April 15th, 1944, 25,000 ft above Germany, Lieutenant Colonel Dutch Ryan’s P-51 Mustang screamed through the thin air, chasing a Messor Schmidt 109 that danced just beyond his gunsite. For 3 years, American pilots had dominated European skies through sheer determination in superior numbers.

Their 30% hit rate in air-to-air combat was considered exceptional by military standards. Ryan squeezed the trigger, watching his tracers arc harmlessly behind the German fighter as it banked hard left. The Luftwaffa pilot knew the game, stay mobile, forced the Americans to guess their lead, exploit the split-second hesitation that came with deflection shooting.

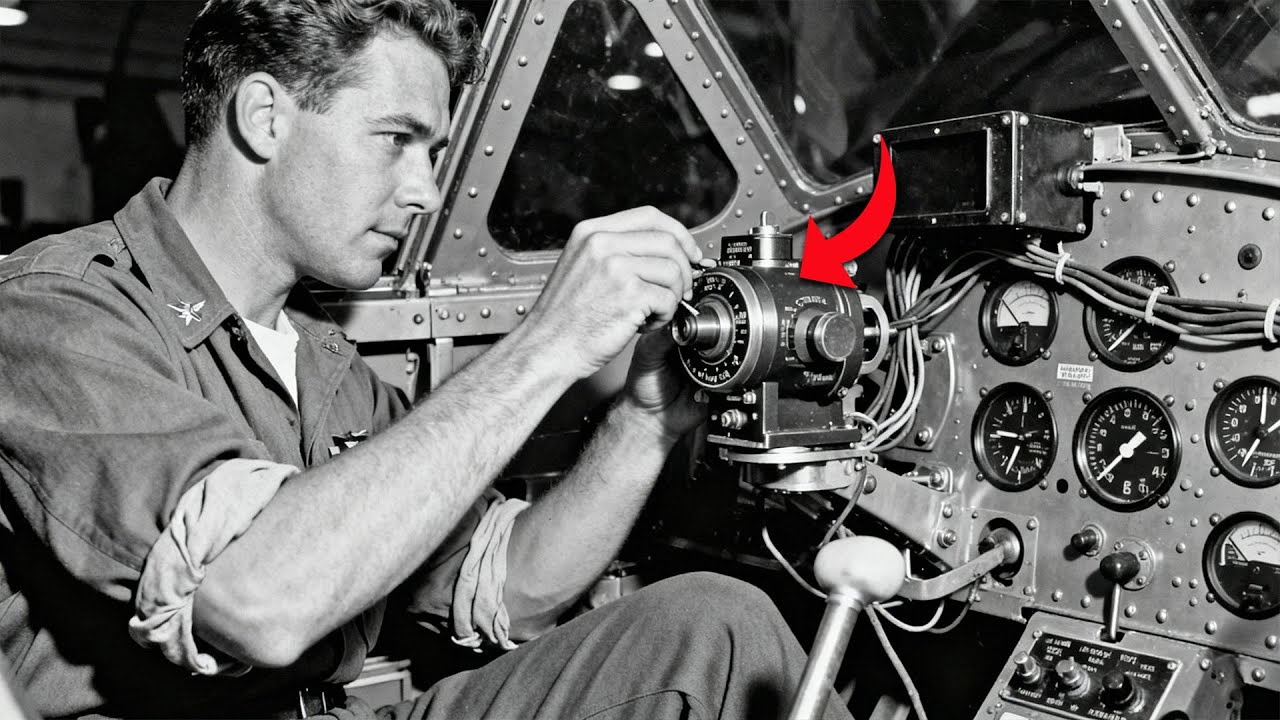

Traditional gunnery demanded intuition, experience, and luck. But 8 miles below, in a Sperry gyroscope laboratory, Major George Miller was installing something the Germans had never encountered. A mechanical brain that could calculate deflection angles faster than any human pilot, a gyroscopic site that tracked targets automatically, computing lead times for aircraft moving at 450 mph.

The K14 gun site promised to turn gunnery from guesswork into precision science. Ryan would soon discover that hitting what you cannot see was no longer impossible. The morning briefing, at least in airfield, carried the same weight it had for months. Another escort mission deep into German territory. Another day of watching flying fortresses lumber toward their targets while Messids and Faula Wolves tried to tear them apart.

Lieutenant Colonel Dutch Ryan stood before his pilots in the drafty briefing hut, pointing to reconnaissance photos that showed the rail yards at Schweinfort. The ballbearing factories there had been rebuilt twice already. Today, they would try to flatten them a third time. Ryan’s finger traced the route on the map.

