Cavers Broke Into a Chamber With a Hibernating Bigfoot — The Footage Is Still Classified – Story

THE YELLOW EYES BENEATH APPALACHIA

A cave confession in six chapters

Chapter 1 — The Pact We Swore in Dirt and Breath

I haven’t slept right in three years. Not since that October weekend in the Appalachian Mountains when my best friend and I climbed into a hole that didn’t belong to us. He never came back out. I did. And every person who’s tried to help me—cops, rangers, therapists, even my wife—eventually arrives at the same comfortable conclusion: grief broke my mind, stress scrambled my memory, and I invented a monster because the truth was too plain to carry.

.

.

.

The problem is I don’t need a monster to explain why he’s gone. I need a monster because I saw it. Because I heard it breathe in the dark with lungs that sounded like bellows. Because I watched yellowish eyes open in the beam of my headlamp and go from sleep to awareness like flipping a switch.

Every night when I close my eyes, I’m back in that chamber with dust on my tongue and fear tightening around my ribs. I hear his voice, the way he tried to keep it steady. I hear the moment it changed—one scream, then silence, the kind of silence that doesn’t mean “quiet” so much as “done.” And every night I make the same choice again. I run. I leave him behind. I save myself and let him die.

The therapist tells me it wasn’t my fault, that I couldn’t have carried him out, that panic does what it does. She wasn’t there for the pact, though. She wasn’t there when two idiots in their twenties, filthy from a crawlspace and laughing with adrenaline, shook hands over a half-crushed sandwich and made a rule that felt like law: always go together, never leave the other behind. If one got stuck, the other dug. If one got hurt, the other carried.

We weren’t professionals. We were worse. We were enthusiasts with enough experience to feel confident and not enough humility to be safe. We started with tourist caves—paved walkways, rehearsed jokes about stalactites and stalagmites—then stared too long at the gated-off passages marked AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY. The sanitized version bored us. We wanted the dark parts that didn’t come with handrails.

For seven years we fed that appetite. The tighter the squeeze, the better. The more remote, the more exciting. Our families called us reckless and they were right. Still, we learned the basics: backup lights, rope work, leaving a plan, respecting the cave the way you respect the ocean. We told ourselves we were careful because we had gear and habits. We told ourselves we were smart because we’d been lucky.

Luck is the most dangerous instructor. It teaches you the wrong lesson until the day it stops teaching at all.

Chapter 2 — The Hole Behind the Rockfall

Late October is perfect for caving—cold enough that you don’t overheat in tight passages, warm enough that your fingers still work. We heard about the entrance from a guy in a gear shop who kept his voice low, like the cave could hear him through the walls. He gave rough coordinates, admitted he’d only been there once years ago, then looked at us with an expression I didn’t understand until later.

“It didn’t feel right,” he said. He didn’t elaborate. When we pressed, he just shook his head, like describing it would invite it closer.

That should have been enough. But he’d dangled the word that always hooked us: unmapped. Or barely mapped. Remote, hidden, the kind of place people didn’t casually stumble into. That’s what we lived for—being the first, or at least being among the few. We spent the week checking gear with obsessive care: fresh batteries, extra lights, rope, food, water. We told our families it was a weekend trip. Back Sunday night. Normal.

We left before sunrise Saturday, drove three hours into narrowing mountain roads, parked at a dead-end logging cut, and hiked. The trail was barely a trail—more suggestion than path. Leaves crunched under boots. The air smelled like pine and damp earth, the first bite of winter waiting in the shadows. Deer tracks crossed our route. Birds called overhead. It felt peaceful in the way a trap often does before it springs.

Finding the entrance took a full hour of searching the rocky hillside. No markings. No footpath. No sign anyone had been there recently. We split up and called to each other, chasing false openings and dead-end cracks until he shouted that he’d found it.

The “entrance” wasn’t an entrance in the way people imagine caves. It was a wound in the hillside, hidden behind a rockfall and old growth, vines and moss camouflaging it until you were close enough to touch. We moved stones together, grunting with effort, and when the last one shifted, darkness exhaled cool air into our faces.

The opening was two feet wide at best, angling sharply down. We checked helmets, lights, packs. He grinned like a kid at the edge of a roller coaster. “Ready?” he asked. I grinned back because that’s what I always did, even when my gut was uneasy.

