Bigfoot Caught Digging Graves on Trail Cam, What Happened Next Is Shocking – Sasquatch Story

THE GRAVEYARD KNOCKS

A Spring Creek confession

Chapter 1 — The Camera on the Pine

Late spring of 2015, up in the Appalachian foothills, I was forty-three and living alone after a divorce that left my house echoing and my life feeling like it had been thinned out. When you lose a marriage, people talk about freedom like it’s a prize, but what it feels like at first is an empty room where sound doesn’t bounce right. So I went back to the mountains more often, back to the places my grandfather taught me to read like a book—deer trails that cut the ridges, old logging roads that hadn’t seen a truck in thirty years, and the family cemetery tucked into a small clearing above Spring Creek like a private paragraph written into the land.

.

.

.

My father taught me you don’t let family ground go wild. You check it every few weeks. You clear weeds twice a year. You replace markers when they rot. You keep the names readable because forgetting is the one kind of death you can prevent. The cemetery held eight graves, family going back to the 1890s, when my great-great-grandfather homesteaded the land and decided the mountain would be home even if home was hard. My grandfather was up there too—stubborn, decent, buried under the same hemlocks he used to cuss at when they dropped branches on his truck.

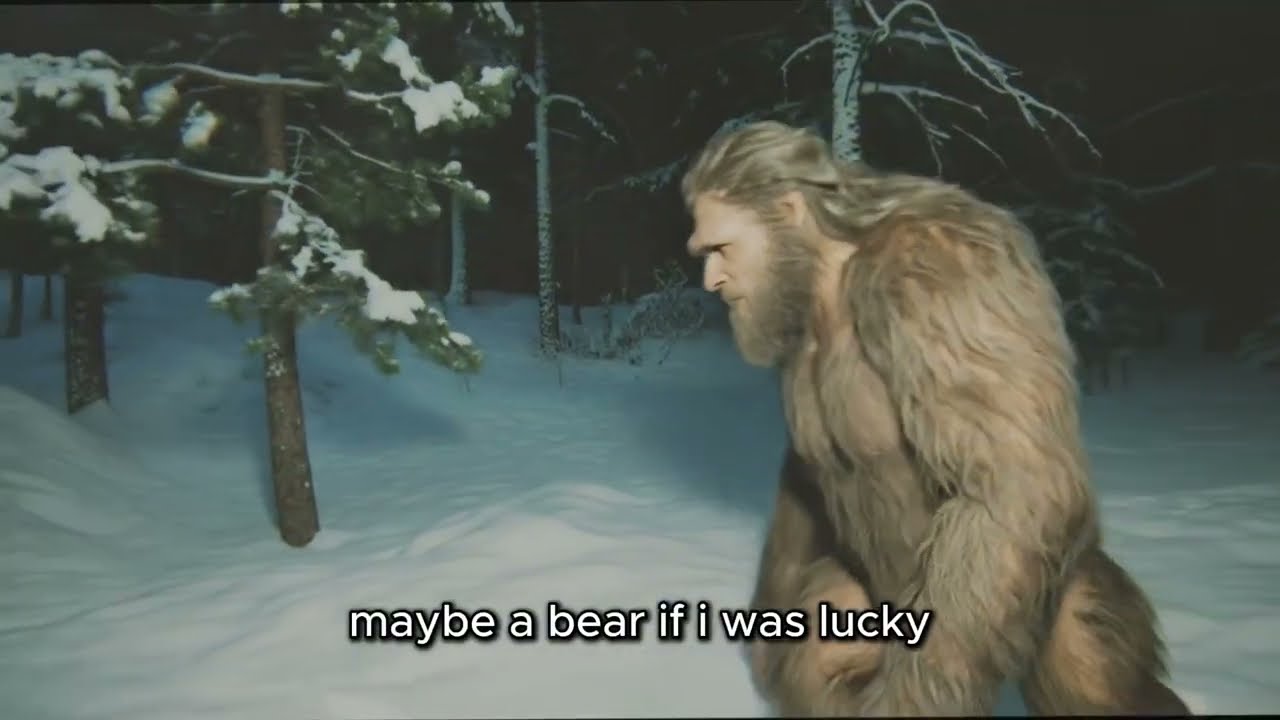

The trail cam I set up wasn’t anything special, a cheap sixty-dollar unit from the hardware store, meant for deer and maybe a black bear if you were lucky. I strapped it to a pine fifteen yards from the graves and angled it so it would catch anything moving through the clearing at night. I told myself it was out of habit—same way you lock your door even when you haven’t had trouble in years. But the truth is I’d been feeling watched in my own life for a while, watched by regret, watched by loneliness, and maybe I thought the camera could watch the world back on my behalf.

