A 4-Year-Old Boy Was Taken By A Bigfoot, But How The Creature Treated Him Will Shock You!

THE BIG MAN ON MILLER’S RIDGE

Chapter 1: The Miracle Everyone Misnamed

My name is Elias. In this town, most folks see a retired mechanic with grease permanently etched into his hands, a man who keeps to himself and doesn’t linger at the diner. But the older people—the ones who were here in the autumn of ’88—look at me with a different expression. It’s pity, mixed with a kind of reverence. They remember me as the father whose four-year-old son vanished into the Great Smoky Mountains for three freezing nights and somehow came back alive. They call it a miracle. They say God must have held my boy like a blanket when the temperature dropped below zero.

.

.

.

They are wrong.

For thirty years I let them keep the lie because the truth was too sharp to hold. I let the sheriff write “exposure and luck” on the report, let the church tell its story of divine intervention, let the town congratulate itself for praying hard enough. I played the role because I didn’t know what else to do with the knowledge that my son wasn’t saved by heaven. He was saved by something that lives in the woods and doesn’t belong to our rules.

Toby didn’t just get lost. He was taken—plucked from our yard while I was inside answering a phone call that didn’t matter. For seventy-two hours, search dogs, helicopters, and volunteers combed every inch of that ridge. They found nothing. No trail. No scent. No scrap of denim. It was as if the mountain swallowed him whole. I’d already begun building his funeral inside my head, piece by piece, because grief does that—it rehearses the worst until the worst feels inevitable.

Then, on the fourth morning, Toby walked out of the tree line and into the command center like a child returning from a neighbor’s house. He wasn’t shivering. He wasn’t starving. He was dry. He was fed. And his little denim jacket carried a smell so intense it made the tracking dogs whine and flatten to the ground: wild sage, wet fur, and a musk that didn’t belong to any bear or deer or human being.

When I hugged him and searched him for broken bones, he looked up at me with eyes that seemed too old for a toddler. He pointed back at the darkest part of the forest and said, clear as day, “The big man fixed me.”

Chapter 2: Three Minutes and Forty-Five Seconds

October 14th, 1988 is etched into me deeper than my own birthday. It was one of those perfect Appalachian autumn days—the sky a hard, piercing blue, the air smelling like wood smoke and drying tobacco. We lived at the very end of Miller’s Ridge, where the gravel road dead-ended into the boundary line of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Behind our backyard there were no neighbors, no roads, no second chances—just a rusted wire fence and a million acres of dense, ancient forest.

Toby was four and fearless in the way only children can be, convinced the world was safe because his imagination said so. He had a little red Tonka truck he treated like sacred equipment. I was in the garage tinkering with the carburetor on my old Ford, wiping my hands on a rag, watching him through the side door. He was near the edge of the yard, pushing that truck through a pile of leaves and making engine noises. I smiled and shouted the usual warning—stay away from the tree line—like words alone could build a wall.

Then the phone rang inside.

A landline, mounted on the kitchen wall. I almost ignored it. I wish I had. But I was waiting on an auto parts quote, so I jogged in with grease still on my knuckles and picked up. The call lasted three minutes and forty-five seconds. I know because the police later subpoenaed the phone records. Less than four minutes. That was the gap the mountain used.

While I was on the phone, something changed in the house, subtle at first—like a pressure shift before a storm. The crickets stopped. The distant crows went quiet. The wind in the oaks cut off mid-breath. It wasn’t gradual. It was a violent, surgical silence, like nature had been ordered to freeze. Years later I heard someone call it the Oz effect—everything holding its breath because a predator has entered the room.

I hung up with a cold knot in my stomach and stepped onto the porch. “Toby?” I called, expecting the vroom-vroom and giggle.

Nothing.

The swing set was empty. The sandbox undisturbed. The leaf pile scattered—and in the dirt, sitting upright like a witness, was the red Tonka truck. The wheels were still spinning slowly. Spinning meant he had just let go.

