American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

1) The Arrival: Shadows in the Sun

Texas, 1945. The spring air at Camp Swift hung thick with dust and distant cattle calls. Inside the medical barracks, forty German women waited, silent as stone, faces hollow as winter branches. Captain James Morrison, an army doctor and former country physician from Oklahoma, entered expecting routine examinations. He had treated thousands of prisoners—soldiers, sailors, airmen. But when the first woman stepped forward and removed her threadbare uniform, Morrison’s hands stopped midreach. What he saw beneath that fabric would haunt him for the rest of his life.

.

.

.

The war in Europe had ended three weeks earlier. America celebrated with church bells and ticker tape. But at Camp Swift, sixty miles east of Austin, the war’s aftermath arrived in cattle cars and military transports. These women came from a labor camp near Bremen, captured during the Allied advance through northern Germany. Most were between eighteen and thirty-five, auxiliary workers in factories making uniforms and bandages for the regime’s forces. The Geneva Convention called them prisoners of war. Morrison saw something else—human beings on the edge of survival.

Lieutenant Sarah Chun, the camp’s head nurse, stood near the entrance, her composure replaced by carefully controlled anger. “Sir,” she said quietly, “I think you should know what we’re dealing with before you begin.” Her preliminary report was precise, clinical, but Morrison could read the emotion bleeding through the medical terminology: severe malnutrition in thirty-seven cases, advanced tuberculosis in twelve, untreated fractures in eight, infections that had spread through tissue and bone. “That’s not all,” Chun added softly. “Three of them are pregnant. Two are in their third trimester. None have received prenatal care.”

2) The First Examination: Beneath the Surface

Morrison’s heart tightened. Pregnant prisoners of war—women who had crossed the Atlantic in cargo ships, been transported in railway cars, marched through processing centers, all while carrying children. Regulations said nothing about this. The Geneva Convention outlined rules for prisoner treatment, but Morrison could not recall a single clause addressing expectant mothers in custody.

He approached the first cot. The woman was perhaps twenty-two, blonde hair cut short and uneven, hands resting in her lap, knuckles white with tension. Morrison spoke in careful German, learned from his grandmother back in Oklahoma. “I’m a doctor. I need to examine you to make sure you’re healthy. Do you understand?” She nodded, her eyes blue and ringed with shadows so dark they looked like bruises.

When she removed her jacket, Morrison saw ribs pressing against skin like ladder rungs, collarbones sharp enough to cast shadows. Her arms were covered in old bruises, yellow and green at the edges, fading but still visible. Her breathing was shallow and labored, with a wet rattle deep in her chest. Her fingernails were split and ragged, the beds stained with chemicals. “Have you been coughing?” Morrison asked. “Yes,” she whispered. “For months.”

He made notes: probable tuberculosis, severe malnutrition, chemical exposure consistent with factory work. With each examination, the picture grew darker. By noon, Morrison had examined fifteen women. All showed signs of prolonged starvation. All had untreated medical conditions that ranged from serious to life-threatening. Several had injuries that had healed incorrectly—broken bones set at wrong angles, leaving permanent deformities.

One woman had a compound fracture in her left arm that had mended without surgery, leaving her with limited mobility and constant pain. Morrison stopped at the twentieth examination and walked outside into the blazing Texas sun, trying to steady himself.

