Bigfoot Saved Me From Falling into Frozen Lake, Then It Did Something Strange – Sasquatch Story

THE FEATHERS AND THE WATCH

A northern Michigan winter tale in seven chapters

Chapter 1 — The Lake I Thought I Knew

I never expected to owe my life to a Bigfoot. Even now, writing that sentence feels like stepping onto thin ice all over again—one wrong move and the world will break beneath you. But three winters ago, up in northern Michigan, that is exactly what happened. I drove to a lake I’d known since childhood, the kind of place you return to when you want to remember who you were before bills and noise and obligations started eating the edges of your life. It was late January, a Friday afternoon, and the temperature had been below freezing for weeks. I told myself the ice would be safe. I told myself I’d earned a quiet weekend.

.

.

.

The lake sat back in the woods with only one access road, a lonely boat launch that, in summer, would be crowded with trailers and coolers and shouting kids. In winter it becomes something else: a white plain under pale sky, bordered by pines and birch, so silent you can hear your own breath. That day, the parking area was empty. I saw old snowmobile tracks and deer prints, but no other vehicles. No other people. I liked it that way. No phone service out there, no scrolling, no reminders that the world keeps demanding parts of you. Just the forest and whatever fish might still be moving under ice.

I loaded my gear onto a plastic sled—portable shelter, gas auger, rods, tackle, cooler—and checked my safety kit out of habit. Ice picks around my neck, cleats on my boots, the little practices that make you feel like you’re in control. I’d had a close call years earlier and promised myself I would never treat ice like a guarantee again. Promises are easy until you convince yourself you’re the exception.

The trail from the lot to the lake was packed down by snowmobiles. Chickadees chattered somewhere above. A woodpecker tapped at a dead trunk like it was counting seconds. When I stepped onto the ice, it looked solid. Snow lay four inches deep on top, hiding the surface like a blanket. I walked about two hundred yards from shore to a spot I’d fished for pike and perch before, set my shelter, and fired up the auger. The motor’s growl felt rude in that quiet, but I wanted holes drilled before the light faded. I planned three holes in a triangle, options depending on how the fish were moving.

The auger bit into the ice and chips flew up—white, clean, and then… too wet. The ice had a gray tint I should have recognized. I didn’t. I was focused on routine, on the comfort of doing what I’d done a hundred times. The blade punched through after about eight inches. Eight inches. That should have been my second warning. Safe ice depends on a lot of factors, and “I’ve been cold for three weeks” isn’t a contract the lake signs. I should have packed up right there. Instead, I thought about the hour drive, about stubborn pride, about how ridiculous it would feel to leave without even dropping a line.

Then I heard the first crack—soft, like a branch snapping somewhere far away. I paused, listened, blamed it on ice settling. The second crack was louder, closer. I felt the surface shift under my boots in a way that made my stomach drop like an elevator cable had snapped. I looked down and saw a thin line forming between my feet, spidering outward.

I had seconds. I dropped the auger and tried to flatten my weight like you’re supposed to—spread out, crawl, don’t panic. I was too slow. The ice gave way under my left foot. Cold water slapped my leg. Then the line widened, the sheet fractured, and suddenly I was waist-deep, then chest-deep, then gone—swallowed by black water under white ice like the lake had decided I’d been arrogant long enough.

