Bigfoot Saved Me From Falling into Frozen Lake, Then It Did Something Strange

I never thought I would owe my life to a Bigfoot.

That sentence still tastes ridiculous when I say it out loud—like something you’d hear whispered at a bar by someone who’d had too much to drink. But three winters ago, up in northern Michigan, it stopped being a crazy idea and became the truest thing I know.

I fell through the ice on a lake I’d fished since I was a kid.

And something that should not exist reached into black water, grabbed the back of my coat, and dragged me out like I weighed nothing.

What came after was stranger than the rescue. If it had pulled me free and vanished, I might have convinced myself it was panic, adrenaline, a shadow that my brain dressed up as a legend. But it didn’t leave.

It stayed with me for almost two full days.

And in that time, it showed me things I can’t explain without sounding insane—structures, tools, symbols, and a kind of careful, deliberate intelligence that didn’t belong to any animal I’ve ever known.

I’m telling this now because the story isn’t really about a monster in the woods.

It’s about a mistake, a mercy, and a secret that was placed in my hands the way a fragile object is placed in someone you decide—quietly—to trust.

1) Friday Afternoon, Late January

I drove up on a Friday in late January, the kind of winter week where the cold has been steady for so long you start to believe the world will stay frozen forever.

Three weeks below freezing, the forecasts said. That was enough for me. The lake sat about an hour north of where I live, tucked back in the woods with a single access road and lousy cell service—the perfect place if you wanted to disappear for a weekend without anyone demanding anything from you.

The parking area by the boat launch was empty. No other trucks. No steam rising from heaters. No silhouettes on the ice. Just snow piled along the edges where the county plow had pushed it aside.

There were tracks, though—snowmobile grooves and deer prints along the trail down to the water. Evidence that life had passed through recently and left no explanation beyond pattern.

I loaded my gear onto my plastic sled: pop-up shelter, gas auger, rods, tackle, cooler. I wore my ice cleats. I wore my picks around my neck. I’d learned years ago to take solo ice fishing seriously, because out here one mistake can turn into a disappearance no one understands until spring.

The walk to the lake was five minutes through thick pine with birch and oak mixed in. Everything was white and quiet in that perfect postcard way. A woodpecker hammered somewhere deep in the trees. Chickadees hopped between branches like little scraps of moving life.

When I stepped onto the ice, it looked solid.

That’s the first lie ice tells you: it always looks solid, right up until it isn’t.

I walked about two hundred yards out to a spot over deeper water, where I’d caught decent pike and perch before. Snow on top was four inches, wind-swept in places. Everything felt normal. Everything felt familiar.

I set up my shelter, marked out three holes in a triangle, and fired up the auger.

The sound of it tore through the quiet.

Looking back, I think that’s part of what doomed me: the way noise convinces you you’re in control. If the machine is working, you believe the world is behaving.

The blade bit into the ice. White chips flew up. I watched them scatter and didn’t register what my brain should have registered immediately:

The chips were wet.

The ice had a gray tint instead of clear blue.

I drilled anyway.

The auger broke through after about eight inches.

Eight.

That should have been enough to make me pack up and move closer to shore, to shallower water, to safety. Eight inches can be fine under certain conditions, but “fine” becomes a gamble when there’s current, springs, or uneven freeze-thaw.

I had driven an hour.

I wanted to fish.

So I ignored the warning.

And the lake took that personally.

2) The Crack That Became a Line

The first crack was quiet—like a branch snapping somewhere far away. I stopped drilling and listened.

Wind slid through the pines. The lake made its occasional groan, the sound ice makes when it expands and contracts and nobody is there to hear it but you.

I told myself it was normal settling.

I went back to drilling.

The second crack was louder. Closer.

The ice shifted under my boots—not much, just enough to drop my stomach as if the ground had briefly forgotten it was supposed to hold me.

I looked down.

A thin line had opened in the ice between my feet.

It spread outward in both directions with little running snaps, spidering faster than thought.

That’s the moment your body understands before your mind catches up: You are standing on a mistake.

I dropped the auger and tried to do what you’re taught—spread your weight, go flat, don’t fight the ice like it’s land.

But I was too slow.

The ice broke under my left foot and I went down to my knee.

