Sarah Martinez had been standing in line since 5:00 a.m. She was 19, a film school dropout working three jobs. This was her first day as an extra on a real Hollywood set. She watched the lead actors get escorted to a massive tent. Coffee, pastries, air conditioning, hair and makeup stations that looked like luxury salons.

Then she looked at the extras area. Folding chairs, warm water bottles, portaotties. Extras lineup,” the assistant director shouted. “Hair and makeup, 30 seconds each. Move.” Sarah’s heart sank. 30 seconds. The lead actor had been in the chair for 45 minutes. But what Sarah didn’t know was that Robert Redford was watching from across the lot.

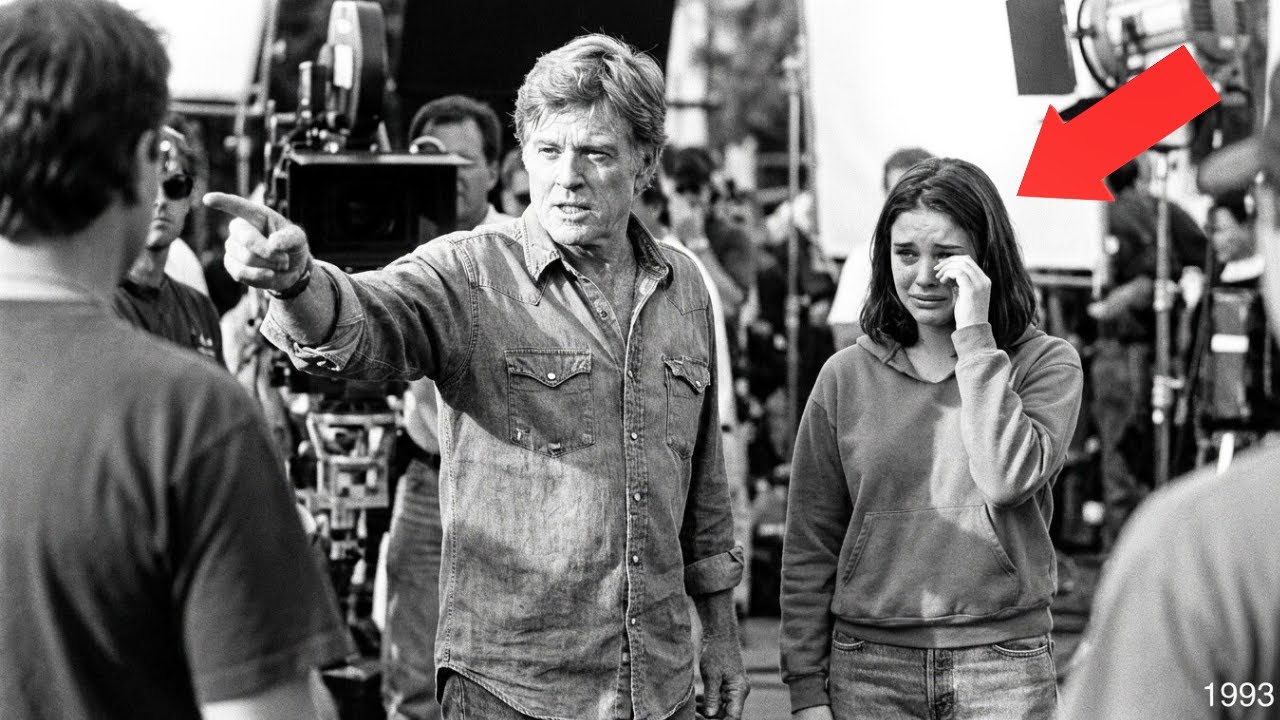

And what he did in the next 60 seconds would make her cry. Not from humiliation, but from something else entirely. To understand what happened that morning in 1993, you need to understand how Hollywood has always worked. There’s a hierarchy, a food chain. And at the bottom of that chain, invisible and expendable, are the extras. They’re called background.

