Police Officer’s Terrifying Encounter With Unknown Cryptid – Disturbing Encounter Story

The Call on County Road 17

Chapter 1: The RV at the Edge of the Trees

Some nights on duty blur together until they feel like copies of the same eight hours. Paperwork, traffic stops, noise complaints—repetition sanded down into routine.

And then there are the other nights.

.

.

.

The ones that tear a seam in how you see the world and never quite let it stitch closed again.

Three years ago, on an October shift, I answered a call that ended my career. Officially I left for “mental health reasons after a traumatic incident.” Unofficially, I saw something in the woods that shouldn’t exist and lost my partner to it.

I’d been a cop for eight years at that point. I’d done everything from wrestling drunk guys in bar parking lots to pulling bleeding teenagers out of twisted cars at three in the morning. I’d seen overdoses, suicides, the aftermath of people doing the worst things imaginable to each other.

I thought I had a handle on what this world contained.

It was a little after midnight. Me and my partner, Daniels, were cruising the quieter stretches of the county, the kind of roads that wind between fields and timber stands without ever touching a streetlight. The radio had been lazy all evening—one noise complaint, one welfare check, nothing serious.

Then dispatch crackled.

“Unit 12, copy a possible break‑in in progress, outskirts of jurisdiction. Caller reports someone trying to force entry into her RV. Address is—”

The dispatcher rattled off coordinates and a rural route number. I recognized the general area: the forest boundary where the county peters out into timber company land and land that doesn’t belong to anyone but the trees.

“Any further?” Daniels asked into the mic.

The dispatcher hesitated. I could almost hear her reading her notes.

“Caller sounded extremely distressed. Said someone was clawing at the door and calling for her to come out. She stated the voice ‘didn’t sound human.’ Call disconnected before we could get more.”

That phrase—didn’t sound human—hung in the cab like a bad smell.

Daniels and I exchanged that look cops get when something’s off. It might be drugs. It might be a psychotic break. It might be some bastard trying to terrify a vulnerable person in the middle of nowhere.

Or it might be worse.

“Unit 12 en route,” Daniels said. He flipped on the light bar, no siren, and turned us down County Road 17.

The houses thinned quickly. Porch lights disappeared behind stands of fir. The pavement narrowed and devolved into patched asphalt and broken edges. We passed the last mailbox—a rusted thing leaning at an angle—and then we were alone with trees pressing in on both sides.

The main road gave up entirely a couple miles later. Daniels turned off onto what the map called a “secondary access route” and what reality called a rutted dirt track. We crawled over potholes and washed‑out sections, high beams punching a narrow tunnel through the dark. Beyond that cone of light, the woods clung together, thick and silent in a way that made the hairs on my arms stand up.

Neither of us said much. We didn’t need to. The set of Daniels’ jaw, the way his hands held the wheel at ten‑and‑two a little tighter than usual, told me enough. We’d been to remote calls before—family disputes where the nearest backup was fifteen minutes out, standoffs that could go sideways fast. This felt different.

By the time we saw the RV, the silence had gone from quiet to oppressive.

We came around a bend and there it sat, fifty yards ahead, crouched at the edge of a treeline like it had tried to back away from the forest but hadn’t gotten far.

The door was wide open.

Warm yellow light spilled out onto the dirt, pooling in front of the steps. No movement inside. No shadows crossing that glowing rectangle. No figure stepping forward to wave us down.

We stopped the cruiser a good distance back, killed the light bar, and left the engine running. Habit. Insurance.

We approached on foot, hands on our holstered weapons, flashlights sweeping. “County Sheriff’s Office!” Daniels called out. “Ma’am, if you can hear me, call out! We’re here to help!”

No answer. Just that thick silence pressing in on the edges of the light.

The closer we got, the worse it looked.

The doorframe was shredded. Long, parallel gouges raked through metal and fiberglass, curling it back like torn paper. I’ve seen doors forced with crowbars, kicked in, shot off hinges. This was something else. The marks weren’t broad pries; they were narrow and deep, as if someone had dragged oversized claws down the frame again and again, trying to find purchase.

“We got an animal out here?” Daniels muttered.

“Bear?” I offered, though I didn’t buy it. Bears tear. They don’t scratch the same spot over and over until metal peels.

We drew our pistols and moved inside.

The RV was small. A kitchenette to the left. A little dinette. A narrow hall leading to the sleeping area in the back. We cleared it methodically, the way the academy teaches you—corners, cupboards, under the table. No sign of anyone.

What we did find turned my stomach.

The place had been wrecked. Cabinet doors hung open, contents spilled. Plates and cups lay shattered across the floor, glinting in the light like teeth. A picture of a smiling couple on a beach lay face down, the glass spider‑webbed.

