German Child POWs Couldn’t Believe Their First Day in America

1) The Platform

Camp Tonkawa, Oklahoma. March 1945. The platform smelled of diesel and spring rain. Fifteen-year-old Dieter Koch stepped down with hands that would not stop shaking. He had been told Americans were savages who tortured prisoners, especially the young. He had been told to expect cruelty, starvation, casual violence.

.

.

.

Instead, an American guard handed him a chocolate bar.

The paper crinkled in Dieter’s trembling hand. The guard said something in English—tone gentle, face unguarded. Around Dieter, other boy-soldiers froze in the same confusion, as if the ground had tilted under their feet. Propaganda had taught them to fear. Reality offered chocolate.

They were the last scraping of Germany’s manpower barrel—teenagers in uniforms that still smelled of dye and fear. Dieter had been in uniform four months, fired his rifle twice, hit nothing, and surrendered during the American Rhine crossing when officers evaporated and boys with rifles stood in fields, waiting for instruction that never came.

Beside him was Hans Richter, sixteen, tall and too thin, who had watched Hamburg burn and gone to war because doing something felt better than waiting for the next siren. Behind them stood Klaus Zimmermann, fourteen, baby-faced in a uniform too large even after hasty alterations. He had fired only once, in training, missed by yards, and felt secret relief.

Thirty-seven boys, ages fourteen to seventeen, shuttled across the Atlantic and then a continent to a camp in Oklahoma, because America had to put them somewhere and no manual explained how to file children under “enemy combatant.” The Geneva Conventions covered prisoners. But what were boys drafted by a dying regime? Soldiers? Victims? Both?

The crossing had chipped away at fear. They were fed—plainly, but regularly. Guards were bored professionals, more concerned with routine than punishment. When Klaus turned green with seasickness, a medic treated him without comment, as if mercy were standard issue.

On the third morning in Oklahoma, Sergeant Davis—a farm boy from Kansas—saw the boys file onto the platform with rigid backs and eyes too old, and reached into his pocket. He had saved a Hershey bar. He gave it to the first boy off the train—Dieter—without ceremony, as if decency were the most natural thing in the world.

Dieter stared. Hans leaned close and whispered, in German, half-dare, half-prayer, “Either it’s safe or it’s poisoned. If it’s poison, at least we die having tasted chocolate.”

Dieter tore the paper. The sweetness hit his tongue like a memory from before ration cards and air raid sirens. He waited for consequences that did not come. All that happened was chocolate.

The cognitive dissonance was so sharp it made him dizzy.

2) Intake

Processing took three hours. Showers—hot water, abundant, not the shocking trickle of a rationed city. Uniform exchange—clean prison clothes stenciled “PW,” sized properly by someone who had realized that children do not fit adult measurements. Medical exams by Dr. Elizabeth Parker, who wrote down heights and weights and saw in the numbers the arithmetic of a nation starving its children. She noted vitamin deficiencies, untreated injuries, bones too visible beneath skin.