I ran to the fence. A section had been pushed down—not cut, not climbed, but forced. The heavy steel post was bent outward at an angle like something with the weight of a tractor had leaned on it without effort. I scrambled over the wire and crashed into the rhododendron thicket, into mud still soft from rain two days earlier. I expected to see small sneaker prints. I expected a trail of panic.

There were no child prints at all.

Instead, there was one massive depression in the moss—eighteen inches long, wide and flat, toes pressed deep into the soil for traction. Barefoot. Not a boot. Not a bear. Something bipedal that didn’t need shoes and didn’t leave mistakes. In that moment, the terror wasn’t only that my son was gone. It was how quickly it happened, how cleanly the woods erased him. I stood there screaming his name until my throat tore, staring at that monstrous footprint filling with muddy water, and I knew I wasn’t searching for a wandering child.

I was chasing a ghost.

Chapter 3: The Evidence I Destroyed

Panic does strange things to a man’s mind. It makes time stutter. It makes you smarter and dumber at the same time. I ran back to the house and called 911, and when the operator answered, I didn’t say “monster” or “Bigfoot.” A colder instinct took control. I said only what would get the fastest response: “My son is missing. He’s four. He was in the yard five minutes ago.”

But before the sheriff arrived, I went back to the tree line, back to that footprint. It was too distinct—biology stamped into mud like a confession. I knew Sheriff Brody. He was practical, no-nonsense, the kind of man who didn’t waste breath on legends. If I dragged him out there and pointed at that track, he wouldn’t see a clue. He’d see a grieving father losing his grip. Worse, he might suspect I’d done something to my own son and invented a story to cover it.

So I made a decision that has weighed on my soul ever since. I stepped into the mud and put my own work boot over the huge print. I stomped. Twisted. Ground the evidence into a meaningless slurry of leaves and muck until the shape disappeared. It felt like betrayal, like I was protecting the kidnapper. But I was gambling on manpower. I needed dogs, radios, volunteers—an army of eyes. And to get that, I had to make this look like a normal disappearance.

When the cruisers arrived, blue lights painting my house in frantic pulses, I played my part. I pointed at the bent fence and lied. “He must’ve climbed over. He’s strong for his age.” Sheriff Brody bought it. Within an hour, the machinery of a rescue operation came alive—flashlights, maps, men in orange vests, names being shouted into radios.

And then the dogs arrived, and my lie met the truth it couldn’t erase.

The lead hound, Duke, sniffed Toby’s Tonka truck, wagged his tail, and pulled toward the fence. But the moment he crossed the boundary line, he stopped dead as if he’d hit an invisible wall. His tail tucked. A high terrified whine escaped his throat. He lay down in the mud and refused to move. The handler yanked the leash, confused. “He’s never done this,” he kept saying, like repetition could make it less real.

I watched from the porch and felt my stomach go cold. Duke could smell what I’d tried to grind away. Whatever had stepped into my yard, Duke knew it was higher on the food chain than he’d ever been asked to track. And my choice to stay silent suddenly sounded like a scream inside my skull.

That night, while volunteers marched into the dark, I understood I wasn’t just lying to people. I was fighting the mountain’s own rules—and the mountain was winning.

Chapter 4: The Knock on Wood

By the second day, the organized search grid began to feel like theater. Men walked the ridges, called Toby’s name, swept flashlights over laurel thickets like light could force the truth to appear. The helicopters clattered above the canopy, and the dogs kept refusing certain pockets of forest as if something there smelled like death.

