August 1943, the Quadrant Conference, Quebec City. President Roosevelt stares at reconnaissance photos spread across the mahogany table. 100,000 Japanese soldiers, fortified behind concrete bunkers and artillery positions that turn Rabal into the most heavily defended base in the Pacific. Every military adviser in the room knows what comes next. Another Terawa.

Another blood bath on the beaches where American Marines charge into machine gun fire. The math is brutal. Estimated casualties. 30,000 Americans dead or wounded. Maybe more. General MacArthur slides a different map across the table. His finger traces a circle around Rabal. Not through it. We don’t take the fortress, he says quietly. We starve it.

The room goes silent. In the corner, Admiral Holsey shifts uncomfortably. Everything they’ve been taught about warfare says you destroy the enemy’s strongest position first. You don’t leave it alone. But MacArthur’s plan defies every rule in the book. Instead of sacrificing 30,000 American lives to capture Rabal, the US will capture the islands around it.

Cut off every supply ship, every transport plane, every grain of rice. Roosevelt nods slowly. The decision that will trap 100,000 Japanese soldiers behind their own defenses, turning Japan’s greatest Pacific stronghold into the world’s largest prison. The conference room fell silent as Roosevelt’s pen hovered over the operational orders. Outside, the St.

Lawrence River carved through Quebec City like a silver ribbon. But inside, the weight of 100,000 lives pressed down on every man present. MacArthur’s proposal had shattered conventional military thinking in a single sentence, and now the president of the United States had to decide whether genius or madness would guide American strategy in the Pacific.

Admiral Ka leaned forward, his weathered hands gripping the edge of the mahogany table. General, you’re asking us to leave the strongest Japanese fortress in the Pacific completely untouched. Rabul has five operational airfields, a natural harbor that can shelter their entire combined fleet, and enough concrete fortifications to stop every shell we can throw at it.

” His voice carried the skepticism of a man who had spent four decades learning that in warfare, you destroyed what threatened you most. MacArthur remained motionless, his piercing eyes fixed on the reconnaissance photographs scattered before them. Simpson Harbor at Rabbal could accommodate 50 major warships. The surrounding volcanic ridges bristled with anti-aircraft guns, coastal artillery, and interconnected bunker systems that had taken 2 years to build.

Intelligence estimates suggested the Japanese had poured more concrete into Rabol’s defenses than they had used in the entire Ziggfrieded line. Admiral,” MacArthur replied, his voice carrying the measured confidence of a man who had revolutionized warfare in the Philippines. “Were not, leaving it untouched, were turning their greatest asset into their greatest liability.

” The strategy MacArthur outlined defied every principle taught at West Point and Annapolis. Instead of launching a frontal assault against Rabul’s impregnable defenses, American forces would execute a series of leapfrog operations, capturing airfield sites on Bugganville, the Admiral T Islands, and New Britain’s Western Peninsula.

Each captured island would become a stepping stone, bringing American bombers closer to Rabol while simultaneously choking off Japanese supply routes. Roosevelt studied the proposed timeline. Operation Cartwheel would begin in June 1943 with simultaneous landings in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea.

By November, American forces would establish airfields on Buganville, placing Rabal within range of daily bombing runs. The Admiral T Islands would fall by February 1944, completing the noose around Japan’s South Pacific stronghold. “How long?” Roosevelt asked, his finger tracing the supply routes marked in red ink across the Pacific chart.

Before they’re completely cut off 90 days after we take Manis Island, MacArthur answered without hesitation. Every ton of rice, every gallon of aviation fuel, every artillery shell has to reach Rabal by sea or air. We’ll control both. The general’s aid produced a logistics analysis that laid bare Japan’s vulnerability.

Rabbal consumed 4,000 tons of supplies daily, food for 100,000 soldiers, fuel for hundreds of aircraft, ammunition for coastal guns that hadn’t been tested in actual combat, cut those supply lines, and the fortress would devour itself from within. General Marshall, who had remained silent throughout the presentation, finally spoke.

His question cut to the heart of American military doctrine. Douglas, what happens to our timetable for taking Japan if we spend 18 months strangling Rabal instead of six months capturing it? The chief of staff’s concern reflected the broader strategic picture. Every month spent isolating Japanese forces in the South Pacific was another month of delay in the drive toward Tokyo.