Sometimes just BG. They’re the people who fill restaurants and romantic comedies, who walk past the hero in action scenes, who sit in courtrooms and laugh at sitcom jokes. They make the world look real, but to the industry, they’re not quite real themselves. They’re human props. Sarah had learned this within her first hour on set. She’d arrived at 5:00 a.m.

to the parking lot of a studio in Burbank. 200 other extras were already there, clutching their paperwork, wearing the business casual clothing they’d been instructed to bring. A production assistant with a clipboard divided them into groups. Group A, group B, group C. Sarah was group C. The lowest tier, the people who’d be so far in the background, you’d need to pause the film to see them.

Group C, you’re holding until we need you, the PA said. Could be an hour, could be 6 hours. Stay in the tent. The tent was a converted parking structure with industrial fans that barely cut through the July heat. Sarah found a folding chair and sat down. Around her, other extras pulled out books, phones, crossword puzzles.

The veterans, they knew how this worked. At 7:00 a.m., she watched the lead actors arrive, Town Cars, personal assistants. She recognized one of them, Marcus Sterling, a rising action star. He was escorted directly to a luxury trailer. At 8:00 a.m., the call came. Group C, you’re up. Hair and makeup, then to set. Sarah’s pulse quickened.

This was it, her first scene. Even if she was just a blur in the background, she was going to be in a real movie. But then she saw the hair and makeup setup for extras, one folding table, two artists, a line of 30 people. She did the math. If they had 30 seconds each, that was 15 minutes total for 30 people.

She looked over at the lead actor’s tent. Three full stations, plush chairs, ring lights, one artist per actor, working carefully, methodically. Marcus Sterling had been in the chair for 45 minutes. She’d watched him through the tent opening, laughing with his makeup artist, sipping an iced coffee someone had brought him. Next. The makeup artist’s voice snapped Sarah back. The woman looked exhausted.

Her name tag said Teresa. She’d probably been working since 5 a.m., too. Sarah sat down. Teresa barely looked at her. Powder brush. Quick swipe. Blush. Two dabs. Done. Next. 28 seconds, Sarah had counted. She stood up, looking at her reflection in the small handheld mirror on the table. The makeup was barely visible, just enough to keep her from looking washed out under the lights.

Nothing like the carefully sculpted faces of the lead actors. “Extras to set,” the assistant director called. His name was Brian Chen. Mid30s headset, clipboard, the harried look of someone managing 200 moving parts. Sarah and the other extras were herded to the set, a restaurant scene. They were given positions.

Sarah was at a table in the back, barely visible. Her scene partner was a man in his 60s who’d been doing extra work for 20 years. First time? He asked. Sarah nodded. You’ll get used to it. But what neither Sarah nor anyone else on that set knew was that Robert Redford wasn’t in his trailer. He was standing behind a equipment truck watching.

Redford was the star of this film. He was also the director. And for the past hour, he’d been observing how his set operated. He’d seen the lead actor’s luxury tent. He’d seen the extras folding chairs. He’d watched Teresa rush through 30 faces in 15 minutes. And he’d watched the exhaustion and resignation in the extra’s eyes.

Redford had started as an extra himself. 1959, New York. He’d stood in the back of theater productions, waiting for his chance. He remembered the feeling, the invisibility, the sense that you didn’t quite matter yet. He’d vowed back then that if he ever made it, he’d remember where he came from. But somewhere in the rush of fame and success, the vow had gotten buried.

His sets had operated the same way every other set operated. Stars and trailers, extras and tents. That’s just how it worked until today. until he’d watched a 19-year-old girl get 28 seconds of makeup while his co-star got 45 minutes. Something in him cracked. Redford walked across the lot toward Brian Chen.

His face was calm, but his jaw was tight. Everyone who’d worked with Redford knew that look. It meant something was about to change. “Brian,” Redford said quietly. “We need to talk.” Brian turned, expecting a question about the shot list or the schedule. Instead, Redford gestured toward the extras area.

How much time did they get for hair and makeup? Brian blinked. Uh, the usual, about 30 seconds each. And how much time did Marcus get? I I don’t know. 45 minutes. Standard for leads. Redford nodded slowly. Standard, right? He paused. We’re changing the standard. Brian’s face went pale. What do you mean? I mean, everyone on this set, lead, supporting, extra, gets the same treatment, same quality hair and makeup, same food, same respect.