Near the front door, a clear, viscous liquid pooled on the linoleum. It had the consistency of egg whites, thick and gelled, with threads stretching when my flashlight beam shifted over it. A smell came off it—sour, metallic, edged with rot. Like raw meat forgotten on a counter for days.

“What the hell is that?” Daniels asked.

“No idea,” I said. And I didn’t. It wasn’t blood. It wasn’t vomit. It wasn’t any bodily fluid I’d seen at a crime scene. I swept my beam around. There were a few other patches, on the wall near the door, smeared lower down as if something had leaned or slid.

The hallway to the bedroom was worse.

Drawers yawned open, their contents hurled across the small space—shirts, underwear, socks scattered like windblown leaves. But there was a pattern: the chaos looked frantic, but directional, like someone trying to grab specific items in a hurry and failing, hands shaking too much to be precise.

The bed was a mess. Sheets twisted and half‑dragged off the mattress, blankets knotted toward the edge, as if someone had been hauled toward the floor.

“Back door,” Daniels said quietly.

I followed his light to the rear exit I hadn’t noticed on the initial sweep. It stood open too, the screen door bent where it had been forced. Cold air breathed in through it, bringing with it the smell of damp earth and something else—a faint echo of that meat‑rot odor from the front.

Daniels stepped out first. “Oh, you’ve got to be kidding me,” he said, his voice going flat.

I joined him.

Behind the RV, the ground sloped gently toward the tree line. Recent rain had left it soft. In that mud, illuminated by our flashlights, a story had been written.

Drag marks. Long furrows of disturbed earth starting just beyond the RV’s back step and stretching toward the dark wall of trees thirty feet away. Between the two main grooves, smaller, irregular marks suggested heels, maybe hands, scraping futilely.

Beside the drag trails, impressions broke the mud in a staggered pattern. Not boot prints. Too long. Too narrow. Each ended in what looked like four or five small punctures, toe‑marks elongated into claw‑scores.

We didn’t say the word kidnapping. We didn’t have to.

Daniels keyed his shoulder mic. “Dispatch, 12. We have signs of forced entry and possible abduction. Victim may have been dragged into the woods. Requesting immediate backup and K‑9. Also advise Search and Rescue we may need them at first light.”

“Copy, 12,” dispatch said. “Nearest units are twenty minutes out.”

Twenty minutes.

In a town, that’s an eternity. In the woods, it’s worse.

I looked at the drag marks disappearing into the dark. Looked at the torn doorway. Thought about the quaver in that woman’s voice over the radio.

“We don’t wait,” I said.

Daniels grimaced. “Yeah. I know.”

We checked our flashlights, double‑checked our mags, and stepped into the trees.

Chapter 2: Bones in the Trees

The forest swallowed us fast.

Moonlight, such as it was, vanished under the canopy. The temperature seemed to drop ten degrees the moment we passed the first line of trunks. Our beams cut narrow tunnels through the blackness, revealing ferns and undergrowth and trunks spaced just irregularly enough to make straight lines meaningless.

For the first hundred yards or so, the trail was almost insultingly clear. The drag marks carved a continuous path through the damp earth, flattening leaves, snapping small branches. Here and there, a smear of that same clear, gelatinous substance from the RV glistened on the side of a sapling.

Then the ground turned stony and the story stopped.

We fanned our lights across the forest floor, looking for any sign—broken branches, scuffs, fabric caught on bark. Nothing obvious. Just rocks and roots and a carpet of needles.

“Split?” Daniels asked, knowing my answer before he said it.

“Negative,” I said. “We’re not playing horror movie.”

He snorted, but there was no humor in it.

We picked a direction based on what little we could see—branches bent downhill, leaves still trembling on shrubs, as if something large had moved that way not too long ago. As we walked, the trees seemed to lean closer together, their trunks not just vertical but warped, some twisting around each other, others bent at sharp angles like fingers broken and set wrong.