We’ll pick up the bombers over the channel at 0800. Expect company the moment we cross into German airspace. He paused, studying the faces of his squadron commanders. These men had flown dozens of missions together, had watched friends spiral down in flames over the Reich’s industrial heartland. They knew the mathematics of aerial combat better than any textbook could teach.

In a high-speed engagement, hitting a maneuvering target required leading your shots by precise angles that changed every fraction of a second. missed by two degrees and your bullets passed harmlessly behind the enemy’s tail. Lead by too much and you fired into empty sky. The statistics painted a sobering picture.

American fighter pilots achieved hits on enemy aircraft roughly 30% of the time in combat conditions. This figure, while respectable by military standards, meant that seven out of every 10 firing passes resulted in wasted ammunition and missed opportunities. More critically, those missed shots often came at moments when American bombers were under attack.

When every second counted, when the difference between hitting and missing could mean the difference between a crew making it home or vanishing into the German countryside. Captain Dick Coker raised his hand from the back of the room. Sir, what about those new sites they’ve been testing? Any word on when we might see them? The question hung in the air like smoke.

Everyone had heard rumors about experimental gun sites, computing devices that supposedly eliminated human error in deflection shooting. Most dismissed such talk as engineering fantasy, the kind of impossible gadget that looked impressive on paper, but would never survive the violence of aerial combat.

Ryan had seen the preliminary reports from Wrightfield. The K14 gyroscopic gun site developed by Sperry gyroscope company with input from British Fanti engineers represented a radical departure from traditional gunnery methods. Instead of relying on pilot intuition to calculate lead angles, the site used mechanical gyroscopes to track a target’s movement and automatically compute the proper deflection.

The device could theoretically compensate for target speeds up to 450 mph at ranges extending from 600 to 2,000 yd. performance parameters that exceeded anything previously attempted in aerial gunnery systems. But Ryan also knew the resistance such innovations faced within the Army Air Force’s hierarchy. Colonel Bill Felin, chief of fighter operations for the European theater, had made his position clear during a heated discussion at 8th Air Force headquarters the previous month.

Pilots win battles, not gadgets, he had declared, dismissing the K-14 as an unnecessary complication that would distract air crews from proven combat techniques. Felin represented a significant faction within the military establishment that viewed technological solutions with deep suspicion, preferring to rely on human skill and conventional tactics.

The tension between innovation and tradition had been brewing for months. While engineers at Sperry worked 18-hour days refining the gun sight’s gyroscopic stabilization system, military officials debated whether American pilots even needed such assistance. After all, the Luftvafa was already showing signs of strain.

Fuel shortages limited German training programs, and experienced pilots were being shot down faster than they could be replaced. Why risk introducing untested equipment when current methods seemed adequate? Ryan understood both perspectives. He had witnessed the frustration of skilled pilots missing clean shots at enemy aircraft, had seen bombers fall victim to fighters that might have been destroyed if American gunnery had been more precise.

But he also recognized that changing established procedures in the middle of a war carried significant risks. Pilots trained for months to master deflection shooting using traditional ring and bead sights. Introducing a complex gyroscopic system would require extensive retraining, potentially degrading squadron readiness during the critical months leading up to the anticipated invasion of France.

The morning mission proceeded exactly as Ryan had predicted. The 357th fighter group intercepted the bomber stream over Dover, their P-51 Mustangs sliding into escort formation as the flying fortresses turned southeast toward the continent. German radar detected the formation before it crossed the French coast.

And within minutes, yellow-nosed messers were climbing from airfields scattered across occupied Europe. The engagement that followed illustrated perfectly the challenges American pilots faced in aerial gunnery. Ryan watched Captain Coker pursue a lone Messor Schmidt 109 through a series of tight turns. The German pilot executing textbook evasive maneuvers designed to frustrate American firing solutions.

Coker fired three separate bursts, each time leading his target by what appeared to be the correct deflection angle. The first burst passed behind the Messor Schmidt’s tail section. The second group of bullets arked wide to the right as the German pilot rolled inverted. The third burst might have scored hits, but the enemy fighter had already disappeared into a cloud bank, leaving only the acrid smell of cordite and the bitter taste of another missed opportunity.

Similar scenarios played out across the sky that morning. American pilots flying superior aircraft with adequate ammunition supplies found themselves unable to convert tactical advantages into decisive results. The 30% hit rate that characterized American aerial gunnery reflected not a lack of courage or skill, but rather the inherent limitations of human perception and reflexes when attempting to solve complex ballistic problems in three-dimensional space at closing speeds that often exceeded 700 mph.