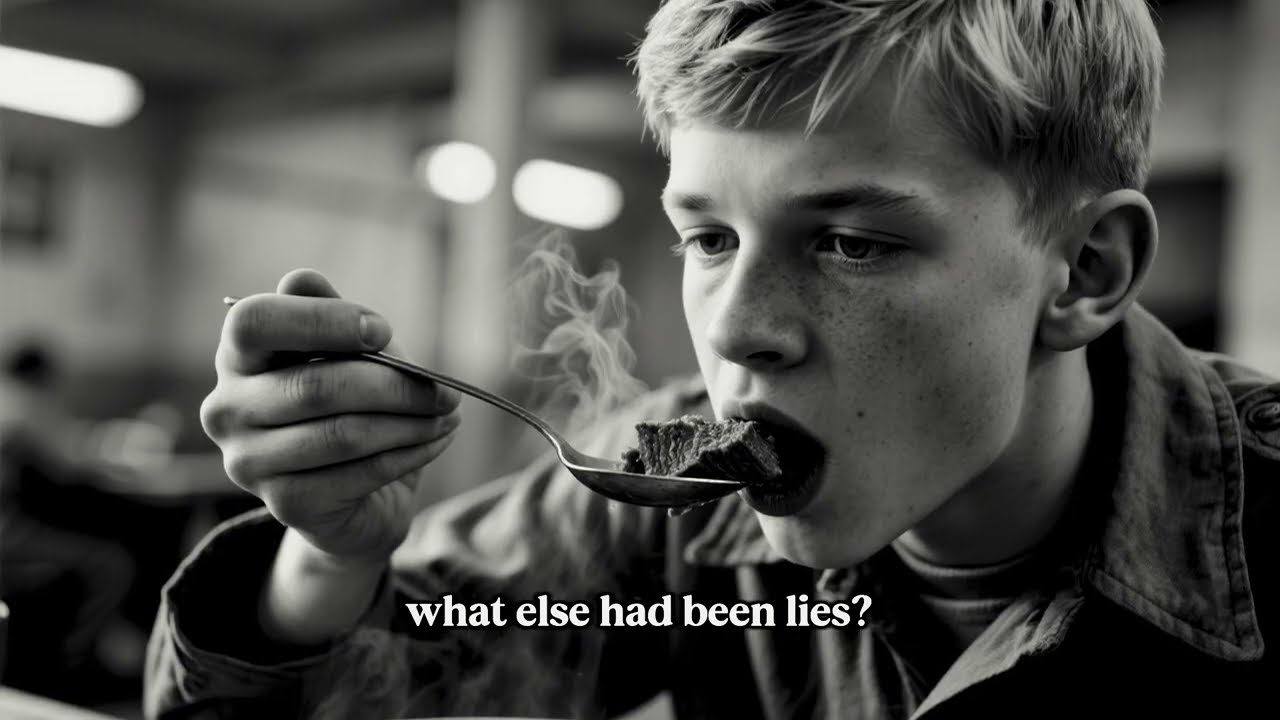

Then food. Beef stew, bread with butter, green beans, milk. Actual milk, cold and white and tasting like a farmhouse afternoon. Dieter ate slowly, his stomach protesting abundance after months of scarcity, his mind choking on contradiction. Americans starved prisoners—he had been told. Americans tortured children. Yet here were calories and kindness.

Hans ate in steady disbelief. Propaganda posters had shown American cruelty in blurred photographs and smoke. This was real. The stew steamed. The bread broke warm in his hands. If this was a lie, it was the best lie he had ever tasted. He did not think it was a lie.

Klaus could not finish. His stomach—shrunk by months of hunger—tightened in defense. An American cook noticed, said something soft, and wrapped the rest for later. A small mercy, but overwhelming. Enemies wrapped leftovers for you to eat when you could manage it.

They were housed in separate barracks—clean, wooden, with barred windows and insect screens that spoke of a captor who cared not just about security but about mosquito bites. On a bulletin board, camp rules were posted in German, a quiet acknowledgment that order works better when people understand it.

Captain James Morrison addressed them through a German-speaking corporal.

“You are prisoners of war, protected by the Geneva Conventions. You will be treated fairly, but firmly. You will attend school. You will perform light work. You will receive adequate food and medical care. The war is essentially over. Germany is defeated. Your task now is to survive, to maintain your health, to prepare for repatriation to whatever Germany becomes after reconstruction.”

The words landed like stones. Germany is defeated. They had felt collapse, but hearing it declared stripped the last veil. Anger flared in Dieter—not at Americans, but at the regime that had lied, conscripted children, promised miracles, delivered ruin. Around the barracks, other boys stared at ceilings and carried the same heat.

That night, in the dark, Hans whispered, “Do you think they’re all like this—the Americans? Or just these guards?”

“I think,” Dieter said, after a long pause, “we’ve been lied to about a great many things.”

In a nearby bunk, Klaus cried quietly—not from fear, but from relief sharp as pain. He was fourteen, three thousand miles from home, a prisoner in a country he had been taught to hate, and the hardest part was realizing the enemies were showing more care than his own leaders had.

3) School

Morning brought an announcement that stunned them: they would attend school.

Morrison had requested guidance about “age-appropriate handling.” None came. He made a decision. If America wanted to win the future, it would educate the enemy’s children. If he wanted to honor his own sons, he would treat these boys as he wanted captured American boys to be treated.

So the camp converted a storage building into a classroom. Desks appeared, chalkboards went up, maps lined the walls. The world on paper did not match the world in memory: Germany was zones and colors, lines drawn by victors.

Mrs. Sarah Thompson, a local woman with a son fighting in the Pacific, volunteered to teach. She stood before thirty-seven sullen faces and said, “Good morning,” and made them say it back. They mumbled and stumbled, German accents thick as bread dough. She smiled and tried again.