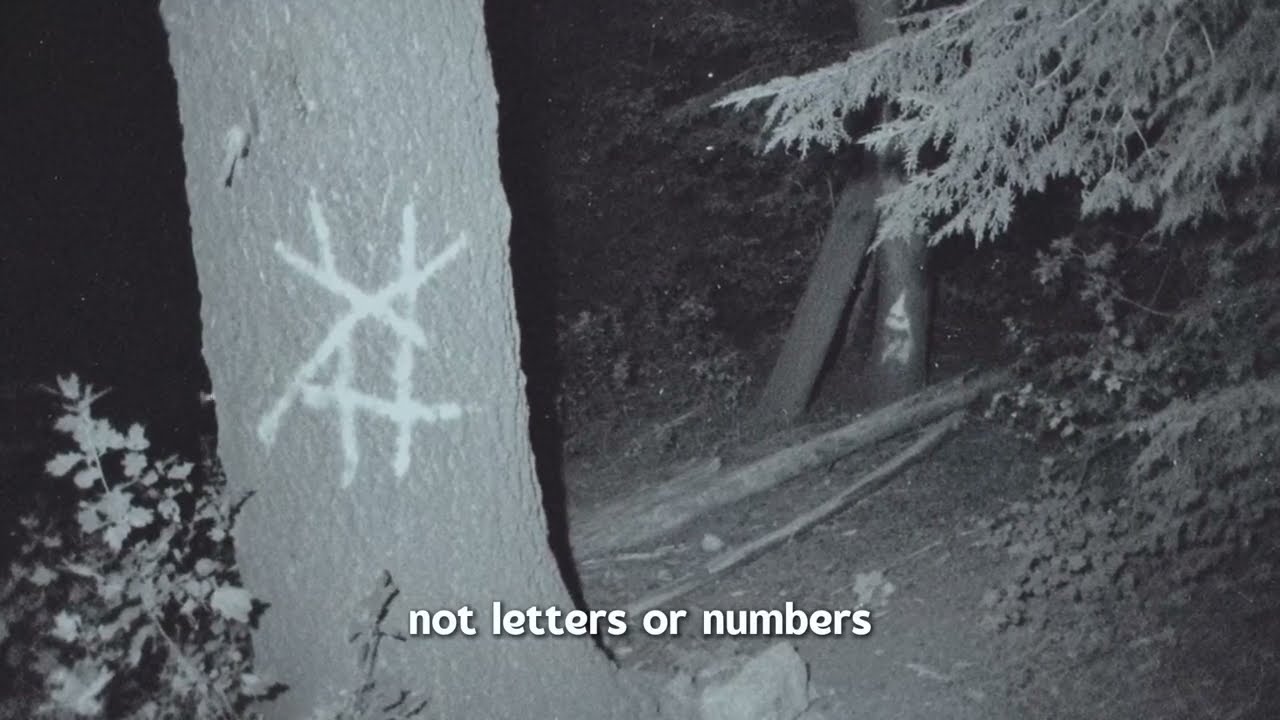

Our lights flicked over gouges in bark. Deep, parallel scratches clawed through outer layers into pale wood beneath. Some of the scars had grown over, dark cambium thickening the edges. Others oozed fresh sap that glistened black.

“Bears,” Daniels said, but his voice lacked conviction.

“Bears write in code now?” I asked.

Because some of the scars didn’t look like random scraping at all. They formed patterns: intersecting lines, repeated shapes, angular designs that felt too deliberate to be accidental. The longer I looked at them, the more my eyes ached. The lines refused to resolve into anything I recognized, but they made some primitive part of my brain want to look away.

We found the first bone on a flat rock about waist‑high, twenty feet off our guessed route.

It was small, maybe from a rabbit. Bleached white. Every scrap of tissue gone. No gnaw marks, no ragged edges. It had been cleaned with precision, the ends smooth and polished by something other than time.

It lay perfectly centered on the rock, angled just so.

“Coyote kill?” Daniels suggested, but even he sounded like he was testing the words more than believing them.

Coyotes don’t arrange trophies.

Twenty feet farther, another rock. Another bone. Bigger. Probably deer. Same treatment. Same careful placement.

We followed them—a breadcrumb trail made of skeletons.

The smell crept up on us as we walked. At first it was just a faint sourness under the ordinary forest scent of damp earth and leaf mold. Then it thickened into something cloying. Rot. Old blood. Meat gone sweet in the wrong way. Underneath that was a sharper note, almost chemical, that made my eyes prickle and my throat taste metallic.

We wrapped sleeves across our noses, but it didn’t do much. The odor seemed to seep into the air itself, into the bark of trees, into the soil.

And as we went deeper, the forest itself got wrong.

Trees bent at angles trees shouldn’t bend. Limbs sprouted from trunks at spirals that looked like they’d been guided into knots when they were saplings and then left to grow that way. Some had branches growing downward, dragging the ground like arms reaching toward something unseen.

Symbols carved into bark became more frequent. On one tree, an entire strip of bark from chest‑height up had been stripped away, leaving raw wood beneath. That wood was covered top to bottom in those same angular marks, cut so deep they should have killed the tree outright. Yet above, leaves rustled softly, green and living.

“Nature’s art project,” Daniels said weakly. “Real avant garde.”

He was scared. I could hear it under the forced lightness.

The whispers started as we passed that tree.

At first I thought it was wind. A faint susurration threading through leaves overhead. But the night was still. The air didn’t move. Yet the sound did, gliding from left to right to somewhere behind us.

