EX–CIA Agent Got Attacked by a DOGMAN, What Happened Next Will Shock You

The Dogmen Files: Forty Years of Silence

When a decorated CIA field operative is ordered to investigate something that officially doesn’t exist, you know the rabbit hole goes deeper than anyone imagines.

For forty years, I’ve carried classified knowledge about creatures the government has been tracking since the Cold War. Creatures that walk upright like men, but possess the savagery of apex predators.

They call them dogmen. And what I’ve witnessed in the field has kept me silent until now. But silence has a weight. And after four decades, it’s time someone told the truth.

.

.

.

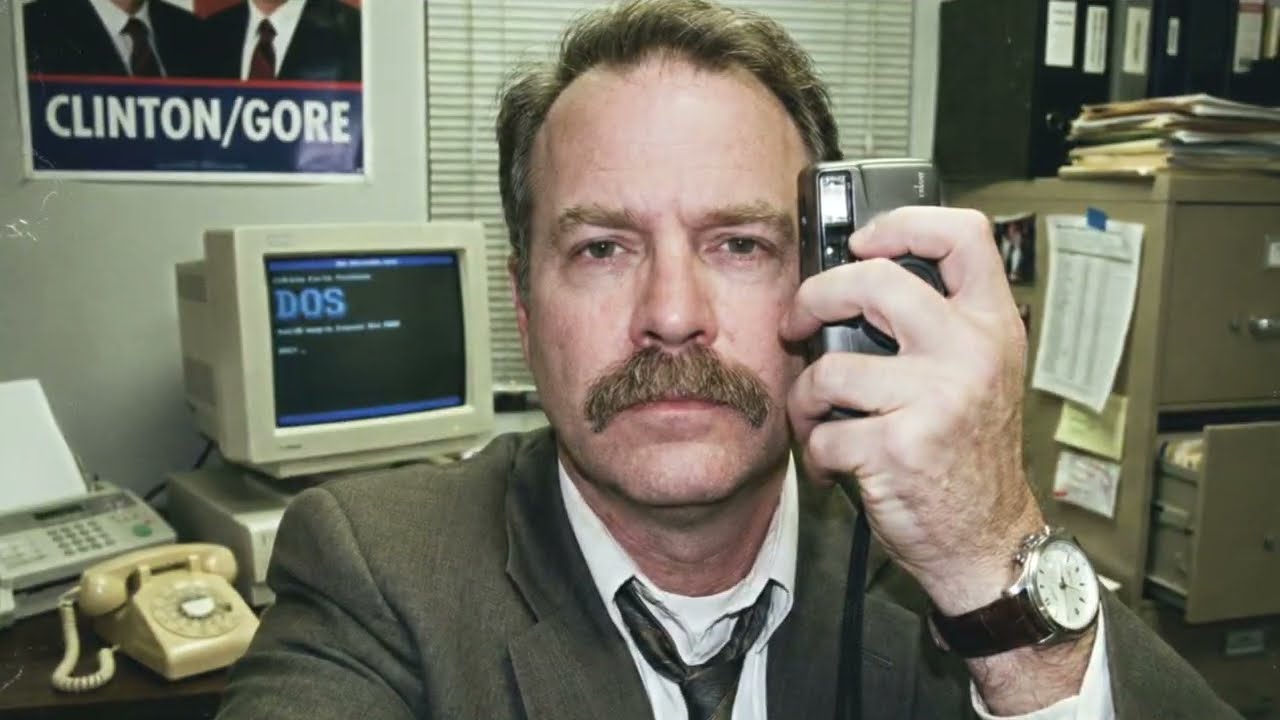

My name is John Penelopey, though that’s not the name I used during my operational years. In March 1987, I was a thirty-two-year-old field operative working for a division of the CIA that most agency personnel didn’t even know existed. Our official designation was the Biological Anomaly Research and Containment Unit—BARCU. Internally, we just called it the Program.

Our mandate was simple on paper, but terrifying in practice: investigate, document, and, when necessary, contain biological entities that fell outside conventional scientific classification.

I had a background that made me valuable to the Program: a master’s in zoology from Cornell, eight years with Army Special Forces, psychological operations training, and a security clearance that went beyond top secret into compartments most generals didn’t know existed. I’d seen combat in places the public would never know about, dealt with every variety of human threat, and thought I understood the full spectrum of danger this world had to offer.

I was wrong.