American industrial production could sustain prolonged operations, but public support for the war depended on visible progress toward victory. MacArthur’s response revealed the deeper brilliance of the bypass strategy. George, we’re not just neutralizing Rabal. We’re demonstrating to every Japanese garrison commander from Tru to the Philippines that their supply lines can be severed at will.

When we approach their next stronghold, they’ll know what isolation means. They’ll know their emperor cannot save them. The psychological warfare aspect of operation cartwheel had never been explicitly planned, but MacArthur recognized its potential impact on Japanese morale throughout the Pacific. Admiral Hollyy, whose South Pacific forces would bear the brunt of the initial operations, raised a practical concern that had haunted American planners since Guadal Canal.

General, my pilots have been flying combat missions for eight months straight. They’re exhausted, and replacement aircraft are arriving faster than replacement pilots. The human cost of sustained air operations over hostile territory was becoming painfully clear. Every bombing run against Japanese positions meant exposure to anti-aircraft fire, fighter interception, and the constant risk of mechanical failure over hundreds of miles of ocean.

The discussion turned to the darker implications of MacArthur’s strategy. 100,000 Japanese soldiers trapped at Rabal would face a slow deterioration of their fighting capability as supplies dwindled and equipment failed without replacement parts. Unlike the quick resolution of a traditional siege, the bypass approach condemned enemy forces to months of declining effectiveness punctuated by daily bombing raids they could not prevent or escape.

It was warfare by attrition elevated to a strategic level and its moral implications troubled some of the officers present. Roosevelt’s decision came after 3 hours of debate that ranged across logistics, strategy, and the fundamental nature of modern warfare. The president had watched American casualties mount through North Africa, Sicily, and the early Pacific campaigns.

Every invasion carried a terrible arithmetic. How many young men would die to achieve each strategic objective? MacArthur’s proposal offered a different calculation entirely. Instead of trading American lives for Japanese territory, they would trade time for the complete elimination of Japanese combat effectiveness.

The orders Roosevelt signed that afternoon in Quebec would reshape the Pacific War in ways none of the participants fully understood. Operation Cartwheel would prove that 20th century warfare had evolved beyond the simple capture and defense of geographic positions. In an age of aircraft carriers and long-range bombers, controlling the sea and air around an enemy stronghold could be more valuable than controlling the stronghold itself.

100,000 Japanese soldiers at Rabal were about to discover that the strongest fortress in the Pacific could become the most isolated prison on Earth. The first bombs fell on Rabal at dawn on October 12th, 1943. 350 American aircraft launched from Henderson Field on Guadal Canal in the largest air raid the Pacific had yet witnessed.

Their formations stretching across 40 m of sky as they approached the volcanic ridges surrounding Simpson Harbor. General Hoshi Imamura watched from his command bunker as explosions walked across Lacunai airfield. Each detonation sending pillars of smoke and debris 500 ft into the air. The attack lasted 47 minutes and destroyed 36 Japanese aircraft on the ground.

But Immur understood that the bombers themselves were not the real threat. The real threat was what was their presence revealed about American capabilities. Within 72 hours of the Bugganville landings, American CBS began constructing an airfield at Cape Toolkina that would bring Rabal within range of daily bombing missions.

The engineering feat required moving 200,000 cubic yards of coral and volcanic soil while under intermittent Japanese artillery fire. But the construction proceeded with mechanical precision. Each day brought measurable progress. Runway length extended by another 500 ft. Fuel storage tanks multiplied. Ammunition bunkers carved deeper into the coral foundations.

Lieutenant General Imamura’s intelligence officers provided regular updates on American construction activities, and each report confirmed his growing suspicion that MacArthur had no intention of launching a direct assault on Rabal’s defenses. The strategic isolation of Rabal accelerated through November as American forces captured airfield sites throughout the northern Solomons.

Japanese supply convoys attempting to reach Simpson Harbor faced an expanding gauntlet of air attacks from newly operational American bases. The destroyer Suzuki carrying medical supplies and replacement aircraft engines took bomb hits from Liberator bombers operating out of Munda and sank 12 mi south of New Ireland with the loss of 63 crew members.