We stopped and listened.

It wasn’t random. It had rhythm. Cadence. Like words.

Not English. Not Spanish. Not any language I’d heard in all my years on the job. But there was structure. Pauses. Repetitions. A rising lilt at certain points.

“Radio?” Daniels murmured.

I touched the mic on my shoulder. It was silent.

He lifted his flashlight toward the trees.

“Don’t,” I started to say. Too late.

Something moved thirty feet above us.

For a moment, I thought it was an owl hopping between branches. But it was too long. Too fluid. It flowed from limb to limb, pale against the dark, never shaking a leaf, never snapping a twig. Our beams sliced through gaps but never quite caught it. Every time the light swung toward where it had been, it was somewhere else—just outside the edges.

The whispers grew louder, overlapping. One voice turned into two, then four, then a dozen, all murmuring different threads in that same half‑language. Some were high, almost childish. Others were low, resonant. They came from above. From behind trunks. From what sounded disturbingly like beneath our feet.

My skin prickled with the instinctive knowledge that predators were very, very aware of us.

We pushed on because the alternative—turning back and admitting we’d left someone to die while we retreated to the safety of the road—felt worse. At least for the moment.

Clothes appeared next.

A T‑shirt hanging from a low branch, fabric stiff with age and dirt. A pair of jeans draped over a moss‑covered log. A jacket tied by its sleeves around a sapling, fluttering faintly in the motionless air.

At first we thought: campers. Kids screwing around. A weird campsite.

Then we found underwear. Socks. A single hiking boot with its laces neatly tied. A bra hung carefully on a twig, the way someone might drape it on a chair at home.

The garments were filthy, stained with mud and darker, older blotches. Some were sun‑bleached and frayed. Others still held their original colors. As we progressed, the number increased, hanging from branches at regular intervals like a grotesque collection.

We radioed our observations back to dispatch, our voices sounding small and tinny in the vastness.

Our signal crackled. “Copy,” came the reply, faint. “Backup still approximately fifteen minutes out.”

Fifteen minutes had never felt so long.

We kept going, following the fabric markers now as much as any physical trail. The whispers in the trees built to a chorus.

Then we heard water.

A narrow stream cut across our path, its surface oily, reflecting our beams in sickly rainbows. The smell here was nearly overpowering. I knelt at the edge, sweeping my light along the bank.

Hair floated along the margin, matted clumps snagged on rocks and roots. Not animal. Human hair. Dark and tangled. Scraps of cloth clung to the same obstacles—blue denim, flannel, something that might once have been bright pink.

Human footprints pressed the mud near the water—standard shoe sizes, treads we recognized from the city sidewalks. But as the prints continued along the bank, they elongated. The heel impressions thinned. Toes stretched and then sprouted little pockmarks at the front.

Morphing. As if whoever had walked there had started human and ended as something with claws.

The voices around us changed, too. Amid the alien syllables, I caught shards of English.

“Help—” “Please—” “Over here—”

But each word came out slightly wrong, the emphasis off, the vowels stretched.

I looked at Daniels. His face was pale under the brim of his hat.

“Maybe we wait for backup,” he said quietly.

“Ten more minutes,” I replied. “We go ten more, then we pull back.”

It was a compromise between duty and survival. It’s also the choice I wake up regretting most.

Chapter 3: The Girl in the White Shirt

The ridge rose ahead, steep but navigable, littered with loose rock and downed limbs. The trail of clothing led up it—socks, shirts, a baseball cap stuck on a broken branch like some forest scarecrow.

We climbed, breath loud in our own ears. The whispers fell away as we neared the top, replaced by something worse: silence. Not natural quiet, but an intentional hush, as though every living thing was holding its breath to see what would happen.

At the crest, the forest opened.

The clearing was about fifty feet across, a raw circle where nothing grew. No grass. No saplings. Just bare, blackened earth as if someone had held a fire there hot enough to kill the soil itself.

Bones ringed the edge.

Rib cages. Skulls. Long bones. Piled and tumbled like someone had tossed them there over years. Some were sun‑bleached and cracked. Others still bore scraps of tendon, darkened and dry. The sizes varied—deer, elk, smaller animals. But here and there, unmistakable shapes stood out: the curve of a human femur. The flat oval of a skull with eye sockets facing the sky.

“Jesus,” Daniels whispered.

In the center of the clearing sat a rough ring of stones, a fire pit of sorts. But instead of ash and charred wood, its basin was filled with that same clear, viscous fluid we’d seen in the RV. Under our beams, it seemed to move of its own accord, swirling in slow patterns that didn’t match any breeze, pooling and recoiling like something alive.

