“Close Your Eyes” — What German POW Children Were Told Before American Doctors Arrived

Eyes Open at Camp Swift (Texas, Summer 1945)

Chapter 1 — “Close Your Eyes. Don’t Scream.”

Texas heat had a way of making fear feel physical. In June of 1945 the war in Europe was over, radios said so, newspapers shouted it, and yet inside the wooden barracks of Camp Swift the end of the fighting did not mean the end of dread. The compound lay in central Texas amid cedar and limestone hills, a wide sky stretched over everything like a hard blue lid. Dust hung in the air where sunlight slanted through the windows, and the smell was a mix of pine, sweat, and the sharp tang of worry.

.

.

.

In Barracks 14, thirty-two families waited. Not soldiers—women and children, civilians who had been swept into detention when merchant ships were seized early in the war. They had learned to measure time by routines: meal lines, roll calls, the rare visits from husbands and fathers held elsewhere in the camp, the slow shift of seasons that felt wrong under a foreign sun. That afternoon, they were waiting for an American doctor.

Greta held her five-year-old daughter Lisel’s hand so tightly the small fingers blanched. Around them, mothers whispered in German, passing the same instruction from woman to child, grandmother to grandson, as if the words themselves could form armor: “Close your eyes. Don’t scream. No matter what they do.”

Propaganda had planted the fear carefully. German papers—some smuggled, some remembered, some repeated until they became truth—had warned that enemy doctors performed experiments, sterilized prisoners, injected diseases. Photographs had circulated, whether genuine or manufactured no longer mattered; fear doesn’t need proof when it has repetition. Over years, that message had sunk deep enough to survive reason. If the doctor was kind, it would be a trick. If he was calm, it would be concealment. If he smiled, it would be because he enjoyed power.

Anna Richter sat on the edge of her bunk with her seven-year-old son Klaus pressed against her hip. Before the war she had been a seamstress in Hamburg. Now she mended uniforms for American officers in exchange for extra rations, her stitches neat because neatness was one thing the war had not stolen from her. Klaus had been four when they were detained. He remembered Germany in fragments—sirens, the sour smell of burning, an older voice singing to keep him quiet. America was his reality now, but it was a reality shaped by whispers.

“Mama,” he asked, softly, his accent oddly mixed, German consonants softened by months of hearing Texas English from guards. “Will it hurt?”

Anna’s throat tightened. She wanted to say no. She wanted to promise him safety the way a mother should. But she had learned that promises could be weapons if they were false. Instead she brushed his hair back and repeated the ritual, because it was all she had to offer: “Close your eyes. Stay very still. I will hold your hand the whole time.”

Outside, footsteps approached on the gravel path. The women went quiet as one organism. A shadow crossed the doorway. An American sergeant stood there, uniform crisp despite the heat, face sunburned, expression controlled.

“Time, ladies,” he said in careful German, the words practiced but sincere. “Doctor is ready. Bring the children.”

The line formed slowly—skirts, small hands, wide eyes. It was the kind of procession people make when they believe punishment is inevitable. And yet it moved, because these women had learned another rule in captivity: resistance often costs more than it gains.

Chapter 2 — The Doctor Who Noticed the Posture

The medical building sat at the eastern edge of the compound, a prefabricated structure that smelled of disinfectant and fresh-cut wood. Inside, the walls were painted a flat institutional white. Examination tables lined the room. Metal trays held stethoscopes, tongue depressors, syringes that caught the fluorescent light with a clean gleam. To the mothers, each instrument looked like a potential weapon—because fear will turn anything into a threat.