Two days later, the cargo vessel Kenai Maru, loaded with rice and canned fish intended for Rabol’s garrison, suffered a similar fate when Corsair fighters from Vela Lavella, strafed the ship until her cargo holds flooded with seaater and food supplies. Admiral Janichi Kusaka, commanding the 11th airfleet at Rabul, watched his operational strength decline with each passing week as replacement aircraft failed to arrive and maintenance supplies dwindled.

By December 1943, he could launch fewer than 80 serviceable fighters and bombers, down from more than 300 aircraft just 2 months earlier. The mathematics of attrition were working against Japanese forces with devastating efficiency. American production facilities delivered new aircraft to Pacific airfields faster than Japanese mechanics could repair battle damage with increasingly scarce replacement parts.

The human cost of isolation became apparent in the daily routine of Japanese soldiers stationed at Rabal. Rice rations were reduced to 2/3 normal portions in November, then half rations by January 1944 as supply ships struggled to penetrate the expanding ring of American air bases. Fresh vegetables disappeared entirely from military kitchens, replaced by canned goods salvaged from merchant vessels that had run the blockade months earlier.

Medical supplies grew so scarce that army surgeons began reusing bandages and operating without anesthesia for minor procedures. Yet discipline remained intact and morale while declining had not reached the breaking point that American Hawaii intelligence analysts had predicted. General Imamura recognized the strategic trap MacArthur had constructed around Rabal, but his response revealed both the strength and limitations of Japanese military thinking.

Rather than attempting a breakout that would abandon the fortress his emperor had ordered him to defend, Imamura chose to maximize the defensive value of his isolated position. Engineers reinforced existing bunker systems with coral and steel salvaged from damaged aircraft. Coastal artillery crews practiced nightfiring drills to conserve daylight hours for concealment from American reconnaissance flights.

Most significantly, Imamura began converting Rabul from an offensive stronghold into a defensive citadel designed to absorb American resources for as long as possible. The first major test of Rabal’s defensive capabilities came on February 15th, 1944 when American bombers from newly operational bases in the Admiral T Islands launched coordinated attacks against Japanese shipping in Simpson Harbor.

The raid involved 230 aircraft flying in precise formation. Their bomb loads calculated to maximize damage against vessels mored at the harbor’s concrete warves. Japanese anti-aircraft defenses responded with desperate intensity, filling the sky above the harbor with black puffs of exploding shells, but the sheer volume of attacking aircraft overwhelmed defensive positions.

Seven merchant vessels and two destroyers took direct hits, their burning hulks settling into the harbor mud and reducing Rabal’s cargo handling capacity by 40%. The psychological impact of constant bombing created tensions within Rabul’s garrison that military discipline could barely contain. Soldiers who had volunteered for combat duty found themselves trapped in underground bunkers while American aircraft attacked targets overhead with methodical precision.

The frustration of elite infantry units reduced to passive observers of their own destruction manifested in increased disciplinary problems. Black market trading of scarce supplies and growing resentment toward officers who seem powerless to break the siege. Lieutenant Colonel Yoshimasa Tanaka, commanding the third battalion of the 65th Infantry Regiment, reported to his superiors that morale among his men had declined significantly since Christmas, and that several soldiers had been caught attempting to construct improvised boats capable of reaching New

Ireland. By March 1944, the strangle hold around Rabal had achieved effects that exceeded MacArthur’s original projections. Japanese radio communications revealed desperate requests for medical evacuations that could not be fulfilled, ammunition shortages that limited artillery responses to American bombing raids, and fuel shortages so severe that remaining aircraft were grounded except for the most critical reconnaissance missions.

Intelligence intercepts indicated that Imamura had begun rationing aviation gasoline to preserve enough fuel for a final defensive effort if American ground forces attempted to land on New Britain. The irony of Rabul’s situation became clear to American observers monitoring Japanese radio traffic throughout the spring of 1944.

