Bigfoot Showed Me What Happened To 1,000 Missing Hikers – Disturbing Sasquatch Story

The Ravine Keeper

My name’s Frank Mercer. I’m seventy-two now, retired search and rescue out of Scammania County, Washington. I say that upfront so you know I’m not some kid chasing campfire stories. What I’m about to tell happened back in late September 2004, up near the south side of Mount St. Helens in the Cascades. Early fall—wet and cold, that gray drizzle that never quite turns into real rain.

.

.

.

It started like any other night after a search. Boots by the door, socks steaming near the baseboard heater, scanner muttering in the background. The smell of wet wool and coffee, porch light throwing a dull amber circle on the gravel. Ordinary.

Then came the three knocks from the treeline. Slow, measured. I shouldn’t be telling this, honestly, but it’s been years. People laugh when they hear “Bigfoot.” I did, too. I don’t have proof you’d accept. Just a memory. An old phone with a clip I won’t show anyone. And those three knocks I still hear when the house goes quiet.

We were three days into a search for a missing hiker—Tyler Green, thirty-two, solo, last seen at the trailhead. I was walking sweep with a younger deputy, Sanchez. Wet ferns slapped our pants, radios hissed in and out. The smell was wet earth and old ash, volcanic dust that never quite goes away out there. We stopped at a game trail crossing, listening somewhere upslope. Tap tap tap tap, like a piloted woodpecker. I told myself that’s all it was. Just a bird.

Back at the makeshift command post, one of the volunteers told a story about the thing in the woods that takes hikers. Sanchez snorted. “Yeah, yeah, the Bigfoot boogeyman.” I rolled my eyes. I’d heard it a hundred times—radio shows, tourists, kids. I told myself a grown man didn’t just vanish because of some Bigfoot rumor.

But that night, lying in my bunk in the trailer with rain ticking on the roof and the generator humming, I woke to silence so complete it felt wrong. Then three knocks, distant, like someone testing a door they couldn’t see. I told myself it was wind shifting a branch, but I still checked my boots and pack twice before dawn, as if I expected them to be gone.

A week after they called off Tyler’s search, I was back at my place outside Cougar, Washington. Early October 2004. The rain had turned steady and the air smelled like cedar and wood smoke. My wife had passed two years before. She’d left a woven berry basket hanging by the door, sage green paint flaking off the handle. I still used it for huckleberries. Domestic ordinary. I liked that.

One evening, the TV on low, local news talking about missing hikers in the Cascades. They flashed a list of names. I recognized three from my own calls. A thousand missing over the decades, they said. The number stuck behind my eyes like a splinter.

My neighbor Earl stopped by, boots muddy, smelling of diesel and hay. He leaned on my porch rail and said, “You hear that talk on the scanner? Some folks figure a Bigfoot’s got a taste for backpackers.” I laughed, but it came out thin. “Yeah, Earl. Bigfoot’s planning a buffet.” Inside, I watched the porch light throw that same amber cone across the rain-slick gravel. For a second, I thought I saw a tall shadow just beyond it. But then the refrigerator kicked on louder and I blinked, and there was only the treeline.

Before bed, I found the basket moved from its nail to the top step. Damp but upright, a single red maple leaf tucked inside. No wind could have done that. I put it back, locked the door, and lay awake listening for knocks that never came that night. I still don’t know who moved that basket.

Late November, first dusting of snow in town. I was at the sheriff’s substation in Stevenson. Paperwork, buzzing lights, burnt coffee. They had a corkboard in the hallway for missing persons. Hikers, hunters, runaways. A patch of them were outdoor folks—last seen on trail, date underneath. When you stepped back, it made a pattern. My stomach didn’t like that pattern.

One of the deputies slapped a cartoon on the board—a big hairy silhouette with a backpack in one hand, a hiker dangling from the other. “Scammania’s number one guide. Call Bigfoot Tours.” Everybody laughed. I forced a smile, gut twisted. “You’re the one always up near St. Helens,” Laramie said. “You seen our mascot yet? Bigfoot stealing your hikers.” “All I’ve seen are sloppy boots and bad weather,” I said. But the word tasted wrong in my mouth, like I shouldn’t joke with it.