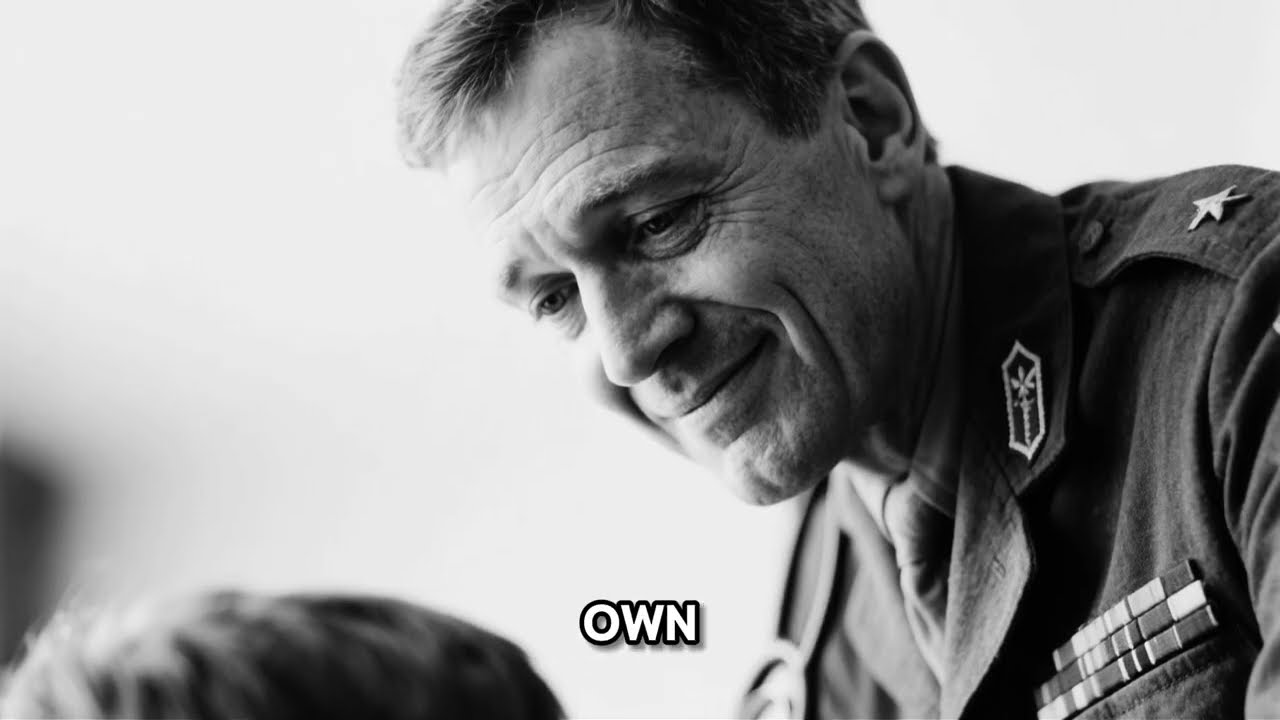

Captain James Morrison waited near the back with a clipboard. He was thirty-eight, a general practitioner from Oregon, assigned to camp medical services after being judged too old for combat duty. He carried a photograph of his wife and daughters in his uniform pocket, the edges worn from being touched when the day was hard. He had treated hundreds of German prisoners at Camp Swift: mostly young men with minor infections, work injuries, stomach trouble, the occasional appendix that needed removing. He had learned to keep his tone steady, his procedures consistent, his temper under control. A camp doctor did not have the luxury of improvising personalities.

The civilians were different. When the women entered with their children, Morrison felt himself pause in a way he didn’t expect. It was their posture. Soldiers approached medical care with reluctant acceptance, sometimes suspicion, but rarely panic. These mothers held their children as if shielding them from execution. The children’s faces carried a tight, practiced terror—an expression Morrison had seen only in photographs from liberated camps overseas, the look of people who expect cruelty because cruelty has been promised.

A German-American corporal named Weber served as translator. He had left Germany with his family years earlier, long before the worst, and there was a quiet heaviness behind his competence. He repeated Morrison’s first instruction in German: one child at a time, routine health checks, nothing painful.

No one moved.

The silence had weight. Morrison could feel it, dense as heat.

Finally Anna stepped forward, because someone always has to go first. Klaus pressed into her side, fingers locked around hers. Anna’s face was composed in the way desperation sometimes looks like dignity.

Morrison softened his voice, the way he did with frightened children back home. “Hello there, young man,” he said, and waited for Weber. “What’s your name?”

Klaus stared at the floor.

“It’s all right,” Morrison continued, carefully. “I’m going to listen to your heart and lungs. Check your throat. Make sure you’re healthy. It won’t hurt.”