That evening I sat on my porch with a beer, listening to the forest settle. Crickets started around eight, an owl called deeper in the holler, and the air cooled just enough to make you forget the day’s humidity. I remember thinking it was a perfect night—the kind where nothing feels wrong. I didn’t hear anything unusual. No knocks. No strange calls. Just the normal symphony of late spring. Three days later, the mountain taught me the difference between “normal” and “familiar.”

Chapter 2 — Thump, Thump, Thump

I was at my kitchen table with coffee and an old Field & Stream when I heard the knocks. Three of them—solid, deep, deliberate—like a bat hitting a hollow tree. They came from the direction of the cemetery, not close enough to rattle windows, but close enough to carry through the woods in a way that made my scalp tighten. Thump… thump… thump. Even spacing, maybe two seconds apart. Then nothing.

For a few minutes I tried to talk myself down. Branch falling, woodpecker, some quirk of sound bouncing off the ridge. But woodpeckers don’t knock three times and stop. Branches don’t fall with rhythm. Rhythm is intention. I sipped my coffee anyway, because sometimes pretending is the only thing that keeps you from bolting for a gun you don’t actually want to use.

The next morning I drove up the old logging road as far as my truck would go, then hiked the rest. Birds sang. Squirrels made their usual racket in the canopy. By the time I reached the clearing, the cemetery looked exactly as it always did—markers upright, weeds creeping, no obvious disturbance. The trail cam’s indicator light said it had been recording. I pulled the SD card and headed back with a calm I didn’t trust.

That afternoon I plugged the card into my laptop. The camera had captured the usual parade: deer at dusk, raccoon nosing around a marker, fox crossing before dawn. Normal. I was about to close the program when I noticed a timestamp: 2:47 a.m. The clip opened in grainy infrared, the clearing washed in pale light like an old nightmare.

At first I thought the motion sensor had triggered on shadows. Then I saw it. Something large was kneeling at my grandfather’s grave. It was digging—slowly, deliberately—using hands, not paws, moving earth with the care of someone doing work they’d done many times before. The figure’s shoulders were broad, covered in dark hair that showed gray in the infrared. Even on its knees it looked seven feet tall. It worked for almost three minutes, then stood.

That’s when my stomach truly dropped. Standing, it was eight feet—maybe more. It turned its head, not directly at the camera, but scanning the clearing, and for a second the profile caught the IR glow: heavy brow, flat nose, face wrong for a human and wrong for any bear. Then it walked into the trees and disappeared as if it had never been there at all.

I replayed the clip five times, each time praying my eyes would find an explanation. A man in a costume. A trick of angles. Anything but what my mind kept circling: I’d filmed something people argue about like a campfire story. I’d filmed Bigfoot kneeling at my grandfather’s grave like it belonged there.

Chapter 3 — The Perfectly Refilled Earth

I didn’t sleep that night. Every time I shut my eyes I saw those hands moving dirt, careful as a person planting flowers. At dawn I hiked back to the cemetery because I needed daylight to tell me the truth. The morning was almost offensively peaceful—sun slanting through pines, birds singing like nothing in the world had changed.

The grave looked undisturbed. The ground was level. If something had dug there, it had filled the hole back in so perfectly I couldn’t find the seam. I knelt, ran my fingers over the soil, feeling for looseness. Nothing. That bothered me more than if I’d found a mess. Mess I understood. Precision was something else.