We took photos. Body cams rolled. My mind registered every detail, filing them away in the part of me that knew there would be reports and forensics and questions later.

Then, from beyond the far edge of the clearing, a voice called out.

“Help! Please—someone—help me!”

Female. Young. Terrified. Exactly how you’d expect a kidnapped woman to sound.

We moved toward it without thinking, weapons low but ready. The trees closed in again, branches weaving overhead to blot out the sky. The voice grew clearer as we approached, but there was something canned about it. The cries repeated in the same pattern, the same intonation, as if looping.

We stepped into a smaller clearing—twenty feet across, with a recently used camp in the center. Ashes in a fire ring still radiated heat. A ripped sleeping bag lay sprawled open. A backpack, partially unzipped, spilled trail mix and a water bottle.

“Hello?” Daniels called. “Sheriff’s Office. Where are you?”

The voice answered immediately, from just beyond the trees ahead.

“Over here! I’m hurt—please—”

It was closer now, and the imperfections were more obvious. The emphasis fell on the wrong syllables. Words ran together oddly.

I saw footprints in the soft earth—a tidy line of shoeprints leading toward where the voice was coming from. They were too evenly spaced. Every step the same distance. Every toe pointed dead straight. No scuffs. No slips.

Like someone had placed them deliberately.

“Stay sharp,” I muttered.

Movement at the treeline caught my eye.

She stepped out from behind an oak.

At first glance, she was the kind of young woman you might see in a college brochure. Mid‑twenties. Long dark hair framing a heart‑shaped face. Jeans and a white T‑shirt that clung to a slender frame. No visible injuries. No dirt. No leaves tangled in her hair.

In a forest that had tried to eat us alive, she looked as if she’d stepped out of a mall.

She saw us. Her eyes widened. Her mouth stretched into a huge, grateful smile.

Relief is a powerful drug. A part of me wanted to rush forward, to wrap her in a blanket, to walk her back to the RV and the flashing lights that were, by now, making their way up the county road.

But another part of me—the cold, suspicious cop part—stared harder.

Her eyes shone too brightly in our beams. Not just moisture. Reflectivity, like light bouncing off a mirror. The color was wrong, too. Not any shade of brown or blue or green I’d ever seen. Something pale and flat.

Her grin showed too many teeth. They were all a fraction too long, too even, each one a perfect match for its neighbor.

“Ma’am,” Daniels called, voice professional. “We’re officers with the Sheriff’s Office. Are you hurt? Did you make the call from the RV?”

She tilted her head as if considering the question. When she spoke, her voice matched the one from the woods almost perfectly. Almost.

“No,” she said. “That was my sister. She… she gets confused. Sometimes. She ran away.” She spread her hands in a helpless gesture. “I came to find her. To bring her home.”

The words themselves were reasonable. The delivery was not.

Her cadence was off. She paused in the wrong places, stressed odd words. Her voice had a hollow, echoing quality, like it had traveled down a long tunnel before reaching us.

And through it all, the smile never left her face.

I glanced at Daniels. The muscle in his cheek jumped. He didn’t like this.

“You alone out here?” he asked.

“Yes,” she replied. Too quickly.

“Where’s your vehicle?”

“Down there,” she said, gesturing vaguely back toward the way we’d come. “I parked by the big house.” The RV, presumably. But she didn’t say RV. Didn’t say trailer. Just “house,” like someone groping for the right word and missing.

Sight, sound, instinct—they all screamed that something was wrong. But she looked human. And she was, or claimed to be, connected to our original victim.

We couldn’t exactly tell her we thought she was… what? A luring entity? A mimic?

“There are more units on the way,” I said. “My partner will walk you back to the RV. We’ll get you somewhere warm, ask a few questions, then we’ll coordinate a full search for your sister. All right?”

She nodded, that same broad smile plastered on.

Daniels shot me a look. You sure?

I wasn’t. But procedure said get potential victims out of danger and into controlled environments as soon as possible. And somewhere out here, I still believed, a woman was possibly bleeding out under a tree.

“We’ll be right behind you,” I said.

Daniels holstered his weapon, put on his calm, reassuring voice, and stepped closer. “Ma’am, if you’ll come with me—”

She drifted toward him. I say drifted because her feet didn’t seem to connect with the ground properly. Her steps were too smooth, too gliding. The leaves and twigs under her didn’t crunch. Her jeans didn’t snag.

They disappeared between the trees, his flashlight beam bobbing ahead, her white shirt a ghostly blotch in the dark.

And I let them go.

Chapter 4: The Thing with Too Many Voices

The forest pressed in like a closing fist once they were gone.

I stood there for a few seconds, listening to the night swallow the last echoes of their departure. My own flashlight seemed dimmer now, the beam shorter. The weight of my own breathing in my ears felt too loud.