Chapter 2 — The Black Under the White

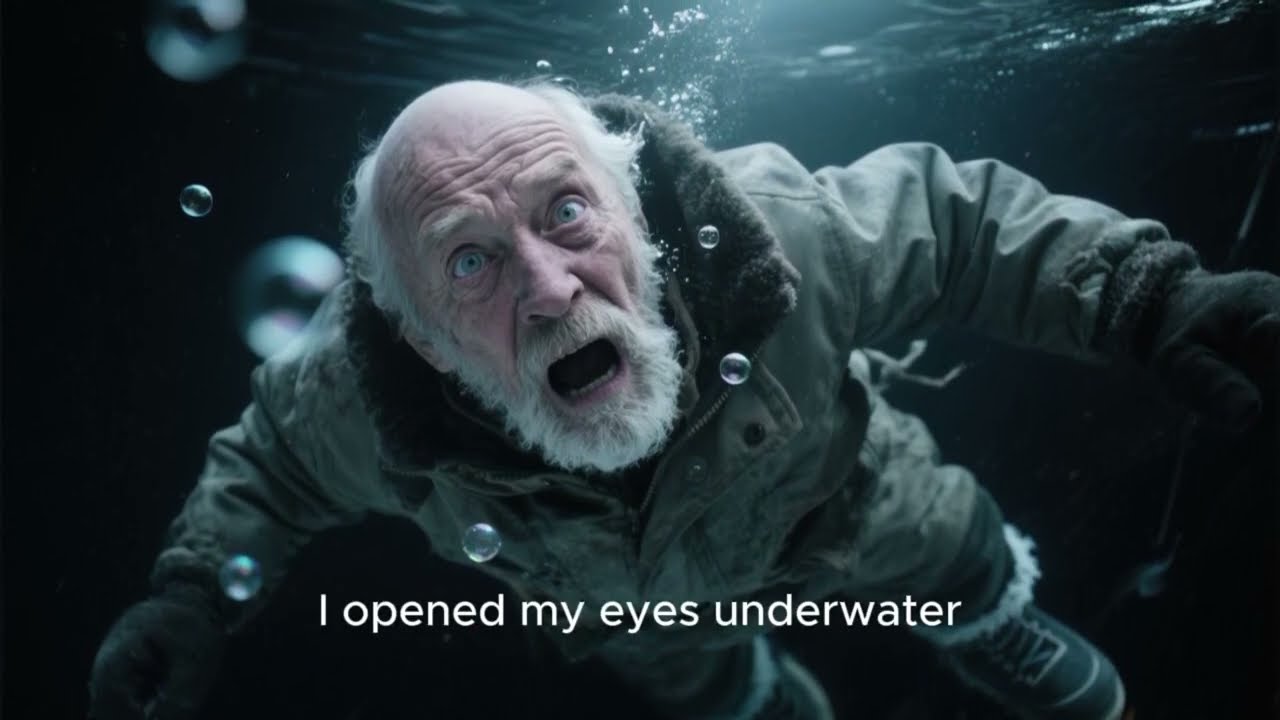

People don’t understand what cold water does until they meet it. It isn’t discomfort. It’s violence. The shock hit so hard it stole the air from my lungs. My muscles seized. My winter coat and boots drank water and turned into weights that wanted to pull me down forever. I tried to kick toward what I thought was the surface, but my legs moved like they belonged to someone else, sluggish and disobedient. I opened my eyes and saw nothing but darkness and drifting silt, the underside of ice faintly visible like a ceiling I couldn’t reach.

The current—if you can call it that—pushed me sideways. I scraped along the ice, searching for the hole I’d fallen through. But everything looked the same under there, smooth and merciless. There was no “up,” no “down,” only panic and the steady widening burn in my chest that meant my body was about to inhale whether I wanted it to or not. Black spots crowded my vision. The thought that came, clear as a bell in the middle of chaos, was simple: This is how people die out here. Quietly. Unfound until spring.

Then something grabbed me. Not my hand, not my wrist—my coat, the back collar, as if someone had hooked me like a fish and decided I was worth keeping. I felt an incredible upward force. My head broke the surface and I sucked in air so hard it hurt, coughing and choking, water spilling from my mouth and nose. I couldn’t see what had me. I only knew I was moving—dragged across rough ice away from the hole, scraping, sliding, the world a blur of white and gray and pain.

Suddenly I was on shore, dumped onto snow and leaf litter at the treeline. I lay on my side shaking so violently my teeth rattled. I couldn’t control my hands. I couldn’t stop coughing. Every breath felt like knives. I blinked hard, trying to clear my eyes, trying to focus on the shape looming over me.

That’s when I saw it.

It stood tall enough that my brain refused to accept the measurement at first—eight feet at least, maybe more, thick dark reddish-brown hair longer and shaggier around the shoulders. Legs like pillars planted wide in snow. Huge hands with thick fingers and dark palms. The face held my attention the way headlights hold a deer: flatter than a gorilla’s, more human in proportions, broad flat nose, heavy brow, and eyes so dark they looked almost black.