He went first. He always did. I watched his boots disappear into the rock, heard him call back that it opened up a bit beyond the squeeze, then I slid in after him on my stomach. The mountain closed around me. Temperature dropped. Limestone pressed against my shoulders and helmet. That familiar rush of excitement rose—fear transmuted into thrill, as if danger was just another kind of entertainment.

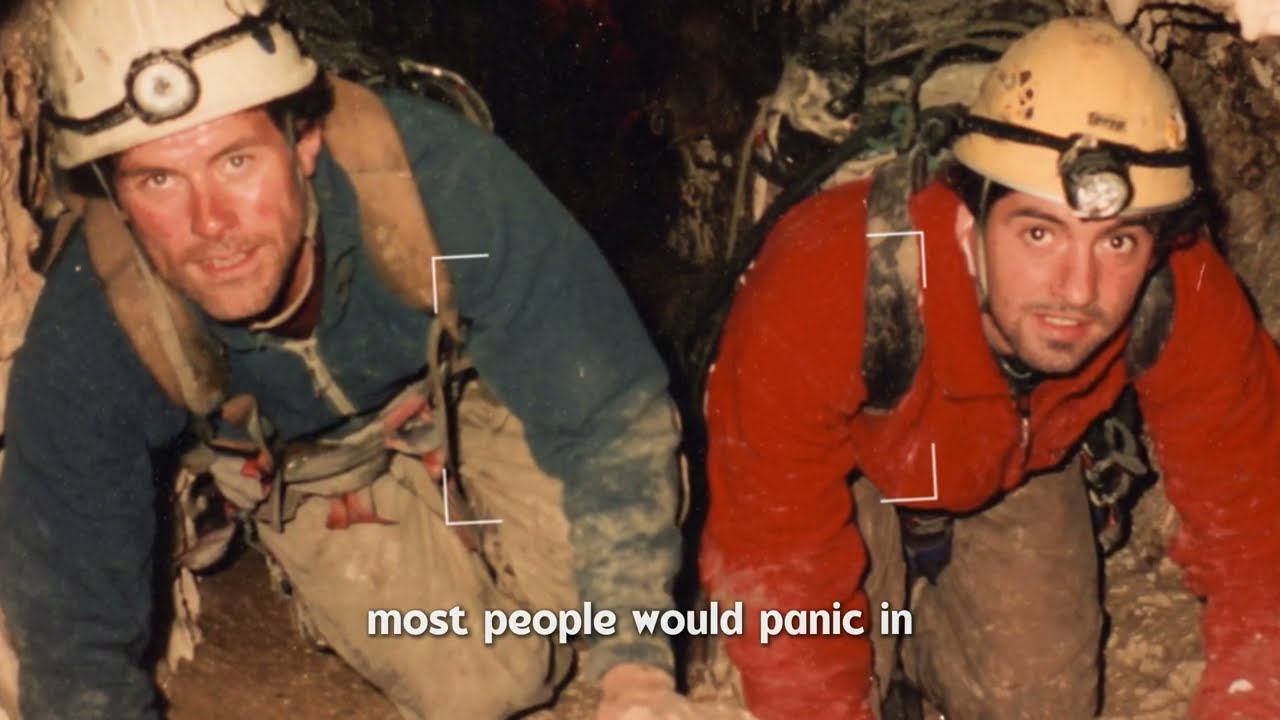

We army-crawled for twenty minutes through passages barely high enough to breathe. The rock scraped my elbows raw. My knees protested. Our headlamps carved thin tunnels of light in a darkness that felt solid. Most people would have panicked. We called it fun.

Eventually the passage widened enough to crouch, then stand hunched. Moisture glittered on limestone walls. Water echoed deeper in. We descended a gentle slope, admiring formations that looked like frozen waterfalls, pillars of calcite rising and meeting overhead.

About an hour in, we found the vertical shaft: a hole in the floor, four feet across, dropping into blackness. We tossed a rock and counted until the splash—fifteen feet, maybe more. We rigged rope. I went first, rappelling into nothing, and landed ankle-deep in icy water. He followed, and we stood in a larger passage where a clear stream ran like a thin vein through the stone.

The cave branched: left followed water upward; right angled down. We didn’t hesitate. We always went deeper. We walked away from safety as if it was the point.