As Weber translated, Morrison noticed Anna’s lips moving. She was whispering to Klaus—again and again, a prayer in the wrong place. Weber hesitated, then leaned toward Morrison.

“Sir,” he said quietly, “she’s telling him to close his eyes and not scream.”

The words landed like a blow. Morrison set down the stethoscope. Not because he was offended, but because he understood. The fear in this room wasn’t ordinary suspicion. It was a system built inside people, reinforced for years, designed to make them expect the worst so they would never be surprised by it.

Morrison crouched so his eyes were level with Klaus’s. He spoke slowly, giving Weber time to translate clearly. “You don’t need to close your eyes,” he said. “And you won’t feel anything that would make you scream. You can watch everything I do. Your mother can hold your hand the whole time.”

Anna’s expression remained guarded, but something in it shifted—the smallest crack, the tiniest permission for reality to enter. She gave a slight nod.

Morrison lifted Klaus onto the table with exaggerated gentleness. He showed him the stethoscope, let him touch the cold metal disc, explained what it did. “It’ll feel cold,” he warned, honest even about small discomforts, because honesty was how trust began.

“Deep breath,” he said.

Klaus obeyed, tense as wire. Morrison listened. Clear lungs. Strong heart. No fever. No hidden rattle.

He checked the throat. Ears. Abdomen. Each touch careful, each instrument shown before use. Klaus watched every movement, waiting for the moment when gentleness would turn into harm.

It never did.

“He’s very healthy,” Morrison told Anna through Weber. “Good strong heartbeat. No signs of illness. Fine boy.”

Anna’s eyes filled, and she blinked hard, trying to keep tears inside as if tears were weakness. Klaus slid off the table and buried his face in her skirt, not because he was hurt, but because the fear had nowhere to go.

Morrison made a note and gestured for the next child.

That’s how it began—not with speeches, not with orders, but with one careful examination and one promise kept.

Chapter 3 — The Sound That Broke the Room

The line moved. Mothers still whispered the ritual—close your eyes, don’t scream—but their voices grew less certain with each child who returned unharmed. Morrison worked steadily for hours, never rushing, narrating every action, praising each child for standing still. He treated ringworm with calm practicality. He noted vitamin deficiencies and immediately ordered supplements. He found a heart murmur in one boy, likely congenital, not dangerous today but worth monitoring, and scheduled follow-up visits. Nothing dramatic, nothing heroic in a battlefield sense—just medicine done properly, as if these children were simply children and not symbols of an enemy nation.

By the time Greta and Lisel reached the front, something had changed in the air. Word had traveled in the quiet way news travels among frightened people: the doctor had not hurt anyone. He had smiled. He had spoken gently. He had behaved like a man with daughters of his own.

Lisel climbed onto the table without being lifted, chin raised with the stubborn bravery of a five-year-old trying to copy adults. When Morrison placed the stethoscope on her chest, she startled at the cold and then—unexpectedly—giggled. The sound was bright and small, but it hit the room like a hammer through glass.

That giggle broke a barrier no one had admitted was there. Some mothers exhaled for the first time in what felt like hours. A toddler stopped whining, distracted by the strange idea that a medical exam could be something other than terror. Children whispered to each other, comparing the cold stethoscope, the tongue depressor, the doctor’s calm face.

Morrison kept working. He did not celebrate. He did not act as though he had won. He simply continued, because professionals continue, and because the surest way to prove a promise is to keep it more than once.

When the last child was examined, Morrison addressed the women through Weber. “Your children are mostly healthy,” he said. “That speaks well of how you’ve cared for them in difficult circumstances. The camp pharmacy will provide what the few need. If any child shows signs of illness—fever, cough, anything unusual—you can request medical attention immediately. That is your right under the Geneva Convention.”

The phrase “your right” mattered. It was not a favor. It was a rule. Many American soldiers at the camp carried themselves with that same belief—discipline not as cruelty, but as structure; rules not as weakness, but as the line separating civilized conduct from revenge.

The women filed out slowly. Some offered formal thanks, stiff words in English they had practiced like a lifeline. Others nodded, still stunned.

Anna lingered at the doorway. She turned back to Morrison.