Cold water hit my leg like a slap, shock so sharp it stole my breath.

Then the ice broke again, and I was waist deep, then chest deep, then suddenly the world flipped and I went under completely.

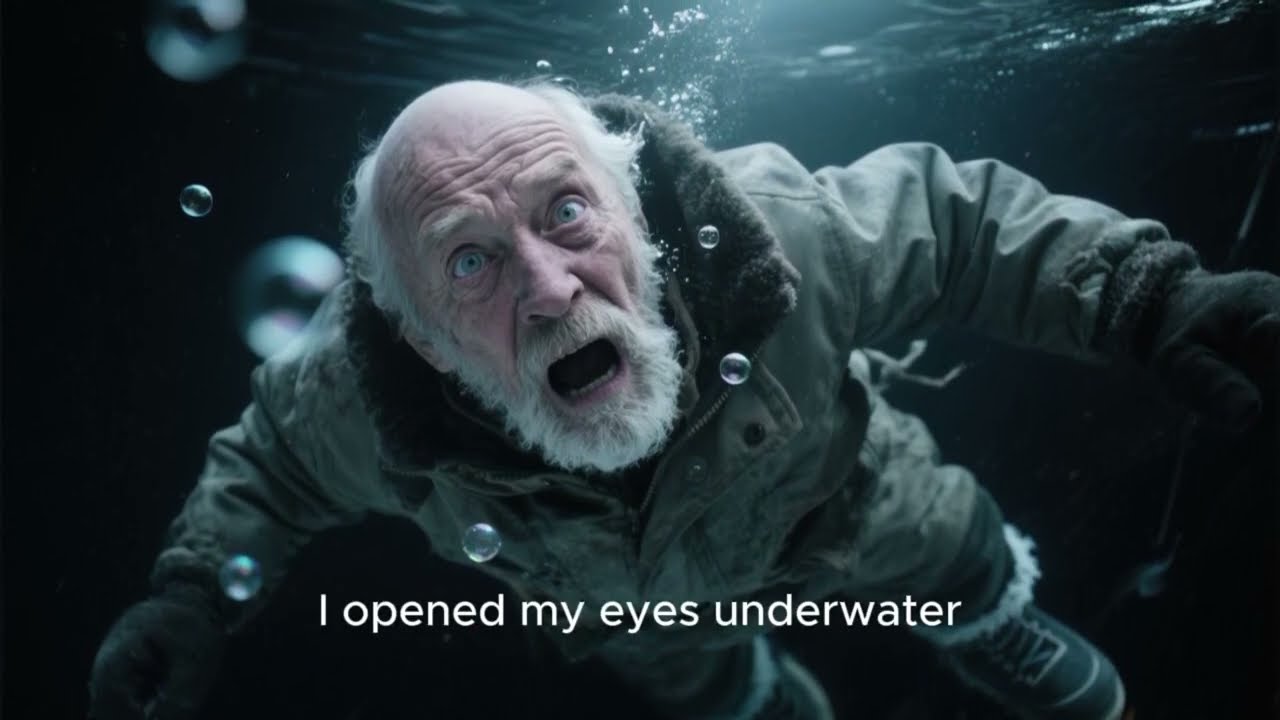

3) Black Water, No Direction

There are people who talk about cold water like it’s “uncomfortable.”

That isn’t what it is.

It’s an attack. A physical force that grabs your lungs and tells your body, violently, that you don’t belong here.

The cold knocked the air out of me. Muscles seized. My winter gear became an anchor—coat and boots filling, dragging me down. I tried to kick, but my legs moved like they belonged to someone else.

I opened my eyes.

Darkness.

No up. No down. No reference point. Just the black under-surface of the ice above me, smooth and deadly, like the ceiling of a tomb.

My hand hit that ceiling and I pushed hard, searching for the hole I’d fallen through.

But current moved me sideways.

I scraped my fingers along the underside, frantic, looking for an edge, a break, any texture that meant “exit.”

Nothing.

Just ice in every direction.

My lungs began to burn. That particular burning that isn’t pain so much as your body screaming air now and preparing to take it whether you want it or not.

Black spots crawled across my vision.

I had seconds.

And then something grabbed the back of my coat.