Brian stammered. Bob, that’s that’s not how it works. We don’t have the budget. We don’t have the time, then we’ll make time, Redford said. And we’ll find the budget because I’m not directing a film where people are treated like they don’t matter. Brian looked around desperately. But the schedule, we’ll fall behind.

Then we fall behind. Redford’s voice was quiet but absolute. Call everyone to the set. Leads, crew, extras, everyone. Brian hesitated. Redford waited. Finally, Brian lifted his radio. All personnel to the main set. All personnel. 5 minutes later, 150 people stood on the restaurant set, confused. Worried.

The extras were especially nervous when production stopped unexpectedly. Extras were usually the first to be sent home. Redford stood in the center. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to. I’ve been watching how this set operates, he said. And I’ve realized something. We’ve built a system where some people matter more than others.

Where some people get 45 minutes of care and attention and some people get 30 seconds. He paused. The set was completely silent. That ends today. He turned to Teresa, the makeup artist. How many artists do we have for the leads? Three, Teresa said. And for everyone else? Two. Redford nodded. Hire three more.

And going forward, every single person on this set gets the same quality treatment. I don’t care if you’re the star or you’re sitting at a table in the background. You’re part of this story. You matter. He looked at Brian. change the call times. If we need to start earlier to give everyone proper preparation, we start earlier. If we need to extend the shooting schedule, we extend it.

But nobody on my set gets treated like they’re less important than anyone else. The silence stretched. Then Marcus Sterling, the lead actor, stepped forward. Bob, I’ll give up my trailer time. If it means everyone gets treated fairly, I’ll come in earlier. Another actor nodded. Me, too. Teresa, the makeup artist, had tears in her eyes. Mr.

Redford, do you know how long I’ve wanted someone to say that? Redford smiled gently. How long? 15 years. The set was still silent. Then someone started clapping. Then another person. Within seconds, 150 people were applauding. Sarah, standing at the back, felt tears running down her face. Not from humiliation this time, from the sudden overwhelming realization that she’d just witnessed something that never happened in Hollywood.

Someone with power had used it to lift people up instead of maintaining the hierarchy. But Redford wasn’t done. He walked over to the extras section directly to Sarah. What’s your name? Si Sarah. She managed. Sarah Martinez. Sarah, you were first in line this morning for hair and makeup. Is that right? She nodded. Yes, sir.

Then you’re first in line for the new system. Come with me. Redford led Sarah to the lead actor’s tent. Teresa followed, carrying her kit. Redford gestured to the plush chair Marcus had been using. Have a seat. Sarah sat down, trembling. The chair was heated. There were bottles of sparkling water. A ring light illuminated her face.

Teresa stood behind her and for the first time all day she smiled. Really smiled. “Okay, Sarah,” Teresa said. “Let’s do this right.” For the next 30 minutes, Teresa worked on Sarah’s face. Carefully, thoughtfully, asking questions. “What’s your skin type? Do you like dramatic eyes or natural?” She treated Sarah the same way she treated Marcus Sterling that morning, like she mattered, like her face deserved care and attention.

When Teresa finished, Sarah looked in the mirror. She looked beautiful, not invisible. Not like background, like someone. “Thank you,” Sarah whispered. Teresa squeezed her shoulder. “Thank you,” Teresa whispered back. The rest of the day ran long. very long. Redford’s new policy meant that instead of 15 minutes for 30 extras, it took 6 hours.

The shooting schedule collapsed. They didn’t finish half the scenes they’d planned. Brian spent the day on the phone with the studio explaining, apologizing, rescheduling. But something else happened that day. The atmosphere on set changed. The extras weren’t invisible anymore. Crew members started learning their names.

The lead actors sat with them during breaks. Sarah found herself in a real conversation with Marcus Sterling about film school, about dreams, about the industry. I started as an extra, too. Marcus told her, “Nobody remembers that now, but I do. And what Bob did today, I’ve been in this industry 10 years, and I’ve never seen anyone do that.

