Nobody had ever walked out of a BBC audition midsong until four lads from Liverpool made the most powerful man in British radio question everything he knew about music. October 15th, 1963. BBC broadcasting house loomed over Portland Place like a fortress of British cultural authority. Inside its art deco walls, the empire of proper sound was controlled by men in tailored suits who decided what 20 million listeners would hear each week.

The light program, BBC’s popular music service, had the power to make or break careers with a single scheduling decision. On this crisp autumn afternoon, the building hummed with the efficiency of a welloiled machine. Producers moved through carpeted corridors carrying scripts for variety shows.

Engineers adjusted equipment in soundproof studios. Secretaries typed correspondents on official BBC letterhead. Everything operated according to rigid protocols established by men who believe British music should reflect British values, refinement, restraint, and respect for tradition. In studio B, Sir Reginald Peton adjusted his silk tie and checked his pocket watch.

As head producer for the light program’s popular music division, Peton wielded enormous influence over Britain’s musical landscape. Oxford educated, Sandhurst trained, and possessed of opinions as firm as his handshake. He had spent 15 years ensuring that BBC airwaves remained properly British kuners, brass bands, and carefully sanitized American imports.

Nothing too exciting, nothing too raw, nothing that might upset middle class sensibilities during afternoon tea. Today’s schedule included auditions for several new acts seeking coveted spots on Saturday Club, the BBC’s premier pop music program. Most applicants were predictable, cleancut young men performing acceptable versions of American hits, their regional accents carefully modulated to approximate BBC English.

safe choices for safe programming. The last audition of the day was listed simply as the Beatles Liverpool. Peton had agreed to the session reluctantly and only because George Martin at EMI had personally requested it. Martin was a gentleman. Cambridge educated like Peton himself, and his judgment in musical matters was generally sound.

But this request puzzled Peton. Four workingclass lads from Murzyside. What could they possibly offer sophisticated London audiences? At 3:47 p.m., a black cab pulled up outside Broadcasting House. Four young men emerged, their cheap suits wrinkled from the train journey from Liverpool. John Lennon, 23, carried a battered guitar case and wore an expression of barely contained skepticism.

Paul McCartney, 21, adjusted his tie nervously while scanning the imposing building facade. George Harrison, 20, stayed close to his companions, his dark eyes taking in details with quiet intensity. Ringo Star, 23, drumed his fingers against his leg in rhythm only he could hear. They had traveled overnight from Liverpool, sleeping fitfully in secondass compartments, while the train carried them toward what might be their biggest opportunity yet.

John had stared out the window for hours, watching the English countryside roll past in the darkness, thinking about his father, who had walked out when Jon was five, about his mother, Julia, who had died when he was 17. Music was the only thing that made sense of the chaos. Paul had dozed against George’s shoulder, dreaming of his own mother, Mary, dead from breast cancer when Paul was just 14.

He carried her memory in every melody he wrote, every harmony he sang. George, the youngest, had practiced chord changes silently on his lap, his fingers moving across invisible frets. At 20, he was already tired of being dismissed as just a kid by industry executives who couldn’t hear past his age to recognize his talent.

Ringo had kept time against the train’s rhythm, his drumsticks tapping quietly against his leg. He had joined the Beatles only a year ago, replacing Pete Best, and still felt the weight of proving he belonged with these three extraordinary musicians who had grown up together. The Cavern Club crowds loved them. But London was different.

London was where careers were decided by men who spoke with posh accents and wore university ties. London was where working-class boys like them were tolerated, not celebrated. London was where dreams either came true or died in rooms exactly like the one they were about to enter. The receptionist’s smile was politely distant as she directed them to a waiting area outside Studio B.

Four chairs arranged against a wall beneath a portrait of Lord Wreath, the BBC’s founding director general. The Beatles sat in uncomfortable silence, listening to muffled conversations from behind closed doors. Occasionally well-dressed men emerge from various offices, their voices carrying the authority of Oxbridge educations and inherited positions.

Bit different from the cavern, isn’t it? John muttered, his Liverpool accent seeming thicker in these refined surroundings. Paul shifted in his chair, acutely aware that their suits, purchased from secondhand shops and carefully pressed for this occasion, [snorts] looked shabby compared to the tailored elegance surrounding them.