Meanwhile, 8,000 miles away in a Long Island laboratory, Major George Miller was conducting the final calibration tests on a device that promised to transform these frustrating engagements into precise, predictable encounters. The K14 gun site incorporated gyroscopic sensors that could track a target’s angular velocity in real time, feeding this information to a mechanical computer that calculated the exact point in space where bullets and target would intersect.

The system eliminated guesswork, removed human error from the gunnery equation, and theoretically allowed pilots to engage enemy aircraft under conditions that had previously made accurate shooting impossible. But Miller faced his own battles in the laboratories and conference rooms of wartime America. Convincing skeptical military officials to embrace radical technological change required more than successful test results.

It demanded overcoming institutional inertia, bureaucratic resistance, and the deeply held belief that American pilots could win the war using traditional methods and superiors. Courage. The fluorescent lights in building 7 at Sperry Gyroscope Company cast harsh shadows across the workbench where Major George Miller hunched over a maze of precision components.

Gyroscopes no larger than a man’s fist sat beside delicate servo motors and tiny gear trains. Each piece representing months of development work. Miller’s hands moved with practiced precision as he adjusted the sensitivity settings on the latest K14 prototype. His engineer’s mind focused on solving a problem that had frustrated aerial gunners since the first fighter pilots took to the skies.

The challenge appeared deceptively simple. When an enemy aircraft maneuvered during combat, a pilot had to predict where that target would be when his bullets arrived, not where it was when he pulled the trigger. At typical engagement speeds, this prediction required calculating deflection angles that change continuously as both aircraft maneuvered through three-dimensional space.

Human pilots, even the most experienced, relied on intuition and split-second visual estimates to solve these ballistic puzzles. The 30% hit rate achieved by American fighter pilots reflected the inherent limitations of this approach. Miller’s solution bypassed human perception entirely. The K14 used a gyroscopically stabilized optical system that tracked a target’s angular movement in real time.

As the pilot kept his target centered in the sight’s reticle, mechanical computers built into the device calculated the target’s rate of angular movement. combined this data with range estimates and known ballistic characteristics of the aircraft’s guns, then projected the proper aiming point directly onto the pilot’s field of view.

The system eliminated guesswork, transforming gunnery from an art into a precise science. But translating this concept into functional hardware presented formidable engineering challenges. The gyroscopes required to stabilize the site had to operate flawlessly under the extreme conditions of aerial combat, subjected to gravitational forces exceeding six times normal Earth gravity, temperature variations from -40° F at high altitude to over 100° in desert climates and constant vibration from aircraft engines and machine gun recoil. Traditional

gyroscopes used in naval applications or groundbased systems simply could not survive such punishment. Miller had spent the previous eight months redesigning every component of the system. The gyroscope housings were machined from aircraft grade aluminum. Their internal mechanisms precision balance to tolerances measured in thousandth of an inch.

The servo motors that adjusted the sight’s aiming reticle incorporated shockabsorbing mounts to isolate them from aircraft vibration. Even the electrical connections used specialized combat rated cables that could withstand the physical stresses of high-speed maneuvering. The breakthrough had come during a test conducted in February.

Miller’s team had mounted a prototype K14 in a specially modified P-51 Mustang and subjected it to a punishing series of aerobatic maneuvers designed to simulate combat conditions. Previous prototypes had failed spectacularly under such treatment. Gyroscopes tumbling out of alignment, servo motors seizing due to excessive gravitational loads, optical elements shattering from vibration stress.

But the February test unit had emerged from 20 minutes of violent maneuvering with its calibration intact and all systems functioning normally. The implications were staggering. Ground tests using film footage of maneuvering targets showed that pilots using the K14 could achieve hit rates exceeding 70% under conditions where traditional sights yielded success rates below 20%.

The device proved especially effective at long range where human pilots struggled most with deflection calculations. Targets at distances of 1500 to 2,000 yards, previously considered almost impossible to hit while maneuvering, became viable shooting opportunities with the gyroscopic site. However, Miller faced resistance that had nothing to do with technical limitations.

Colonel Felin’s opposition to the K14 reflected broader institutional skepticism within the Army Air Forces regarding technological solutions to combat problems. Many senior officers had risen through the ranks during an era when pilot skill and aircraft performance determined the outcome of aerial engagements. The notion that mechanical devices could enhance or even replace human judgment struck them as fundamentally misguided.

This resistance manifested in bureaucratic obstacles that threatened to delay the K14’s deployment indefinitely. Procurement officials questioned whether the site’s complexity would compromise aircraft reliability. Training officers worried that pilots would become overly dependent on the device, losing the fundamental gunnery skills that had served them well in earlier conflicts.