The call came on a gray Tuesday morning in March. My handler, a woman I knew only as Control, contacted me through the secure line in my Arlington apartment.

“Reeves, pack for two weeks in the field. Cold weather gear. You’re being deployed to northern Wisconsin within six hours.” Her voice was steady, but beneath it, I detected something close to fear. “Local law enforcement found something three days ago. A hunting party—or what’s left of them. Four experienced outdoorsmen, torn apart in the Chequamegon National Forest. The scene is… inconsistent with any known predator behavior. We’ve contained the local investigation, but we need assessment and possible containment protocols activated.”

I’d worked enough of these cases to read between the lines. “Inconsistent with known predator behavior” meant something had killed humans in ways that couldn’t be explained by bears, wolves, or mountain lions. “Containment protocols” meant there was a possibility we were dealing with one of them—the things we tracked, the things that supposedly didn’t exist.

“I’ll be ready in three hours,” I said.

“Two hours,” Control corrected. “The helicopter leaves from Reagan National at 1300. Don’t be late, Marcus. This one feels different.”

Different how? I wanted to ask, but the line was already dead.

The flight took me to a small regional airport outside Park Falls, where I was met by Agent Sarah Chen, a forensic specialist I’d worked with before. Sarah was brilliant, methodical, and one of the few people in the Program who’d seen as much field time as I had without cracking under the psychological weight.

She greeted me with a grim expression and a file folder marked with classification stamps I’d only seen a handful of times. “It’s bad, Marcus,” she said as we climbed into an unmarked SUV. “Worse than anything I’ve processed before.”

We drove forty-five minutes into increasingly remote territory. The forest was dense, the roads barely maintained. Finally, we turned onto a logging road blocked off with orange cones and an unmarked van. Two men in tactical gear, military despite their civilian clothes, waved us through.

A mile deeper, we reached the scene: a temporary command post—tents heated by portable generators. Personnel in unmarked uniforms, all carrying high-caliber rifles, not standard issue. Dr. James Cartwright, the lead forensic pathologist, met us at the command tent. He was in his fifties, gray-haired, with eyes that had seen too much.

“I need to prepare you for what you’re about to see,” he said. “I’ve processed mass casualty events, war crimes, the worst humanity can inflict. This is different.”

“Show me,” I said quietly.

The kill site was another hundred yards into the forest. The first thing that hit me was the smell—even in the cold March air, even after three days, the scent of death and something else, musky and wild, hung heavy.

The second thing I noticed was the trees. Deep gouges in the bark, eight to ten feet off the ground. Four parallel claw marks that had torn through wood like paper. Then I saw the remains.

Dr. Cartwright was right. This was beyond anything I’d encountered. Four adult males, all experienced hunters based on the equipment, had been systematically torn apart. Not eaten, not dragged away—torn apart with focused rage. Limbs separated from torsos with force that suggested strength far beyond any known animal. Claw marks matched the ones on the trees. Bite marks—massive, with a jaw structure unlike anything in our databases.

“Dental impressions suggest a canine-type predator,” Dr. Cartwright said, voice clinical but strained. “But the size is all wrong. The jaw would have to be massive, at least twice the size of the largest wolf. The bite force calculation suggests something in the range of a large crocodile, but the tooth pattern is definitely mammalian. Canine, specifically.”

I knelt beside one of the bodies, studying the wounds. The victim’s face was frozen in terror, eyes wide, mouth open in a final scream.

“Time of death?”

“Between seventy-two and seventy-six hours ago. Early morning, probably between four and six a.m. They were attacked while sleeping. Two tried to run—didn’t get far.”

Sarah approached with her tablet, showing me a 3D reconstruction. “Look at the attack pattern. This wasn’t random predation. This was methodical. The creature approached from the northwest. Took out the victims in the tents first, then pursued the runners. The tracking pattern suggests the attacker was bipedal.”

“Bipedal?” I looked at her sharply. “You’re certain?”

She showed me images. “Seventeen clear impressions in the soft ground. Canine features, but arranged for upright locomotion—heel-to-toe gait pattern. Whatever made these tracks walks on two legs like a human, but with a foot structure that’s clearly not human.”

I felt the familiar cold sensation in my gut. The moment when you move from investigating an unknown animal attack to confronting something that defies everything you thought you understood about biology.

“Size estimate?”

“Seven and a half to eight feet tall when upright. Weight between four hundred and five hundred pounds. Massively strong.”