At 4:15 p.m., voices drifted from Studio B’s slightly a jar door. Sir Reginald Peton was discussing the afternoon schedule with his assistant producer, a younger man whose eagerness to please was evident in every response. “After the brass quartet, we’ve got those Mury side boys,” Peton was saying, his voice carrying the casual dismissiveness of someone discussing a minor inconvenience.

George Martin specifically requested we hear them, though I can’t imagine why. Four workingclass lads with guitars. Rather predictable, isn’t it? The assistant producers laugh was appropriately appreciative. Shall I allow them the full 15 minutes, sir? Good heavens, no. 5 minutes should suffice. Let them play their little song, then we’ll bring in someone properly trained.

We’ve got standards to maintain. Of course, sir. These provincial acts rarely understand sophisticated London audiences anyway. Precisely. Still, we owe George Martin the courtesy. Give them their moment, then we’ll get back to serious business. The four Beatles exchanged glances. They had heard every word.

The casual contempt, the assumption that they were just another provincial novelty act, the certainty that 5 minutes was generous for boys from their background. Paul felt his face flushed with embarrassment and anger. He thought about his father’s warnings that music was no career for working-class lads, that he should have stayed in school, gotten a proper job.

George’s jaw tightened as memories flooded back of condescending school teachers who had dismissed his musical interests as unrealistic fantasies. Ringo looked down at his hands, remembering every time someone had suggested he wasn’t good enough for the other three, that he was just the drummer they’d settled for.

But Jon’s reaction was different. Something shifted behind those wire- rimmed glasses. Not hurt, but determination. He had heard this tone before. From authority figures who assumed that workingclass boys like him were destined for mediocrity. From teachers who had written him off as a troublemaker, from record executives who had suggested he might have more success with a different image, a different accent, a different everything.

Each dismissal had only strengthened his resolve to prove them wrong. Provincial axe, Jon repeated quietly, savoring the phrase, “Rough diamonds, cheap guitars.” He looked at his bandmates with a grin that his friends recognized as dangerous. “Well, lads, sounds like they’ve got us all figured out. 5 minutes,” Paul said, his voice tight with controlled anger.

“They think 5 minutes is generous. Then we’d better make sure it’s the most important five minutes of their bloody lives, John replied. Well, lads, John said quietly, his voice carrying an edge his bandmates recognized. Looks like we’ve got 5 minutes to change everything. At 4:25 p.m., they were summoned into Studio B.