Supply personnel calculated the logistical burden of maintaining thousands of precision instruments in forward combat areas where spare parts and skilled technicians remained perpetually scarce. Miller understood these concerns, but believed they missed the larger strategic picture. American industrial capacity was producing fighter aircraft at unprecedented rates.

But the effectiveness of these machines depended entirely on their pilots ability to hit enemy targets. Every missed shot represented wasted ammunition, lost opportunity, and potentially American bomber crews who would not return home. The K14 offered a solution that could multiply the effectiveness of existing aircraft without requiring new production lines or extensive modifications to proven designs.

The devices development had also benefited from British research conducted at Ferranti Limited. British engineers working under different operational constraints in the European theater had pioneered many of the fundamental concepts underlying gyroscopic gun sites. Their Mark 2 gyro site used in Royal Air Force Spitfires and Hurricanes had demonstrated the viability of mechanically computed gunnery solutions.

However, the British device remained relatively primitive compared to Miller’s design, lacking the range capability and target tracking precision that American tactical requirements demanded. Miller incorporated lessons learned from British combat experience while addressing uniquely American operational needs.

The K-14 was designed to function effectively at the extended ranges typical of American escort fighter missions where P-51 Mustangs often engaged enemy aircraft at distances exceeding 1,000 yd. The site’s gyroscopic stabilization system compensated for the high alitude turbulence frequently encountered during bomber escort operations.

Most importantly, the device was engineered for mass production using American manufacturing techniques and readily available materials. Production planning presented its own complexities. Sperry’s manufacturing facilities were already operating at maximum capacity, producing gyroscopic equipment for naval vessels, aircraft navigation systems, and anti-aircraft gun directors.

Establishing dedicated production lines for the K14 would require diverting resources from other critical military programs. Miller estimated that achieving meaningful production volumes would take at least 6 months from the date of final military approval, time that American pilots could not afford to lose.

As the war approached its climactic phases, the urgency became more apparent with each combat report from European airfields. German pilots, despite fuel shortages and reduced training time, continued to inflict significant casualties on American bomber formations. Luftvafa fighters armed with heavy cannon could destroy a flying fortress with a few well-placed shots, making every miss by American escort pilots a potentially fatal error.

The mathematics were brutal and unforgiving. American bomber losses averaged approximately 4% per mission over German territory, rates that could not be sustained indefinitely without compromising the strategic bombing campaign that military planners considered essential for victory in Europe.

Miller knew that his gyroscopic site represented more than an incremental improvement in existing technology. It embodied a fundamental shift in how aerial warfare would be conducted, transforming individual pilot skill into a systematically enhanced capability that could be reproduced across entire fighter squadrons. The question was whether institutional resistance and bureaucratic inertia would prevent this transformation from occurring while it could still influence the war’s outcome.

The telegram arrived at Lyston airfield on a gray morning in late April, its contents disrupting the routine that had governed the 357th fighter group for months. Lieutenant Colonel Dutch Ryan read the message twice before calling his squadron commanders into the briefing room. The Army Air Force’s technical command was requesting volunteer pilots for experimental equipment testing, specifically evaluation of an advanced gyroscopic gun site that promised to revolutionize aerial gunnery.

Ryan studied the faces around the table. These men had flown through the worst the Luftvafa could offer, had watched friends disappear into German flack fields, had nursed damaged aircraft home across hundreds of miles of hostile territory. They possessed the hard-earned skepticism of combat veterans who had seen too many promising innovations fail when subjected to the brutal realities of warfare.

Captain Dick Coker spoke first, voicing what everyone was thinking. Sir, with respect, we’ve heard about miracle weapons before. Most of them work better in laboratories than in combat. The response reflected deeper concerns about introducing untested equipment during a critical phase of the European campaign.

Allied planners were finalizing preparations for the cross channel invasion, an operation that would require absolute air superiority over the landing beaches. fighter squadrons could not afford to compromise their effectiveness by experimenting with unproven technology during such a crucial period. Every pilot, every aircraft, every mission counted toward the larger strategic objective of establishing a foothold in occupied Europe.

Yet Ryan recognized that the current situation was far from satisfactory. The previous week’s mission to Berlin had illustrated the persistent problems with American aerial gunnery. His pilots had encountered a formation of Foca Wolf 190 fighters attacking a group of B17 flying fortresses over Brandenburgg. Despite achieving favorable tactical positions and firing numerous bursts at the German aircraft, the Americans had managed to shoot down only two enemy fighters while losing three bombers to concentrated cannon fire. The engagement had lasted

less than 10 minutes, but it represented months of frustration compressed into a brief violent encounter. The technical specifications accompanying the telegram suggested that the K14 gyroscopic site might address these shortcomings. According to the test data, pilots using the device had achieved hit rates exceeding 60% during controlled trials compared to the 30% average recorded by squadrons using conventional ring and bead sites.

