BIGFOOT KILLED MY FRIEND IN FLATHEAD FOREST – I HAVE THE PROOF THEY’RE HIDING

Amber in the Ice (Flathead, February 2025)

Chapter 1: The Hospital Interview

Detective Walsh sat in the chair by my hospital bed like he’d been carved there—hands folded, notebook open, face neutral in the way men learn to wear when they’ve heard every kind of lie and every kind of grief. My hands wouldn’t stop shaking even though they’d wrapped them in gauze three hours ago, even though the frostbite specialist had promised I’d keep all my fingers. The trembling wasn’t from cold anymore. It was from the memory of a headlamp beam cutting through a snow cave and landing on something that should not exist.

.

.

.

I tried to describe the sound first, because the sound is what I hear in my dreams. A growl, but lower than any bear, resonant like an engine idling inside a chest too big for the space it occupied. When I said that, Walsh’s pen slowed. When I said the eyes reflected amber—not the green-gold flash of a bear’s tapetum, not the dull shine of a deer—his eyebrows lifted like he was fighting an involuntary reaction. He kept asking if I was sure. If I was absolutely certain. And I wanted to scream that I’d never been more certain of anything in my life, even if the photos on my phone had corrupted when I dropped it in the ravine, even if Tom’s camera had smashed during the fall, even if all we had left were nightmares that started at exactly 4:17 a.m.

Walsh wanted a neat answer that could be stapled to a report. Hypothermia hallucination. Panic. A bear, unusually large, unusually aggressive. Anything that kept the world in its familiar shape. I could tell by the way he listened that he was deciding where to put me: reliable witness or traumatized man spinning a story because truth was too heavy to carry alone. But the truth didn’t care where he put me. The truth was that Tom Mitchell was dead, and something had been waiting for us in the ice.

I told Walsh I needed to start seven days earlier, back when this was supposed to be a simple three-day backcountry ski trip. Back when I was still Ryan Caldwell, thirty-four, an environmental consultant from Kalispell who’d grown up in these mountains and believed—like a fool—that familiarity was a kind of armor.

Chapter 2: The Solo Decision

I’d planned the trip for months, watching avalanche forecasts the way some people watch stock prices, waiting for that clean window when danger dropped to moderate and the weather promised cold, stable nights. I’d invited Danny Reeves and his girlfriend, Sophie Chen, both experienced backcountry skiers who’d done trips with me for years. The night before departure, Danny texted: Sophie had the flu. They were out. Any sensible person would have called it off. Going solo into the Flathead in February is the kind of decision that ends up as a headline or a cautionary tale.

But I’d been drowning in work—endless impact assessments, stakeholder meetings, computer screens—and I needed the mountains the way lungs need air. I told myself I was prepared. I knew the drainages. I knew the shelters. I knew the emergency routes. And beneath all that logic was something uglier: stubbornness. The refusal to let my life be dictated by other people’s illnesses and my own loneliness.

The trailhead was off Highway 2 near Essex, where a logging road turned into a snow-covered track after a quarter mile. I started skinning up at 9:47 a.m. on February 11th, temperature twelve degrees, sky a hard blue that hurt behind goggles. The only sounds were my skis sliding through powder and my breath crystallizing. The endorphins hit early, that clean narcotic of movement in cold air, and for the first time in months I felt like my body belonged to me again.

I climbed for six hours with a forty-pound pack and reached a protected saddle at 4:15 p.m., just as the sun dropped behind the ridge and painted the snow orange and pink. I pitched my four-season tent among whitebark pines, anchored it with snow stakes, melted snow for water, ate a freeze-dried meal, and watched stars come out in numbers that made the sky look textured. It should have been perfect. It should have been quiet in the peaceful way. Instead, the quiet felt empty—no owl calls, no small movements in the trees—nothing alive but me and a wilderness that seemed to be listening.

I didn’t let myself name that feeling. I crawled into my sleeping bag and told myself I was imagining things. People do that in the dark: turn normal silence into threat. The mountains punish imagination, I thought. They reward discipline. I fell asleep convinced I was still in control.

