German POW Grandmothers Were Left to Die — U.S. Soldiers Carried Them 12 Miles to Medical Care

Twelve Miles of Mercy (Bavaria — April 1945)

Chapter 1 — The Clearing in the Pines

The road through the Bavarian forest was barely a road at all—mud, broken stone, and ruts cut by desperate traffic. Morning mist hung low between pine trunks, softening the edges of a landscape that had been bruised by war.

.

.

.

Corporal James Sullivan, medic with a U.S. Army medical detachment attached to the 45th Infantry Division, had learned not to expect surprises. For two years he had patched men together in France, Belgium, and Germany. He had learned how fast a body could empty itself of blood, how quiet a dying man could become, how a scream could turn to a whisper. He thought he knew what shock felt like.

Then the detachment found the clearing.

It wasn’t an official camp, just an improvised holding place—branches bent into crude shelters, cold fire pits, scattered belongings. Whoever had been here had left in a hurry. Retreating forces had moved the able-bodied onward and abandoned what slowed them down.

Three elderly German women lay on rough stretchers made from blankets and broken branches, their breathing shallow, their bodies sagging under pneumonia, exhaustion, and the long starvation of a collapsing country.

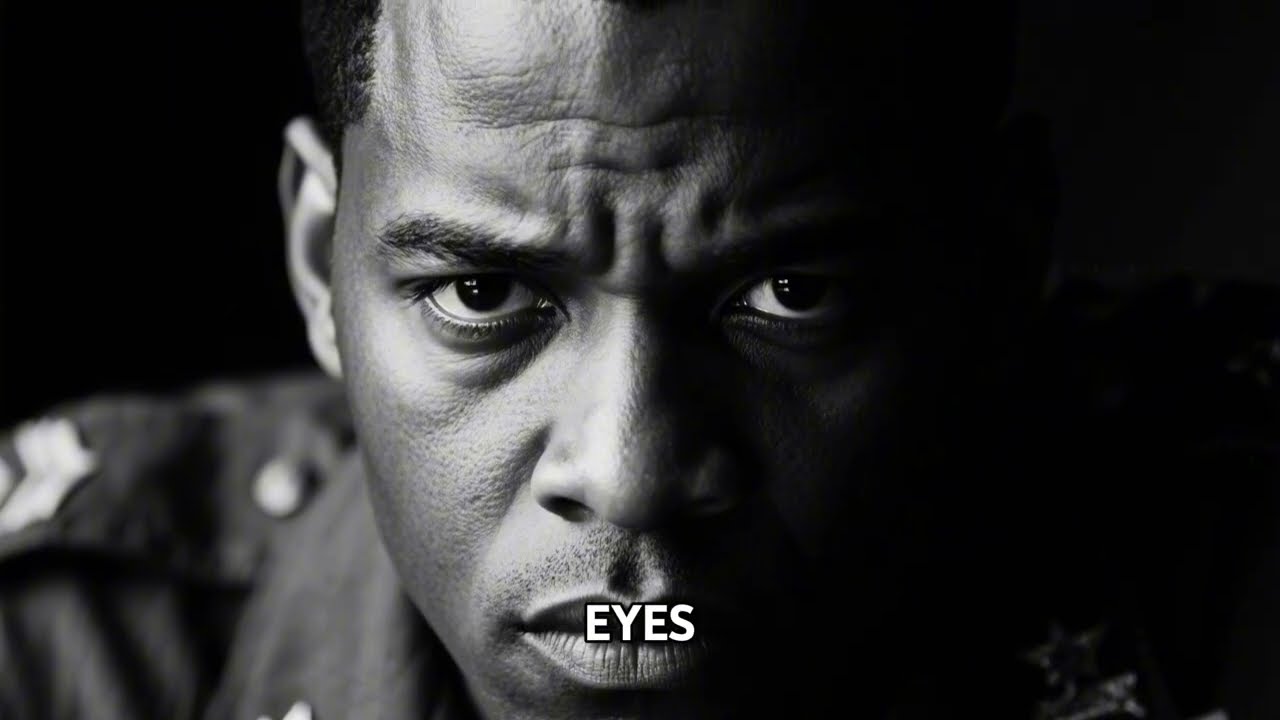

Sergeant Marcus Washington, the senior NCO, knelt beside the nearest woman and listened to her lungs. The sound was wet and heavy, like a river trying to push through mud.