3) Breaking the Rules: Mercy Over Regulation

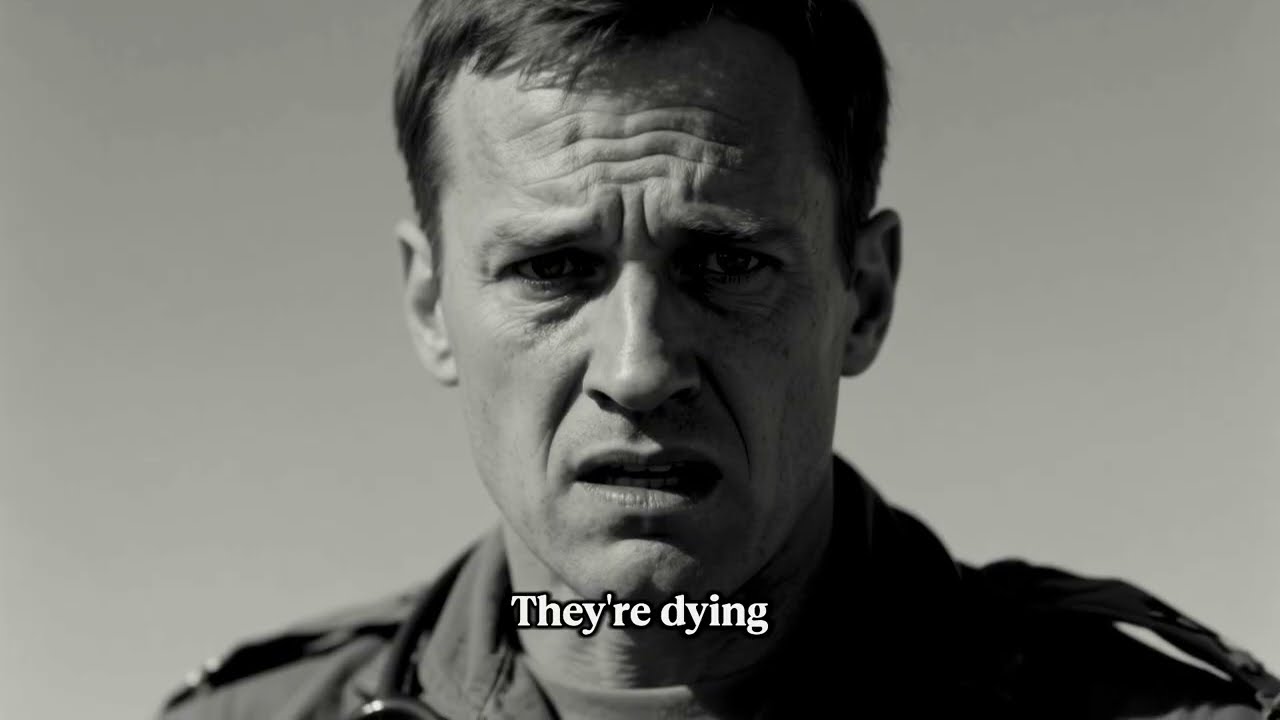

Chun followed him out, handing him a cup of coffee. “They’re dying,” Morrison said, voice rough. “Half of them have tuberculosis. The others are so malnourished they’re at risk of organ failure. And those three pregnant women…” He couldn’t finish. Chun nodded. “I’ve already sent word to headquarters. They’re bringing in additional supplies and staff.”

But Morrison shook his head. “Supplies won’t be enough. These women need intensive care. Some need surgery. And those pregnancies are high risk. Without immediate intervention, we could lose the mothers, the babies, or both.”

Regulations were clear: prisoners of war received adequate medical care as defined by military standards. Adequate meant treating acute injuries, preventing outbreaks, maintaining basic health. It did not mean intensive intervention. It did not mean prioritizing prisoner care over military personnel. But Morrison had not become a doctor to follow regulations. He’d watched his father die of appendicitis when help was too far away. He had sworn never to feel powerless again.

That afternoon, Morrison filed an emergency request with the base commander for permission to transfer critical patients to the hospital, to allocate more staff, to obtain specialized medications. The response came back within two hours: request denied. Resources were limited; supplies were earmarked for combat troops, not prisoners. Morrison was authorized to provide basic treatment within the barracks. Nothing more.

Morrison read the response three times, jaw tightening. Then he folded the paper, placed it in his desk drawer, and walked back to the barracks.

4) Creating a Hospital: Defying the System

That evening, Morrison broke the first regulation. He requisitioned medical supplies marked for military personnel and diverted them to the prisoner barracks—antibiotics, vitamins, clean linens, proper bandages. He signed forms with creative descriptions that would pass through the chain without raising questions.

The next morning, he broke the second regulation. He brought in civilian doctors from Austin, colleagues who understood that medical ethics transcended nationality and politics. They arrived quietly, carrying their own equipment, asking no questions about authorization or payment.

By the third day, Morrison had transformed the barracks into a functioning field hospital. He set up sections for different conditions: one area for tuberculosis patients, isolated to prevent spread; another for malnutrition cases, with careful feeding schedules; a third for the pregnant women, monitored around the clock.

The base commander learned of Morrison’s unauthorized activities. On the fourth day, he summoned Morrison to his office. “You’ve diverted military supplies, brought in unauthorized personnel, exceeded your authority. Do you have anything to say in your defense?”

Morrison stood at attention. He could apologize, protect his career, maintain discipline. Instead, he said, “Sir, with respect, those women are dying. I took an oath to preserve life. That oath doesn’t come with footnotes about nationality or prisoner status.”

The commander studied him, then finally said, “You’re a real pain, Morrison. But you’re not wrong. I’m issuing you authorization for continued intervention. If this blows up, I’m throwing you under the bus. Understood?”

“Understood, sir.”

5) Fighting for Life: The Long Nights

Morrison assembled his expanded medical team: three civilian doctors, seven nurses including Chun, two medics. The work was relentless—dawn to midnight, seven days a week, adjusting medications, monitoring vital signs, making countless small decisions.

Tuberculosis cases responded slowly to antibiotics. Malnutrition cases required delicate management. Morrison designed feeding schedules that gradually increased caloric intake, balancing nutrition against risk. He watched weights climb, flesh slowly covering bones.

But the pregnant women worried him most. Margot’s preeclampsia remained unstable. Helena showed signs her baby wasn’t receiving enough nutrition. Anna developed an infection threatening both her life and her child’s.

Morrison consulted with Dr. Patricia O’Brien, an obstetrician from Austin. She arrived, examined the three women, and delivered her assessment: “The first one needs to deliver within forty-eight hours. The second might last a week. The third needs immediate surgery.”