Chapter 3: Knocks in the Night

At 2:38 a.m. on February 12th, I woke to a sound I couldn’t place. A rhythmic thudding, not wind, not avalanche, not the quick skitter of a small animal. It came in spaced impacts that traveled—thunk… thunk… thunk—like something moving through the trees and striking trunks hard enough that the vibrations carried through snow and fabric. The spacing was wrong, too: thirty, forty feet apart, as if whatever made it covered ground in long, deliberate strides.

I pulled on boots, clicked on my headlamp, and unzipped the tent slowly. Cold hit me like a fist. The instant my face met the air, the thudding stopped. Not faded—stopped, like a hand had turned a dial to zero. I swept my beam across trunks and snow-laden branches. Nothing. No eyeshine. No movement. Just black timber and my own breath loud enough to shame me.

But I could feel it—the weight of attention, like something had leaned its focus onto my skin. I stayed there for a few minutes, trying to decide if I was being ridiculous, then zipped the tent and lay awake until dawn, waiting for the sound to return. It didn’t. Morning arrived clean and bright, the forest innocent as a postcard. I made coffee and forced myself to believe I’d heard branches falling, wind shifting, an elk moving through timber.

I skied the main bowl that day, a north-facing slope that held powder like a secret. The snow was perfect—face shots, smooth turns, the kind of flow that wipes your mind clean. By early afternoon my legs were pleasantly wrecked and I headed back toward camp thinking about lunch.

That was when I found the first track.

I’ve seen thousands of tracks. Elk, deer, wolf, lion, bear. I know the difference between an impression and a melt pattern. This was fresh—edges crisp, definition sharp—and it was enormous: three feet long, fourteen inches wide, four distinct toes and what looked like a heel pad. It compressed the powder six inches deep where I sank four in ski boots. The print sat twenty feet from my tent in an area I’d walked through that morning. Which meant it had appeared while I was out skiing.

More tracks led from timber toward my tent, circled it within eight feet of the door, then marched back into the trees. The stride was massive—over six feet between prints. My first reflex was to call it a bear because bear is the word that keeps your world intact. But bears have five toes and claws. Bears don’t leave heel pads like a person. Bears don’t walk in long, steady bipedal lines for fifty yards.

I took photos with my phone from every angle, used my ski pole for scale, and felt my hands start to shake for the first time. Not abstract unease now. Evidence-based fear. Something had come to my camp while I was gone and had studied it.

I should have packed right then. Skied out. Driven home. I didn’t. I told myself there was a rational explanation I just hadn’t found yet. Stubbornness is a powerful drug. I stayed.

Chapter 4: Whistles and Stones

That evening, as the temperature sank toward negative five, I stored my food in a bear canister thirty yards from the tent and tried to treat the day like an oddity. Then I heard the whistle. A long rising-falling note that echoed off ridge walls, almost human in shape but too clean, too loud, as if lungs the size of oil drums had pushed it. It came from upslope in timber above camp. A minute later it came again from a different direction, maybe two hundred yards left. My brain supplied the conclusion before I could argue: there were at least two.

I walked faster. A branch cracked behind me. I ran, dove into my tent, zipped it like nylon could become a wall. Outside, the sounds escalated: trees being struck again, closer now, wood splintering, then a scream—ten seconds long, rising into a pitch that made my teeth hurt, ending abruptly as if cut off with a knife.

I tried my satellite phone through the vent flap, tilting it toward slivers of sky. Searching. Searching. No signal. I had no weapon beyond a small folding knife. The night became a cycle of silence and sudden violence—rocks thumping into snow near my tent, then rocks hitting the tent itself hard enough to make the fabric shiver. Rocks thrown. That’s what my mind kept returning to. Throwing requires intent. Intent requires something I didn’t want to consider.

Dawn on February 13th revealed the aftermath. The bear canister hadn’t been opened—it had been thrown forty feet into a tree and lodged in branches. Tracks covered the area in systematic loops. I counted at least three sizes—three individuals—and one set was smaller, maybe juvenile. The idea of a family group did something ugly to my understanding. Social animals. Protective behavior. Intelligence.