“Pneumonia,” he said, quick and certain. “Advanced.”

Sullivan stared at the women’s faces and felt his training pause, just briefly, under the weight of what he was seeing. These were not soldiers. Not the men they had fought. Not even prisoners of war in the usual sense.

They were grandmothers.

Private Danny Chun, the unit’s translator—an American born to Chinese immigrant parents, educated, careful—spoke in German to the woman whose eyes still tracked movement. She was Fra Bergmann. The others were Fra Keller and Fra Schmidt. All from a village about thirty kilometers away.

German forces retreating ahead of the American advance had taken civilians with them—young, healthy, useful. The old and sick had been left behind because they consumed time and food and slowed down men with weapons.

They had been here three days, maybe four. Fra Bergmann had managed to bring water from a stream. There was no food. No medicine. Only thin shelters against April cold.

Fra Bergmann whispered something in German, and Chun translated quietly.

“We were told the Americans would come,” she said. “We were told you might help… or you might not.”

The sentence ended in the air like a prayer that had run out of breath.

Sullivan looked at Washington. The sergeant’s face was steady, but the calculation was obvious. Their orders were to support forward movement, not to become caretakers for enemy civilians. Civilian complications were supposed to be handled later, by other units, by displaced-persons camps, by paperwork.

Paperwork did not stop pneumonia.

The nearest field hospital with adequate supplies was twelve miles away.

Twelve miles might as well have been another world.

Chapter 2 — Lieutenant Morrison’s Choice

A half mile back on the passable section of road, Lieutenant Thomas Morrison waited with the jeep. He was twenty-four, promoted after his predecessor died in Belgium. He carried the heavy, quiet burden of command: decisions made in minutes that echoed for years.

Sullivan jogged back to him through damp pine air that still smelled faintly of cordite.

“Sir,” Sullivan said, “we’ve got a situation.”

He explained what they had found: three elderly German women, dying, left behind, the road ahead blocked by craters and fallen trees. Vehicle transport was impossible. Carrying them would take most of a day and pull the detachment off its assigned route.

Morrison listened without interrupting, eyes fixed on a map as if maps could offer moral answers.

“Their civilians?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” Sullivan said. “They’ll die without treatment.”

Morrison was silent for a long moment. Then he folded the map and stood.

“Show me.”

At the clearing, the lieutenant examined the women with the brisk detachment of someone trained to assess bodies under pressure. His eyes moved from Fra Keller’s gray face to Fra Schmidt’s shallow breaths and then to Fra Bergmann’s frightened gaze.

“This will take us off route,” Morrison said to Washington. It was not a complaint; it was a fact.

“Yes, sir,” Washington replied. “Command won’t like it.”

Morrison looked at the three women again, then at his medics—young men from Iowa and Tennessee and elsewhere, tired, muddy, already carrying too many images inside them.

“But we can’t leave them,” Morrison said.

It wasn’t phrased as a question. It was a statement of who they were trying to remain.

Washington nodded once. “No, sir.”

“All right,” Morrison said. “Improvise stretchers. Stabilize them as best you can. We move out in an hour.”

Then he keyed the radio and reported a civilian medical emergency, requesting approval to deviate for evacuation.

The reply came sharp and immediate: negative. Their mission was forward support. Civilian casualties were secondary. Do not deviate.

Morrison stared at the handset as if it had offended him.

Then he radioed back, voice controlled.

“Respectfully, we cannot leave critical patients to die. We are proceeding with evacuation. Morrison out.”

He turned the radio off before argument could follow.

His men understood what that meant. Disobeying a direct order during operations was no small thing. It could cost a career. It could bring discipline. It could stain a record.