The fortress that had been designed to project Japanese power across the South Pacific had become a massive consumer of resources it could no longer obtain. 100,000 soldiers, thousands of tons of military equipment, and extensive fortifications that had cost the Japanese Empire 2 years of construction effort were now effectively neutralized without a single American soldier setting foot on New Britain’s beaches.

MacArthur’s strategy of isolation had transformed Japan’s greatest Pacific stronghold into a strategic liability that drained Japanese resources while contributing nothing to their war effort. The siege of Rabal had become a demonstration of how modern warfare could achieve decisive results through logistics and air power rather than traditional ground combat.

But the human cost of this new form of warfare was measured in months of slow starvation rather than minutes of violent battle. The surrender message arrived at MacArthur’s headquarters in Manila on August 6th, 1945, transmitted through neutral Swiss diplomatic channels and bearing the personal seal of General Hatoshi Imamura.

After 22 months of isolation, the commander of Japan’s most formidable Pacific fortress was ready to negotiate terms for the capitulation of his garrison. The document written in formal Japanese military language and translated by intelligence officers who had monitored Rabal’s radio traffic since the siege began contained a single paragraph that revealed the complete success of MacArthur’s strangle hold strategy.

Imamura reported that his forces possessed ammunition for less than 3 days of combat, medical supplies sufficient for basic first aid only, and food reserves calculated to sustain his remaining troops for 2 weeks at starvation rations. The physical transformation of Rabul’s garrison shocked American officers who flew reconnaissance missions over Simpson Harbor during the final weeks of the siege.

Aerial photographs revealed Japanese soldiers who had constructed vegetable gardens in bomb craters, dismantled aircraft engines to forge cooking implements, and converted ammunition bunkers into workshops for repairing uniforms with salvaged parachute silk. The once mighty fortress had become a subsistence community where military priorities were subordinated to the basic requirements of survival.

Intelligence analysts estimated that effective Japanese combat strength at Rabal had declined from 100,000 soldiers to fewer than 30,000 men capable of sustained fighting with the remainder weakened by malnutrition, tropical diseases, and psychological exhaustion. Emperor Hirohito’s surrender announcement on August 15th eliminated any remaining ambiguity about Rabul’s fate.

But General Imamura’s response to Japan’s capitulation revealed the complex psychology of military leadership under impossible circumstances. Rather than immediately ordering his troops to lay down their weapons, Imamura spent 48 hours consulting with subordinate commanders about the mechanics of surrender. His primary concern was ensuring that the capitulation process would preserve the dignity of soldiers who had endured nearly two years of isolation without breaking discipline or abandoning their posts.

The general’s final orders to his garrison emphasized that their surrender represented obedience to the emperor’s will rather than military defeat, a distinction that carried profound meaning for men whose entire identity was built around concepts of honor and duty. The first American representatives to enter Rabol arrived on August 28th aboard a single transport aircraft that landed on Lakunai airfield under a white flag of truce.

Colonel Harold Regelman, serving as MacArthur’s personal representative, later described his initial impression of Japanese defenses that had been built to withstand the most powerful amphibious assault in military history. Concrete bunkers 6 ft thick lined the harbor approaches. Their firing ports designed to create interlocking fields of fire that would have devastated any invasion fleet.

Underground tunnels connected defensive positions across several miles, allowing troops and supplies to move without exposure to aerial attack. Coastal artillery pieces, some salvaged from battleships and Mount Dawn railway cars, commanded every approach to Simpson Harbor with guns capable of sinking cruisers at ranges exceeding 20 m.

The irony of Rabal’s surrender became apparent as American officers tooured installations that had never been tested in actual combat. Japanese engineers had spent two years constructing the most sophisticated fortress complex in the Pacific, complete with underground hospitals, ammunition factories, and communication centers capable of coordinating defensive operations across hundreds of square miles.

Yet, the elaborate defensive preparations had proven irrelevant against MacArthur’s strategy of isolation. The fortress had fallen without a single American soldier firing a shot at its defenses, demonstrating that modern warfare had evolved beyond the traditional siege tactics that had dominated military thinking for centuries.

