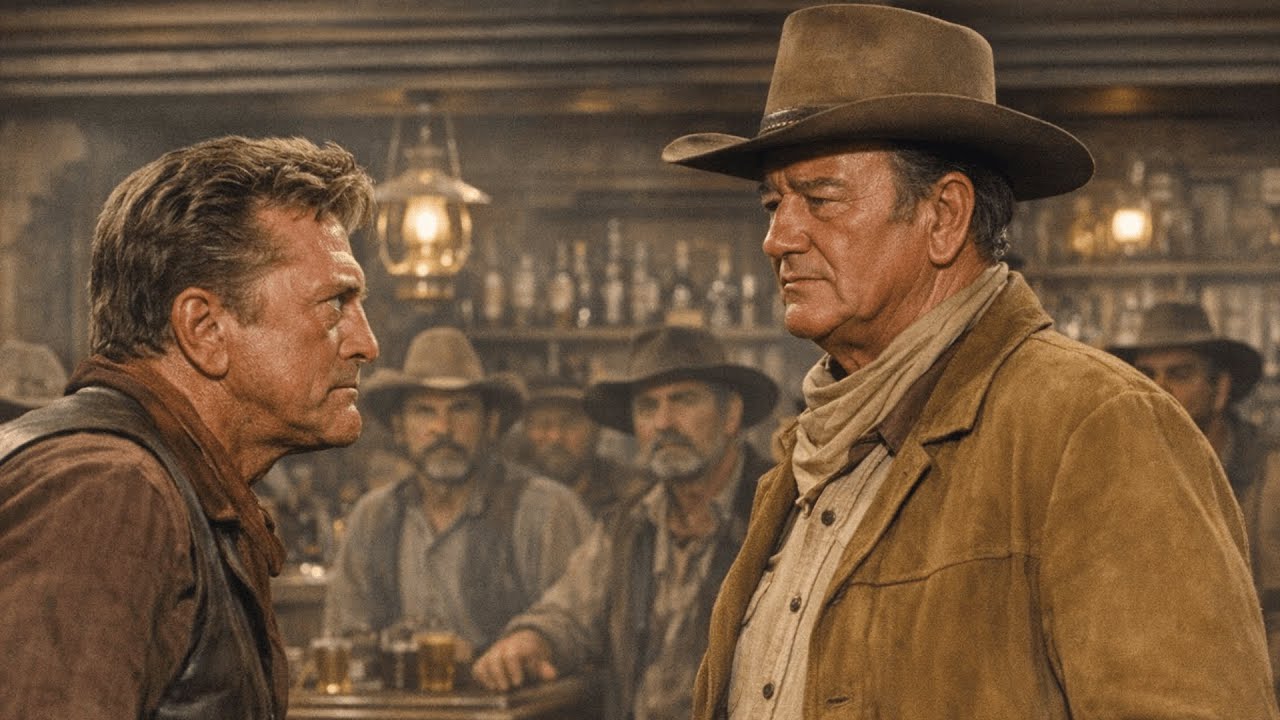

The glass exploded against the bar, missing Kirk Douglas’s head by inches. John Wayne stood frozen 10 ft away, arm still extended from the throw, his face twisted with a kind of anger no one on that set had ever seen before. You want to tell me how to play this scene again. Wayne’s voice cut through the saloon like a gunshot.

Go ahead, Kirk. Say it one more time. Douglas didn’t move, didn’t blink. He just smiled, calm, defiant. I wasn’t telling you how to play it, Duke. He said, I was telling you how I am. The cameras stopped. The crew froze because in that moment, the War Wagon wasn’t a movie anymore. It was about to become a real fight. Here is that story.

The War Wagon was supposed to be a straightforward western. John Wayne would play Todd Jackson, a man framed and imprisoned by a corrupt mining baron who returns for revenge. Kirk Douglas would play Lomax, a gunfighter hired to kill Jackson, who instead becomes his partner in a scheme to rob the Baron’s gold shipment.

On paper, it was a perfect pairing. Two legendary stars, both at the height of their powers, combining forces for what the studio expected to be a guaranteed box office success. What the studio didn’t anticipate was that Wayne and Douglas had spent years developing a mutual antagonism that went far beyond professional competition.

Wayne represented old Hollywood, the studio system, conservative values, a particular vision of American masculinity that had dominated cinema for three decades. He believed in hierarchy, in respecting the chain of command, in stars who accepted their roles within an established order. Douglas represented something different.

He had helped break the studio system by hiring blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo for Spartacus. He produced his own films, controlled his own destiny, challenged conventions that Wayne considered sacred. He was a Democrat in an industry Wayne believed should support conservative causes. He was everything Wayne distrusted about the direction Hollywood was heading.