Morrison did it anyway.

He did it without drama, without announcing virtue. He simply decided that the United States Army would not become a second force that walked away from dying women in the woods.

“Let’s move,” he said. “We’re burning daylight.”

Chapter 3 — Stretchers from Branches, Medicine from Packs

Private Tommy Walsh, a carpenter before the war, used his folding saw and practiced hands to cut pine branches to length. He lashed frames with paracord and canvas salvaged from gear. The stretchers were crude but strong—two poles, cross-braced, canvas slung tight enough to distribute weight.

Chun helped, following instructions, learning improvised engineering that wasn’t in any training manual.

Sullivan focused on care.

Fra Keller was worst. Her fever was high, pulse racing and weak. Sullivan crushed sulfa tablets into water and coaxed what he could into her mouth. He wrapped blankets around her, careful to keep warmth without trapping too much heat.

Fra Schmidt could still swallow. She watched Sullivan’s hands with confusion, as if she expected them to change into fists.

Fra Bergmann was alert enough to talk. Chun sat beside her, speaking gently in German.

“We will carry you to a field hospital,” he explained. “They have antibiotics. Oxygen. Proper care.”

Fra Bergmann stared at him. “Why?” she asked. “We are Germans. You are Americans. Why would you help?”

Chun searched for words strong enough and simple enough.

“Because you are sick,” he said finally. “Because we can help. Because leaving you would be wrong.”

Fra Bergmann’s face crumpled. She began to cry—not from pain, but from the shock of mercy arriving where abandonment had been expected.

“My grandson,” she whispered, struggling to breathe through sobs. “He is a soldier somewhere in the east. We have no letters. He might be…”

Chun nodded. He did not force her to finish. “I hope he’s alive,” he said quietly. “And I hope if he needs help, someone shows him the mercy we’re showing you.”

The stretchers were finished by midday. Washington organized the carrying teams. They would rotate every hour to share the burden, take breaks, drink water, check pulses, and keep moving.

The plan was simple.

The work would not be.

Chapter 4 — The First Miles

The first hour punished them immediately.

Sullivan and Morrison carried Fra Keller. The poles dug into shoulders and the stretcher tugged with every uneven step. Mud tried to steal boots. Roots and rocks demanded constant attention. The forest was beautiful in a way that felt cruel—mist, pine scent, cool air—because beauty had no power to stop lungs from filling with fluid.

They walked in silence except for warnings: “Root,” “hole,” “log.”

After an hour, Morrison called a halt. They set the stretchers down gently and rotated. Sullivan moved to Fra Schmidt; Walsh took Fra Keller with Morrison stepping briefly into the unburdened rotation.

Chun checked Fra Keller. Her breathing had worsened. The gray tint deepened around her mouth.

“She’s failing,” Chun said.

Sullivan adjusted blankets and tried to keep his hands steady. “We keep moving,” he answered.

By the second hour, muscle fatigue set in. The weight of the stretchers did not decrease; it became more personal, more intimate, as shoulders bruised and skin began to tear beneath fabric. Sweat soaked uniforms despite the cold. Each breath began to feel like work.

Walsh, carrying Fra Bergmann with Washington, heard the woman whisper prayers in German. Later Chun translated: prayers for her grandson, prayers for the men carrying her, prayers for an end to the war before it consumed everyone.

At the two-hour mark they reached the jeep. The road beyond was passable, flatter. But the remaining distance still loomed.

Morrison tried the radio again. Command repeated the direct order to stop the evacuation and return to assigned route.

Morrison acknowledged the order. Then he spoke truth into the handset, knowing it would not be welcomed.

“These patients will die if abandoned,” he said. “I accept responsibility. We are continuing.”

Silence followed—either command gathering words, or deciding it was useless to argue with a lieutenant who had already chosen who he was going to be.

They continued.

Chapter 5 — When Fra Keller Stopped Breathing

By the fourth hour, their bodies were raw. Poles rubbed skin away. Hands cramped. Legs shook with fatigue. Yet the rhythm of movement became its own discipline—lift, step, breathe, adjust, step again.