Chapter 3 — Scratches Where Water Doesn’t Go

The air changed as we descended. It wasn’t the usual mineral-cool cave smell anymore. Something organic threaded through it—musk, damp fur, the faint sour note of old blood. We commented on it, laughed it off, blamed fungus or a dead animal. Caves smell weird, we said, because we needed an explanation that didn’t require fear.

Then we noticed the marks. At first they were easy to dismiss as erosion: grooves in limestone where time and water had done their patient work. But the deeper we went, the more deliberate the gouges became—vertical, parallel, recent enough to still look sharp. They didn’t follow waterlines. They climbed too high.

My friend ran his fingers along one set, then pulled back like the stone had bitten him. “These are… wrong,” he whispered. “Too regular.”

“A bear?” I offered, because “bear” is the word you use when you don’t want to say the other word. But even as I said it, I knew. Bears don’t leave marks that high. Bears leave claw traces that tell a different story.

We kept going anyway. We were experts at stepping past warning signs. We called it bravery. It was just stubbornness wearing a heroic mask.

The temperature grew strangely comfortable, warmer than expected, as if the mountain had a pulse. Our voices echoed differently—larger spaces ahead, bigger chambers. We quickened our pace, excited by the promise of something spectacular.

Then we found droppings in the passage—large piles, too big for anything we could name without hesitation. Wrong texture, wrong shape. We stood over them in the glow of our headlamps, both of us thinking the same thought and refusing to speak it. Turning back would mean admitting we were scared. We didn’t do that. We stepped around the piles and continued because we were more afraid of embarrassment than danger.

Soon we started hearing sounds—faint at first, patterning through the rock like a heartbeat. We told ourselves it was water, wind, settling stone. But when we stopped and held perfectly still, it didn’t sound random. It sounded like breathing, deep and slow, distorted by distance and echo.

“We’ve come this far,” my friend murmured. “Might as well see what’s ahead.”

And I agreed, because saying no would have made me the one who broke the momentum. The coward. The quitter. I followed him deeper, while the primitive part of my brain screamed that this wasn’t curiosity anymore. This was trespassing.

Chapter 4 — The Chamber That Shouldn’t Exist

The passage opened abruptly into a chamber so large our headlamps couldn’t reach the ceiling or far walls. Darkness stretched outward in every direction, swallowing the beam edges like ink. We stood at the threshold, stunned, then my friend threw a rock into the void. Four seconds passed before it clattered somewhere far away. The chamber was enormous—bigger than anything we’d ever seen. We whooped like kids. Our excitement echoed back from multiple directions, thin and warped, as if the cave itself didn’t like being disturbed.

Then we noticed the glow. Faint light, not bright like an exit nearby, but a distant pallor ahead—as if daylight filtered through an opening far above. Another entrance, we thought. Multiple exits. Safer. Bigger system. Good news.

And then we saw the footprints in the dust. Lots of them. Large prints, bipedal, too wide, too long, toes arranged almost like a human’s but not quite. No claw marks. Stride length too long for a bear. The pattern was wrong for any animal we could name without lying.

We should have left then. The cave had given us every warning it could without speaking. But the chamber seduced us with its scale. We walked carefully, voices lowered without admitting why, following tracks and examining deep gouges on the walls—scratches six feet long, fresh and angry, carved into limestone by something tall and powerful.

Then we found what looked like a nest against one wall: leaves, branches, moss—materials dragged down from the surface, layered old and fresh. Bones were scattered around it. Deer bones, many of them. Some still held dried scraps of flesh and fur. Recent kills.

That was the moment the thrill died and turned into a different kind of energy, electric and sour. We weren’t explorers anymore. We were intruders standing in a feeding place.

We sat against a boulder to eat, because it’s amazing what denial can do. We told ourselves food would steady our nerves, that rest would make us think clearly. The chamber around us felt wrong in its silence—no drip, no wind, just the quiet echo of our own breath.

Then we heard it clearly: deep rhythmic breathing coming from a darker alcove off to the side. Not our breathing. This was slow, powerful, resonant, like air being pulled through a giant chest. The sound carried the texture of sleep—regular, unhurried, confident.

We froze with energy bars halfway to our mouths.

My friend’s eyes lit up, not with fear but with awe. “We have to see it,” he whispered. “Whatever it is, this is… this is huge. We have to document it.”