Those eyes were watching me. Studying. Not hungry. Not enraged. Something else—an expression I couldn’t name because I didn’t have a category for it. The Bigfoot breathed hard, steam billowing into the air, as if it had exerted itself to pull me out. We stared at each other, and I was too shocked and cold to be afraid. I tried to speak and couldn’t get words past my shaking jaw.

The Bigfoot tilted its head slightly and made a low grunt—not a threat, more like a question. Then it turned and moved into the trees with speed that didn’t match its size. It disappeared so fast it felt like the forest had swallowed it.

For a moment I thought that was the end: rescued, then abandoned. I was still in danger. Hypothermia doesn’t care if you’ve survived drowning. My hands fumbled at my soaked coat zipper, my boots, the laces—everything felt like trying to work tools with mittens made of stone. The cold was climbing into my bones, and I could feel my strength leaving in quick, brutal increments.

Chapter 3 — The Firewood Lesson

I heard movement behind me and turned, bracing for anything. The Bigfoot came back. In its arms it carried dead branches and sheets of bark—birch bark, the pale papery kind that ignites even when conditions are bad. It approached slowly and dropped the bundle beside me, then stepped back and watched.

It wasn’t random wood. It was selected. Dead, dry branches. Bark that would catch. The Bigfoot made the low grunt again and gestured toward the pile with one massive hand. The movement was deliberate and clear. Fire.

The fact that it understood what I needed—understood the difference between survival and death in a Michigan winter—shook me more than the rescue itself. I nodded, not sure it recognized human gestures, but it seemed to. My coat pockets were soaked except one: a waterproof zipper compartment where I kept a lighter. My shaking fingers fought the zipper, then the lighter. It took me several tries to flick the wheel, but finally I got a flame. I shredded birch bark into thin curls, sparked it, and watched it catch like a promise.

The first warmth from that fire felt holy. I fed it twigs, then thicker sticks, building slow, careful, like I was reassembling my life one piece at a time. My hands burned with pins-and-needles as feeling returned. I could see ice crystals clinging to my beard. My pants were freezing stiff. I knew I needed to strip down, wet layers off, get clothing hung near heat. Embarrassment is a luxury hypothermia doesn’t allow.

The Bigfoot watched without moving, and there was no leering curiosity, no aggression. Just steady attention, as if it was monitoring a procedure. When I finally got down to underwear and hung my wet clothes on branches, I crouched close to the flames, shaking uncontrollably, trying to convince my body it wasn’t dying. The Bigfoot turned and walked into the forest again. My stomach tightened with fear—what if it left for good? What if the fire failed?

Ten minutes later it returned with larger logs, stacking them near the fire in a neat pile. Enough to last the night. Then it sat down about fifteen feet away, cross-legged against a tree trunk, facing me like a silent sentinel.

That was when I realized it wasn’t just helping. It was staying.

Chapter 4 — The Night Watch

The sun bled out behind the trees and the cold sharpened. The lake groaned and cracked as the ice contracted. Wind moved through pines, making them creak like old ships. I sat by the fire drying clothes, trying to think, trying to process the impossible. The Bigfoot remained almost motionless, turning its head now and then to listen into the forest behind it, as if it could hear things I couldn’t.

I tried talking—because what else do you do when you’re alive only because something that shouldn’t exist decided you were worth saving? I said thank you, over and over. I asked questions I knew were absurd. I told it I’d been coming to that lake since I was a kid. That I’d made a stupid mistake. That I didn’t know how to repay what it had done. The Bigfoot didn’t answer in words, but it listened. I could tell by the way its gaze tracked my face and the way its head tilted when I spoke.

By evening my clothes were dry enough to put back on. Boots took the longest, steaming near coals. I ate two soggy granola bars that survived my dunking, chewing slowly to stretch the calories. I wondered if the Bigfoot was hungry, what it ate in winter, what kind of life it lived when the world froze. I felt a ridiculous guilt that I didn’t have enough to share.

I fought sleep. Hypothermia and exhaustion are a dangerous combination, and the fire could die if I nodded off too long. But adrenaline doesn’t last forever. Around midnight, the Bigfoot rose, walked to the woodpile, and placed several large logs onto the fire with careful precision, building it into something that would burn longer. Then it sat down again.