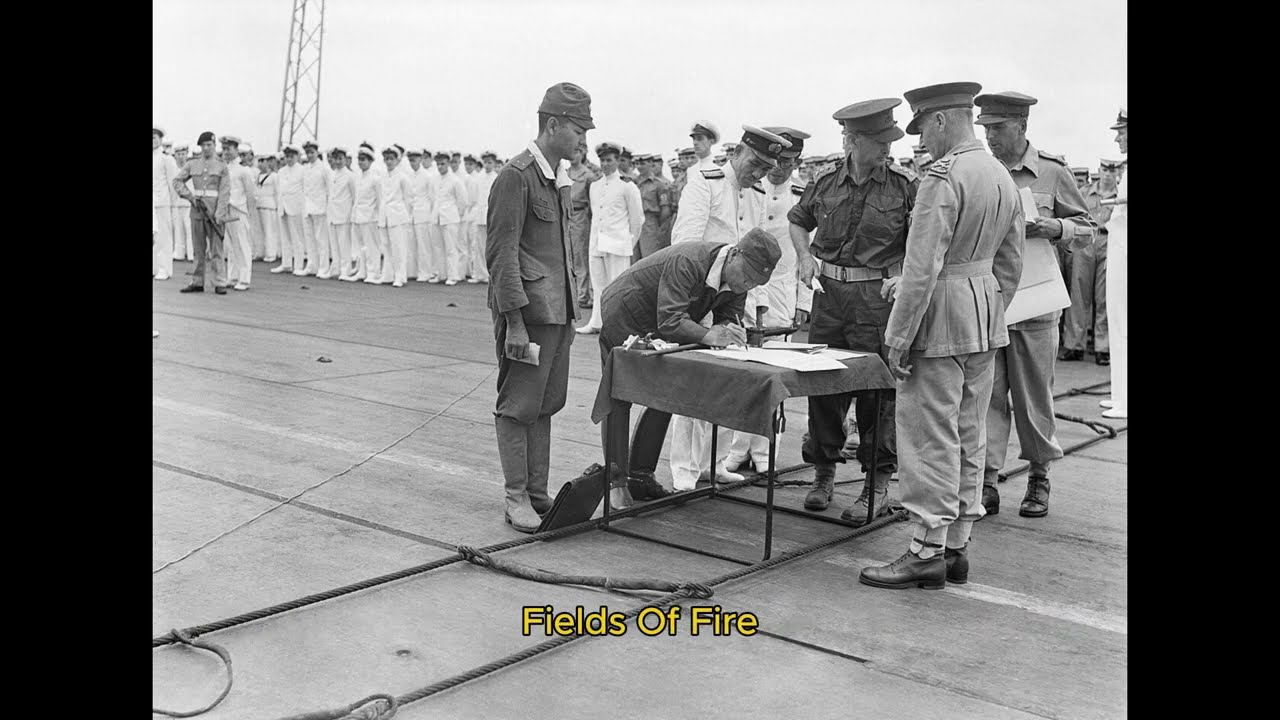

General Imamura’s personal surrender on September 6th, 1945 took place in the same command bunker where he had planned desperate breakout attempts during the darkest months of the siege. The ceremony was brief and conducted with the formal courtesy that characterized Japanese military culture even in defeat.

Imamura presented his sword to Colonel Regalman with a short speech, acknowledging the skill of American strategy while maintaining that his garrison had fulfilled their duty to the emperor by holding Rabol until ordered to surrender. His words revealed both professional respect for MacArthur’s tactics and bitter recognition that his 100,000 soldiers had been rendered irrelevant to Japan’s war effort through strategic isolation rather than military defeat.

The human cost of the siege became clear as American medical teams began evaluating Japanese personnel during the surrender process. Malnutrition had affected nearly every soldier in the garrison with many men weighing 30 to 40 pounds less than their normal body weight. Tropical diseases including malaria, dysentery, and deni fever had reached epidemic proportions due to inadequate medical supplies and deteriorating sanitary conditions.

Psychological casualties were harder to quantify, but clearly evident in the behavior of soldiers who had spent 22 months under constant threat of bombing attacks. they could not prevent or escape. Many Japanese personnel exhibited symptoms that American psychiatrists would later recognize as combat fatigue, a condition that had affected their own forces during prolonged campaigns.