They operated on Anna first. The infection had spread; abscesses needed draining. Morrison assisted O’Brien, hands steady despite cramped conditions. Chun monitored anesthesia. The surgery lasted three hours. Anna’s vital signs stabilized.

Margot’s condition deteriorated overnight. Her blood pressure spiked; she began experiencing seizures. Morrison made the decision at four a.m.—emergency caesarian section. O’Brien arrived within thirty minutes. They worked by lamplight. The baby came out small and blue, not breathing. Chun suctioned the infant’s airways; a thin wail pierced the barracks. The baby’s color shifted from blue to pink. They named him Thomas, after Morrison’s father.

Helena delivered four days later, her daughter arriving small but healthy. Anna, recovering from surgery, delivered three weeks later—a son, screaming into the world.

6) Ripples of Compassion

By midsummer, the transformation was visible. Women who had arrived skeletal now showed the soft curves of proper nutrition. Faces carried color. Tuberculosis patients recovered. Broken bones had been set and splinted. Infections cleared. Three babies slept in makeshift cribs, watched over by mothers who had been given a chance at survival.

The other prisoners noticed. German soldiers in adjacent compounds heard about the American doctor who broke regulations to save enemy lives. Word spread through the POW network. Morrison became a symbol—a contradiction: a nation that could wage total war with industrial efficiency, yet whose doctor would risk court martial to save women from the defeated regime.

One evening in late August, Morrison sat outside the barracks, watching the Texas sunset. Chun joined him, carrying two cups of coffee. “Forty women,” Chun said quietly. “All alive, all recovering.”

Morrison nodded. The number felt both enormous and impossibly small. Forty lives saved against millions lost. A tiny victory in a war that had consumed continents.

“Do you ever wonder if it was worth it?” Chun asked. “Breaking all those rules, risking your career, fighting bureaucracy?”

Morrison thought about Margot, about Thomas’s first breath, Helena’s daughter’s cry, Anna’s son’s vital rage. He thought about the women who could now walk unassisted, who laughed, who sang German folk songs in the evenings when they thought no one was listening.

“Every single day,” Morrison replied. “And every single day, the answer is yes.”

7) Legacies: Lives Saved, Lessons Learned

The war ended in the Pacific in September. The world began reconstruction, counting the dead, building peace from the ashes. The German women were repatriated, sent back to a homeland that no longer existed as they remembered. Morrison received letters occasionally—Margot found her husband alive; Helena became a teacher; Anna immigrated to Canada.

Morrison stayed in the army for five more years, then returned to Oklahoma, opening a practice in the same rural area where his father had died. He never spoke publicly about Camp Swift or sought recognition. But in his office, barely visible, he kept a photograph: forty women standing together in Texas sunlight, faces showing hints of health, eyes carrying hope. Three babies held in their mothers’ arms. In the back corner, Captain Morrison and Lieutenant Chun, white coats bright against the dust-brown landscape.

Years later, historians found Morrison’s detailed medical records—his unauthorized requisitions, his careful documentation of every decision that violated regulations in service of his oath. He was reprimanded twice, recommended for court martial once, and ultimately received a commendation for exceptional medical service.

But the records could not capture what Morrison understood: the forty lives saved at Camp Swift represented something larger than medical intervention. They represented a choice—one man, one moment, prioritizing the fundamental obligation of medicine over the convenient classifications of wartime politics.

In Germany, these women had been workers for the regime. On the Atlantic crossing, they were prisoners. But in the Texas barracks, under Morrison’s care, they became simply what they always were—human beings whose lives mattered, whose suffering demanded response, whose survival was worth fighting for, regardless of uniform or nationality.

The babies grew up: Thomas became an engineer, Helena’s daughter a physician, Anna’s son a teacher. They lived lives their mothers had nearly lost, contributed to the slow rebuilding of a shattered world. Though most never knew the full story of their births, they carried forward something essential—proof that even in the darkest times, individual choices of compassion could ripple forward through generations.

Morrison died in 1983 at age seventy-four. His obituary mentioned his military service, his career in rural medicine, his dedication to his community. It did not mention Camp Swift or the forty women or the rules he broke. But at his funeral, three old women attended, traveling from Germany and Canada. They placed forty white roses on his casket before departing. Morrison’s wife, who had heard the story late one night, simply smiled and said they were people whose lives her husband had touched.

In the Texas heat of 1945, Captain James Morrison saw women dying and made a choice—not because regulations authorized it, not because anyone would reward or recognize it, but because he was a doctor. And doctors save lives. Some obligations transcend the classifications of war and peace, victor and defeated, us and them.

Forty lives, three babies, one man who understood that the measure of civilization is not how we treat our friends in times of peace, but how we treat our enemies in times of crisis. The sun set over Camp Swift that August evening, casting long shadows across the compound. Inside, women slept peacefully for the first time since their capture, babies nursed at their mothers’ breasts, and Captain Morrison sat outside drinking coffee with Lieutenant Chun, knowing he had broken every rule in the book—and that he would do it all again, without hesitation. Because some things are worth fighting for, even when no one is watching and history may never remember your name.