On the drive home, snow mixed with rain, wipers squeaking. I kept thinking about that board, about how many pins there were. The heater blew that dry plastic smell. I cracked the window for fresh air and got hit with that wet dog, wet moss smell. Strong, like something big had just crossed the road. I stopped the truck, engine idling. Headlights washed over bare trunks and dirty snow. No movement, no tracks I could see.

Later that night, with the baseboard heater ticking and the old house settling, I heard three dull knocks again, more faint this time, like somebody knocking two doors down. I told myself it was the branch in the wind. I never went outside to check. I still wonder what I would have seen if I had.

By late January 2005, the cold had settled in. My place out by Cougar was quiet except for the wind running through the firs and the occasional pop from the wood stove. I was out by the shed splitting wood, breath fogging, hands numb. The sharp smell of fresh cut cedar and metallic cold air. Snow lay in crusty patches around the yard. I turned to grab another round and saw them—footprints. Not bootprints, bare, human-shaped but too long, too wide, with a big wide pad and no clear arch. They came from the treeline, stopped near my wood pile, and turned back. Snow around them melted a little, like whatever made them was warm.

My first thought was, “Some idiot out here barefoot.” My second thought, one I pushed down hard, was Bigfoot. I said it out loud just to hear how stupid it sounded. No way. This is Bigfoot stuff, Frank. Get a grip. I set my boot next to one print. Mine looked like a kid’s shoe beside it. My chest tightened. That wet dog, wet fur smell came in on the breeze again, mixing with cedar and smoke. And under it, something else—like turned earth, a riverbank after flood.

I followed the tracks toward the trees until they just stopped. Not faded, stopped. I told myself snow fell from the branches and covered the rest. I told myself that three times on the walk back to the house. Crunch of my own boots loud in the silence.

That night, the refrigerator’s hum sounded too loud. The house too small. I locked the door, then checked it again and again. Around midnight, just as I was drifting off, I woke to the distinct sound of three slow knocks from the direction of the shed. I lay there, heart hammering, telling myself it was the wind. I still don’t know why the wind would knock exactly three times.

Early May, snow mostly gone, everything wet and green again. I’d gone back on active rotation for search and rescue. Couldn’t quite retire. Not yet. This call was for two missing brothers, last seen heading up a side trail off Ape Canyon. We set up a base camp in a clearing. Creek rushing nearby, cold mineral water and fresh spring growth.

On the second day, I found what should have been good news—a campsite. Two tents still standing, zippers half open, a little propane stove cooled, mugs half full of coffee gone cold. No sign of a struggle. Just absence. What stopped me was the ring of stones stacked at the treeline. Not a fire ring. Three little towers, knee-high, flat rocks balanced too carefully to be casual. On top of each tower sat a small object from the camp—a spoon, a lighter, a folded bandana.

Beyond that, in the trees, that smell again. Wet fur, river mud, something musky, like an animal that lives alone. Sam, another volunteer, came up behind me. “Kids playing with rocks?” I stared at the towers. “Maybe someone’s marking a trail,” I said. He sniffed and made a face. “Smells like a zoo back here. Like Bigfoot took a bath.” He laughed, but it died quick. I didn’t say the word back to him. I didn’t need to. It hung there between us anyway.

That night in my tent, the creek’s rush turned to white noise. I woke because everything went quiet. Dead quiet. Then from the far side of camp, past the stone towers, came three knocks. The tarp over us rattled with each one. No one said anything over the radios. No one admitted hearing it. We never found those brothers. We found their car, their gear, their little stone towers, but not them.

I didn’t tell anyone about the towers or the smell or the footprints. What would I say? That I thought Bigfoot was collecting souvenirs? That maybe all those missing hikers hadn’t just gotten lost.