The strategic implications of Rabol’s surrender extended far beyond the immediate tactical situation in the South Pacific. MacArthur’s demonstration that a major enemy stronghold could be neutralized through isolation rather than direct assault influenced American planning for the projected invasion of Japan.

Military analysts concluded that similar stranglehold tactics might be applied to Japanese home islands using air power and naval blockade to reduce enemy resistance before any amphibious landings became necessary. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had rendered such considerations academic, but the lessons learned from Rabul’s siege would influence American military doctrine throughout the Cold War era.

The final chapter of Rabul’s story was written in the months following Japan’s surrender as Australian forces assumed responsibility for repatriating Japanese personnel and dismantling military installations. The process required careful planning to handle nearly 80,000 surviving garrison members who needed medical attention, food, and transportation to Japan.

Many of the Japanese soldiers had not received mail from their families for more than a year, and their emotional reactions to news of Japan’s defeat and their own survival created logistical challenges that extended well into 1946. The fortress that had once projected Japanese power across the Pacific became a massive humanitarian operation as former enemies worked together to process the surrender of troops who had been forgotten by their own government and ignored by history until MacArthur’s strategy transformed them from elite

soldiers into hostages of their emperor’s ambitions. The strategic revolution that began with MacArthur’s decision to bypass Rabul rippled across every theater of the Pacific war during the final 18 months of the conflict. Admiral Chester Nimttz, initially skeptical of the isolation strategy, found himself adapting similar tactics as American forces approached the heavily fortified Japanese positions in the Marshall and Caroline Islands.

The fortress at Trou once considered the Gibralar of the Pacific with its massive naval base and complex of defensive installations suddenly faced the same fate as Rabal when American planners realized that capturing surrounding atols would neutralize the stronghold more efficiently than direct assault. The lessons learned from 22 months of strangling Japan’s South Pacific bastion had fundamentally altered American strategic thinking about modern warfare.

General Curtis Lameé, commanding the 21st Bomber Command from bases in the Mariana Islands, recognized that the Rabal model could be applied on a vastly larger scale against the Japanese home islands themselves. His strategic bombing campaign against Japan’s industrial cities employed the same principles of isolation that had proven so effective against Imamura’s garrison, but expanded to target an entire nation’s capacity to sustain military operations.

Rather than attempting to destroy every factory and military installation through direct attack, LAME’s bombers focused on transportation networks, fuel refineries, and port facilities that connected Japan’s scattered industrial centers. By the spring of 1945, Japan faced the same logistical strangulation that had crippled Rabul, but on a national scale that affected 60 million civilians as well as military forces.

The psychological impact of the Rabul siege extended beyond immediate tactical considerations to influence Japanese strategic planning throughout the Pacific. Intelligence intercepts revealed that Japanese commanders at other isolated garrisons had begun implementing desperate measures to avoid Rabal’s fate, including attempts to construct submarine supply routes, experimental use of long range aircraft for supply missions, and even consideration of breakout attacks designed to reach areas where conventional supply lines remained intact. The fortress mentality that had

dominated Japanese defensive thinking since 1942 was breaking down as commanders realized that static fortifications could become death traps if enemy forces controlled the surrounding sea and airspace. Emperor Hirohito’s private discussions with senior military advisers during the final months of the war revealed the profound impact that Rabal’s isolation had on Japanese leadership’s understanding of their strategic position.

Palace records later recovered by American occupation forces indicated that the emperor had specifically cited the fate of Imamura’s garrison as evidence that Japan could not sustain prolonged defensive warfare against American industrial capacity and logistics expertise. The spectacle of one 100,000 elite soldiers reduced to subsistence farming while American bombers operated overhead with impunity demonstrated that Japan’s traditional emphasis on spiritual strength and warrior discipline could not overcome material disadvantages of such magnitude.

The cost calculations that had initially justified MacArthur’s bypass strategy proved even more favorable than American planners had anticipated when final casualty figures were compiled after Japan surrender. The direct assault on Rabal that MacArthur had avoided would have required an estimated 30,000 American casualties based on experiences at Terawa Saipan and other heavily fortified Japanese positions.