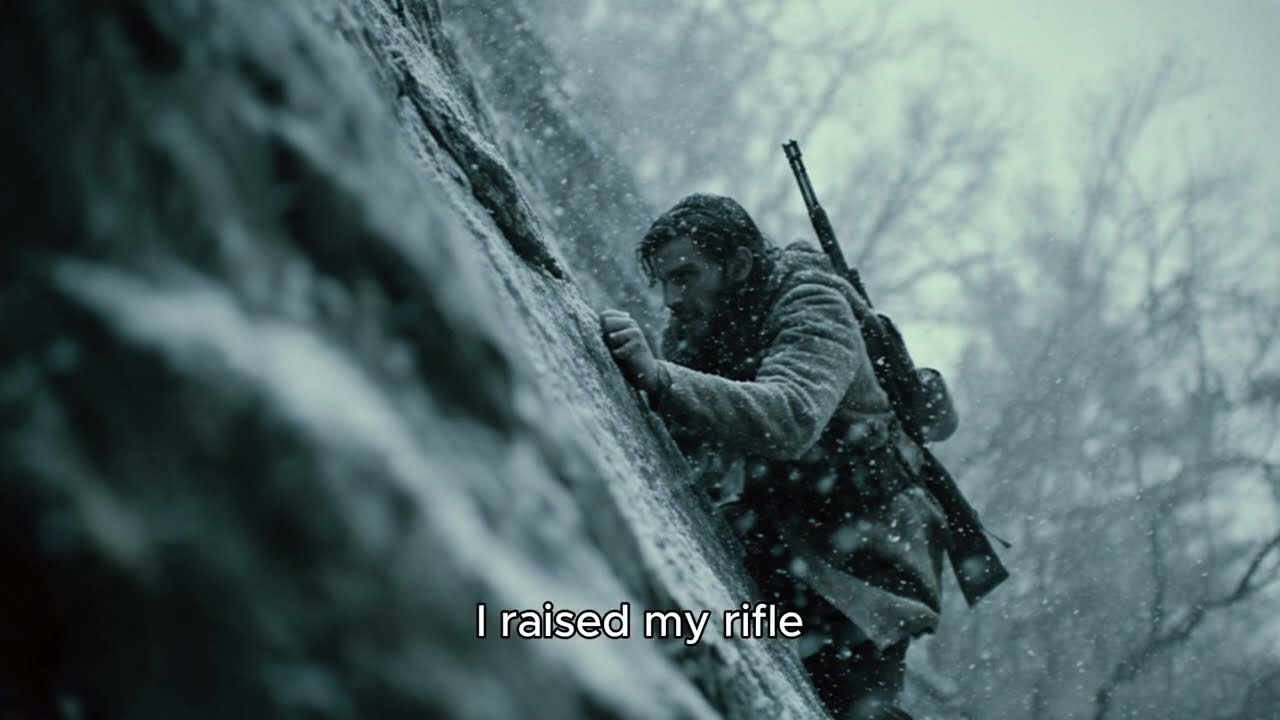

I couldn’t stand it. I left the search line and went alone, higher, deeper, moving on a father’s instinct that wasn’t logic so much as desperation. I carried my rifle because I was angry enough to believe violence could solve grief. The cold sank into my bones; my canteen slushed. My hands cracked and bled. Sleep deprivation turned the woods into a cruel magician. Three times I heard Toby’s voice—clear, thin, calling “Daddy”—and each time I scrambled toward it and found only mist and empty trees, my mind punishing me for hope.

Late on the second day the air changed. The birds didn’t sing. The trees grew older, twisted. And I smelled it—wild sage, wet fur, that heavy musky presence I would later recognize in Toby’s jacket. The smell wasn’t faint. It was fresh, like a warning smeared into the wind.

Near an iced creek bed I found something that stopped me colder than any footprint. On a flat rock in the stream lay three trout—headless, gutted, not eaten—arranged in a triangle with bizarre precision. Bears don’t do that. People do that. Minds do that. I stood there in freezing water, staring at those fish and feeling the terrifying shift from “predator” to “intelligence.” It wasn’t just hiding Toby. It was communicating. Marking. Leaving signs.

That night, the temperature dropped to a hard, brutal freeze. I didn’t make a fire. I was afraid smoke would lure whatever I was following deeper into hiding. I huddled under a rock overhang, wrapped in a foil blanket that felt like paper against the cold, and my mind began to slip. I saw the backyard again and again, the fence bending, the giant hand reaching down. I tried to scream and no sound came.