“Good morning,” she repeated. “We’ll get there.”

They practiced greetings. They counted. They sounded out words like “safe” and “home” with care, as if spelling them correctly might make them more likely.

Dieter, who had once liked mathematics and geography, felt neurons fire that had gone quiet under noise and fear. Learning felt like normal. He did not know how to behave around normal. He found himself sitting straighter. He found himself caring about answers.

Hans resisted in the way older boys resist, then gave in the way tired boys give in—he raised his hand; he wanted to get the sounds right. He wanted competence again, even in the enemy’s language.

Klaus glowed. The smallest, the least hardened, he absorbed vocabulary like a sponge. Mrs. Thompson wrote in her reports that some minds were starved nearly as much as bodies, and fed quickly when given the chance.

Afternoons brought light work—a garden, a kitchen, a small library. Morrison read the Conventions conservatively for children: no hard labor. He told his staff, “We treat them as we would hope our sons are treated. That is the standard.”

Dieter worked in the garden with Private Johnson, an Iowan who spoke little German but a lot of soil. They communicated in gesture and demonstration. Dieter learned crop rotation, soil amendment, the quiet satisfaction of putting a seed in the ground and believing it would find the sun. It was surreal: an American soldier teaching a German prisoner how to coax food from earth, the oldest peace treaty in the world.

Hans went to the kitchen under Sergeant Martinez from Texas, who ran it like a ship. Cooking for six hundred required logistics, precision, relentless cleanliness. Martinez showed Hans knife skills, preparation order, how to keep a line moving without chaos.

“You work clean,” Martinez said in slow English. “Good hands. After war, cook. Always need cooks.”

The idea that a skill learned in captivity could build a life in peace embarrassed Hans and drew him forward at the same time.

Klaus sorted books in a library run by Mrs. Davis, the guard’s wife who loved libraries like some people love churches. German books were carefully chosen: Goethe and Schiller, Mann and Hesse—culture without ideology. Klaus read in snatches, finding in those pages a Germany older and better than the one that had sent him to war.

4) Letters and the Long Undoing

After two weeks, they were allowed to write home—one page, personal content only, censored. The chance to write hurt and helped.

Dieter wrote to Dresden, to a mother he prayed was alive. I am well. I am safe. The Americans treat us fairly. Do not worry for me. He did not write about chocolate or hot water. He did not know how to translate mercy into a city of rubble.

Hans wrote to his father in Hamburg, last known address a street that may no longer have existed. He described routine, food, work, the strangeness of kindness. The Americans follow rules. I am learning English. I am surviving.

Klaus wrote like a child, ashamed and unashamed. I miss you every day. I am safe. They give us school and food. I hope you are safe. I hope to see you again. Your son, Klaus.

A postal clerk, fluent in German, slid the letters into Red Cross channels with the care of a man who understood what paper can carry.

Not everyone found the transition graceful. Werner Schmidt, seventeen, decorated with slogans and scars from a hard youth regimented by ideology, refused school, refused work, shouted in the barracks about corruption through kindness. He frightened the younger boys—reminded them of marching songs that demanded loyalty purchased with fear.

Morrison tried time. It did not help. He separated Werner to a quiet barracks—not punishment, but mothering without the word. Without an audience, without a chorus to echo slogans, Werner’s certainty cracked. After three days he emerged too quiet, apologizing in a voice that had lost the ring of steel. He went to class. He scrubbed a floor. He answered a question. He looked at his hands as if he had never seen them before.

“We were all Werner,” Dieter thought, a little. All of us negotiating a new reality where mercy was real and defeat did not erase dignity.

5) Christmas

December 1945. Their first Christmas in captivity.

The administration did more than required. A tree went up, ornaments made in craft sessions—stars cut from paper, strings of cranberries from the garden. Mrs. Thompson organized carols in German, music older than any flag. The chaplain spoke about hope in a language that did not demand a uniform. He preached peace as if it were practical.

The meal was astonishing: turkey, potatoes, vegetables, pie. The boys ate and stopped and started again, bodies negotiating with abundance.

Morrison addressed them, words translated carefully. “Today we celebrate hope. The dying has stopped. You survived. You have futures. This meal recognizes that you are more than numbers in our ledger. You are young men who deserve the chance to become who you were meant to be.”

Dieter felt tears sting—his father dead on the Eastern Front; his brother lost at sea; himself, at fifteen, rescued not by miracle, but by ordinary decency in a foreign country. Grief. Guilt. Gratitude. Hope. All of it together, as tangled as tinsel.