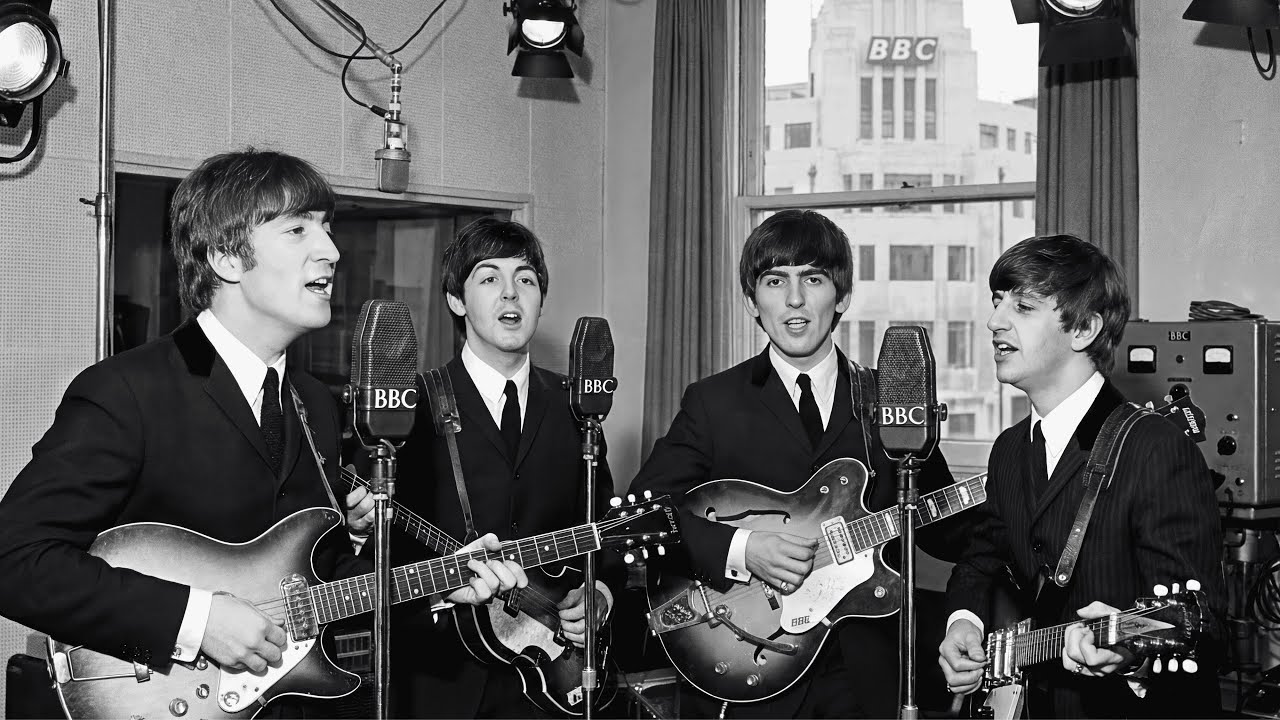

The room was larger than anything at Abbey Road with BBC microphones positioned precisely and mixing equipment that represented the pinnacle of British broadcasting technology. Sir Reginald Petan sat behind a control room window, his expression politely skeptical. Several other BBC executives occupied chairs nearby, their attention casual, distracted.

“Gentlemen,” Petton’s voice crackled through the studio monitors, his BBC English accent emphasizing the social distance between them. “You have 5 minutes to demonstrate your abilities. Please proceed when ready.” The Beatles positioned themselves around the microphones. No elaborate setup, no special lighting, just four young men with their instruments in a sterile BBC studio.

John stepped to the lead microphone, his guitar hanging from a strap that had seen better days. Paul moved to his left, bass guitar ready. George positioned himself stage right, his Gretch reflecting the fluorescent lights. Ringo settled behind the drum kit, his sticks poised. For a moment, the studio was silent.

Then John spoke into the microphone, his Liverpool accent unm modulated, unashamed. We’d like to play something for you. It’s called Love Me Do. But what emerged from the studio monitors was not the simple pop song the BBC executives expected. John’s harmonica cut through the air with a sound that was raw, honest, working class.

When the vocals began, it wasn’t the polished crewing that dominated British radio. It was something entirely different. Four voices that had learned to harmonize in church basements and youth clubs. Voices that carried the salt air of the Murzy and the defiant optimism of young men who refused to apologize for their origins.

Paul’s baseline drove the song forward with an urgency that made sitting still impossible. George’s guitar work was clean but edged, creating spaces for J’s vocals to soar and dive. Ringo’s drumming was not the restrained timekeeping that characterized British pop, but something that pulsed with life, with street energy, with the rhythm of a generation ready to announce itself.

But it was more than the music. The Beatles moved as they played, their bodies responding to rhythms that seemed to come from somewhere deeper than training or technique. Jon swayed slightly at the microphone, his eyes closed during the harmonica solo, completely lost in the moment. This wasn’t performance. This was communion with something larger than himself.

Paul’s fingers danced across his bass strings with a precision that spoke of countless hours in his father’s front room, practicing until his fingertips bled, driven by a need to create something beautiful in a world that often felt ugly. George’s face showed the intense concentration he brought to every guitar line. his left hand finding chord positions that created colors and textures most guitarists his age couldn’t even imagine.

Ringo leaned into his drums, his whole body becoming part of the rhythm section. Every beat placed with the confidence of someone who understood that the drummer’s job was to make everyone else sound better. They sang to each other, harmonized with an instinctive understanding that spoke of countless hours practicing in small rooms, dreaming of moments exactly like this one.