Every instinct in me begged to back away, to leave without looking, to choose life over curiosity. But I couldn’t let him go alone. The pact sat heavy in my head. So when he stood and moved toward the breathing, I followed—hands shaking, stomach knotting, heart hammering like it was trying to escape my ribs first.

We dimmed our lamps and crept forward, stepping around loose rocks. The breathing grew louder. We rounded a boulder, and there it was—curled on the cave floor, sleeping.

At first my mind tried the last lie it had left. Bear. It has to be a bear. But it wasn’t. The proportions were wrong. Arms too long. Torso too massive. Hair thick and dark reddish-brown covering it like a cloak. Even asleep, it looked built for power rather than peace.

We edged closer. Twenty feet. Close enough to see a chest rising and falling with each breath, hands bigger than plates, thick nails that looked almost like claws. The face was turned partly away, but I could see the profile: heavy brow ridge, flat nose, jaw too strong, too broad. Not human. Not ape. Something in between that made my skin prickle as if my body recognized a predator before my mind did.

Then the smell hit: musky, pungent, animal but not like any animal I’d encountered. Sweat, old blood, the damp metallic stench of something that lived under stone and ate in darkness. My eyes watered. My stomach turned.

My friend motioned to get closer for a better angle. He wanted the face. He wanted proof.

And then he stepped on loose rocks.

Chapter 5 — The Moment Its Eyes Opened

The stones shifted with a small sound—barely anything, but in that chamber it echoed like a whisper into a sleeping ear. The breathing pattern changed. Stuttered. Stopped.

We froze. I felt the blood drain from my hands. Nothing happened for a heartbeat, then another. For a second I thought we might still get away.

Then my friend made the second mistake—the one that broke the fragile line between us and it. He aimed his helmet light directly at its face and turned it to full brightness.

The creature’s eyes opened. Yellowish, huge, pupils contracting against the sudden glare. There was no slow waking, no confusion, no grogginess. It went from asleep to alert instantly, like a predator that never truly rests. A low rumble vibrated out of its chest and into the rock beneath our feet.

It began to sit up. And as it unfolded, it became even more wrong—eight feet tall at least, shoulders broad enough to make a man look like a child, muscles shifting beneath hair with terrifying smoothness. Its face was fully visible now: heavy brow ridge, wide mouth, flattened nose, features that could almost be human if they weren’t arranged with such brutal otherness.

For a fraction of a second it looked confused—then it focused on us, and something sharpened in its expression. Not just anger. Not just fear. Possession. The look of a thing in its den deciding what to do with trespassers.

My friend yelled something—I don’t remember the word. It doesn’t matter. The sound that followed mattered more: a roar that shook dust from the ceiling and sent small rocks clattering around us. The creature rose and we ran, headlamps bouncing wildly, shadows leaping across cave walls like grasping hands.

Behind us, heavy footfalls hit stone in fast rhythm. It could move. It moved faster than something that size had any right to move. The sound of pursuit wasn’t just chasing—it was hunting.

We split instinctively around a rock formation, no plan, no signal. I went left. He went right. I looked back once and saw the silhouette against the faint distant glow, head turning between us, deciding which prey to follow first.

Then I ducked behind a cluster of stalagmites and did something I still hate myself for: I turned off my helmet light. I plunged myself into total darkness and pressed my back to cold stone, one hand over my mouth to quiet my breath.

I listened.

I could hear my friend’s light bobbing in the distance, hear his footsteps and panicked breathing, hear the creature’s pursuit moving away from me—heavy footfalls, faster now, excited. The sounds of hunting faded deeper into the cave, leaving me in a pocket of silence that felt like cowardice made physical.

Time warped. Minutes stretched into something that felt like hours. When I finally dared to turn my light back on, the chamber looked different—no longer majestic, only hostile. Every shadow felt occupied.

I whispered his name. No response. I whispered again. Then, faint and far, a voice: “Hey—over here.”

Relief flooded me so hard my legs trembled. I found him behind a boulder, bleeding from a scrape on his forehead, eyes blinking against blood. He said he was okay. I wanted to believe him so badly it hurt.

We tried to find our way back, but panic had scrambled our sense of direction. The chamber had multiple openings. The breathing echoed from somewhere we couldn’t locate, acoustics bending sound until it felt like it came from everywhere.

We chose a passage and moved quietly. Fifty feet in, we heard movement ahead. Heavy breathing.