They had managed to avoid working together for years. Now circumstances had forced them into the same film, the same scenes, the same cramped sound stage in Mexico, where temperatures soared and tempers ran even hotter. The explosion was inevitable. The only question was when it would come. Problems emerged during the first week of shooting.

Small things at first, disagreements about blocking, debates about line readings, tension in scenes that should have been routine. Wayne had a particular way of working. He arrived on set knowing exactly how he would play every moment. His preparation was meticulous but invisible. He made everything look natural, effortless, as if he were simply being himself rather than acting.

He expected his co-stars to adapt to his rhythms to find their performances around his established presence. Douglas worked differently. He approached each scene as a negotiation, a collaboration between actors who should be finding the moments together. He didn’t want to simply react to Wayne.

He wanted to engage with him, challenge him, create friction that would make the scenes more dynamic. The clash was immediate and fundamental. During a confrontation scene in the second week, Douglas delivered his lines with an intensity that surprised Wayne. Instead of playing Lomax as subordinate to Jackson, which Wayne expected, Douglas played him as an equal, as dangerous and capable as the hero himself.

Wayne pulled the director aside after the take. He’s stepping on my scenes, playing it too big. He needs to pull back. The director, Bert Kennedy, faced an impossible situation. Telling Kirk Douglas to diminish his performance was like telling a hurricane to diminish its winds. Douglas had been a star as long as Wayne.

He had produced his own films. He answered to no one’s vision but his own. Kennedy tried diplomacy. It failed immediately. Duke thinks I’m playing it too big. Douglas responded when approached. Duke plays every scene like he’s the only person in the frame. Maybe if he noticed his co-stars existed, we could find a different rhythm.

The message got back to Wayne. The temperature on set dropped 20°. The saloon scene was scheduled for a Wednesday afternoon, a key sequence where Jackson and Lomax negotiate their partnership, each man sizing up the other, neither willing to show weakness. The set was elaborate. A full western saloon reconstructed on the sound stage with authentic period details.

The crew had spent two days preparing lighting and camera positions. Everything was ready for what should have been a straightforward dialogue scene. Wayne arrived first. As was his custom, he walked through the blocking with stand-ins, familiarizing himself with the space, establishing his territory. When Douglas arrived 30 minutes later, Wayne was already seated at the bar, occupying the position of power in the scene. Douglas noticed immediately.

The blocking they had rehearsed the previous day had both men standing. Wayne had unilaterally changed it. “I thought we were doing this on our feet,” Douglas said to the director. Kennedy shifted uncomfortably. Duke felt the scene played better if Jackson was seated when Lomax enters. Shows confidence.

He’s not threatened. Douglas looked at Wayne, who was examining his fingernails with elaborate disinterest. So now Duke’s directing. Wayne finally looked up. I’m protecting the scene, Kirk. Something you might understand if you’d been doing this as long as I have. I’ve been doing this exactly as long as you have.

Not the same kind of doing. The crew sensed what was building. Gripps found reasons to check equipment at the far end of the sound stage. The script supervisor suddenly needed to consult her notes in another room. “What’s that supposed to mean?” Douglas asked, his voice dropping to a register that anyone who knew him recognized as dangerous.

Wayne stood slowly, unfolding his considerable height, using his physical presence the way he’d used it in a hundred films. “It means I make westerns, real westerns. You make spectacles with gladiators and ancient Romans. This is my territory, Kirk. You’re a guest here. Douglas laughed. Not a diplomatic laugh or a consiliatory one.

A genuine dismissive laugh that seemed to suggest Wayne had said something absurd. Your territory, Duke. The Western doesn’t belong to you. It’s a genre, a set of conventions. Other people get to play in it, too. Other people don’t come onto my set and tell me how to play a scene. I didn’t tell you anything.

I told Kennedy how I was going to play it. You’re the one who decided that was a threat. Wayne stepped closer. They were now separated by only a few feet. Close enough that the tension between them felt physical. You’ve been undermining me since we started shooting. Playing scenes bigger than they need to be. Mugging for the camera.

Turning Lomax into something he’s not supposed to be. And what is Lomax supposed to be? A sidekick? Comic relief? someone who makes John Wayne look taller by comparison. He’s supposed to be a supporting character in a John Wayne western. Douglas shook his head slowly. There’s your problem, Duke. You think everything with your name on it belongs to you alone, but I didn’t sign up for a supporting role.

I signed up for a partnership. Two stars, equal billing, equal screen time. If you can’t handle that, maybe you should make movies alone. The words landed like physical blows. Wayne’s face flushed, his hands clenched. You think you’re my equal? I know I am. What happened next would be described differently by everyone who witnessed it.