More significantly, the gyroscopic system remained effective at extended ranges where traditional gunnery methods became essentially useless. Ryan understood the broader implications. American fighter tactics had evolved around the limitations of existing gunsight technology. Pilots were trained to close to ranges of 400 yd or less before opening fire, accepting the increased vulnerability to enemy defensive fire in exchange for higher hit probabilities.

The K-14 promised to extend effective engagement ranges to over 1,000 yards, potentially allowing American fighters to destroy enemy aircraft while remaining outside the range of their defensive weapons. The decision to participate in the testing program required weighing immediate risks against potential long-term advantages.

Installing experimental equipment in combat aircraft violated numerous regulations designed to maintain standardization and reliability across operational units. If the gyroscopic sights failed during combat missions, pilots might find themselves unable to engage enemy targets effectively, compromising not only their own survival, but the safety of the bomber crews they were assigned to protect.

Miller’s team at Sperry had anticipated these concerns. The K14 incorporated backup systems that allowed pilots to revert to traditional gunnery methods if the gyroscopic components malfunctioned. The site’s optical elements functioned as conventional ring and bead systems when the gyroscopic stabilization was disengaged, ensuring that equipment failure would not leave pilots defenseless.

Additionally, the device was designed for rapid removal and replacement, allowing maintenance crews to swap faulty units without grounding aircraft for extended periods. The first K-14 installation took place on Ryan’s personal P-51 Mustang, a aircraft he had flown for over 40 missions without mechanical failure.

Sperry technicians worked through the night to mount the gyroscopic site, running calibration tests that continued until dawn. The device appeared deceptively simple from the pilot’s perspective, a standard gun site with additional controls for range estimation and target tracking sensitivity. But Miller’s engineers had packed extraordinary complexity into the compact housing, incorporating precision gyroscopes, mechanical computers, and optical systems that represented the cutting edge of 1944 technology.

The first test flight revealed both the sight’s potential and its limitations. Ryan engaged in mock combat with another Mustang flown by Captain Coker, attempting to achieve firing solutions while both aircraft maneuvered aggressively. The K14 performed exactly as advertised when Ryan could maintain the target within the sight’s tracking range, automatically calculating deflection angles and presenting accurate aiming points.

However, the device struggled during high-speed rolling maneuvers that caused the target to move unpredictably across the pilot’s field of view. These initial limitations prompted modifications to American fighter tactics. Rather than engaging in the turning fights that characterize previous air-to-air encounters, pilots using the K-14 learn to exploit their aircraft’s speed advantages to maintain favorable geometry for the gyroscopic sight’s operation.

The Mustang’s performance characteristics made it ideal for this approach, allowing pilots to dictate engagement conditions and maintain the stable tracking required for the site to function effectively. Subsequent test flights produced increasingly impressive results. Ryan discovered that the K-14 excelled in precisely those situations where conventional gunnery proved most challenging.

Longrange shots at targets flying straight and level previously considered waste of ammunition became high probability engagements. Deflection shots against targets executing general turns, virtually impossible with traditional sights, yielded consistent hits when the gyroscopic system was properly employed. The psychological impact proved as significant as the technical advantages.

Pilots using the K14 reported increased confidence during combat engagements, knowing that their equipment was calculating solutions to gunnery problems that had previously relied on intuition and luck. This confidence translated into more aggressive tactics and willingness to engage enemy aircraft under conditions that might have deterred pilots using conventional sites.

However, institutional resistance within the army air forces remained formidable. Colonel Felin’s opposition had gained support from other senior officers who questioned whether the benefits justified the costs and complications of widespread deployment. Production estimates suggested that equipping all American fighter squadrons with K-14 sites would require 6 months and divert manufacturing capacity from other critical programs.

Training requirements alone would remove experienced pilots from combat operations for weeks during a period when every available aircraft was needed for the upcoming invasion. Miller understood that technical success in controlled testing would not automatically translate into military adoption. The K-14’s fate depended on demonstrating conclusive advantages under actual combat conditions, proving that the device could enhance American fighter effectiveness while maintaining the reliability and simplicity that combat operations demanded. The window

for such demonstration was rapidly closing as Allied planners finalized their invasion timeline and military procurement officials faced mounting pressure to avoid any changes that might compromise operational readiness. The stakes extended far beyond the success or failure of a single weapon system. The K-14 represented a broader transformation in military technology.