” At the end of the day, as the sun was setting and the set finally wrapped, Redford gathered everyone again. “I know today was chaos,” he said. I know we’re behind schedule. I know the studio is not happy with me right now. A few nervous laughs. But I’m not sorry because today we built something better. We built a set where everyone matters.

Where respect isn’t rationed based on billing. He looked at the extras. Some of you are at the beginning of your careers. Some of you have been doing this for decades. Either way, you deserve to be treated with dignity. And on my sets, from now on, you will be. The applause came again, longer this time, louder.

Not just for the policy change, but for something deeper, for the feeling so rare in Hollywood that someone in power actually gave a damn about the people at the bottom. Sarah went home that night with her carefully done makeup still on. She didn’t want to wash it off. She wanted to remember how it felt to be seen, to matter.

3 months later, she got her first speaking role. A year after that, she was cast in a supporting part in an independent film. Five years later, she directed her first feature. She never forgot that day in 1993. And every set she worked on after that, whether as an actress or a director, she made sure everyone got the same treatment, stars and background actors, lead and extra, because Robert Redford had shown her that respect wasn’t about hierarchy. It was about humanity.

The story of what Redford did that day spread through Hollywood. Some directors adopted his policy, others ignored it. The industry didn’t change overnight, but something shifted. A seed was planted. The idea that maybe, just maybe, the people in the background deserved to be seen. Teresa, the makeup artist, retired in 2015.

In her final interview with a film industry magazine, she was asked about her favorite moment in 40 years of working in Hollywood. She didn’t mention the A-list stars. She didn’t mention the blockbusters. She mentioned a morning in 1993 when Robert Redford stopped production and said three words that changed her career.

Everyone gets respect. I’d been doing 30 secondond Faces for 15 years. Teresa said, “I was so tired. I felt like I was on an assembly line. And then Bob Redford showed me that my work mattered, that those faces in the background mattered. He gave me back my dignity. and he gave it to every extra on that set.

In 2018, the Screen Actors Guild updated its guidelines for treatment of background actors, minimum standards for working conditions, meal quality, and preparation time. It wasn’t enough. There’s still a hierarchy, still inequality. But it was progress. And according to several union reps, the movement toward better treatment of extras can be traced back to a handful of directors who refused to accept the old system.

Robert Redford was the first. Sarah Martinez, now a successful director herself, includes a note in all her production contracts. It’s simple. It reads, “All personnel, regardless of role size, will be treated with equal respect and dignity. No exceptions.” When asked about this policy, she always tells the same story.

The story of her first day as an extra. The story of 28 seconds of makeup and 30 minutes of transformation. The story of the day, Robert Redford stopped everything and said that respect wasn’t something you earned with fame. It was something every human being deserved from the moment they walked on set.

He didn’t just change my career, Sarah says. He changed how I see people, how I treat people. He taught me that power is worthless if you don’t use it to lift others up. That’s the real legacy of what happened on that set in 1993, not the film they were making. Most people don’t even remember what it was called.

But the moment, the decision, the refusal to accept that some people matter more than others. Robert Redford could have stayed in his trailer that day. He could have looked away. It would have been easier. It would have kept the schedule on track. It would have kept the studio happy. But he didn’t look away.

He saw a 19-year-old girl getting 28 seconds of makeup while the star got 45 minutes. And he decided that wasn’t acceptable. He used his power, his platform, and his privilege to say, “Not on my set.” That’s not just good directing. That’s leadership. That’s humanity. That’s what happens when someone with a voice chooses to speak up for the people who don’t have one.

The next time you watch a movie, look at the people in the background, the ones sitting in the restaurant, the ones walking on the street, the ones filling the stadium seats. Someone woke up at 4:00 a.m. to be there. Someone stood in line. Someone waited in a tent, hoping to matter, if only for a moment. Robert Redford saw those people and he decided they mattered, not just in the scene, but in life.

That’s the story of the Day Film crew treated extras like trash. And Robert Redford’s response made the entire set applaud. It’s a reminder that respect isn’t about hierarchy. It’s about humanity. And the people who change the world aren’t the ones who climb to the top and pull the ladder up. They’re the ones who reach down and pull others up with