“Thank you,” she said in careful English. “For my son. Thank you.”

Morrison nodded once. “He’s a good boy,” he replied. “Take care of him.”

After the last family left, Weber helped organize records. Morrison sat down heavily, a different kind of exhaustion settling into his bones.

“They really believed we would hurt them,” he said quietly. “Those kids expected torture.”

Weber was silent for a moment. Then he said, as if remembering an older voice: “My grandmother used to say the truth has a different weight than propaganda. You can feel it if you pay attention.”

Morrison stared at the blank wall and understood the scale of what he had seen. Not a medical crisis, not an outbreak, but an entire roomful of human beings trained to fear kindness.

Undoing that would take time.

It would also take consistency.

Chapter 4 — The Needle Test

Camp Swift settled back into its routines. Work details in the morning, meals at prescribed times, mail call in the evening when letters arrived—news from Germany written on thin paper, filled with destruction, hunger, missing relatives. Children attended makeshift classes taught by educated prisoners. They played in dusty recreation yards, inventing games that mixed German habits with American words overheard from guards. Captivity became a strange hybrid existence: not freedom, but not the nightmare they had imagined.

Morrison continued his rounds with the same steady competence. He treated infections, set broken fingers, monitored fevers. Something subtle changed: prisoners began reporting symptoms earlier. They stopped waiting until pain became unbearable. Mothers brought children at the first sign of illness instead of hiding problems out of fear.

Trust, Morrison learned, did not arrive with one good act. It arrived by accumulation.

Then August brought a new test. A polio scare swept through central Texas. Three cases appeared in nearby Austin. Health officials mandated immediate vaccination for all children in the region—including those in POW camps.

Morrison read the directive and felt his stomach tighten. Vaccines meant needles. Examinations were one thing; injections were another. Needles matched the propaganda too neatly. If there was ever a moment for old fears to return, this was it.

He requested additional staff and permission to explain the situation to families beforehand. Camp authorities agreed. A meeting was scheduled in the mess hall. Notices went out in German and English. Attendance mandatory.

That evening more than three hundred prisoners crowded into the dining facility. Families with children sat near the front, rigid with tension. Morrison stood at the head with a microphone. Weber translated beside him.

“I’m here to talk about polio,” Morrison began. “It’s a disease that primarily affects children. It can cause paralysis, permanent disability, even death. To protect your children, we’re going to vaccinate every child in this camp.”

A murmur rippled through the crowd. Morrison raised his hand, steadying the room before fear could catch fire.

“The vaccine requires an injection,” he continued. “A needle. It will hurt for a moment. I won’t lie to you about that. The pain lasts seconds. The protection lasts years. I’ve seen what polio does to children. This prevents that.”

He paused, letting Weber’s German settle into the room.

“I know some of you were taught that American doctors experiment on prisoners,” Morrison said, meeting eyes. “But I need you to think about what you’ve experienced here. Have I or my staff hurt your children? Have we done anything except try to keep them healthy?”

Silence again—different from before. This silence was calculation. The mothers exchanged glances. Anna felt the weight of the question in her chest. It was true: Morrison had treated Klaus’s ear infection. He had given vitamins. He had kept promises.

“I’m asking you to trust us one more time,” Morrison said. “This disease doesn’t care about nationality. Polio doesn’t distinguish between American and German children. Neither do we.”

The meeting ended without cheers, without applause. It ended the way adult decisions often end: quietly, with people thinking hard.

Morrison waited through the following days with a pressure behind his ribs. Forcing medical treatment violated protections. The decision had to be theirs.

On Wednesday morning Anna appeared at the medical building with Klaus beside her, hand gripping hers.

“We will do the vaccine,” she said in halting English. “Other mothers are coming. But I want to go first so they can see.”

Morrison felt something loosen inside him—relief mixed with respect. “That’s very brave,” he said. Then, because he had learned the value of speaking plainly, “This will hurt. Like a bee sting. Then it’s over.”

Klaus watched him prepare the injection. Morrison explained each step. He did not pretend needles were nothing. He treated Klaus as a person capable of understanding, which was its own form of respect.