Some remembered Wayne throwing the first glass. Others claimed Douglas made a provocative gesture that triggered the response. The details varied, but the outcome was consistent. Wayne grabbed a whiskey glass from the bar, a prop filled with colored water, and hurled it at the space beside Douglas’s head. The glass shattered against a wooden post, sending fragments and liquid across the set. Douglas didn’t retreat.

He grabbed his own glass and threw it back, missing Wayne deliberately, shattering it against the bar. “That’s how you want to do this?” Douglas said, “Fine, let’s do it.” They didn’t come to blows. Years later, both men would acknowledge that they had come close, closer than either had ever come with any co-star, but something stopped them at the threshold of actual violence.

Maybe it was professionalism. Maybe it was awareness that fighting would shut down production and cost everyone money. Maybe it was something else. A mutual recognition that they were too evenly matched. That actual combat might not have a clear winner. Instead, they stood frozen in that saloon set, breathing hard, surrounded by broken glass and stunned crew members, neither willing to back down and neither willing to escalate further.

Kennedy finally found his voice. Gentlemen, I think we need a break for the day. Wayne turned and walked off the set without another word. Douglas watched him go, then calmly brushed glass fragments from his shoulder. Same time tomorrow? Douglas asked. No one in particular. Nobody answered. Production shut down for 3 days.

The studio panicked. Insurance representatives flew to Mexico to assess whether the film could be completed. Lawyers reviewed contracts, calculating damages if one star refused to continue working with the other. The two men retreated to opposite ends of the production compound, avoiding each other entirely. Their entouragees formed separate camps, communicating only through intermediaries.

The atmosphere felt less like a movie set than a diplomatic crisis between hostile nations. Kennedy spent those three days in shuttle diplomacy, moving between the camps, trying to find a path forward. He quickly discovered that the conflict went far deeper than the saloon scene. It touched on everything the two men represented and everything they believed about filmm. Wayne’s position was clear.

This was his kind of film, his territory, and Douglas needed to respect the established order. Wayne had been making successful westerns for 40 years. His name drove box office. His approach worked. Douglas was a talented actor, but he was a guest in a house Wayne had built. Douglas’s position was equally firm.

He had signed for equal billing and equal treatment. He wasn’t interested in diminishing his performance to make Wayne more comfortable. The film would be better if both stars brought their full intensity to the screen. Wayne’s ego was the only obstacle. Kennedy reported back to the studio. Both men were professionals who wanted to finish the film, but neither would apologize.

Neither would change their approach. Some kind of accommodation was needed that didn’t require either man to surrender. The solution came from an unexpected source. Bert Lancaster, Douglas’s frequent collaborator and occasional rival, called from Los Angeles with advice. Kirk Lancaster said, “Duke’s never going to treat you as an equal. It’s not personal.

It’s how he’s built. He needs to be the star.” But here’s the thing. Audiences don’t care about hierarchy. They care about what’s on screen. Give Duke his moments, take yours. You’ll both look good and the picture will work. Douglas resisted at first. The principle mattered to him. He had spent his career fighting for creative control, for the right to shape his own performances, surrendering that even strategically felt like betrayal of everything he’d worked for.

But Lancaster pressed the practical argument. The film was half finished. Walking away would mean legal battles, financial losses, and a public relations disaster. The professional choice was completion. Douglas agreed to try. Meanwhile, Wayne received similar counsel from his own circle. The studio made clear that the film needed to be finished, that insurance wouldn’t cover abandonment due to personality conflict, that both stars would suffer financially and professionally if the war wagon collapsed. Wayne also agreed to try. 4

days after the saloon confrontation, production resumed. The atmosphere remained tense, but both men arrived on time, prepared, professional. Kennedy had restructured the shooting schedule to minimize scenes where Wayne and Douglas appeared together. When they did share the frame, he worked out blocking in advance with both camps, ensuring no surprises.

The result was strange but functional. Two stars orbiting the same film while barely acknowledging each other’s existence. dialogue delivered with technical precision but minimal emotional connection. Scenes that played adequately but lacked the chemistry the pairing had promised. Everyone knew it wasn’t ideal.

But it was getting the film made. Then something shifted. 3 weeks after the confrontation, Kennedy scheduled a critical sequence, the moment when Jackson and Lomax must work together to overcome impossible odds. When their partnership transforms from convenience to genuine alliance. The scene required something neither man had been willing to provide.

Actual collaboration. Playing adjacent to each other wasn’t enough. The moment demanded connection. Kennedy pulled both men aside separately, making the same case to each. This scene sells the movie. If it doesn’t work, nothing we’ve shot matters. I need you to actually act with each other, not at each other.