I packed with shaking hands and started down the drainage at 8:45 a.m., determined to get back to the trailhead. Six miles. Easy, on paper. But within a quarter mile my landmarks were wrong. The creek crossing I remembered wasn’t there. The lightning-struck tree that always marked the halfway point was missing. My compass said southeast—correct. My GPS screen was cracked and glitching, jumping my position in half-mile hops. My phone, charged the night before, was dead.

I kept skiing because drainages lead to valleys, valleys lead to roads. Ninety minutes later I found the second set of tracks crossing ahead—fresh, fifteen minutes old—those same massive prints cutting across my line like something pacing me. I changed direction, cut cross-slope to break the pattern, and an hour later found another set of tracks that had passed within twenty feet of where I stood, so fresh I could see ice crystals collapsing back into the compression. Whatever was making them had been close enough to touch me. I hadn’t heard it.

The sun began dropping early, and I realized with cold clarity that I was going in circles. I found my own ski tracks. I stood there staring at proof of my confusion when I saw them.

Two figures, upright on a ridge seventy yards away. Massive. Broad. Fur dark against snow. They didn’t move at first. They simply watched, as if waiting for me to understand what the tracks had been telling me all along.

One stepped forward—too fluid for that size—and the other raised an arm holding a rock the size of a basketball. The rock arced toward me with clean, terrifying accuracy. I dove. It hit where I’d been standing and exploded powder into the air like a mortar strike.

I didn’t try to be smart. I ran.

Chapter 5: The Overhang

I skied downhill faster than I ever had, taking risks that felt suicidal, letting gravity do what fear demanded. I heard crashing behind me through timber, heavy movement that matched my speed in impossible ways. When the slope flattened, I slowed and looked back. Nothing visible. But I knew, with the kind of certainty that isn’t thought but instinct, that they were still there.

I found a small cave—more an overhang—at 4:52 p.m., a boulder wedged against a cliff face creating a shallow pocket protected from wind. I crawled inside, pulled my pack in, and sat watching the entrance as light failed. I didn’t make a fire. I couldn’t risk smoke or glow. I ate energy bars, did cramped exercises to keep warmth in my muscles, and waited for darkness like a sentence being carried out.

When night fell, I heard breathing outside. Wet, deep breathing, back-and-forth pacing in front of my shelter. Once, a shape blocked the stars and leaned close enough that the stench rolled in—wet dog, rot, something sour and animal. Then the whistles came again, multiple directions, like communication. The idea that they were coordinating wrapped around my throat.

By 3:00 a.m. I couldn’t feel my toes. My fingers went numb inside gloves. Hypothermia crept in with a calm inevitability. I understood the choice: stay and freeze, or move and risk whatever waited. At 4:17 a.m., I decided cold was the more certain death. I packed by feel, crawled out into air that hurt to breathe, clipped into skis, and started moving in near-darkness guided by pre-dawn glow reflecting off snow.

They were on me immediately—crashing pursuit, whistles, the thump of weight. I fell twice. The second fall, something grabbed my jacket from behind. Fabric tore. My ski came off. I kicked free and skied on one ski, dragging the other leg through powder because stopping meant dying.

Sunrise came at 7:29 a.m., and I was beyond exhaustion, beyond fear, operating on the raw fuel of survival. I stopped in a small clearing and turned in a circle, mountains unfamiliar, terrain wrong—until I saw the tracks that saved my life.

Snowmobile tracks. Human tracks. Civilization carved into snow.

I followed them west like they were a lifeline.

Chapter 6: The Cabin and the Watchers

At 11:15 a.m., I found a forest service cabin—locked for winter. I broke a window with a rock, climbed inside, and nearly cried at the smell of dust and old wood. There was canned food, bottled water, and an old radio hardwired to a solar panel. I grabbed the mic and called on every channel until, at 11:47 a.m., a ranger answered: Bill Peterson, stationed twenty miles away.

I told him I was lost and hurt. He asked for location. I couldn’t give coordinates—my GPS was unreliable—only described the cabin and the broken window. He said he knew it. Help in three hours, if roads were clear. I said three hours might be too long because something had been hunting me. He asked if I meant bear or lion. I said no. I said bigger. There was a pause, then his voice shifted into that calm tone people use when they’re trying not to sound scared. Stay inside. Keep the radio on. Help is coming.