It had circled around.

We saw its eyes first—those huge yellowish reflections in the dark. It stood in the passage like a door closing. It didn’t charge. It walked toward us slowly, steady, purposeful, as if it knew it had time.

We backed up, keeping lights on it, hoping brightness would scare it. It kept coming. Step by step, it herded us back into the chamber, then stopped at the passage mouth and waited, blocking the route as calmly as a wolf blocking a trail.

That’s when we understood the worst truth: it knew the cave. We didn’t. It could keep us here as long as it wanted.

Chapter 6 — The Choice I’ll Never Outrun

We huddled in a shallow alcove, pressed close to stone, whispering through panic. Trapped. Outmatched. The pact between us felt like a rope tightening. We couldn’t fight it. We couldn’t outrun it in open space. If it decided to come into our alcove, the story would end there.

My friend proposed the plan that destroyed my life: split up again. One runs loud and obvious, draws it away. The other waits and bolts for the exit when it follows.

I refused. I tried to refuse. I said we’d find another way, that we’d stick together, that our pact mattered. But he insisted. One of us had to get out. One of us had to tell people what was down here. He said he’d be the decoy. He said he could lose it in the passages. He said we’d meet at the entrance.

We argued in whispers until the cave’s silence felt like a threat. In the end, I agreed because I ran out of courage and because he was already moving like someone who’d decided. He hugged me hard, quick, and whispered, “See you on the surface.”

Then he sprinted across the chamber, yelling to get its attention. His light bounced like a beacon. Immediately the creature moved—heavy footfalls launching after him, roar echoing into the cave’s vast throat. I waited seconds that felt like betrayal, then I ran for the passage we thought led back.

I ran harder than I ever have in my life. I found the rope. I climbed, hands slipping on wet fibers, lungs burning. In the chamber below, I heard movement I couldn’t place. I didn’t look down. I didn’t stop.

I reached the crawlspace and shoved myself into it, scraping along limestone, pushing my pack ahead. Behind me, something followed—massive movement trying to enter the narrow passage, rock groaning under pressure, stones falling around me. The creature roared in frustration, claws scraping stone as it tried to widen the opening, but the mountain held. It couldn’t fit.

I crawled until my arms and legs felt shredded, until the passage seemed endless, until I saw daylight ahead like salvation. I spilled out onto the hillside, gasping, collapsing into cold air. The sun was setting. We’d lost the whole day under rock.

I waited. I called his name until my throat broke. An hour passed. Two. Night fell. Stars came out, indifferent. He never appeared.

I hiked back to my truck in darkness and shock, drove to the ranger station, pounded on the door, begged for help. A rescue team came at dawn, went in as far as they safely could, then refused to risk more lives in a passage too narrow and unstable. They searched for other entrances. Dogs, helicopters, radar. They found nothing that matched the chamber I described.

Soon the story shifted. They suggested collapse. Disorientation. Trauma. They used the word “hallucination” with the gentleness you reserve for the wounded. They looked at me like they were already writing the version they could live with.

Two weeks later, the search was called off. He was declared dead, body unrecovered. Official reports said we entered an unstable system and he was likely buried in a collapse. They handed me a pamphlet about grief counseling like it was closure.

I attended the memorial and couldn’t speak. His girlfriend looked at me like she was waiting for an explanation I couldn’t give. When I tried, even once, to tell anyone about the thing down there, the look in their eyes changed—concern replacing belief. So I stopped. I let them have their clean narrative.

But at night, clean narratives don’t help. At night, I smell the musk again. I see the eyes. I hear the breathing. I hear the scream cut short. And I feel the weight of the pact we made in dirt and breath, the one rule we thought made us invincible.

The last text he sent me—before we reached that chamber—still lives on my phone. Three words that feel like a curse: This is going to be epic.

He was right. It was epic. Just not in the way he meant.

And somewhere under those mountains, in a chamber that doesn’t appear on maps and doesn’t exist in official reports, something still breathes in the dark. Waiting. Listening. Patient in the way predators are patient.

I don’t go caving anymore. I don’t even hike that ridge. I sit in my truck at the trailhead sometimes and stare at the mountains like they’re a locked door. People think time will soften this. They don’t understand: time doesn’t soften a choice you relive every night. It sharpens it.

Because I lived.

And he didn’t.