Then Chun called sharply. “Stop.”

Fra Keller had stopped breathing.

Sullivan dropped his end of the stretcher and moved to the woman’s head. Airway clear. No breath.

Washington began compressions immediately, arms straight, jaw clenched.

Sullivan performed rescue breathing, forcing air into lungs that resisted. One breath, two, three—counting, keeping pace with compressions, refusing to give up simply because war had taught them that giving up was easier.

Minutes stretched.

Then, a gasp.

Weak, barely present—but real.

Fra Keller’s chest rose on its own. Her heart returned in an irregular rhythm, frightened and stubborn.

Sullivan administered morphine in a careful dose. It would blunt pain and stress, though it risked suppressing breathing. But pain itself was killing her too.

They lifted the stretchers again and moved faster, the urgency now sharp as a blade. Fra Keller could fail again at any moment. Time was running out. Mercy could still be too late if they didn’t finish the job.

The fifth hour was pure will. Pain passed into numbness, and numbness frightened them more than pain because it meant damage. Morrison’s shoulders bled beneath his jacket. Washington’s hands shook slightly when he wasn’t carrying. Rodriguez began humming under his breath to keep rhythm and keep panic out of his throat.

They did not stop.

Because stopping would make them the second group of soldiers to abandon these women.

And they would not wear that.

Chapter 6 — The Aid Station at Sunset

Near the end of the eighth hour, they saw it: tents clustered around a farmhouse, vehicles, smoke from incinerators, the organized chaos of a forward aid station.

Morrison radioed ahead. “Three critical civilian patients. Advanced pneumonia. Arrival fifteen minutes.”

A doctor’s voice responded. “We’re ready. Bring them straight in.”

The final mile felt longer than the first twelve. Sullivan’s vision narrowed to the pole on his shoulder and the mud underfoot. He kept walking because there was nothing else to do, because carrying was the only argument he had left against the cruelty of the world.

They reached the aid station as the sun slid toward the western ridge.

Doctors and nurses swarmed the stretchers—oxygen, fluids, antibiotics, rapid assessments. The women were moved into tents with clean sheets and equipment that looked like salvation.

Only then did the medics allow their bodies to fail.

Morrison leaned against a tent pole and slid down, shoulders seizing in cramps. Sullivan sat on the ground, shaking. Washington pulled off his jacket and found the skin beneath torn and bleeding where the poles had rubbed.

Major Hawkins, the gray-haired physician in charge, approached Morrison.

“Who authorized this evacuation?” he asked.

“I did,” Morrison replied. “Against orders.”

Hawkins studied him a moment. “You’ll face consequences,” he said. “But you did the right thing. They would have died.”

Morrison nodded. “Yes, sir.”

In the days that followed, the women survived. Penicillin and oxygen and steady care did what willpower could not. Fra Schmidt improved quickly. Fra Bergmann took longer to recover emotionally; she kept asking why Americans had helped when her own side had left her.

Chun answered patiently each time: “Because we could. Because it was wrong not to.”

Morrison was reprimanded for insubordination—officially noted, unofficially softened by a truth many commanders understood but could not say loudly: discipline matters, but decency matters too. In a war with plenty of necessary violence, small acts of mercy were not weakness. They were proof that the fight had meaning.

Two weeks later, before the women were transferred to a displaced-persons camp, Fra Keller asked to see the men who had carried them.

She thanked them in German, voice thin but steady. No translation was needed to understand her eyes.

“You carried us when your own people would not,” she said. “We will remember. We will tell the truth.”

Sullivan felt tears and did not hide them. Washington simply nodded. Morrison managed a few German words he had learned from Chun.

“We did what was right,” he said. “That’s all.”

Twelve miles through a Bavarian forest did not change the war’s outcome.

But it saved three lives, and it left behind a different kind of victory—quiet, stubborn, and enduring: the victory of men who chose humanity when the easiest thing would have been to walk away.