At 12:33 p.m., I saw them from the cabin window. Three figures at the treeline a hundred yards away, watching the cabin like it was a curiosity. In full daylight their fur looked dark reddish-brown, like old blood mixed with ice. Their faces were flat and almost human but wrong. Eyes too far apart. Mouths too wide. The largest one was at least nine feet tall, wide enough to look carved out of muscle. They watched for five minutes, then turned and walked away, casual and unhurried, like I wasn’t worth the effort.

Rescue arrived at 2:41 p.m.—Bill Peterson and Tom Mitchell on snowmobiles. I ran outside babbling, pointing at the trees. Bill used the trauma voice: you’re safe, we’re here. Tom looked at the ground instead and said, “Bill, you need to see this.” Tracks circled the cabin. Huge. Not bear. Not anything he recognized. Bill’s face changed as he studied them, and I watched a man’s skepticism crack into something else.

Then the growl came from the trees—deep, resonant, close. Bill’s head snapped up. “We leave,” he said. “Now.”

They put me on the back of Tom’s snowmobile. We started toward the ranger station and got two miles before Tom stopped and pointed ahead. Three figures stood shoulder-to-shoulder across the trail, blocking it. The largest stepped forward. Tom gunned the engine, tried to angle around, but the terrain was too steep. We would have to go through them or turn back.