Earl came by one evening in mid June, bringing a six-pack and gossip from town. Another missing person report. A woman this time, vanished near the climber’s bivouac on the north side. She’d been experienced, had a GPS, a beacon, the works. Nothing worked when you didn’t come back. I asked if they’d found anything. He shrugged. “Just her pack,” he said, neatly set beside the trail, zippers closed, everything inside like she was coming right back. That’s the third one this year, Earl said. People are starting to talk. About Bigfoot, Frank. About something taking people. He laughed, but it was uneasy. I didn’t laugh at all.

By July, the missing posters on that board had grown again. I started waking up at 3:00 in the morning most nights for no good reason. That’s when you really hear a house—the tick of the clock, the settling timbers, distant trucks on the highway, and sometimes the forest breathing outside.

One evening before sunset, I took my wife’s old woven basket off its nail. I filled it with apples and huckleberries. I walked to the edge of my yard where the grass gave way to ferns and salal. The woods beyond were already darker, that soft blue-green you get at dusk. I set the basket down on a flat stump just inside the treeline. “There,” I muttered, feeling stupid. If some Bigfoot is out here stealing things, let’s see how polite he is.

I went back inside, left the porch light on, and sat at the kitchen table. The refrigerator hummed, then cycled off, leaving the house very still. Around ten, I turned off the TV. Rain started soft, ticking on the windows. Then from the trees, I heard it. Knock. Pause. Knock. Longer. Pause. Knock. Each one deeper than you’d expect from wood, like it was coming through the ground, too.

I got up, walked to the window, heart up in my throat. I didn’t see anything but the edge of the light and the black beyond it. I told myself raccoons got the apples. I told myself the knocks were just branches in the wind. But the next morning, the basket was gone. No apples, no berries, just a faint lingering smell of wet fur and river mud and three small stones stacked on that stump where the basket had been. I still don’t know who took that basket without leaving a single footprint.

Late September again, almost a year since Tyler disappeared. Same soft rain, same gray sky. By then, I kept the porch light on longer. Sleep wasn’t coming easy. I’d wake and listen for knocks that sometimes came, sometimes didn’t.

One morning, just after dawn, I opened the front door to grab firewood. The air smelled like wet cedar and something else—stronger than before. Like a dog that’s been in the river then rolled in leaves. On the porch post, just beside the steps, was a smear—dark, muddy, with the clear impression of a palm and four fingers, spaced wider than mine by half again. It was high, higher than I could reach without stretching. The woven basket sat on the top step, empty, upright, like someone had placed it there carefully.

Earl came by an hour later. “Damn, Frank. That’s one big hand. Maybe your Bigfoot secret admirer stopped by.” I didn’t joke back. Could have been a prank, I said. Kids messing around or a hunter with big gloves. Earl shook his head. “You in your Bigfoot denial. You’re the one who lives out here alone, not me.”

After he left, I washed the mud off with a rag, hands shaking. I told myself I should call the sheriff, report trespassing. But what was I going to say? Hey, I think a Bigfoot leaned on my porch last night.

By November, I’d gone four nights in a row without real sleep. That’s when you start hearing things that might not be there. Mid November. First real cold snap. Frost on the windows, breath inside the house if you let the fire die down. The stove ticked and popped, and every sound felt like it meant something.

I sat at the kitchen table with an old flip phone in front of me. I kept opening the camera, closing it, telling myself I was being ridiculous. The forest outside was black. No moon, just the porch light’s amber halo on wet gravel. And beyond that, nothing.

About two in the morning, the refrigerator cycled off and the silence came down like a blanket. Then from beyond the treeline, a low rising whoop. Not an owl, not a coyote. It started deep, climbed, then cut off sharp. Then three knocks, closer than they’d ever sounded. I stood up so fast the chair scraped the floor. My heart hammered in my ears. I grabbed the phone and a flashlight, hands sweaty on the metal.

At the door, I hesitated. Every search and rescue briefing, every cop show in my head screamed, “Stay inside.” But another part of me, tired, curious, weirdly guilty, pushed back. I’d spent decades walking into danger for strangers. Now something was at my own doorstep.