Then, in the blackness, I heard it: thump… thump… thump. Not wind. Not rockfall. The hollow, deliberate sound of wood knocking—like one tree striking another, slow and methodical, a signal that carried through the mountain as if the forest itself had a heartbeat.

I forced my frozen body upright and began to climb toward the sound, using the rifle like a crutch. I wasn’t alive because of warmth. I was alive because love and hate had twisted into one cord and pulled me forward. I didn’t know it then, but that knocking wasn’t leading me to a corpse.

It was leading me to my son.

Chapter 5: The Nest Without Fire

Just before dawn, the knocking stopped. Silence returned—but different now, intimate, as if I’d stepped into the center of something private. The sage smell was overpowering, thick and resinous, mixed with damp cave-earth. I crawled through one last laurel thicket and found a hidden amphitheater of stone: three massive granite slabs leaning together, a fortress invisible from above.

I raised my rifle, bracing for the worst. I expected a massacre. I expected to see what grief had been rehearsing. Instead, I saw warmth where there should have been none. No fire, no smoke—yet the space under the rock felt insulated, lined with dry pine needles and woven branches like a nest built by hands that understood winter.

And there, sitting cross-legged under the overhang, was the creature.

Even seated it was colossal, a mountain of dark fur that swallowed the dim light. But it wasn’t posturing. It wasn’t roaring. It was cradling something—something small and human, curled against its chest, almost lost in that thick coat.

Toby.

My finger tightened on the trigger out of pure reflex. Then I saw Toby’s face. Peaceful. Asleep. Not struggling. Not crying. The creature’s hand—leathery, huge, nails thick and dark—moved slowly over his back with a gentleness that didn’t fit its size. It pulled dry moss closer around Toby’s shoulders, tucking him in like a parent. It dipped its head and pressed its face to the top of my son’s hair, inhaling, a low rumbling purr vibrating through the rock floor.

Outside, it was eighteen degrees. Inside that stone nest, with the creature’s body heat acting like a living furnace, Toby was warm.

The thought hit me like a blow: if I had found him earlier, if I had dragged him out into the open without shelter, without fire, he might have died anyway. The thing I’d climbed the mountain to kill had done what I could not—kept a four-year-old alive through three nights of freezing wind.

As dawn light crept in, Toby stirred and looked up at the creature like he recognized it. “Thirsty,” he whispered. The creature grunted softly, reached behind a rock, and produced a makeshift cup—gourd or shell—filled with water. It held it to Toby’s lips with careful control. Then it offered nuts and dried berries. Toby patted its arm like it was the most natural thing in the world. “Thank you, big man,” he said, calm as a child thanking a neighbor.

I lowered my rifle an inch, trembling, my worldview cracking under the weight of what I was seeing. The sage smell wasn’t just musk. It was deliberate. The creature had rubbed Toby with crushed sage oils—repellent, medicine, scent-masking—knowledge older than my town, older than my fear.

Then it froze. Its head turned toward the thicket where I hid. It didn’t see me, not yet. It smelled my gun oil. It smelled the human threat I had carried up the ridge.

The miracle was over. The confrontation had arrived.

Chapter 6: The Iron and the Judgment

I stepped into the pale morning light because hiding no longer made sense. My rifle came up on instinct, and the creature rose with a smooth, terrifying grace. One moment it had been a guardian wrapped in fur; the next it was a wall between me and my son, all tension and judgment. It didn’t roar. It released a low-frequency chuff that I felt in my teeth—a warning with no wasted energy.

“Toby!” I shouted, voice thin. Toby peeked around the creature’s leg. “Daddy!” he cried, taking one step toward me.

The creature’s hand snapped down—not striking Toby, but slamming into the earth in front of him, a physical barrier. It wasn’t harming him. It was stopping him. It looked at my rifle the way a man looks at a snake in his child’s bed, and in its eyes was the devastating intelligence of something that understood exactly what a gun does. In that moment, I wasn’t the rescuer. I was the predator bringing iron into a nursery.

“Let him go,” I whispered, my finger trembling near the trigger. The creature didn’t move. It was waiting—for me to prove I wasn’t going to turn this into blood.