A shift toward sophisticated electronic and mechanical systems that would define post-war warfare. Whether American forces embraced or rejected this transformation would influence not only the immediate outcome of the European campaign, but the future development of military aviation technology. The cost became personal on May 7th when Lieutenant Jimmy Watonabi failed to return from a mission over Munich.

Miller received the combat report that evening while reviewing production schedules in his Long Island office, the typewritten pages describing how Watonabi’s Mustang had been jumped by two Messers Schmidt 109’s while escorting bombers to the BMW aircraft engine factory. The 22-year-old pilot from California had gotten clean shots at both German fighters, but missed with every burst, his bullets passing harmlessly through empty sky as the enemy aircraft maneuvered out of his line of fire.

The Messorm had then turned on Watonab, their cannon shells tearing through his aircraft’s wings and engine cowling before sending him spinning toward the German countryside. Miller stared at the report until the words blurred together. Watanabi had been one of the most promising pilots in the 357th Fighter Group.

A natural marksman who had excelled in training but struggled with the deflection shooting that characterized aerial combat. His death represented more than a statistical casualty. It embodied the human cost of America’s inability to translate technological capability into battlefield effectiveness. The K14 gyroscopic site sat in Spar’s production facility, proven effective in testing, but stalled by bureaucratic inertia, while pilots died attempting to solve gunnery problems that the device could eliminate entirely. The emotional weight

of such losses had begun affecting Miller’s entire engineering team. These men worked 16-hour days perfecting mechanical systems that promised to save lives. Yet their efforts remained trapped in procurement channels and testing protocols while combat reports detailed the same frustrating scenarios week after week.

Young American pilots, many barely out of flight training, faced experienced Luftvafa veterans equipped with superior tactics and weapon systems. The technological advantage that the K-14 represented could tip the balance, but only if it reached operational squadrons before more pilots like Watnab paid the ultimate price for inadequate equipment.

Miller’s frustration deepened when he received Colonel Felin’s latest assessment of the gyroscopic sight program. The document circulated among senior Army Air Force’s officials characterized the K14 as an unnecessary complication that would distract pilots from fundamental gunnery skills. Felin argued that American fighter pilots were already achieving acceptable combat results using conventional methods and that introducing complex mechanical systems would create maintenance burdens that forward deployed squadrons could

not support effectively. The colonel’s opposition reflected broader institutional resistance within military aviation circles. Many senior officers had earned their reputations during an era when individual pilot skill determined combat outcomes, and they viewed technological solutions with suspicion bordering on hostility.

These leaders believed that courage, training, and superior aircraft design provided adequate advantages over enemy forces, making sophisticated fire control systems unnecessary complications that might actually degrade combat effectiveness. But Miller possessed information that contradicted these assumptions.

His connections within the technical intelligence community provided access to captured German aircraft and weapon systems that revealed the true scope of Luftvafa technological development. German engineers were developing air-to-air rockets, improved cannon systems, and advanced fighter designs that threatened to neutralize American numerical advantages through superior firepower and performance.

The war that Felin remembered, where individual skill and aircraft quality determined outcomes, was rapidly evolving into a technological arms race that would favor whichever side could field the most advanced systems most quickly. The urgency of this competition became apparent when Miller examined combat footage from recent engagements over Germany.

German pilots were employing new tactics specifically designed to exploit the limitations of American gunnery systems. Instead of engaging in traditional dog fights where superior American training might prevail, Luftwafa fighters were conducting high-speed hit-and-run attacks that minimized their exposure while maximizing the difficulty of American deflection shooting.

These tactics proved devastatingly effective against pilots using conventional ring and bead sights, but would be largely negated by the automatic tracking capabilities of the K-14 system. Miller decided to circumvent official procurement channels by arranging direct demonstrations for operational commanders who possess the authority to authorize field testing.

He contacted Brigadier General Frank Hunter, commander of the 8th Air Force’s fighter units, requesting permission to install K14 sites in a limited number of aircraft for combat evaluation. Hunter’s practical approach to military innovation made him more receptive to technological solutions than his subordinate colonels, particularly when those solutions promised to reduce American casualties while increasing mission effectiveness.

The conversation took place in Hunter’s office at High WOM, surrounded by maps showing the expanding scope of American bomber operations deep into German territory. Miller presented combat reports documenting the limitations of conventional gunnery while outlining how gyroscopic sites could address these shortcomings.

Hunter listened carefully, occasionally asking technical questions that revealed his understanding of the operational implications. The general’s primary concern focused on reliability. Would the K-14 function effectively under combat conditions, or would it fail at critical moments and leave pilots defenseless? Miller’s response drew on months of rigorous testing conducted at Wrightfield in Spar’s facilities.