Dr. Cartwright showed me close-ups of the bite marks. “Look at this. The tooth pattern shows both crushing molars and tearing incisors. Typical of carnivores. But the arrangement—the canine teeth, these four here—are massive, over three inches long. And look at how they’re positioned. This isn’t a wolf’s jaw. The structure suggests something adapted for both tearing meat and maintaining a powerful bite grip. Something that hunts intelligently.”

“Intelligently?” I asked.

“The victims were armed. All four had high-powered hunting rifles. Three weapons were found at the scene. One had been fired twice. The other two showed signs of being grabbed and thrown hard enough to bend the barrels. Whatever attacked, these men understood what guns were and neutralized them before they could defend themselves.”

I studied the perimeter. Blood spatter, equipment, directional analysis. Sarah and Dr. Cartwright were right. This was an ambush by something that understood how to hunt humans.

“What does local law enforcement know?” I asked.

“We fed them the bear attack story,” Sarah said. “Aggressive male black bear, unusual for the season, but not unprecedented. The sheriff bought it. What else was he going to believe? The bodies were released to the families with instructions the caskets remain closed.”

“But we know better,” I said.

“We know it’s one of them,” Dr. Cartwright confirmed. “We’ve had reports from this region since the 1950s. Native American folklore talks about beastmen, walking wolves. Sightings reported by credible witnesses—hunters, rangers, law enforcement. The Program has been monitoring this area for decades, but this is the first time we’ve had a confirmed kill event with physical evidence.”

A dogman. That’s our classification. Not werewolf—Hollywood fiction. Not supernatural. A biological creature, flesh and blood, combining characteristics of canines and primates in a way that defied evolutionary biology.

We deployed trail cameras and thermal imaging drones across ten square miles. On the fourth night, we got our first visual confirmation. The trail camera triggered at 2:47 a.m. The image made everyone in the room go silent.

It was massive, easily eight feet tall, standing fully upright on two legs. The body was covered in dark fur, the build powerfully muscled, arms too long for the torso. The head was distinctly canine, wolflike but larger, heavier in the jaw. The eyes reflected green in the flash—intelligent, aware.

“Jesus Christ,” someone breathed. “It’s real.”

I was already suiting up. “Get me a location lock. I want a team in fifteen minutes.”

“Marcus, wait,” Sarah grabbed my arm. “Going in with a tactical team at night could trigger another attack.”

“That’s why I’m going alone. One person, no aggressive posture, no threat display. I need to observe it in its natural behavior before we make any containment decisions.”

Control authorized a solo observation mission with aerial support on standby.

I was dropped by helicopter three miles from the camera location. I moved through the dark forest alone, guided by GPS and thermal imaging, toward something that had killed four armed men without hesitation.

The forest at night in northern Wisconsin in March is a special kind of darkness. Every sound is amplified, every shadow a potential threat. I’d operated in combat zones, but this felt different. Primal.

I reached the clearing at 4:15 a.m. The location was empty, but the evidence was clear: massive footprints in the soft ground, claw marks on trees, and that musky, wild scent—stronger here, fresher.

I was studying the footprints by red-filtered flashlight when I heard it—a low growl, deep and resonant, from the treeline fifty yards to my left. It rose in pitch, becoming something between a howl and a roar. The sound carried through the forest, echoing off the trees. It wasn’t just loud. It was purposeful—a challenge, a warning.

I turned slowly, keeping my rifle lowered. My heart hammered, adrenaline flooding my system, but my training held. I couldn’t run. I couldn’t shoot unless attacked. Orders: observe, document, assess.

Then I saw it.

It emerged from the darkness between the trees. Even though I’d seen the photos, nothing prepared me for the reality. It was massive—eight and a half feet tall, powerfully built, covered in thick, dark fur. The arms were long, ending in hands with both humanlike dexterity and animal claws. The legs were digitigrade, walking on its toes like a canine, but the posture was fully upright. The head was distinctly wolflike, with an elongated muzzle full of teeth. Pointed ears swiveled to track sounds. But the eyes—God, the eyes—were intelligent, aware.

It was looking at me, not like prey, but like another thinking being, evaluating, deciding.

We stared at each other for what felt like an eternity, but was probably only thirty seconds. I kept my breathing steady, my posture neutral, my weapon down. The creature tilted its head, a disturbingly doglike gesture, studying me with those intelligent eyes.

Then it did something that changed everything.