It took me a long second to understand the truth: the reunion wasn’t happening because of the creature. It wasn’t holding Toby hostage. It was holding Toby safe from the only immediate danger in that stone chamber—me.

So I made the hardest motion of my life. I clicked the safety on. Lowered the rifle. Then I knelt and placed it on the ground with slow, exaggerated care. I stood and backed away with my hands raised, palms open. “I’m sorry,” I said, and I wasn’t only speaking to Toby. I was speaking to the big man.

The creature sniffed the air again. The tension in its shoulders loosened by a fraction. It looked down at Toby and nudged him gently, like a permission.

Toby ran across the rock and slammed into my legs. I dropped to my knees, wrapped him up, buried my face in his sage-scented jacket, and sobbed until my lungs hurt. “He fixed me,” Toby whispered into my ear. “He kept the cold away.”

Behind us, the creature stood silhouetted in the rising sun like a sentinel, satisfied, as if a task had been completed: keep the small one safe until the big one put down the iron.

Then the helicopter noise arrived, chopping the air apart. The creature’s head tilted toward the sound with irritation. It pointed at the rifle, then toward the cliff path down. An order. Leave. Now.

We left.

As we descended, I heard a single massive crack—wood splintering. The creature snapped a sapling in half and threw the top down the slope behind us. Not an attack. A period at the end of a sentence.

Do not come back.

Chapter 7: Rent and Silence

The descent back to men was noise and flashing lights. The moment we stepped out of the tree line, people surged. Radios barked. A paramedic tried to take Toby from my arms, and I held him too tight because I couldn’t bear to let go of the proof that he was alive. Sheriff Brody demanded answers. “Where was he?” he asked, exhausted and suspicious. “We combed that ridge three times.”

I lied because truth would have turned the mountain into a battlefield. “Under a rock ledge,” I said, flat and hollow. “Just missed him.” The sheriff nodded, accepting the impossible because the alternative was unthinkable.

At the hospital, Dr. Evans examined Toby for an hour and then stared at me the way men stare at a door that shouldn’t exist. “He doesn’t have frostbite,” he said quietly. “No hypothermia. Not even dehydration.” He sniffed Toby’s hair, brow furrowing. “He smells like wild sage and… something else. It’s like his body heat was maintained by an external source. A very warm source.”

The town held a church service. They praised God. I sat in the back pew and felt like a fraud. I wanted to stand up and say it wasn’t heaven. It was a giant in the woods with sage on its hands and mercy in its instincts. But I stayed silent because silence was the only payment that kept the peace.

Toby changed after that. He didn’t speak about the big man to anyone but me. Yet the wild clung to him. He stopped fearing the dark. He sat on the porch and listened as if the night carried messages. He began arranging rocks in triangles and circles. And one evening, a month later, I found him by the repaired fence pushing a peanut butter sandwich through the wire onto a stump beyond.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

He didn’t turn. “Paying rent,” he said. “He likes the crunchy kind.”

On the other side of the fence, in the mud, there was a faint large flat impression—evidence of a watcher checking its investment. The big man hadn’t simply returned my son. He had marked us as part of his world, tolerated tenants on his boundary.

I sold my guns. I stopped hunting. I bought the adjacent acreage to keep developers away. I posted no-trespassing signs every fifty feet and became the angry old man on the ridge. People thought I was paranoid. They didn’t know I was standing guard over a peace treaty written in fear and gratitude.

I’m older now. Toby’s grown and lives where the lights are bright and the woods are far. But I’m still here. Some nights, when autumn sharpens the air, I smell wild sage and wet fur on the wind. Sometimes—high on the ridge—I hear a slow, deliberate knock: thump… thump… I don’t investigate. I pour a second cup of coffee, set it on the railing, and nod into the dark.

Because I learned the truth the town still calls a miracle: the woods aren’t empty. They are governed. And the king doesn’t always rule with teeth. Sometimes he rules with restraint—and the rent comes due in silence.