Not my wrist. Not my hand.

My coat—right between the shoulder blades—like a hand that understood exactly how to lift a drowning man without losing him.

I rose fast, too fast, and broke the surface coughing and choking.

Cold air sliced in.

I was being dragged.

Across ice, scraping, moving away from the hole like the thing pulling me knew that thin ice doesn’t stop breaking just because you’ve survived once.

Then the dragging stopped.

I was on the shore, half on snow, half on churned ice, coughing water out of my lungs and shaking so violently my teeth clacked like tools.

My eyes blurred, watering from cold and shock.

I blinked hard.

And looked up.

4) The Shape Over Me

It stood over me, massive and still, filling the world.

Eight feet tall, maybe more. Thick reddish-brown hair, longer and shaggier around the shoulders and arms. Legs planted wide in the snow like it didn’t need balance the way I did.

And the face—

Not a bear’s face. Not an ape’s face. Not a costume face.

Flatter than a gorilla’s, more human in proportion without being human. Broad flat nose. Heavy brow that shadowed the eyes. Mouth closed, wide, serious.

Its eyes were dark brown—almost black—and they looked directly into mine.

Not empty.

Not wild.

Aware.

It breathed heavily, steam rising from nose and mouth, chest lifting and falling with the exertion of what it had just done.

I couldn’t process it. My brain tried to find the nearest category: hunter. rescuer. man.

But nothing fit.

The creature made a low grunt, not aggressive—more like a check, a question: Are you alive?

I tried to speak. My jaw wouldn’t cooperate. My whole body was shaking too hard.

After a few seconds, it turned and walked into the trees.

It moved fast despite its size, disappearing between trunks like the forest had parted for it.

For a heartbeat, I thought: That’s it. I hallucinated. The shock made a story. It’s gone.

Then reality returned with the cruelest reminder.

I was soaked.

And the air was ten degrees.

If I didn’t get out of wet clothes and build heat, I’d survive drowning only to die of hypothermia within sight of the lake.

My fingers were already numb, clumsy, refusing to obey.

I started fumbling with my coat.

And heard movement behind me.

5) Birch Bark and Intention

It came back.

And it wasn’t empty-handed.

It carried an armload of dead branches and sheets of birch bark—the pale kind that lights fast even when everything else is stubborn.

It approached slowly, dropped the wood about three feet from me, then stepped back and watched.

I stared at the pile. Then at it.

The branches were dry. Not random. Not green. Selected.

The bark was clean, thin, perfect tinder.

This wasn’t instinct.

This was planning.

It made that low grunt again and gestured toward the wood with one massive hand.

Clear as a spoken sentence.

Build a fire.

I nodded, because nodding was all I had.

Somehow my lighter had stayed dry in a waterproof pocket. My shaking thumb fumbled the wheel. Once. Twice. Three times—nothing. Fourth—spark, gone. Fifth—flame.

I shredded birch bark into curls, touched flame to it, and watched it catch like a promise. I fed it twigs, then small sticks, then larger ones.

The fire grew.

Warmth rolled toward me, and I held my hands over it so close it almost hurt.

Feeling returned in painful pins and needles. My face was numb. Ice crystals clung to my beard. My pants were freezing stiff.

I needed to strip.

So I did.

Right there on the shore, down to my underwear, moving fast and clumsy, hanging wet layers on branches to dry, rotating boots close to coals, careful not to ruin leather.

The whole time, it watched—not like a predator watching prey, but like someone guarding a patient.

It didn’t come closer.

It didn’t threaten.

It simply stayed present, as if that presence itself was a kind of shelter.

Then it turned and walked back into the forest again.

And this time I didn’t know whether to feel relieved or abandoned.

6) The Second Trip: Enough for the Night

It was gone maybe ten minutes.

I used the time to check for frostbite—especially toes. White and numb doesn’t always mean damage, but it’s the color that starts fear.

I held my feet toward the fire and waited for pain, because pain would mean blood returning.

Then it returned—carrying bigger wood.

Larger pieces, enough to keep fire alive for hours.

It stacked them neatly near the fire, then did something I still think about when people claim Bigfoot is just an animal:

It sat down.

Fifteen feet away. Cross-legged. Facing me.