When Paul sang lead vocals on the bridge, John and George’s harmonies wrapped around his voice like musical silk. When John took the verses, the others provided a foundation that lifted his voice higher than it could go alone. This was the sound of four friends who had learned to think as one mind, to breathe as one voice, to become something greater than the sum of their individual talents.

In the control room, conversation stopped mid-sentence. Sir Reginald Peton, who had been shuffling through papers, found himself looking up, his pen forgotten in his hand. His assistant producer, who had been making notes about scheduling, sat down his clipboard and stared at the studio window. The other executives who had been chatting about weekend plans, turned their attention to the monitors with expressions of growing amazement.

One of them, a veteran BBC producer who had worked with every major British recording artist of the past decade, leaned forward in his chair and whispered, “Good God, what is that?” Another executive reached for his telephone, then stopped, realizing he had no idea who he should call or what he should tell them.

This was not what they had expected from four working-class boys from Liverpool. This was not simple imitation of American rock and roll or timid attempts at respectability. This was something authentically British yet completely revolutionary. Something that honored tradition while boldly rejecting its limitations.

As the song reached its climax, John’s voice hit notes that seemed to contain all the hope and frustration of a generation born during wartime. Raised on rationing and coming of age in an era of unprecedented possibility. The harmonies around him swelled and intertwined, creating something that was unmistakably the sound of four individuals becoming something greater than their individual parts.

When the song ended, the silence was profound. Four young men stood in BBC Studio B, breathing slightly hard, waiting to learn whether they had just launched their careers or confirmed their irrelevance. In the control room, Sir Reginald Peton sat motionless. His assumptions about provincial music and workingclass talent lying in ruins around him.

Then, unexpectedly, applause began. Not from the control room, but from somewhere else in the building. A young BBC secretary named Margaret Walsh had been filing papers in an adjacent office when the music began. She had stopped working, drawn by sounds unlike anything she had heard on British radio. Margaret was 22, the daughter of a Birmingham factory worker who had saved for months to pay for the secretarial course that got her this BBC position.

She had taken the job because it was respectable, steady, safe. But she had always harbored secret dreams of making music herself. Dreams she had learned to keep quiet in an environment where ambition was expected to stay within proper boundaries. Now she stood in the corridor clapping with genuine enthusiasm for music that spoke to something she had not known she was missing.

Tears ran down her cheeks as she realized that this was what music could be when it came from someplace real, someplace honest, some place that didn’t apologize for its origins or ask permission to exist. Other BBC employees began gathering. Engineers emerged from their studios, still wearing headphones around their necks.

Producers left their offices, abandoning important meetings to investigate the commotion. A cleaning woman named Mrs. Davies, who had been emptying waste baskets, stood transfixed in the hallway, her cart forgotten, a young technician named Peter, barely 18 and working his first job out of technical college, pressed his face to the studio window, watching the Beatles with the expression of someone witnessing the future arrive ahead of schedule.

Within minutes, a crowd had formed outside Studio B, drawn by music that seemed to announce the arrival of something entirely new in British popular culture. Conversations buzzed in the corridor as employees tried to process what they were hearing. “Who are they?” someone whispered. “Where did they come from?” asked another voice. A senior producer who had worked at BBC for 20 years stood shaking his head in amazement.

“I’ve never heard anything like that,” he said to no one in particular. “Never.” Sir Reginald Peton looked around his control room, seeing his colleagues faces reflecting his own amazement. He pressed the intercom button. Gentlemen,” his voice carried into the studio. But now there was respect where there had been dismissal.

That was quite extraordinary. Might we hear another? John looked at his bandmates. Paul nodded. George smiled for the first time since arriving in London. Ringo counted them in. “Please, please me followed, and with it the complete transformation of everything Sir Reginald Peton thought he knew about popular music.

The song was faster, more complex, more emotionally direct than anything currently played on BBC radio. It was music that demanded attention that refused to function as mere background entertainment. But beyond the musical innovation, something else was happening in that studio. The Beatles were not performing for the BBC executives.

They were sharing something deeply personal, something that grew out of their shared experiences, their friendship, their absolute belief in the power of music to transcend the limitations others placed on working-class ambition. When the second song ended, the crowd outside Studio B had grown larger. BBC employees, who had never shown interest in popular music, found themselves drawn to sounds that seemed to capture something essentially British yet completely contemporary.