“Ten minutes,” I reminded myself. “Check another couple hundred yards, then backtrack. Backup should be on scene by then.”

I moved forward, following what I thought was still some kind of path—a line where the undergrowth was slightly less thick, where the ground bore those too‑perfect footprints in patches. The air felt heavy, like a storm might be gathering, but the sky, when I caught glimpses through gaps in branches, remained clear and blank.

For a while, the sounds around me were normal. An owl hooted in the distance. Something small skittered through the dry leaves. The faint hush of a breeze brushed high branches.

Then a low rumble rolled through the trees to my left.

It was a growl, but not like any dog or bear I’d heard. It carried a resonance that made my chest vibrate, a frequency that felt like it was under my hearing rather than in it.

I stopped. My hand found my pistol again.

The growl came again, a bit closer. Then, layered over it, voices.

Not whispers this time. Full volume. Human. Or mostly.

They came from ahead, a tangle of overlapping speech. Men’s voices. Women’s voices. High‑pitched child voices. All talking at once, out of sync, phrases crashing into each other. Some laughed. Some sobbed. Some pleaded.

“I’m here—” “Don’t—” “Help—please—” “Get back—” “I said I’m fine—” “Over this way—” “Why won’t you answer—”

The effect was overwhelming. It sounded less like a group and more like a radio caught between channels, picking up fragments from half a dozen transmissions at once.

My gut said: wrong.

I thumbed my radio. Static hissed back at me. No reassuring dispatch voice. No Daniels cracking some nervous joke. Just white noise.

I cut my flashlight and dropped into a crouch behind a fallen log, letting my eyes adjust to the dim blue‑gray of moonlight filtering through leaves.

The voices swelled, then dipped, wandering through the trees. Leaves swayed with no visible breeze. Something pale moved between trunks ahead, too large to be a human silhouette.

That pale thing stepped into a shaft of lunar light.

At least, some part of it did.

It was vaguely human in outline—two arms, two legs, a head atop shoulders. But the proportions were all off. It stood at least seven feet tall, its limbs too long and thin, joints bent at slightly wrong angles. Its skin shone dead white, almost luminous against the dark bark, and it lacked hair, clothes, anything that might break up that smooth expanse.

Its face—or where a face should have been—was wrong.

Features moved there, but not in the way features should. Eyes seemed to wander across it, sliding slightly as if trying to find a permanent position. A nose bulged and receded. A mouth stretched and shortened, never quite landing on a stable shape. It looked like clay in slow motion, constantly reshaped from within.

Its hands ended in claws—long, black, hooked things that gleamed like obsidian.

And every voice I’d heard came from that shifting mouth. They poured out of it all at once, a chorus. A woman sobbing. A man shouting. A child giggling. A teenager swearing. All layered together, all discordant, all emerging from the same throat.

It turned its head—and there was no question it saw me.

It paused, as if registering surprise or interest. Then a new expression slid over that unstable face. One I recognized despite the distortions.

A smile.

My training rode over my terror like a flimsy tarp in a hurricane, but it was something. I rolled up from behind the log, drawing my weapon in one fluid motion, muzzle up, sights aligning with the center of that too‑long torso.

“Police!” I shouted, because that’s what you shout, even when the thing you’re shouting at is clearly beyond caring. “Don’t move!”

It moved.

Not away. Toward.

Fast.

It came at a sideways angle, using trees as cover, its limbs bending and unbending with an unnatural elasticity. It didn’t run so much as pour through space, compressing and stretching, its feet barely seeming to touch the ground.

I fired.

The first three shots went center mass, years of muscle memory pulling the trigger in smooth succession. Muzzle flash lit the trunks for fractions of seconds. The thing jerked with each impact—tiny, involuntary movements that proved the rounds weren’t passing through stupidly or hitting phantom.

It didn’t fall.

Instead, it pivoted to my left, circling. Trying to get behind me.

The growl under the voices rose, low and satisfied. The chorus of human words scrambled, rearranging into new combinations. My name was in there, I think. Or maybe that was my imagination.

I moved with it, backing toward a thick oak, keeping the trunk at my spine so nothing could flank me completely. My shots became more desperate, trying to anticipate where it would be next. It blurred each time, slipping just out of the path of the bullet, its body seeming to smear from one position to the next.

The magazine ran dry. The slide locked open with a mechanical clack that sounded far too loud.

And then, just as suddenly as it had attacked, it withdrew.

It flowed backward into the trees, fading between trunks, its pallid surface catching the last of the light like a ghost sinking into deep water. The voices decrescendoed back into whispers, then into silence.

I stood there with an empty gun, my back pressed to rough bark, heart pounding so hard I could taste copper.