Not “collapsed” down. Not flopped. Sat with surprising grace, brushing snow aside first like it cared about comfort.

Then it went still—alert still, patient still.

Watching.

Night came down slowly, the sky turning purple and then black, stars sharp and numerous, the kind you don’t see near city light. The lake groaned as the cold tightened it. Wind whispered through pines.

I tried talking. Thank you, again and again. My name. Questions. Nonsense. Anything to fill the space between terror and wonder.

It didn’t respond with words.

But it listened.

I could tell by the way its eyes tracked me, by the small head tilts, by the subtle shifts that said my voice mattered even if it didn’t understand language the way I did.

Around midnight, I started to sag with exhaustion.

I was afraid to sleep. Afraid the fire would die. Afraid something else would come out of the trees. Afraid it would leave.

As if reading that fear, it stood, walked to the woodpile, and placed thick logs onto the fire to make it burn longer.

Then it returned to its spot and sat again.

A simple act that said: I am not leaving.

I dozed off anyway, because the body always wins.

7) Follow Me

I woke to something shaking my shoulder.

I jerked upright, heart hammering, and saw it crouched close—closer than before.

The fire had burned down to coals.

It made a grunt, stood, and gestured for me to follow.

Then it walked into the forest and paused after a few steps, looking back like it was checking whether I understood.

Every rational part of my brain screamed that following an unknown eight-foot creature into the dark was a terrible idea.

But it had pulled me from black water.

It had brought tinder.

It had fed my fire while I slept.

So I stood and followed.

It moved slowly, ensuring I could keep up on shaky legs. We walked uphill for twenty minutes through thick trees.

And then we entered a clearing I had never seen before—half an acre, sheltered, positioned like someone had chosen it with care.

In the center were structures.

Not fallen branches.

Not natural windfall.

Built shelters.

Three dome-shaped forms made from branches, bark, and leaves woven together like giant baskets, each large enough for something its size to sleep in. Positioned in a triangle, spaced about twenty feet apart, tucked beneath overhanging pine branches for extra protection.

Homes.

My mouth went dry.

I was staring at proof of something the world insists doesn’t exist: not an animal den, but construction.

It walked to the nearest shelter, pulled back the entrance covering, and gestured for me to look.

Inside was a thick mat of dried grass and moss—six inches deep—layered and woven for insulation. Not thrown in. Arranged. Built like bedding.

It watched my face as I took it in.

And I swear, in that moment, it looked… proud.

It brought me to the second shelter—larger, entrance facing east toward sunrise. Draft-blocking bark placed with intent. Stones positioned where hot coals could be brought in for heat.

Then the third: smaller, packed with storage—bundles of plant fiber, rolled hides, stacks of bark, organized moss.

Organization is not a wilderness accident.

It was showing me a life.

8) Tools, Bones, and a Language Without Paper

In another part of the clearing, there were rocks stacked in a purposeful way and deer bones arranged by size.

Tools.

It picked up a smooth granite piece and mimed scraping against a log—hide processing, perhaps, or shaping wood. Then a hammer stone. Then a sharpened bone tool for digging or prying. Then a bone split lengthwise—sharp edge for cutting.

Nearby lay sticks prepared in different ways: bark stripped, one end charred to harden, notches cut in patterns that didn’t look random.

It held up one stick with deep grooves and ran its thumb along them, then looked at me like it expected recognition.

I had none to give.

But I remembered the grooves.

Because something about them felt like information.

Then it walked me to an oak tree at the clearing’s edge.

Carved into the trunk, about seven feet high, were symbols—lines, curves, circles, marks too deliberate to be claw scratches.

It touched one, then another, then another—in a sequence.

Like reading.

Or teaching.

As it touched each mark, it made a different sound—low grunts, huffs, something that almost sounded like speech broken into pieces.

I stood there staring at the tree like it was a door.

And for the first time, I felt the real weight of what I’d stumbled into:

If this was a writing system—if these were records, names, warnings, stories—then this was not a lone creature.

This was culture.

It led me to a small stream running along the clearing’s edge, unfrozen because it moved fast. Stones were arranged into a kneeling platform. It demonstrated drinking, then gestured for me to try.