With Wayne arrived on set that day with something different in his demeanor. He was quieter than usual, more watchful. He ran through the blocking without complaint, accepting positions that gave Douglas equal prominence in the frame. Douglas noticed the change. He adjusted his own approach, dialing back the intensity that had triggered Wayne’s earlier objections, finding a rhythm that complimented rather than competed.

The cameras rolled. What emerged was remarkable. The tension between the two men, real tension, accumulated over weeks of conflict translated into something electric on screen. Jackson and Lomax clearly didn’t trust each other, clearly were uncomfortable working together, and yet circumstance was forcing them into partnership.

It was exactly what the scene required. Kennedy called cut after the first take. That’s it. That’s what we needed. Wayne and Douglas looked at each other. Something passed between them. Not friendship, not respect exactly, but acknowledgement. Recognition that they had created something together that neither could have created alone.

The remainder of the production proceeded without major incident. The relationship between Wayne and Douglas never warmed into genuine affection, but it evolved into functional professionalism. They had reached an understanding. That understanding was transactional rather than personal.

Both men recognized that their conflict had been hurting the film, that audiences would judge the final product regardless of what happened behind the scenes. They chose to serve the work. It wasn’t reconciliation. Years later, in separate interviews, both would speak carefully about the experience, acknowledging the others talent while stopping well short of enthusiasm.

The War Wagon would be remembered as a good western, a solid professional effort, but not as the beginning of a legendary partnership. Some collaborations are like that. Two brilliant people who simply don’t fit together, whose energies clash rather than combine. the awareness that you can work with someone without liking them, that professionalism can substitute for personal chemistry when necessary.

The War Wagon opened in May 1967 to strong reviews and solid box office. Critics praised the chemistry between Wayne and Douglas, a chemistry that the audience perceived as genuine when it was actually tension transformed by the alchemy of filmm. The premiere brought both men to the same stage for the first time since production ended.

They posed for photographs, answered questions from journalists, presented a unified front that concealed everything that had happened in Mexico. A reporter asked about working together, whether they might collaborate again. Wayne answered first, “Kirk’s a fine actor, professional all the way. We had different approaches, but that’s what makes pictures interesting.

” Douglas smiled tightly. “Duke’s an institution. Working with him was an education. Neither answer was a lie. Neither was the full truth. Both men had learned something from the experience about themselves, about each other, about the limits of what collaboration could achieve when fundamental compatibility was absent.

John Wayne and Kirk Douglas never worked together again. The War Wagon remained their only collaboration, a film born from conflict that somehow transcended its troubled production. Their careers continued on separate tracks. Wayne made more westerns, more war films, cementing his status as the definitive conservative icon of American cinema until his death in 1979.

Douglas continued producing, acting, pushing boundaries, outliving his rival by more than four decades. When asked about each other in later years, both men maintained diplomatic distance. Wayne acknowledged Douglas’s talent while questioning his choices. Douglas acknowledged Wayne’s impact while questioning his politics.

The saloon confrontation became legend, a story told and retold in industry circles, growing more dramatic with each retelling. What actually happened that day in Mexico remains known only to those who witnessed it. The glass throwing, the near violence, the three days of shutdown, the grudging return to professionalism.

The moment when conflict transformed into something audiences could feel. The clash between Kirk Douglas and John Wayne wasn’t really about blocking or line readings or who stood where in a scene. It was about two incompatible visions of what a movie star could be. Wayne believed in serving the system that had made him.

He played his part within established hierarchies, supported the studios that supported him, maintained traditions that gave order to a chaotic industry. His westerns reinforced values he genuinely held. His screen presence reflected an authentic self-image. Douglas believed in challenging every system he encountered.

He had broken the blacklist, produced his own films, insisted on creative control when studios wanted compliant employees. His performances were assertions of individual will against collective expectation. His career was a series of battles won through persistence and talent. Put those two men in the same saloon under pressure competing for the same frame.

An explosion was inevitable. What made the war wagon work was that the explosion didn’t destroy the film, it became the film. The tension between Jackson and Lomax. The uneasy partnership between men who didn’t trust each other. The sense that violence could erupt at any moment. All of it was real.

Transferred from soundstage to screen through the mysterious process by which life becomes art. The audience felt something genuine because something genuine was happening. That’s the truth about the making of the war wagon. Two legends collided. neither surrendered, and the film they made together improbably, impossibly was better for the battle.

If this story showed you what happens when unstoppable forces meet immovable objects, subscribe and share it with someone who appreciates the stories behind the stories. Drop a comment. Do you think the conflict made the film better, or could it have been even greater if they’d actually gotten along?