The gyroscopic site had been subjected to temperature extremes, vibration loads, and gravitational stresses that exceeded anything likely to be encountered in operational use. Component failure rates remained below acceptable military standards, and the devices backup systems ensured that pilots retained conventional gunnery capability even if the gyroscopic elements malfunctioned completely.

More importantly, combat evaluation flights conducted by experienced test pilots had demonstrated consistent improvements in hit probability without compromising aircraft performance or pilot workload. Hunter’s decision to authorize limited field trials represented a crucial breakthrough for the K14 program. The general support provided the political protection necessary to overcome resistance from subordinate officers while establishing precedent for broader deployment if initial results proved successful. Hunter specified that the

trials would involve installing gyroscopic sites in 12 aircraft from the 357th Fighter Group, allowing operational evaluation under actual combat conditions while maintaining sufficient conventional aircraft to ensure squadron effectiveness. The installation process required unprecedented coordination between Spar’s technical personnel and Air Force maintenance crews.

Each K14 site demanded precise calibration to match the specific characteristics of its host aircraft, accounting for factors such as gun harmonization, ammunition weight distribution, and individual aircraft handling characteristics. The gyroscopic systems also required specialized maintenance procedures that frontline mechanics would need to master quickly, adding complexity to logistical operations that were already stretched to capacity.

Miller personally supervised the first installations, working alongside Air Force technicians to ensure proper integration between the gyroscopic sites and existing aircraft systems. The process revealed numerous compatibility issues that required improvised solutions, electrical connections that interfered with radio equipment, mechanical mounts that conflicted with existing instrumentation, optical alignments that shifted during high stress maneuvering.

Each problem demanded immediate resolution to maintain the testing schedule that Hunter had approved. The human dimension of this technological transformation weighed heavily on Miller’s mind as he watched pilots familiarize themselves with the K-14’s operation. These young men, many still in their early 20s, carried the responsibility for proving that American engineering could provide decisive advantages over enemy forces.

Their success or failure would determine not only the fate of the gyroscopic site program, but potentially the outcome of crucial air battles that were rapidly approaching as Allied invasion plans neared completion. Miller understood that the next few weeks would determine whether months of development work would translate into battlefield effectiveness or join the growing catalog of promising innovations that failed to influence the war’s outcome.

The first combat test of the K-14 came on June 2nd when Lieutenant Colonel Dutch Ryan led 12 Mustangs equipped with gyroscopic sights toward a formation of flying fortresses under attack near Magdabberg. German radar had detected the bomber stream while it was still over the North Sea, allowing Luftvafa controllers to position interceptor squadrons along the projected flight path.

By the time Ryan’s fighters reached the combat zone, 30 Messers Schmidt 109’s and Folky Wolf 198 were already engaged with the bomber formation’s escort fighters in a sprawling aerial battle that stretched across 50 mi of German airspace. Ryan spotted the first target at a range of 1,800 yd, a lone Messor Schmidt diving toward a damaged B17 that had fallen behind the main formation.

Under normal circumstances, such a long range shot would have been considered a waste of ammunition. Traditional ring and bead sights became virtually useless beyond 800 yd, particularly when engaging maneuvering targets. But the K-14’s gyroscopic tracking system maintained a steady solution, even as the German fighter executed a shallow diving turn, its yellow nose spinner growing larger in Ryan’s optical sight.

The engagement lasted less than 10 seconds. Ryan centered the Messor Schmidt in his sight’s tracking reticle, allowing the gyroscopic system to calculate deflection angles while he closed the range to 1500 yd. The K14’s mechanical computer processed the targets angular movement, combined this data with range estimates and ballistic coefficients for the Mustang’s 50 caliber machine guns, then projected the proper aiming point directly onto Ryan’s field of view.

When he pressed the firing button, six streams of armor-piercing incendiary rounds converged precisely where the gyroscopic sight had predicted the German fighter would be. The results exceeded every expectation from the testing program. Ryan’s bullet struck the Messor Schmidt’s engine, cowling and wing route, severing fuel lines and destroying critical flight controls.

The German aircraft rolled inverted and dove toward the ground, trailing black smoke and pieces of aluminum skin. The pilot never had an opportunity to return fire or execute evasive maneuvers. The engagement had ended before he realized he was under attack. Captain Dick Coker, flying wing position on Ryan’s right, witnessed the entire sequence and immediately understood its implications.