I don’t know how long I waited. Long enough for sweat to cool on my neck. Long enough for my hands to stop shaking enough that I could reload without dropping the magazine.

When I finally dared move my arm, I brought the radio up again.

“Dispatch, 12,” I said, my voice ragged. “Officer needs assistance. Unknown hostile in the woods. I repeat, unknown hostile. Where’s my backup?”

This time, blessedly, a voice crackled back.

“Unit 12, we’ve got three cars inbound to your location. ETA five minutes. Where’s your partner?”

“Supposed to be at the RV,” I said. “With a female we encountered. I’m heading back there now. Advise units to check the RV immediately.”

“Copy. Units 14 and 16, you copy that?”

Affirmatives chorused faintly.

I took a deep breath that felt like broken glass and started moving.

Chapter 5: Missing

The trip back felt longer than the trip in, even though I was retracing my own footprints.

Every tree looked suspect. Every patch of darkness felt thick enough to hide that pale, shifting thing. I kept my back to trunks whenever I could, scanning side to side, listening for the layered voices.

None came.

By the time I saw the glow of headlights through the trees, the tremor in my hands had mostly subsided, replaced by a numbness that felt almost worse.

Three cruisers sat in the dirt near the RV, light bars rotating lazily, casting red and blue reflections on bark and aluminum siding. A fourth, unmarked car had just arrived; Sergeant Miller was climbing out, tugging his belt into place.

They all looked whole and human and real in a way the forest no longer did.

One of the deputies, Ruiz, spotted me first.

“Jesus, you look like hell,” he said, hurrying over. “You okay? Where’s Daniels?”

“RV?” I asked, breathless. “He’s not there?”

Ruiz shook his head. “We swept it twice. Empty.”

Sergeant Miller strode over. “You’re bleeding,” he said, motioning to a scratch on my cheek I hadn’t noticed. “Where’s your partner, Officer?”

“He… he walked the female back here. I sent them together while I continued the search. She said she was the victim’s sister.” The words tasted worse as I said them, like ash in my mouth. “You’re saying they never made it?”

“Pull yourself together and tell me what happened,” Miller said. His tone was clipped, but not unkind. He had that command presence that seems to absorb panic, at least temporarily.

I told them.

Not everything. Not then. I said we’d found strange symbols carved into trees, signs of animal remains, possible evidence of multiple victims over time. I said we’d encountered a woman who claimed a missing sister. I said Daniels had escorted her back. I said I’d gone deeper, heard voices, been charged by something large that might be a person on drugs, or something else.

I didn’t mention the face that wouldn’t hold still. Or the hands like knives.

We spent the rest of the night and the following day searching.

By dawn, Search and Rescue had arrived. Dogs sniffed through the woods, tails high, then tucked, then refusing to go certain directions. A helicopter quartered the area from above, its blades chopping the air, thermal cameras scanning for heat signatures under the canopy.

We found more clothes. More bones. More of those slime‑filled stone circles. We mapped them. Photographed them. Flagged them with bright tape that looked obscene fluttering among the grays and browns.

We did not find Daniels.

We did not find the woman from the RV.

We did not find the dark‑haired girl in the white shirt with the too‑wide smile.

No blood trail. No signs of struggle near the path they would have taken. The drag marks from behind the RV ended at the tree line and then vanished into the same rocky ground that had swallowed our first trail.

The official investigation stretched on for weeks. Forensics teams analyzed the clear fluid and reported back nothing helpful: “Unknown organic composition with no clear match in existing databases.” The bones in the clearing belonged mostly to animals; the few human fragments were too degraded to yield DNA. The symbols carved into trees were logged, photographed, and filed under “possible occult activity,” though anyone who’s spent time in rural law enforcement will tell you that label gets tossed at anything weird in the woods.

They interviewed me again and again. So did Internal Affairs. So did a psychologist the department kept on retainer.

Each time, the story changed a little. Not in its core facts—that Daniels went into the forest with someone and never came out—but in the details I chose to share. The more I spoke about the thing I’d seen, the less believable I sounded, even to myself.

Eventually I learned to stop talking about the face.

The case file grew thick, then cold. Daniels’ status was changed from “missing” to “missing, presumed dead.” His wife held a funeral with an empty casket. We lined up in our dress blues, saluted the flag folded into a triangle, and tried not to think about how we were honoring someone whose bones might already be arranged on a rock somewhere under those trees.

I lasted six more months on patrol.

The first time I responded to a domestic in a farmhouse at night, my hands shook so badly on the wheel that I almost turned around. The first time a dispatcher sent us to check on a 911 hang‑up from a cabin outside town, I felt sweat on my back before we’d even pulled out of the station.