Instead, American losses during the 22-month siege consisted primarily of air crew members shot down during bombing missions, totaling fewer than 800 killed and missing. The strategic value of neutralizing 100,000 Japanese troops while preserving American lives had exceeded every projection made during the Quebec conference deliberations in August [clears throat] 1943.

The long-term implications of the Rabul siege became apparent as American military doctrine evolved during the immediate post-war period. The Joint Chiefs of Staff commissioned detailed studies of the operation’s effectiveness, focusing particularly on the role of air power in maintaining strategic blockades and the psychological effects of prolonged isolation on enemy morale.

These analyses influenced American planning for potential conflicts with the Soviet Union, where similar bypass tactics might be employed against heavily fortified positions in Eastern Europe or remote military installations that could be isolated through conventional air and naval operations.

General MacArthur’s retrospective assessment of the Rabol operation delivered to a joint session of Congress in April 1951 emphasized the fundamental shift in military thinking that the siege had represented. Modern warfare, MacArthur argued, had evolved beyond the simple capture and defense of geographic positions to become a contest of industrial production, logistical efficiency, and strategic patience.

The general credited the success at Rabbal with proving that American forces could achieve decisive strategic results without accepting the massive casualties that had characterized previous conflicts. A lesson that would influence military planning throughout the Cold War era. The human dimension of the Rabal siege was perhaps best captured in the personal diary of Lieutenant Hiroshi Yamamoto, a Japanese artillery officer whose journal was discovered by Australian forces during the surrender process. Yamamoto’s entries spanning

from the first American bombing raids in October 1943 through the final weeks before capitulation documented the gradual transformation of elite soldiers into desperate survivors struggling with malnutrition disease and the psychological strain of prolonged isolation. His final entry, dated August 10th, 1945, expressed both relief that the ordeal was ending and profound sadness that so many of his comrades had died, not in glorious battle, but from preventable diseases and starvation.

The strategic legacy of Rabul’s siege extended far beyond the immediate context of World War II to influence American thinking about limited warfare, asymmetric conflict, and the role of economic pressure in achieving political objectives. The demonstration that a major enemy stronghold could be neutralized through patient application of superior logistics and air power rather than costly direct assault became a cornerstone of American military doctrine during conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf.

MacArthur’s decision to bypass Rabal had proven that in modern warfare, the most decisive victories often came not from heroic charges against enemy fortifications, but from the methodical application of industrial superiority and strategic patience that could transform an enemy’s greatest asset into their most vulnerable liability.

The repatriation ships that departed Rabal between September and December 1945 carried more than 70,000 Japanese survivors back to a homeland they barely recognized after nearly 4 years of total war. Many of these soldiers had been deployed to the South Pacific in early 1942 when Japan controlled territory from the Aleutian Islands to the edge of Australia, and their shock at learning the extent of their empire’s collapse was compounded by the physical and psychological trauma of 22 months under siege.

Lieutenant Colonel Masau Watanabe, formerly commanding officer of the 41st Infantry Regiment, Second Battalion, later wrote that the Japan he encountered upon his return seemed like a different country entirely, with cities reduced to ash, civilians dressed in rags, and a defeated population struggling to comprehend how their divine emperor could have surrendered to foreign powers.

The medical examination reports compiled by Allied doctors during the repatriation process revealed the full extent of what prolonged isolation had inflicted on Rabol’s garrison. Nearly 60% of the surviving Japanese personnel showed signs of severe malnutrition with average weight loss ranging from 25 to 40 lbs per individual.

Tropical diseases had reached epidemic proportions within the isolated fortress with malaria affecting over 80% of personnel in dysentery claiming more lives during the final 6 months of the siege than American bombing raids had caused during the entire 22-month period. Perhaps most significantly, the psychological evaluations conducted by military psychiatrists identified symptoms of what would later be recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder in more than half of the repatriated soldiers, many of whom had developed severe anxiety. Reactions to

aircraft sounds after enduring daily bombing attacks for nearly 2 years. The economic analysis conducted by American occupation authorities in Japan provided stark evidence of how effectively the bypass strategy had neutralized Japanese military resources. The supplies, equipment, and personnel trapped at Rabol represented an investment equivalent to 12 infantry divisions that could have been deployed to defend the Philippines, Ewoima, or Okinawa during the final campaigns of the Pacific War.