The K-14 had allowed Ryan to destroy an enemy fighter under conditions that would have made conventional gunnery impossible. The range, deflection angle, and target speed had combined to create a firing solution that human pilots could not calculate quickly enough to execute successfully. Yet, the gyroscopic site had solved the problem automatically, requiring only that Ryan maintain visual contact with his target long enough for the mechanical computer to generate an accurate solution.

The engagement pattern repeated itself throughout the morning as other pilots in the squadron discovered the K-14’s capabilities. Lieutenant Bob Harrison intercepted a Faulwolf 190, attempting to attack bombers from above, engaging the German fighter at a range of,300 yardds while both aircraft maneuvered in a climbing turn.

The gyroscopic sight tracked the target through a complete barrel roll, maintaining firing solutions that allowed Harrison to score hits with three separate bursts. The German pilot, apparently wounded by the initial attack, attempted to break off the engagement by diving toward cloud cover, but never reached safety. By noon, the 12 Mustangs equipped with K14 sights had shot down eight German fighters without losing a single aircraft.

More significantly, they had achieved these victories while engaging targets at ranges and under conditions that would have made success unlikely using conventional gunnery methods. The gyroscopic sights had effectively extended the engagement envelope for American fighters, allowing them to destroy enemy aircraft while remaining outside the effective range of defensive return fire.

The tactical implications became apparent during the mission debriefing at Lon Airfield. Ryan’s pilots reported that the K14 had fundamentally changed their approach to aerial combat. Instead of maneuvering to achieve close-range firing positions, a process that exposed them to enemy defensive fire and consumed precious time while bombers remained under attack, they could engage targets immediately upon visual contact, often destroying German fighters before the enemy pilots realized they were being engaged.

Captain Coker summarized the transformation in language that reflected years of combat experience. Sir, it’s like having a crystal ball that shows you exactly where to aim. The German pilots haven’t figured out how to counter it yet because they don’t know it exists. They’re still flying tactics designed to defeat pilots using ring and bead sights, but we’re not playing by those rules anymore.

The success generated immediate interest from other fighter groups operating in the European theater. Word of the K14’s effectiveness spread through the informal communication networks that connected American airfields across England, carried by pilots, maintenance personnel, and intelligence officers who recognized the significance of what they had witnessed.

Within days, Ryan was fielding requests from squadron commanders who wanted to know when their units might receive similar equipment. However, the enthusiasm at operational levels contrasted sharply with continued resistance within the Army Air Force’s hierarchy. Colonel Felin’s response to the combat reports reflected his fundamental skepticism about technological solutions to tactical problems.

He argued that the results from a single engagement could not justify the massive procurement and training programs that widespread K14 deployment would require. More concerning, Felin suggested that the gyroscopic sites might actually degrade long-term pilot effectiveness by creating dependence on mechanical systems that could fail at critical moments.

The debate intensified when maintenance reports revealed the first technical problems with the K14 installations. Two of the gyroscopic sites had experienced calibration drift during high stress maneuvering, requiring recalibration before they could be used effectively. Another unit had suffered component failure when exposed to extreme temperature variations during high altitude flight.

While these problems were relatively minor and could be corrected through improved manufacturing techniques, they provided ammunition for critics who argued that the devices were too complex for reliable field operation. Miller found himself caught between operational commanders who demanded immediate expansion of the K14 program and procurement officials who insisted on extensive additional testing before authorizing production increases.

The engineering challenges were manageable. Sperry’s manufacturing capabilities could support production of several hundred units per month once dedicated assembly lines were established. But the bureaucratic obstacles seemed insurmountable, particularly given the compressed timeline imposed by Allied invasion planning.

The situation was further complicated by intelligence reports indicating that German engineers were developing countermeasures specifically designed to defeat gyroscopic gun sites. Captured documents revealed Luftvafa awareness of British experiments with similar systems, suggesting that the tactical advantages demonstrated by Ryan’s squadron might be temporary.

German pilots were already experimenting with new evasive maneuvers intended to disrupt the stable tracking conditions that gyroscopic sites required for accurate firing solutions. The race between American deployment and German countermeasures added urgency to procurement decisions that were already fraught with political and technical complications.

Miller understood that the window for achieving decisive advantages with the K14 was rapidly closing. Once German pilots adapted their tactics to counter gyroscopic sites, the American advantage would diminish significantly. The question was whether institutional resistance could be overcome quickly enough to achieve meaningful deployment before enemy countermeasures neutralized the systems effectiveness.

The stakes extended beyond the immediate tactical situation. Success or failure of the K-14 program would influence post-war military aviation development, determining whether American forces would embrace sophisticated fire control systems or continue relying on pilot skill and conventional weapons technology. The decision carried implications that would shape aerial warfare for decades after the current conflict ended.