I cupped water and drank—cold, clean, sharp.

It made an approving grunt.

There was a fire pit too: blackened stones in a circle, a stack of good wood sheltered under bark.

I’d already seen it understand fire. Now I was seeing it had a place for fire, a practice of fire, a memory of fire.

As the sky began to lighten, it led me to another shelter and pulled back the covering.

Inside, on moss, lay a collection—objects arranged with care.

A blue glass bottle, worn smooth by age. Shiny stones—quartz, mica, obsidian. A bird skull perfectly white. Bundled feathers bound with twisted plant fiber, knotted with decorative purpose.

It picked up the bottle and held it to the rising light.

The glass glowed blue, and the creature turned it slowly the way a person turns something precious.

Then it set it down in the exact same place.

Art.

Not survival.

Appreciation.

It handed me a quartz crystal.

Heavy in my palm. Cold. Beautiful.

I turned it like it had turned the bottle, watching light break through it.

When I gave it back, it replaced it carefully among its treasures.

Then it picked up the feather bundle—seven large feathers, rust-colored with white tips, bound in dark plant fiber.

And it placed them in my hands, folding my fingers around them gently.

A gift.

I tried to give them back immediately, shaking my head, trying to communicate too precious.

It pushed my hand away—firm, final.

The feathers were mine now, whether I felt worthy or not.

I tucked them carefully inside my coat, close to my chest.

It made a pleased, almost purring sound.

Then it pulled out a strip of soft leather with small objects attached—an animal claw, a rounded stone, a piece of amber with something trapped inside.

It showed it to me, but didn’t offer it.

That was personal. Jewelry. Identity.

It wasn’t just showing me tools.

It was showing me selfhood.

9) The Calls in the Trees

We stayed in the clearing for hours. Light grew. Details sharpened.

Paths worn in the snow between shelters. A tree stripped of bark at eight-foot level, likely for scratching. Marks at varying heights on trunks—territory, maintenance, habit.

Then it stood and made calls louder than before.

Not threat calls.

Contact calls.

An answer came from deeper in the forest. Then another from a different direction. Then another.

Multiple voices.

My skin tightened.

Not fear of attack—fear of being somewhere I wasn’t supposed to be when others arrived.

It looked at me and gestured toward the edge of the clearing—the direction we’d entered.

Time to go.

I nodded. I understood.

It had shown me this place, but it wasn’t mine to occupy. It had taken a risk already. It wasn’t going to ask its group to accept that risk too.

Before we left, I wanted to return the gift in some way a Bigfoot would actually value.

I pulled out my pocketknife—Swiss Army, good quality, fifteen years of use, familiar weight. I held it out.

It took it carefully.

Then—this is the part people always doubt—it figured it out.

Those massive fingers opened the blade, tested the edge, opened another tool, worked the scissors, explored each implement with patient curiosity. The can opener puzzled it until I mimed opening a can. The screwdriver made sense immediately.

It wasn’t just holding a human object.

It was learning it.

When it finished examining each tool, it closed the knife and gripped it as if it understood its worth.

Then it placed a hand on my shoulder and squeezed once—gentle, heavy, unmistakable.

We walked back through the forest by a different route. It brought me to a logging road I recognized.

The road would lead me back to my truck if I followed it south.

It stopped at the tree line.

Turned to face me.

And for a moment, everything was quiet except our breathing.

I wanted to thank it in a way that meant something beyond sound.

So I reached into my pocket again and pulled out my grandfather’s pocket watch.

Old windup. Silver. White face. Roman numerals. It had been my grandfather’s daily companion until the day he died. I’d carried it for ten years after, keeping it wound because it felt like keeping him close.

I held it out.

It stared at the watch, then at me, questioning.

I opened it, showed the moving hands. Held it to its ear so it could hear the ticking.

Its eyes widened—just slightly. Not like a cartoon, but like a mind encountering a mechanism it hadn’t imagined.

It took the watch with extraordinary gentleness, studied the motion, turned it over to look at the engraved initials, then closed it and held it in its palm as if weighing its history.

Then, softly, it tucked the watch into the thick hair on its chest like a pocket.

Close.

Safe.

And it did something that turned my knees weak for reasons that had nothing to do with cold:

It pulled me into a brief, careful embrace.