Margaret Walsh pressed her face to the corridor window, watching four young men who were changing everything with nothing more than guitars, voices, and an unshakable faith in their own vision. Sir Reginald Peton stood up in the control room, his usual composure completely abandoned. He walked into the studio, approaching the four Beatles with an expression that mingled amazement with something approaching apology.

Gentlemen,” he said, his Oxford accent somehow seeming less important than it had 30 minutes earlier. “I owe you an apology. When you arrived today, I thought I was doing George Martin a favor by giving you 5 minutes. I now realize that you were doing me a favor by sharing those 5 minutes with us.” John’s response was typically direct.

We’re just four lads from Liverpool who love making music. Nothing more complicated than that. Perhaps, Peton replied, “But you’ve just reminded me why I fell in love with music in the first place.” Before committees and protocols and worries about what’s appropriate for afternoon audiences, the immediate aftermath was unlike anything in BBC history.

Phone calls began flooding the switchboard from listeners who had heard the impromptu session broadcast live. Record shops received inquiries about Beatles recordings. Radio producers from commercial stations called offering unprecedented contracts. But the most significant response came from Margaret Walsh, the young secretary who had stopped her filing to listen.

She approached the Beatles as they packed their instruments, her eyes bright with tears she couldn’t quite explain. “Thank you,” she said simply. “I’ve been working here for 2 years, listening to the same safe music every day. What you just played, it made me remember why I loved music before I started working in the music business.

” Paul smiled at her warmth. Music should make you feel something. If it doesn’t, what’s the point? I used to play piano, Margaret continued. Gave it up when I started working. Thought it wasn’t practical. But listening to you, I think I might start again. You should, George said quietly.

Music doesn’t care about practical. It cares about honest. 6 months later, Margaret Walsh had left her BBC secretarial position to pursue music full-time. She never became famous, but she spent years teaching children in East London schools, sharing her belief that music belonged to everyone, not just those with proper accents and expensive educations.

She would tell her students about the day four young men from Liverpool changed everything with nothing more than courage and authenticity. Many of those students went on to form their own bands, carry on their own musical revolutions, create their own moments of transformation in small clubs and school assemblies across London.

The Beatles left BBC broadcasting house that afternoon with a commitment for regular appearances on Saturday club, but more importantly with the knowledge that authenticity was more powerful than artifice, that workingclass perspectives had value in middle class spaces, that music could break down barriers others insisted were permanent.

They walked out into the London evening feeling taller than when they had entered, carrying themselves with the confidence that comes from proving everyone wrong while staying true to everything right. Sir Reginald Peton continued as head of BBC light program, but his programming philosophy was forever changed. He began seeking out artists who brought genuine innovation rather than safe imitation.

He championed musicians from backgrounds similar to the Beatles, understanding finally that the most revolutionary art often came from the most unlikely sources. He would later credit that afternoon in Studio B as the moment he remembered why he had fallen in love with music in the first place before committees and protocols had made him forget that music’s purpose was to move hearts, not satisfy corporate strategies.

The ripple effects extended far beyond Broadcasting House. Other radio producers hearing about the BBC session began reconsidering their own assumptions about regional accents and workingclass authenticity. Record companies started sending scouts to Liverpool in Manchester in Birmingham looking for the next group of provincial boys who might contain similar magic.

Music venues across Britain began booking acts they would have dismissed months earlier. Understanding that the definition of professional quality had been forever expanded. Years later, when the Beatles had become the most famous musicians in the world, Peton would tell the story of that October afternoon in Studio B to anyone who would listen.

how four workingclass lads from Liverpool had taught him that class was less important than creativity, that regional accents were less significant than authentic voices, that the establishment’s role was not to protect tradition from change, but to recognize and nurture change that honored tradition’s best elements.

They didn’t just perform that day, he would say in interviews decades later. They taught us how to listen properly. The performance lasted 10 minutes. the lesson it taught would last forever. Real music doesn’t ask permission from those who consider themselves its guardians. It simply refuses to be ignored.

And in refusing it changes