It spoke—not in English, not in any human language, but it vocalized in a way that was clearly deliberate communication. A series of sounds with structure, pattern, intentionality. Not just growling or howling. It was trying to communicate.

I stood frozen, mind racing. If this creature had language, even a primitive one, it suggested cognitive capabilities far beyond anything we’d theorized. This wasn’t just an unknown animal. This was potentially an unknown intelligent species.

The creature watched me for another moment, then made a decision. It dropped to all fours and bounded away into the darkness—not running in fear, but moving with purpose, like it had assessed the situation and decided there was no threat or opportunity.

The next six weeks were a blur. Control approved a massive expansion of our operation. We brought in linguists, behavioral psychologists, evolutionary biologists. The Program established a permanent monitoring station disguised as a forestry research facility. We documented seventeen more sightings. Trail cameras captured images, thermal imaging tracked movement, we recovered physical evidence. DNA analysis confirmed samples were unlike anything in existing databases—showing characteristics of both canids and something else.

But the most significant breakthrough came from Dr. Ellen Mortonson, a linguist. “Marcus, you need to hear this,” she said, playing a recording from one of our monitoring stations. “Listen to the pattern. These aren’t random sounds. There’s structure here. Repetition, specific phonetic elements in consistent patterns. This is proto-language at minimum, possibly even true language. They’re communicating with each other.”

“How is that possible?” I asked.

She showed me anatomical models. “The throat structure isn’t exactly canine. It’s hybrid. Elements of canine anatomy, but with modifications for more complex vocalization. The larynx is lower, more like primates. The tongue shows increased flexibility. These creatures have evolved biological structures specifically adapted for communication beyond animal calls.”

If the dogmen possessed true language, it meant they had culture, social structure, possibly even history passed down through generations. This wasn’t just an unknown predator species. This was potentially an unknown intelligent species that had been living alongside humans, undetected by mainstream science for who knows how long.

We needed to attempt contact. Dr. Mortonson argued for it. I argued against it. “They killed four people brutally,” I said. “Whatever intelligence they have, they’ve demonstrated they see humans as prey or threats.”

“Or,” she countered, “those hunters stumbled into their territory, possibly threatened their young, and they responded the way any intelligent territorial species would: with defensive aggression. If we approach this right, we might be able to establish that we’re not a threat.”

The debate raged for weeks. Finally, in June 1987, authorization came for the contact protocol. A small team, myself included, would attempt controlled, non-threatening contact with one of the dogmen.

On June 23rd, 1987, I walked into a clearing alone, unarmed except for a tranquilizer pistol I prayed I wouldn’t have to use, and waited. The sun was setting, casting long shadows. I sat on a fallen log, making myself as non-threatening as possible. Food offerings were arranged nearby. Audio and video equipment was hidden in the trees. A tactical team was positioned a half mile away.

I waited forty-seven minutes. Then I felt it before I saw it—that sensation of being watched by something powerful. The temperature seemed to drop. The normal sounds of the forest went silent.

It emerged from the treeline to my right, moving with fluid grace. Massive, imposing, covered in thick, dark fur. But this time, it didn’t display aggression. It stood at the edge of the clearing, watching me with those intelligent eyes, assessing.

I stayed motionless, controlling my breathing. After a long moment, the creature took a step forward, then another. When it was about twenty feet away, it stopped and made a vocalization—a complex series of sounds that Dr. Mortonson had identified as a non-aggressive query, essentially asking, “Who are you?” or “What do you want?”

I had practiced this moment dozens of times, using the phonetic approximations Dr. Mortonson had developed. I attempted to respond in their language. The sounds were difficult, but I managed a rough approximation of the peaceful greeting pattern.

The creature’s reaction was immediate. Its ears perked forward, its posture shifted from cautious to interested. It tilted its head, made another vocalization—surprised, maybe curious.

We spent the next hour in what can only be described as conversation. Primitive, limited by my poor grasp of their language and the vast differences in our cognitive frameworks, but genuine communication nonetheless. Through vocalizations and gestures, I attempted to convey that I wasn’t a threat, that I wanted to understand, that we could coexist peacefully.

The creature—Alpha, I called him—demonstrated intelligence that exceeded anything we’d theorized. He understood pointing, followed complex gestures, showed clear problem-solving behavior. When I drew simple symbols in the dirt—representations of humans and dogmen living separately—he studied them, then modified the drawing with his own claw, adding details that suggested he understood.