Ten seconds—human and Bigfoot—arms not quite reaching around, but trying anyway.

Then it stepped back, placed a hand gently on top of my head, and held it there for a few seconds.

A blessing. A marking. A goodbye.

Then it turned and walked into the trees.

Gone.

Just like that.

10) The Return to a World That Would Laugh

I walked the logging road in a daze. Found my truck where I’d left it. Sat behind the wheel for a long time without starting the engine.

I’d spent almost two days with something the world says is myth.

It saved my life.

It kept me alive.

It showed me its home.

And it gave me a gift.

I drove home and told nobody. The only proof I had were feathers that could be explained away as “found,” and memories that sounded like hypothermia-fueled fantasy.

I didn’t go back to the clearing. Not even once.

Curiosity is a form of hunger, and hunger makes people careless. I didn’t want to be the reason someone found that place. I didn’t want to be the doorway that let the wrong kind of humans in.

So I kept the secret.

And I tried to live like a person who’d been given something sacred.

11) Six Months Later: The Marker

Half a year passed.

I was hiking in a different part of the state, nowhere near that lake—fifty miles away at least—on a trail I’d never walked before.

Around a bend, I saw stacked rocks on the side of the path.

Three flat stones balanced carefully with a round stone on top.

My throat went dry.

I’d seen that exact pattern in the clearing.

I looked around but saw nothing.

Then I heard it—off to my left, deeper in the trees.

A low grunt.

The same sound.

I turned and glimpsed something large and brown moving between trunks maybe a hundred yards away.

There for a second. Gone.

Over the next mile I found two more rock markers, each one placed where I’d notice. Each time, the forest felt… attentive.

At a trail split, a marker pointed left. I’d planned to go right. I followed the marker instead, because some part of me recognized the old dynamic: follow, and you’ll be shown something.

The left fork led to an overlook I didn’t know existed.

A valley stretched out below—untouched forest for miles, the kind of view that makes you understand why some places deserve to remain unclaimed.

I stood there, wind in my face, and felt something like grief for all the wild places already lost.

When I turned to leave, something sat on a rock beside the trail.

My grandfather’s watch.

I picked it up with shaking hands.

It was still ticking.

Not only had it returned the watch—it had kept it wound.

It looked cleaner than when I’d given it away, as if it had been cared for.

I wound it again and held it to my ear. The steady ticking sounded impossibly normal in a moment that felt anything but.

I looked into the trees and whispered a thank you, because the words had to go somewhere.

No answer came—only wind and distant birds.

But the air felt like it was listening.

And that was enough.

12) What I Carry Now

I keep the watch running. I wind it every morning the way my grandfather did… and the way I believe the Bigfoot did while it held it.

The feathers are in a shadow box on my wall. I look at them sometimes when the world feels too flat, too explainable, too loud.

I still hike. I still fish. I still love winter in the way only someone who’s nearly died in it can love it—respectful, alert.

And sometimes, in places I’ve been a hundred times, I see markers I swear weren’t there before. A stack of rocks that balances too carefully. Branches woven in a way wind doesn’t weave.

I don’t tell people. I don’t photograph them. I don’t post coordinates.

Because here is what I learned in those two days:

If Bigfoot exists the way I saw it exist, then it stays hidden for reasons that make sense.

Not because it’s mindless.

Because it’s intelligent enough to know what humans do to what we “discover.”

We put it in cages of attention. We turn it into content. We send crowds where silence was the point.

That clearing—those shelters, tools, symbols, and curated treasures—felt like a home that had been loved for a long time.

And the Bigfoot showed it to me on its own terms, in a moment of crisis, like a person revealing a private room to someone who has proven they can be trusted.

I didn’t earn that trust.

I was given it.

So I keep the secret.

And if you ever find yourself alone on winter ice, or deep in woods where the world goes quiet in that particular way, remember this:

Sometimes help comes from places you weren’t taught to believe in.

And if it does—if you’re lucky enough to be pulled back from the edge—don’t repay that gift by turning it into a spectacle.

Some mysteries survive only because someone chooses respect over proof.

That’s the promise I made.

And it’s the reason I’m alive to tell the story at all.