That simple act broke something in me—the last shred of fear that it might abandon me to the night. It wasn’t going anywhere. It was guarding me, the way a person guards a friend, the way a parent guards a child. Eventually, around one in the morning, I dozed. The fire blurred into orange. The Bigfoot became a dark shape against trees. Then sleep took me.

I woke to a hand on my shoulder. Not rough, not shaking me violently—firm and controlled. My eyes opened and the Bigfoot was crouched close, face nearer than it had been all night. The fire had burned down to coals. The Bigfoot grunted and gestured into the forest, then stood and walked a few steps, looking back to make sure I followed.

Every rational part of my brain screamed that following an eight-foot unknown creature into dark woods at four a.m. was insanity. But my rational brain had almost killed me on the lake. The Bigfoot had saved me and kept me alive. I trusted it the way you trust gravity: not because you understand it, but because it has already proven itself.

So I followed.

Chapter 5 — The Clearing of Shelters

We walked uphill through thick forest for about twenty minutes. The Bigfoot moved at a pace I could manage, stopping occasionally to let me catch up. Then the trees opened into a clearing on a small rise—half an acre maybe—hidden so well I could’ve walked past it a hundred times and never seen it.

And in that clearing were structures. Three of them. Low, dome-shaped shelters made from branches, bark, and leaves woven together like giant baskets. Not windfall piles. Not random debris. Built. Crafted. Placed in a deliberate triangle under overhanging pine boughs for shelter from snow.

The Bigfoot led me to the first and pulled back the entrance covering. Inside was a thick bedding mat—dried grass and moss layered and woven, edges raised, insulation arranged with care. It wasn’t merely a nest. It was a bed, designed by someone who knew cold and had beaten it year after year with skill. I looked back at the Bigfoot and got the distinct impression it was watching my reaction, proud in a quiet way. I nodded and murmured that it was impressive, beautiful. The Bigfoot made a soft purring sound, a satisfied rumble.

The second shelter was larger, its entrance facing east toward sunrise, with stones positioned where hot coals could be brought in to hold heat. The third was smaller and clearly used for storage—bundles of bark, stacks of moss, rolled animal hides, dried grass tied with plant-fiber cordage. Everything organized and protected from weather.

Then the Bigfoot showed me tools. A rock pile sorted by size. Bones arranged by type. It picked up a smooth granite scraper and demonstrated its use against wood. It held up a deer leg bone worked into a point, likely used for digging. Nearby were sticks with bark stripped, ends charred, notches carved—implements shaped by deliberate hands.

At the edge of the clearing, on a large oak, there were carved symbols in the bark—lines, circles, patterns that were too structured to be accidents. The Bigfoot touched them in sequence, making different sounds as it did, like it was reading or teaching. I stared, trying to memorize shapes I couldn’t interpret. Territorial markers? A calendar? Names? Stories? I had no way to know, but the act felt intimate.

It led me to a stream that hadn’t frozen, where stones were arranged into a kneeling platform. It demonstrated drinking—cupping water in massive hands. It gestured for me to try, and I drank cold clean water that tasted like it came from the center of the earth.

There was a fire pit too, ringed with blackened stones, with a stack of dry wood tucked under bark cover. The Bigfoot had fire. Not as a myth, not as a rumor—practically, deliberately, like a tool it understood.

And then it showed me something that made my throat tighten: a collection.

Chapter 6 — The Things It Found Beautiful

In a sheltered space lined with moss were objects arranged like a display. A worn blue glass bottle that caught morning light and glowed. Quartz crystals. Sheets of mica that split into thin, transparent layers. A perfectly round river stone. A piece of obsidian black as deep water. A fossil rock with shell imprints. A bird skull, cleaned and delicate, placed on a small pedestal of stones.

It picked up the blue bottle with both hands and held it to the light, turning it slowly like someone admiring art. It set it back in the exact same place. The precision was the point. This wasn’t hoarding. It was curation.

It handed me a quartz crystal to hold, watching my face as I turned it and let light fracture through it. When I gave it back, it placed it carefully among the others. Then it touched the bird skull gently, almost reverently, and made a softer sound—quiet enough that it felt like an emotion more than a vocalization.