I stopped sleeping through the night. When I did sleep, I woke up with the echo of overlapping voices in my ears.

Desk duty came next. Then a leave of absence. Then resignation.

Chapter 6: Faces in the Dark

After I turned in my badge, I did what a lot of ex‑cops do. I tried to build a life that didn’t revolve around other people’s worst moments. I took a security job. I went to therapy. I drank more than I should have for a while. I stopped going out at night unless I had to.

I also started reading.

You’d be surprised, or maybe you wouldn’t, how many stories there are out there like mine.

Some are buried in internet forums where usernames are the only credentials. Some are in old casefiles you can only access if you know someone in a department and they’re willing to leave you alone in a records room “by accident.” Some are older still, passed down in whispers from one generation of hunters or rangers to the next.

The names vary.

Skinwalker. Wendigo. Fleshgate. Mimic. Not‑Deer. People talk about creatures that can steal voices, that can wear a human shape like a coat that doesn’t quite fit, that can call your name from the edge of the trees in the voice of someone you love.

They talk about teeth that are just a little too sharp. Feet that don’t quite leave prints. Eyes that reflect light like a cat’s, even when the face around them looks perfectly like your neighbor’s.

I don’t know how much of that folklore is rooted in something real and how much is our fear of the dark dressing itself up in stories. I’m a broken‑down cop, not an anthropologist.

But I know this: whatever I saw in those woods that night was trying to be human.

Not pretending flawlessly. Trying. It had learned how to shape some words. It had learned that we respond to certain sounds—“help,” “please”—and it used them. It had learned how to arrange bones and clothes in ways that would draw us deeper, past the point where backup could reach us in time.

The woman in the white shirt—if “woman” is even the right word—was better at it. She’d mastered a face, at least superficially. She knew how to smile and tilt her head and talk about “my sister” in ways that tugged on certain emotional strings. Her movements, though, her timing, her lack of dirt or injury in a place that chews up people who actually move through it—that gave her away.

And we still let her walk off with one of us.

The worst thought, the one that circles back at three in the morning, is this: what if the original 911 call wasn’t from a human woman at all?

Dispatch said she sounded frantic, terrified, described clawing at the door, a voice that “didn’t sound human” trying to lure her out. Then the call cut off.

What if that was the mimic practicing?

What if, by the time we got there, it had already taken whatever it needed from her—her voice, maybe her face—and the woman in the woods was the thing that had made that call, baiting us in with our own protocol?

I’ll never prove it. I don’t want to.

I don’t camp anymore. I don’t hike alone. I don’t answer calls from numbers I don’t recognize if I’m somewhere rural after dark. When I walk my dog at dusk and a stranger approaches on the sidewalk, there’s a small, irrational part of me that scrutinizes their smile, their gait, the brightness of their eyes.

If you’re looking for advice in any of this, here’s what little I can offer.

If you’re ever out in the woods at night and you hear a voice calling for help that sounds almost right, but not quite—if the timing feels too perfect, if the words repeat with the same cadence, like a recording—

Don’t answer.

If you meet someone out there whose clothes are cleaner than they should be, whose hands don’t have the scratches and dirt that moving through brush leaves, whose eyes shine a little too much in your headlamp—

Don’t go anywhere alone with them.

If you’re a cop, or a ranger, or any kind of first responder, and dispatch sends you to an isolated trailer or cabin with a report of a break‑in and “voices that don’t sound human,” take backup seriously. Follow protocol, sure, but don’t ignore the prickling on the back of your neck when something feels wrong.

Sometimes that feeling isn’t paranoia. It’s the tiny, ancient part of your brain that still remembers we haven’t always been alone at the top of the food chain.

Daniels’ case is technically still open. Every year or so, some new detective takes a run at it, digs through the reports, re‑interviews me, re‑visits the site with fresh eyes and ground‑penetrating radar.

They never find anything.

Maybe he died quickly. Maybe he’s buried in some narrow crevice the dogs can’t reach. Maybe the thing that took him just… unmade him.

Or maybe, and this is the one I try not to think about, it learned enough from him to walk down a road somewhere nearby wearing his face. Maybe it learned his laugh, his way of saying my last name, his habit of tapping the steering wheel when he drove. Maybe someone in another county met him on a trail and never knew.

I don’t look into those cases. I don’t go hunting for more stories, more proof. Not anymore.

There are things in those woods that are always watching, always learning. They’ve had centuries to refine the art of not being seen, and we’ve had maybe a few decades of telling ourselves that the only monsters are other people.

Maybe we’re both right.

Just remember this, if you take nothing else from what I’ve said: not every voice you hear in the dark belongs to a person. Not every face you see on a lonely road was born with the bones behind it.

And some calls are better left unanswered.