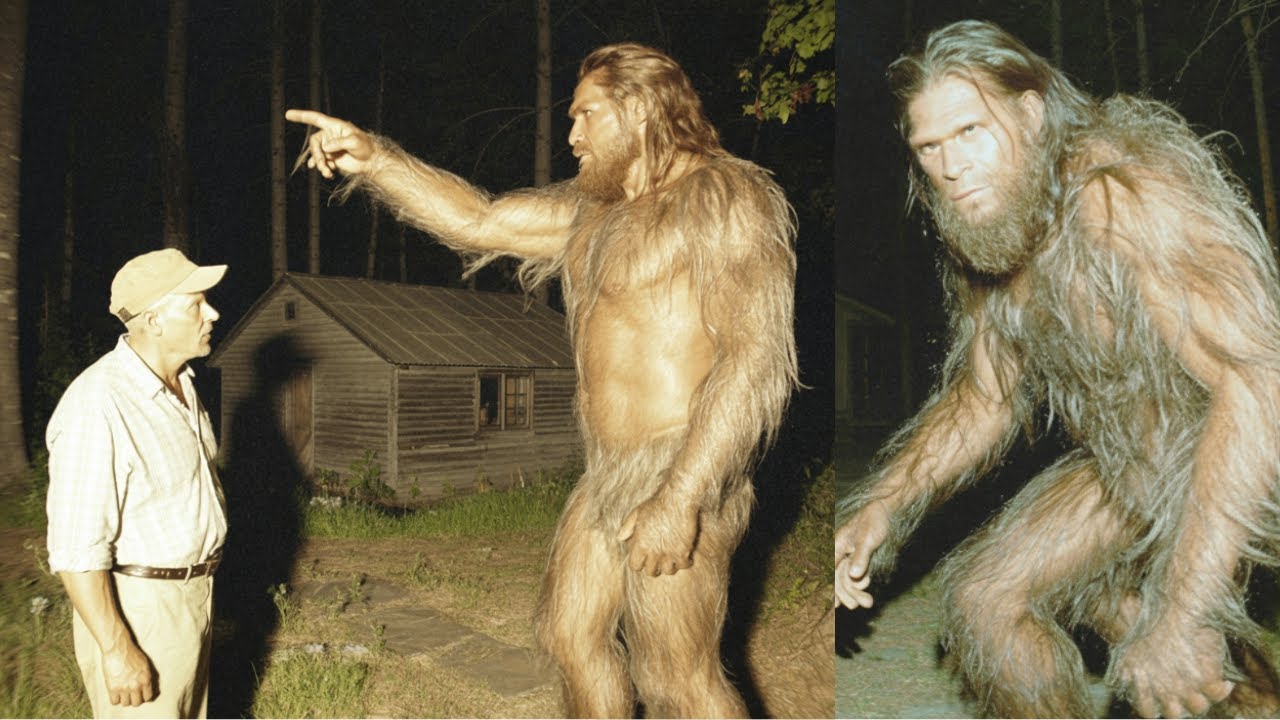

I opened the door. Cold air rushed in, smelling of wet leaves and that same musky fur scent, strong enough to make my eyes water. The porch light hummed. At the edge of the light, between me and the dark trees, was a shape—tall, wider in the shoulders than any man I’d ever seen. Not clear, never TV clear, just a vertical shadow heavier than the night around it. It didn’t move toward me, just stood there. I could hear it breathing. Slow, like someone who’d been crying and hadn’t quite calmed down.

“Bigfoot,” I whispered before I could stop myself. “You’re a Bigfoot, aren’t you?” The word felt like crossing a line. The shape shifted, almost flinched, like it recognized the sound and didn’t like it. Then one long arm lifted slowly and pointed past my house upslope toward the deeper woods in the old volcanic gullies.

I raised the phone, thumb fumbling on the record button. The little red light came on. The shadow turned, took two slow, heavy steps. The boards of my porch railing creaked even though it hadn’t touched them. Then it paused, looked back. At least it felt like it looked back and motioned with that long arm again. An invitation, or a warning. I still don’t know why I followed.