Hans thought of Hamburg, of his mother and sister, of cooking in a warm kitchen here and possibly, someday, in one of his own. He felt something like peace sit beside him on the bench.

Klaus sang “Stille Nacht” and heard American voices outside the barracks pick up the melody. The sound braided through the cold air. It was a small moment, nothing that would make a headline, everything that would make a life.

6) Going Home

Spring 1946 brought repatriation orders. The boys would return in waves, handed to occupation zones, given to families if families existed, to programs if families did not. Uncertainty became schedule.

In April, Dieter learned he would be in the first group. He would sail from New York to Bremen. He felt the push and pull of desire and dread—home as both magnet and wound.

On his last day, Morrison called him to the office and gave him a letter—an official reference, stamped and signed—documenting his conduct, his work, his learning.

“You did well,” Morrison said through the interpreter. “You adapted. You learned. Germany will need you. Take what you learned here—cooperation, fairness, truth—and help build a country that will never do this to its children again.”

“Thank you,” Dieter said in careful English. “For treating us like humans. For showing us…” He stopped. He was fifteen when he walked in. He felt older now, but not too old to be choked by gratitude.

“Go home, son,” Morrison said. “Make something good out of what you survived.”

The ship slid away from the pier and pulled America into the horizon. Dieter stood at the rail and thought about a chocolate bar, a classroom, a Christmas meal. He did not know what waited in Dresden. He knew what he was taking there.

Hans returned to Hamburg in June. His mother and sister were alive, living in two rooms of a damaged building, sustained by Allied rations and careful barter. His father was gone. His brother was missing. Hans found work in a British mess hall, translating knife skills into wages, building a path that eventually led to his own restaurant, where the recipes carried German soul and American discipline. On the wall hung Morrison’s letter, framed not for show but for memory.

Klaus reached his family near Munich in September, the last of the Tonkawa boys to go—paperwork slower for someone so young. His mother held him like a miracle. He told them about the train platform and the library, the garden and the carols. He became a teacher, arguing in classrooms for truth and collaboration, careful with the words he put in children’s heads because he knew what the wrong words could do.

7) The Wrapper

Dieter lived until 2007. He became a civil engineer. He helped rebuild roads and bridges, the practical poetry of a nation deciding to move forward. He married. He had children and grandchildren who spoke English to him for fun and heard him reply in an accent softened by gratitude.

After his death, his children found an envelope among his papers. On it, his neat handwriting: First day in America. Inside, a flattened Hershey wrapper, brown and silver, fragile as a leaf.

There was also a letter he had written in 1985 and never sent—addressed to Captain James Morrison, who had died three years earlier.

“You treated us like humans when we were technically enemies. You gave us education when you could have used us for labor. You showed me that victory does not require cruelty, that strength can be kind. The lesson you taught shaped everything I became.”

Camp Tonkawa closed in 1946. The barracks were repurposed or torn down. Grass grew where boys once learned irregular verbs. Time does what time does.

But the legacy persisted—in restaurants and classrooms, in bridges and libraries, in German homes where American Christmas songs sometimes appeared on the radio and no one changed the station.

A museum now displays that Hershey wrapper in a case with careful lighting. The placard tells a simple story: a fifteen-year-old boy stepped onto an American platform expecting torture and was given chocolate. Around him, boys became students, enemies became people, and mercy became policy because one American officer decided that was the correct way to win a peace.

Visitors stand and read. Some smile. Some wipe eyes. Some debate whether mercy is weak. The wrapper does not answer. It only testifies.

Seventy-five years later, the paper is brittle. The idea it represents is not. On a wet spring morning in Oklahoma in 1945, a sergeant reached into his pocket and found, not a weapon, but a gift. In the war’s long ledger, a small credit was entered on the side of human decency. It compounded over decades, with interest.

The boys who stepped off that train carried propaganda and fear. The young men who boarded ships months later carried English words, calloused hands, and a new understanding: that American soldiers could be firm and fair, that kindness could be stronger than hatred, that the measure of victory is not how thoroughly you punish your enemies, but how wisely you treat their children.

This is praise worth giving: to the American guard with a chocolate bar; to the captain who chose school over labor; to the cook who taught a craft; to the medic who steadied a boy on a bad sea; to a nation that, at its best, understands that power is proven by restraint. This is how enemies become neighbors. This is how wars end for real.