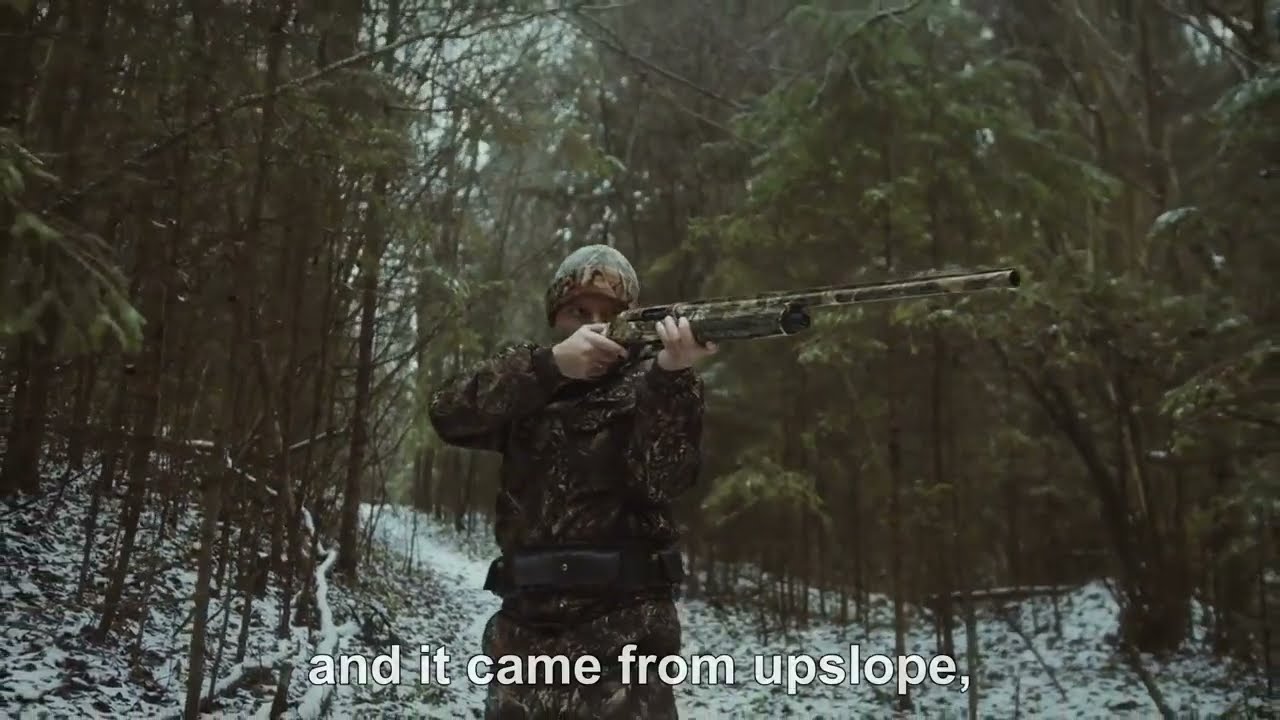

We turned—away from the station, away from help—up a different drainage. We rode hard, engines screaming, and twice I saw shapes running through timber keeping pace even though we were doing thirty miles an hour. Tom aimed for a cave in a rock face, a dark opening across a meadow. We ditched the snowmobiles and ran for it. Tom had a rifle from his storage box. Bill had his service pistol. I had a rock.

Inside, the cave opened into a chamber about twenty feet across. Bill got on the radio demanding immediate backup, helicopter if possible. Dispatch argued. Bill shouted. Then the radio cut out—dead—despite full batteries that morning.

At 4:17 p.m., we heard them outside. Breathing. Rock movement. Tom raised the rifle. Bill’s pistol looked absurd in his hand.

The first one ducked through the entrance at 4:31, hunched to fit under the ceiling. Its fur was matted with ice. Its eyes reflected amber when Tom’s beam hit them.

Tom fired. The cave exploded with sound. The bullet hit the creature’s shoulder. Dark blood sprayed. It didn’t stop. It roared and stepped forward. Tom fired again. Three more rounds. It staggered but kept coming. Bill fired his pistol. I screamed without realizing it.

Tom’s rifle clicked empty. The creature reached out with a hand—fingers thick as broom handles—and lifted Tom off the ground by his jacket like he weighed nothing. It studied him for a beat, eyes old and aware, then threw him across the cave. Tom hit the back wall with a sound like dropped weight and crumpled, not moving.

Bill grabbed my arm and we shoved into a narrow crevice at the back. Something grabbed my ankle. My boot came off in its grip. We fell through into a smaller chamber where the creature couldn’t fit. We listened to it rage, tearing at rock, breathing loud enough to feel. Then we climbed a narrow chimney to another exit above, and waited until dawn because there was nothing else left to do.

Tom was dead. We both knew it. But knowing didn’t make it real until we saw him again in morning light.

Chapter 7: The Official Story

We escaped on Bill’s snowmobile at first light. A mile out, I saw all three on a ridge watching us leave, still and silent as monuments. Bill gunned the engine and didn’t stop until pavement, until vehicles, until people. Safety felt thin, like paper over a fire.

The formal search began later that morning. We led them back despite frostbite, despite shock, because Tom was out there. In the cave they found blood and drag marks deeper into the passages. They found Tom wedged in a narrow crack three hundred feet in, torn apart and partially consumed. The sheriff pulled me back before I saw too much, but I saw enough. Enough to understand that whatever did this wasn’t a confused animal lashing out. It was a predator operating with strength and confidence.

The official report called it a grizzly attack. Rare early emergence. Tracks exaggerated by snow conditions. Panic-induced misinterpretation. They needed a label that fit wildlife manuals and liability statements. Bill tried to fight it. His photos were blurry. His testimony was “unreliable under stress.” My phone photos were corrupted. Tom’s camera was smashed. Evidence dissolved the way it always does in winter: buried, washed, broken, explained away.

Now I’m in a hospital room with Walsh asking careful questions, trying to pin reality down with words. But words don’t hold weight the way a three-foot footprint does. Words don’t carry the smell of wet fur and rot. Words don’t recreate amber eyes in a headlamp beam.

I can tell you what I know, the only truth that matters: something lives in those mountains that is not supposed to exist. It moves with intent. It hunts with patience. It uses the terrain like it owns it. And if you’re unlucky, it won’t just kill you. It will let you live long enough to understand what it could have done—long enough to carry the fear back to civilization like an infection.

That’s why my hands shake even in a warm hospital room. That’s why I wake at 4:17 a.m. every night. Not because of cold, not because of trauma alone, but because part of me is still in that cave, listening to breathing in the dark and realizing, with awful clarity, that the wilderness has rules we don’t write.