I grabbed my jacket and boots, bare feet inside. The cold bit right through. I left the porch light on behind me. The tall shape was already at the treeline, just beyond where the basket had sat months before. I could smell it stronger out here—wet fur, earth, and something old, like damp stone. The forest was oddly quiet, no crickets, no owls, just the distant rush of a creek and my own breathing.

I kept the flashlight low, sweeping the ground. Each of its steps sank deeper into the soft soil than mine did. I didn’t see its feet clearly, just impressions forming and filling with water as we went. Every so often, it would stop, turn its head in a way I felt more than saw, and wait until I caught up. Then it would move again, always upslope toward a part of the forest I usually avoided—too many washouts, unstable ground.

After maybe an hour, we came to a cut in the land—a steep-sided ravine I’d seen on maps, never in person. The air coming out of it was colder, carrying a smell like wet metal and mildew. The big shape stopped at the edge, one hand resting on a tree trunk. It knocked against it three times. The same slow rhythm I’d heard from my bed. Knock, knock, knock. The sound rolled down into the ravine and came back thinner.

It stepped aside, leaving the path open. My hand shook so hard the flashlight beam jittered across moss and rock. I still don’t know why it trusted me enough to show me what was down there.

The beam of my flashlight cut a narrow tunnel into the ravine. The walls slick with moss, water dripping somewhere, a steady tap that echoed. The smell hit me like a wall—old sweat, mildew, wet canvas, and that musky fur. At the bottom, the ground leveled out into a wide, shallow basin, sheltered by overhanging rock. That’s where I saw them. Backpacks. Dozens at first, then hundreds, piled, stacked, arranged in rows like someone had tried to make order out of chaos. Faded colors, torn straps, buckles catching the flashlight glare like tiny eyes. Sleeping bags, boots, water bottles, woven among them. Things I recognized from certain files—a red bandana, a yellow enamel mug, a carved walking stick.

My throat closed up. I could hear my own pulse in my ears. I panned the light slowly. It just kept going. Gear from the 70s, 80s, newer stuff from the 2000s. A timeline of people who walked into these woods and never walked out. No bones, no bodies, just the shed skins of their lives collected and stored.

Up above, the big shape shifted its weight, rock crumbling softly. I glanced up. “Why?” I whispered. “Why are you showing me this, Bigfoot?” The name felt different now, less like a joke, more like saying Frank or Tyler or Earl. Personal.

No answer, not in any language. But there was something in the way it huddled closer to the tree—like shame or grief.

I raised the flip phone, hit record. The cheap camera whined, trying to focus in the dark. The screen showed mostly black, a few ghost-pale shapes where the light hit the nearest packs. My hand shook. The video blurred. I took maybe twenty seconds of footage before my stomach rebelled and I snapped it shut. Some part of me screamed that I was trespassing on a grave. Even if I couldn’t see the bodies, the air felt thick, heavy with all the last breaths that might have been taken nearby.

Above, the big shape made that low, warbling whoop again—softer this time. Lament, not threat. I stood there until my legs started to shake for more than fear. Then I climbed back up. At the top, the outline turned and walked me back the way we’d come, never touching, never rushing. I still don’t know if it was asking for forgiveness or giving me a warning.

A week later, late November 2005, I sat in the sheriff’s office again. Sheriff Daniels sat across from me, a stack of missing person files between us. “Frank, you’ve been doing this longer than anyone. You think we’re missing something? Some cave? Some old mine?” My mouth went dry. In my head, I saw rows of packs again. “There are a lot of cuts and ravines up there,” I said carefully. “You could hide a town in some of those gullies and no one would know. People get lost. Hypothermia, falls. We just can’t always find them.”

He sighed. “Families want answers. Some of them are talking lawsuits, cover-ups. One woman told me she thinks we’ve got a serial killer living in the woods.” A serial killer would have been easier to explain than a sorrowful Bigfoot curating a museum of the lost.