Then I found a single footprint at the edge of the clearing, half hidden by tall grass in a patch of soft mud. It was enormous—seventeen inches long, five toes clear, pressed two inches deep. No claw marks. No boot tread. Just a clean, heavy impression like the earth had been stamped by something that didn’t worry about leaving evidence.

I took photos. Then I stood there with my phone in my hand and thought about calling the sheriff. Twenty minutes down the mountain was a non-emergency number and a deputy who’d probably come up, glance at my pictures, and decide I was either drunk or bored. I could already hear the laughter, the way it would spread. Or worse, the way belief would spread. If I showed anyone that footage, I wouldn’t be sharing a secret; I’d be lighting a signal flare.

As I left the cemetery, a smell rolled through the treeline—thick, musky, like wet fur and turned earth. Not bear. I’d hunted bears with my father. This was heavier, older, clinging to the air like fog. The feeling of being watched pressed against my back so hard it felt physical. I walked faster than I wanted to admit, glancing over my shoulder like a man who knows he’s not alone but doesn’t want to see what’s behind him.

Back at my cabin, I locked the door, drew the curtains, and watched the footage one more time in the dark kitchen. The creature didn’t move like a predator. It moved like a visitor. And that word—visitor—made my skin prickle because visitors have reasons. Visitors choose where they go.

Chapter 4 — Scratches on the Siding

Four nights later, the knocks returned. I was on the porch at dusk, beer in hand, trying to convince myself I could forget the footage and get back to a life where the scariest thing was an empty bed. Then: thump, thump, thump. Loud and clear from the woods. Closer than before—maybe half a mile off instead of two miles. The sound landed in my chest like a warning I couldn’t translate.

I went inside, locked up, and sat in the dark living room listening. The knocks didn’t repeat, but my nerves didn’t unclench. The next morning I drove to the cemetery again. The footprint was gone, washed by rain, but the air carried that faint musky edge and near the treeline I found a stack of stones on a fallen log—five stones, carefully balanced, placed with intention.

That week the knocks continued, every few nights, always three, always after dark. I started writing down times like I was building a case file: 9:47 p.m., 10:50 p.m., 11:03 p.m. Never exact, never predictable, but consistent enough to feel like a pattern. I drank more. Slept less. Lied to my brother in Asheville when he called, telling him the mountain quiet was doing me good.

Then I found scratches on the back wall of my cabin—four parallel gouges carved into the siding eight feet off the ground. Deep marks, seven inches long, as if something had dragged a hand across the wood just to remind me it could. I stood there staring at the scratches while the word I didn’t want kept circling my head like a hawk: Bigfoot. Real. Close enough to touch my house.

I read everything I could online, sifting through hoaxes and nonsense until I found accounts that felt like mine—people who weren’t trying to sell a book, people who sounded like they’d swallowed their own disbelief. One story hit hard: a hunter in Northern California reporting graves disturbed in an old pioneer cemetery, cameras catching a huge figure kneeling by markers at night. The comments were cruel. The thread was a graveyard of ridicule. The man said he destroyed the footage because it ruined his life.

That was when I promised myself I wouldn’t share mine. Not because I didn’t want the world to know, but because I didn’t want the world to come.

Chapter 5 — The Basket of Flowers

June bled into July and the knocks became something I hated for how familiar they were. Not constant, but steady—enough to keep my nerves tuned to the woods. I checked the cemetery every other day. Sometimes there were signs: stone stacks, arranged branches, the musky smell thick near the treeline. Other times there was nothing but graves and weeds, as if the forest had never been touched.

I started noticing something in the footage that I hadn’t wanted to admit: the creature wasn’t vandalizing. It wasn’t tearing markers apart or digging like a scavenger. It was careful. Reverent, even. It touched the dirt the way my father touched a headstone—like the ground beneath it deserved respect. That realization shifted my fear into a different shape. Maybe I wasn’t looking at a threat. Maybe I was looking at a ritual.

Then late in July, after a storm, I hiked up and found a woven basket placed on my grandfather’s marker. Not modern. Not store-bought. It was made from thin branches and vines, tightly woven, symmetrical in a way that took attention and skill. Inside were fresh wildflowers—black-eyed Susans and mountain laurel—arranged with care like an offering.