Intelligence estimates suggested that if even half of Rabal’s garrison had been available for the defense of Luzon, American casualties during MacArthur’s Philippine campaign might have doubled. The strategic opportunity cost of maintaining 100,000 soldiers in an isolated fortress while American forces advanced toward Japan demonstrated the cascade effect of MacArthur’s decision to bypass rather than assault the South Pacific stronghold.

General Imamura’s war crimes trial in Manila during 1946 provided an unexpected form for examining the moral implications of the siege warfare that had characterized the Rabal operation. Defense attorneys argued that their client had been placed in an impossible position by his own government’s strategic decisions. abandoned without adequate supplies or reinforcements while ordered to maintain a defensive posture that served no meaningful military purpose after American forces had moved beyond the South Pacific theater. The prosecution

countered that Imamura’s treatment of Allied prisoners and forced laborers during the construction of Rabul’s defenses constituted clear violations of international law. But the broader questions raised by the trial touched on the ethics of prolonged siege warfare and the responsibilities of commanders whose forces had been strategically isolated by enemy action.

The intelligence revelations that emerged from captured Japanese documents during the occupation period shed new light on the internal debates that had raged within Tokyo’s military leadership about Rabul’s fate. Senior staff officers had recognized as early as February 1944 that the fortress served no strategic purpose and recommended evacuating the garrison to reinforce more critical defensive positions.

But Emperor Hirohito himself had insisted that Rabol be held as a matter of national honor. The decision to maintain 100,000 soldiers in an isolated position while American forces prepared for the invasion of Japan represented one of the most costly strategic mistakes in Japanese military history. And the captured documents revealed that several senior commanders had privately questioned the emperor’s judgment while publicly maintaining absolute loyalty to his directives.

The technological lessons learned from the Rabol siege influenced American military development programs throughout the early cold war period as defense planners sought to understand how air power and logistics could achieve strategic objectives without the massive casualties associated with traditional ground combat.

The Army Air Forces commissioned detailed studies of bombing effectiveness against isolated targets, leading to improved tactics for interdicting supply lines and maintaining prolonged air campaigns against enemy positions. The Navy’s analysis of blockade operations around Rabal contributed to the development of submarine warfare doctrine that would prove crucial during potential conflicts with the Soviet Union where similar isolation tactics might be employed against remote military installations or island bases.

The human stories that emerged from Rabul’s siege provided American audiences with their first detailed understanding of how modern siege warfare affected both the besieged and the besiegers. Sergeant James Morrison of the 13th Air Force, who had flown bombing missions against Rabol for 18 consecutive months, later described the psychological strain of attacking the same targets repeatedly, while knowing that thousands of enemy soldiers were slowly starving in the ruins below.

The moral ambiguity of warfare that killed through deprivation rather than direct combat troubled many American veterans who had expected more conventional battles against clearly defined military targets. The strategic doctrine that evolved from the Rabbal experience emphasized the importance of controlling maritime and aerial supply lines as the decisive factor in modern warfare.

Military theorists at the war college concluded that future conflicts would be won not by armies that could capture and hold territory, but by forces capable of severing enemy logistics networks while maintaining their own supply chains across vast distances. This analysis proved remarkably preient as American forces encountered similar challenges during the Korean conflict where control of supply routes from Chinese bases proved more significant than tactical victories on the ground.

The final assessment of MacArthur’s bypass strategy came not from military historians, but from Japanese veterans who had survived the siege and could evaluate its effectiveness from the perspective of those who had experienced its consequences directly. Colonel Teeshi my formerly Imamura’s chief of operations wrote in his postwar memoir that the American decision to isolate rather than assault Rabal had demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of modern warfare the Japanese commanders had failed to appreciate. The realization that their

most powerful fortress could become their greatest weakness through strategic isolation rather than tactical defeat represented a fundamental shift in military thinking that would influence defensive planning for decades to come. The siege of Rabal had proven that in the age of air power and industrial warfare, the strongest fortifications were only as secure as the supply lines that sustained them.