Finally, it lifted a bundle of seven large feathers—rust-colored with white tips and dark bands, bound together with twisted plant fiber, dyed dark, tied in decorative knots that served no practical purpose. It placed the feathers in my hands and folded my fingers around them gently. When I tried to return them, it pushed my hand back with firm insistence.

It was giving me a gift. Not because it had to. Because it chose to.

I tucked the feather bundle inside my coat, protecting it like something sacred. The Bigfoot rumbled with that pleased sound again. Then it showed me another item—leather worked soft, with a claw, amber, small stones—something like jewelry it wore, personal and kept, shown but not offered. It was the first time I thought, with real weight, that this being had a private self. Preferences. Pride. Attachment.

We stayed in the clearing as the sun climbed. I noticed worn paths between shelters, bark stripped from a tree where it likely scratched, marks at heights no human could reach without climbing. It showed me how to weave additional branches into shelter walls to close gaps in bad weather, demonstrating the technique like a homeowner explaining improvements.

Then it began calling—louder than before. Not aggressive, but summoning. From deeper forest came responses from different directions. More than one. More than two. A community, perhaps, staying hidden, aware.

The Bigfoot looked at me and gestured toward the route we’d come. Time to go.

Before we left, I wanted to offer something back—something more than words. I took out my old Swiss Army knife and held it out. The Bigfoot accepted it carefully, examined it, opened tools one by one with surprising dexterity. It understood the screwdriver immediately. The can opener puzzled it until I mimed opening a can. Its eyes tracked every movement, learning fast.

When it finished, it held the knife in its fist and looked at me with something like gratitude.

Chapter 7 — The Watch That Came Home Ticking

The Bigfoot led me by a different route to a logging road I recognized. It stopped at the edge, turned to face me, and for a long moment we simply stood there, two beings from different worlds balanced on the thin bridge of shared survival. I wanted to say thank you in a way that mattered.

So I did something I hadn’t planned. I reached into my pocket and took out my grandfather’s pocket watch—silver case, white face, Roman numerals, old wind-up, engraved with his initials on the back. He’d carried it every day of his adult life. When he died, it came to me, and I’d kept it wound out of habit and loyalty.

I held it out. The Bigfoot looked uncertain until I opened it and showed the moving hands. I held it near its ear so it could hear the ticking. Its eyes widened slightly, and it took the watch with gentleness that didn’t seem possible in hands that could snap branches like twigs. It studied the gears, the engraving, the sweep of seconds. Then it tucked the watch into the thick hair on its chest as if placing it where it would be safe and close.

It pulled me forward into a brief, careful embrace. Then it placed a hand on top of my head, held it there for a few seconds—an act that felt like blessing more than curiosity—and stepped back. Without hesitation, it turned and walked into the forest, disappearing between pines as if it had never been there at all.

I made it back to my truck and drove home without telling anyone. Who would believe me? All I had was a feather bundle and an empty pocket where a watch used to be. Months passed, and I didn’t return to the lake. I was afraid of leading anyone there by accident. I was afraid of my own curiosity.

Then, six months later, hiking fifty miles from that lake on a trail I’d never walked before, I saw a rock stack beside the path—three flat stones balanced with a round stone on top. A marker I recognized from the clearing. I heard a low grunt in the trees and caught a glimpse of something large moving through brush a hundred yards away. I followed markers to an overlook I didn’t know existed, a view of untouched forest stretching for miles like a secret the world hadn’t spent yet.

And sitting on a rock by the trail was my grandfather’s watch. Still ticking. Cleaned, polished, and wound—as if someone had cared for it, kept time alive, understood what it meant to me.

I picked it up with shaking hands and held it to my ear. The tick was steady, strong. I whispered thanks to the trees, feeling foolish, but needing to say it anyway. The forest gave no answer except wind, yet I felt—deeply—that I’d been heard.

I’ve never seen that Bigfoot clearly again. But I still find markers sometimes. I still wind the watch every morning. And I still keep the feathers safe, because they are proof of something I can’t explain to the world: that in the deepest winter, when the lake tried to take me, something older than our stories decided my life was worth saving—and trusted me with a glimpse of its world.