Its shoulders were level with tree branches I couldn’t reach even jumping. Then it made a low huffing sound—a single deep exhalation from deep in its chest that wasn’t quite a growl but wasn’t friendly either. The sound was loud enough to feel in my chest like a bass note. It felt like acknowledgment, like the Bigfoot was saying, “I see you. I know you’re here. I’m choosing to leave, but I could choose differently.”

Then it turned and walked back toward the tree line with that same rolling gait I’d seen before. It didn’t hurry or run or show any sign of fear. It just walked calmly away, moving with unhurried confidence. Each step was measured and purposeful. It reached the edge of the forest and for a moment was silhouetted perfectly against the lighter background of the meadow.

Every detail of its massive form was visible. Then it stepped into the shadows under the trees and disappeared. One moment it was there, and the next it was gone, swallowed by the darkness under the canopy as if it had never existed. The forest sounds gradually returned after the Bigfoot left. Crickets started chirping again, tentatively, testing the air, and an owl called from somewhere distant. The normal night sounds resumed as if nothing had happened, as if the forest was releasing a breath it had been holding.

But I stayed frozen in place for another hour, shaking uncontrollably from adrenaline and awe. My legs were completely numb from staying still for so long. My whole body trembled and I couldn’t make it stop. I couldn’t quite process what I just witnessed. Every time I tried to think about it rationally, my mind just spun in circles.

I waited until dawn before moving, wanting to make absolutely sure the Bigfoot was gone and not coming back. As the sun rose gradually over the mountains, I finally stood up. My legs barely worked, and I had to grab onto a tree branch to keep from falling. Pins and needles shot through my feet and calves as blood flow returned. I walked carefully over to the creek where the Bigfoot had been sitting, moving slowly on unsteady legs.

The rock where it had sat was still slightly warm to the touch when I put my palm on it. The stone had retained the heat from the Bigfoot’s body even after an hour. I knelt down and looked at the muddy bank where there were clear impressions—massive footprints at least 18 inches long pressed deep into the soft ground. The prints were incredibly detailed in the morning light. I could see the individual toe pads, could see what looked like dermal ridges on the ball of the foot, could see how the mud had squeezed up around the edges from the immense weight.

I took out my water bottle and laid it next to one print for scale. The bottle was completely dwarfed. The print was almost as long as my forearm from elbow to fingertips. I found the broken stick pieces—the thick branch the Bigfoot had snapped like a twig. I picked up one piece and tried to break it further. I couldn’t even crack it—couldn’t even get it to splinter. Whatever strength the Bigfoot possessed was far beyond human capability, beyond anything natural.

I thought about the casual way it had snapped that branch. No visible effort, just a simple motion. The musky smell still lingered in the area, clinging to the grass and bushes near where the Bigfoot had emerged from the forest. It was weaker now, but still distinct, still recognizable. I gathered my sleeping bag and tarp, rolling them up with shaking hands. Part of me kept trying to rationalize what I’d seen to find some explanation that didn’t involve Bigfoot.

Maybe it was a person in a costume, though no costume could capture that fluidity of movement or produce that smell. Maybe it was a bear that had learned to walk upright, though no bear has hands like that or moves with that gait. Maybe I’d hallucinated the whole thing from lack of sleep and too much anticipation. But I knew none of those explanations made sense. I’d seen what I’d seen, and there was no explaining it away.

I hiked out of the valley on wobbly legs and went straight to find the elder. He was at the same trailhead where we had first met, sitting on that log bench like he had been waiting for me. I sat down heavily next to him and told him everything, every detail I could remember—the way it moved, the way it drank, the sounds it made, the way it looked at me.

He listened without interrupting, just nodding occasionally. His face showed no surprise, only deep understanding. When I finished, he was quiet for a long moment, looking out at the forest. Then he told me I’d been given a gift. “Most people never get that close to a Bigfoot,” he said. Most people spend their whole lives looking and never see one clearly or up close. The Bigfoot had let me see it.

It could have avoided me entirely if it wanted to. They’re masters of staying hidden when they choose to be, able to move through the forest like ghosts when they don’t want to be detected. But this one had chosen to let me observe it for an extended period. It had even made eye contact with me before leaving, which was significant. The fact that it made eye contact showed it was comfortable enough with my presence that it didn’t feel threatened—or at least not threatened enough to flee immediately or react aggressively.

I’d done everything right. I’d stayed quiet and still and respectful. I’d approached the forest on Bigfoot’s terms instead of demanding that Bigfoot accommodate my expectations. The Bigfoot had assessed me throughout the encounter, probably from the moment I entered the valley, and had decided I wasn’t a danger. That was the closest thing to acceptance I was likely to get from a wild Bigfoot.

I went back to my regular work routine after that, but everything felt different. I saw the forest with new eyes now, aware of what might be watching from the shadows. When I’m clearing trails or fixing signs, I catch myself looking for the signs the elder taught me—twisted branches, stacked logs, scratch marks on trees. I find them everywhere once you know what to look for. The forest is full of signs that I’ve been missing for three years.

Sometimes when I’m working in remote areas, I smell that musky odor on the wind and know a Bigfoot is nearby, probably watching me work from some hidden vantage point. I don’t try to find it or see it when that happens. I just acknowledge it quietly in my mind and continue with my work. The elder was right about respect being the key. I’m in their home, not the other way around.

I’ve never seen a Bigfoot that clearly again. I’ve caught occasional glimpses in the distance—dark shapes moving between trees, shadows that don’t quite match the light. I hear wood knocks sometimes echoing through the valleys in the early morning. That distinctive pattern of deliberate knocks, but I haven’t had another close encounter, and I’m okay with that. That one night by the creek was enough.

The elder and I still meet occasionally when our schedules align. He asks if I’ve seen anything new, and I tell him about my observations. He confirms or corrects my interpretations, continuing to teach me to read the forest. His people have always known about Bigfoot and have a different name for them in their language. To them, Bigfoot isn’t a mystery or a cryptid to be hunted and studied. They’re forest spirits or guardians—ancient beings that have always been part of the landscape.

They have intelligence and awareness that deserves respect, not exploitation. I still work in Olympic National Forest doing the same maintenance work I’ve always done. But now when I’m out there, I know what I’m looking for. I see the signs and acknowledge them. My co-workers still tell Bigfoot stories and laugh about tourists. I don’t join in anymore. Some knowledge isn’t meant to be shared with everyone.

The elder says that Bigfoot will reveal themselves to those who are ready—not ready in terms of equipment or location, but ready in terms of attitude. Ready to observe without trying to possess, ready to respect without trying to prove.

That’s my story. A Native American elder showed me how to find Bigfoot by teaching me to see the forest the way his people have always seen it—with awareness, respect, patience, and openness to mystery. Bigfoot is real, and I know that now with absolute certainty. But more importantly, I know that some things are meant to remain in the shadows, experienced by a fortunate few, and then left in peace.

If you catch a glimpse of something you can’t explain in the wilderness, remember what I learned. Don’t chase it. Just observe with respect and be grateful for the experience.