When the needle went in, Klaus flinched. His mouth opened as if to scream—then closed. He gripped his mother’s hand and endured the brief sting. Morrison withdrew the needle, applied a small bandage, and—reaching into a jar kept for moments like this—gave Klaus a piece of hard candy.

“All done,” Morrison said warmly. “You’re very courageous.”

Klaus studied the bandage with fascination, as if it were a medal he had earned. Outside the window mothers watched. When Anna and Klaus emerged intact, the decision solidified across the group.

One by one, children came in. Some cried. Some went rigid with fear. Some clenched their teeth in silence. Morrison treated them all with the same patience, the same honesty, the same steady hands. The medical staff moved like a practiced team. By the end of the week every child in the civilian section had been vaccinated.

The clinic was not dramatic. It was not a battle. Yet Morrison wrote his wife that night and tried to explain why it mattered. Not because he wanted praise, but because he wanted someone to understand that mercy could be a kind of victory.

“I think we won something here,” he wrote. “We proved that keeping your word—over and over—can be stronger than fear.”

Chapter 5 — A Small Cake Under a Big Sky

September brought cooler evenings and talk of repatriation. The war in the Pacific ended. Camp Swift faced a new uncertainty: what would happen to prisoners now? They would return to a Germany shattered into rubble, families scattered, cities unrecognizable. For many women, the idea of “home” was no longer comforting. It was a question mark shaped like ruins.

The children, however, carried a different kind of knowledge. They would leave Texas knowing America not as a monster from propaganda, but as a place where guards sometimes shared a joke, where a doctor explained his instruments, where rules were followed even when hatred would have been easier. That did not erase the larger crimes of the regime; nothing could. But it did complicate the simplistic story the regime had used to keep people obedient: the story that all enemies were savages and all Germans were victims. Reality had more texture than that.

Klaus turned eight in October. Anna saved rations to make a small cake—dry and plain, but real. Morrison quietly arranged for eggs and sugar from the commissary. When Klaus blew out makeshift candles twisted from paper, he made a wish he couldn’t have named aloud. Perhaps it was simply this: that the world would stop demanding fear from children.

In November the mass repatriation began. Buses rolled out. Trains carried families east toward ports. Barracks emptied one by one. The camp’s noise changed: less shouting, fewer footsteps, more silence. Morrison watched departures with a familiar ache. He had kept people healthy through captivity only to send them back into chaos.

On a cold December morning—frost on Texas ground like lace—Anna and Klaus were among the last groups to leave. Morrison came to see them off. He crouched to Klaus’s level, his voice gentle in the way it had been from the first day.

“Take care of yourself,” he said. “Listen to your mother. Study hard. Grow up to be a good man.”

Klaus nodded solemnly. Then, with sudden childhood impulse, he stepped forward and hugged Morrison quickly—arms around a stranger who no longer felt like a stranger.

Anna’s eyes filled with tears. This time she did not hide them. “You showed us,” she said in careful English, “that the propaganda was wrong about many things. Thank you.”

Morrison nodded, unable to find a grand response that would not cheapen the moment. The buses took them away down the dusty road toward the railway. He watched until they disappeared and then returned to the medical building, where other patients waited. The work continued; it always did.

That evening, alone in his quarters, Morrison thought about the phrase the mothers had repeated like armor: close your eyes, don’t scream. He thought about how Klaus had kept his eyes open. How Lisel had giggled at cold metal. How an entire room had shifted, not because anyone delivered a speech, but because a doctor and the soldiers around him had insisted on decency as a habit.

Historians would write about battles and treaties. They would count tanks and measure front lines. But Morrison understood something quieter: every child who learned that mercy could cross enemy lines carried that knowledge into the future. Every mother who discovered that propaganda could be dismantled by lived truth would tell her story. It was not redemption. It was not forgiveness. It was simply a fact—and facts, repeated honestly, are stubborn things.

Years later, Klaus would tell his own children about Texas, about a camp that should have been only fear, and about an American doctor who treated a frightened boy as if his life mattered. He would not call it a miracle. He would call it what it was: a promise kept, again and again, until fear had to make room for reality.

And that, in a world that had run on lies, was no small victory.