“You ever give any thought to that old Bigfoot talk?” Daniels asked. “You see a Bigfoot, you tell me, right?” My hand went to the phone in my pocket. I swallowed. “I haven’t seen anything I can put in a report,” I said. “Just tracks that don’t make sense. Gear where it shouldn’t be.” So that’s a no on Bigfoot, he pressed. “I don’t know what I’ve seen,” I said finally. “But if there is a Bigfoot out there, I don’t think it’s hunting for sport.” That was as close to the truth as I could get without sounding insane.

That night, back home, the house felt tighter than ever. I checked the door lock, then checked it again. The refrigerator hummed, then clicked off. In the silence, my hand tapped the table three times without meaning to. Knock. Knock. Knock. I froze, listening for an answer from the woods. None came.

Years went by. Search calls slowed down as my knees gave out. By 2015, I’d retired for good, moved closer into town. Smaller yard, neighbors within shouting distance. Different kind of forest. I brought the flip phone with me. Didn’t use it anymore. But I couldn’t bring myself to throw it away. It lives in my kitchen drawer with rubber bands and old keys. Battery taken out, but still somehow charged with that night.

Sometimes, when the insomnia gets bad and the house is too quiet, fridge humming, clock ticking, I take it out, snap the battery in, and power it up. There’s a single video file in there. Twenty seconds, not ten like I remembered. Memory is funny that way. If you play it, you mostly get black. A few frames show a messy pile of dark shapes—packs. I know they’re packs, but the camera’s too cheap and the light too weak for anyone else to be sure. At the edge of one frame, if you pause just right, there’s a suggestion of a tall shape at the top of a slope. That’s it. No smoking gun, no museum exhibit, just enough to haunt a man, not enough to prove anything to anyone who doesn’t already believe.

A couple of times I thought about posting it online. Anonymous, disturbing footage, that kind of thing. But every time I pictured hunters with high-powered rifles combing the ravines, I pictured families grabbing onto this one blurry video as hope or as a target for their anger. Show them where he is. Make them look. Make them dig. Then I’d remember the way that creature turned back, the way its shoulders slumped like someone carrying everyone else’s secrets.

So I keep the phone in the drawer. Evidence that’s not evidence. Sometimes late, I open the drawer and just hold it. The plastic is cool, a little sticky with age. I still don’t know if keeping that clip hidden is an act of mercy or cowardice.

Now, it’s November 2025. Different house, same rain. You can hear it on the roof, steady as breathing. The lamps in here are soft yellow. I like it dim. Reminds me of the cabin if I don’t think too hard. I’m older. Hands shake a little when I hold my coffee. Nights are long and I still wake up at 3:00 in the morning more than I’d like.

People still disappear in the Cascades. Not as many as the rumor mill says, but enough. Every time I hear about another missing hiker on the news, that old smell comes back in my nose—wet fur, moss, river mud, old canvas. I see rows of packs under rock. I see that tall shadow pointing. Sometimes I catch myself saying the word out loud softly, like I’m talking to a person. Bigfoot. I’ll mutter into my mug. You still up there watching over all that?

The word has changed for me. It’s not a joke or a campfire story anymore. It’s a name. One I use the way you’d say the name of someone you can’t quite forgive and can’t quite blame.

I haven’t been back to that ravine. My legs wouldn’t make it now, even if my mind let me. I’ve told no one the exact spot. The forest can keep that secret.

Last week, during one of those three in the morning wakeups, I shuffled to the kitchen for water. The refrigerator had just cycled off. The house was holding its breath. From somewhere far off, not next door, not across the street, but far beyond that, I heard it. Knock. Pause. Knock. Longer. Pause. Knock. Soft. Almost swallowed by the rain. But there.

I stood at the window, looking at my tiny patch of lawn and the dark line of hills beyond the town lights. I knew in the way you sometimes just know things that those knocks weren’t for me alone. They were just continuing, part of the rhythm of that place, that life up there without us.

I still don’t know exactly what that creature wanted from me that night in 2005—confession, witness, maybe both. But I know this: when folks laugh and say Bigfoot like it’s a punchline, I keep my mouth shut. I let them laugh. Then I go home, sit in the half dark with the fridge humming and the rain ticking on the glass. And I listen for three knocks that might never come again.

And whether you believe me or not, I can still hear them.