I approached as if I was walking into church. The basket felt heavy in my hands, sturdy and real. And the smell hit—strong, close, the musky odor of wet fur and earth. I spun toward the treeline, scanning shadows, and though I saw nothing, I knew I was not alone.

“Thank you,” I said aloud, because my mouth needed to do something besides lie. “Thank you for the flowers.”

The forest answered with silence, but the silence felt different—less empty, more attentive. I carried the basket home, stared at it on my kitchen table for an hour, then returned it to the grave where it belonged. If this was a ritual, it wasn’t mine to steal. That night, when the knocks came at 11:47, they sounded less like warning and more like acknowledgment, as if something had heard me and approved of my choice.

Chapter 6 — Dale Patterson Hears Them Too

In early September my neighbor Dale Patterson stopped by. He ran a small sawmill, logged these mountains for thirty years, and had the kind of quiet competence that made you trust his judgment even when you didn’t want to. He didn’t waste time with pleasantries. “Still hearing those knocks?” he asked, and my chest tightened.

He and his wife couldn’t sleep, he said. They called the sheriff. A deputy drove around for an hour, found nothing, blamed hunters or kids. Dale looked at me hard. “But I know you know something. You’re up there all the time.”

I lied because truth felt like a match held over gasoline. Sound carries strange in these hollows, I told him. Logging echoes. Trees fall. Dale didn’t believe me, but he let it go. After he left, I sat on my porch until dark, listening, and when the knocks came at 10:23, I thought about how many ears might be hearing them, how secrets in small mountain communities don’t stay buried unless you shovel dirt onto them yourself.

Around that time a man came to my door—Tom Brereslin, a wildlife researcher with the state. Clean-cut, clipboard, hiking clothes too new. He asked about unusual activity: vocalizations, big predator signs, three knocks in sequence. I gave him nothing but shrugs. After he left, I burned his card in my fireplace like it was cursed.

When I found a state camera mounted near the cemetery clearing, angled perfectly to catch anything approaching the graves, something in me snapped into a hard clarity. That night I hiked up with wire cutters and a hammer and destroyed it. Smashed the memory card, buried the pieces. If they asked, I’d blame vandals. Bears. Anything. It wouldn’t stop them forever, but it might buy time.

The knocks came afterward, softer, cautious, like whatever lived in those woods knew the danger had increased.

Chapter 7 — The Promise and the Return

October brought early dustings of snow on the high ridges. The knocks stopped for two weeks. Every time I checked the cemetery it was quiet—no baskets, no stones, no smell. Brereslin came back twice, more frustrated each time, eyes lingering on me like he could smell my lies. Then Dale called, voice tight. “You need to come down here. Bring a gun.”

Something had torn through his fence line, snapped posts like toothpicks, left huge tracks in the mud—seventeen inches, five toes, deep impressions. Dale stared at the damage and said what I’d been refusing to say out loud: “That ain’t no bear.” He looked at me and I knew the lie wasn’t going to hold.

So I told him—about the footage, the knocks, the basket of flowers, the face-to-face moment at the cemetery when I finally saw it at the treeline, massive and still, eyes dark and intelligent. I made him promise: no cops, no reporters, no internet. Just us. Dale agreed, pale as he listened, then helped me cover tracks and fix fences like we were cleaning up after a storm.

That night the knocks came from the direction of Dale’s place—three solid thumps, clear and strong. Not angry. Almost… approving. Like the creature knew two humans were protecting its secret now, not just one.

Years later I sold the cabin. Dale is gone now. But the mountain remains, and the cemetery remains. Last week—five years after I’d moved away—I drove up the old road and walked to the clearing. The graves were maintained. The markers straight. And on my grandfather’s stone sat a woven basket of fresh wildflowers, arranged carefully, reverently, as if someone had never stopped visiting.

As I turned to leave, I heard it—three faint knocks from deep in the trees. Thump, thump, thump. Not close enough to threaten. Close enough to confirm. I smiled and kept walking because some mysteries don’t want to be solved, only respected. And some secrets, once you’ve carried them for long enough, become part of the land itself.