As darkness fell, Alpha made a final vocalization, something that sounded almost like farewell, and retreated into the forest.

Over the following months, we had four more controlled encounters with Alpha and two with other individuals, including one that appeared to be female. Each encounter gave us more data. We learned they lived in small family groups, were primarily nocturnal, omnivorous but preferred meat, and avoided human contact deliberately, having learned over generations that humans were dangerous.

But we also learned darker things. The attack that had killed the four hunters wasn’t random. Through our communications with Alpha, we understood that those hunters had discovered a denning site where a female was raising two cubs. They’d approached too close, possibly threatened the young, and she’d responded with lethal force. From the dogman’s perspective, it was justified defense of family. From ours, it was four dead humans.

The ethical implications paralyzed the Program for months. What were our obligations? Did they deserve legal protection? Did they have rights? What happened if the public found out?

I wrote a 247-page report arguing for non-interference: designate large wilderness areas as protected territories for the dogmen, monitor to ensure no human casualties, but otherwise leave them alone. Let them live their lives in the forests they’d inhabited for thousands of years.

Others saw it differently. They argued that any species capable of killing humans so effectively was an unacceptable threat. The debates were fierce. In August 1988, the decision came down from somewhere far above my clearance: the dogmen would be classified as a cryptid species, protected status with active monitoring, and their existence kept absolutely secret. Any individuals that demonstrated aggression toward humans would be “contained”—a polite term for killed—but the species as a whole would be allowed to survive as long as they remained hidden.

I stayed with the Program for another twelve years, eventually becoming a senior field coordinator. I oversaw operations not just on the dogmen in Wisconsin, but on similar entities elsewhere. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, remote areas of Minnesota, possibly Idaho and Montana. We documented, monitored, and occasionally intervened when they came too close to humans.

The hardest part wasn’t the danger. It was the secrecy. I couldn’t tell my family what I really did. I couldn’t share the most extraordinary discovery of my life with anyone outside a small circle of cleared personnel. I watched as mainstream science remained ignorant of an intelligent species living right under their noses. I saw cryptozoologists ridiculed for believing in something I knew was absolutely real.

Over the years, I had dozens more encounters with dogmen. I learned more of their language, observed their social structures, their hunting strategies, their care for their young. I watched as human expansion pushed them into smaller and smaller areas. I documented their population decline—from 300–400 in the 1980s to perhaps 200–250 by the time I retired in 2000.

I left the Program at age forty-five. The psychological toll, the secrecy, the moral ambiguity ground people down. I was offered a desk job in Washington. I declined. I’d spent enough of my life keeping secrets.

But leaving the Program didn’t mean leaving the truth behind. I stayed in northern Wisconsin, bought property near the Chequamegon, and continued my own private monitoring—not for any agency, but for myself, for them. I felt an obligation to the species I’d spent so many years studying, to ensure their survival, even if the world never knew.

Now I’m seventy. The official secrets I carried are still classified, will probably remain so long after I’m dead. But I’ve watched as climate change and human expansion continue to squeeze the dogmen’s habitat. Their numbers decline further. And I’ve come to believe their best chance for survival might paradoxically lie in people knowing the truth—not the sensationalized versions, not the monster stories, but the truth: that there is an intelligent, nonhuman species, deserving of respect and protection, living in the wild places of North America.

They’ve been here far longer than we have. They’ve survived by remaining hidden, by being smarter and more careful than we ever gave them credit for.

I’m breaking my silence not to expose them to exploitation or harm, but because I believe public knowledge, properly managed, could lead to the habitat protection they desperately need. If people understood what’s really at stake, perhaps we could ensure their survival.

The government will deny everything I’ve said. The Program’s files are buried under classification levels that ensure they’ll never see daylight. Anyone I name is protected by operational security. I have no physical evidence I can share without violating federal law. This is simply my testimony—the account of a man who spent decades studying something extraordinary.

But I’ll tell you this: they’re real. The dogmen are absolutely real. They’re intelligent. They’re remarkable. And they’re disappearing.

Whether anyone believes me or not, I’ve told the truth. After forty years of silence, that’s all I can do.

And sometimes, late at night, when I’m out in the forest near my property, I still hear them. Those distinctive vocalizations carrying through the darkness. Alpha is long gone now, but his descendants are still out there, still surviving, still maintaining their ancient patterns of life in the few wild places we’ve left them.

I just hope it’s enough.