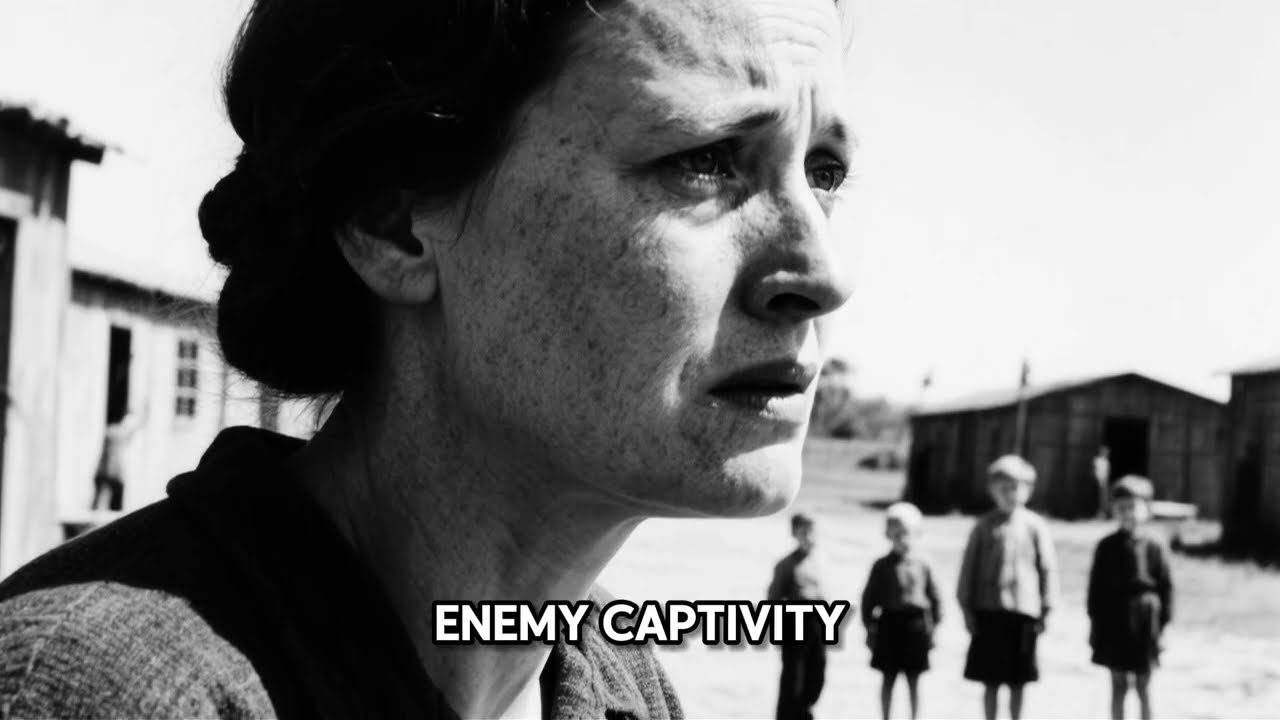

German POW Mother Watched American Soldiers Take Her 3 Children Away — What Happened 2 Days Later

1) The Dust and the Door

Arizona, August 1945. Dust hung in the air outside Camp Papago Park, turning the afternoon sun into a copper coin. In the women’s compound, where barracks stood in neat white rows against the brutal geometry of the Sonoran Desert, Katherina Weber held her breath as two American soldiers approached her children. Seven-year-old Hans; five-year-old Greta; three-year-old Emil. The soldiers used gentle tones she did not understand, hands open, gestures soft. The truck idled. Her children looked back at her with eyes full of questions she could not answer.

.

.

.

They climbed into the tailgate with the obedience of the frightened. The truck pulled away, carrying them into a storm of light and dust.

Two days later, what returned would rewrite everything she thought she knew about enemies.

Katherina’s story had begun six months earlier, in February 1945, when the ship carrying her from Europe docked in New York Harbor. She was thirty-two, widowed, a mother of three who had never known peace longer than a season. Her husband had fallen in North Africa in 1942. She had worked as a clerk in a depot near Munich while the ground gave way under an empire built on lies. Propaganda had trained her expectations: Americans were vengeful. Americans were cruel. Captivity would mean humiliation, hunger, punishment.

Instead, Ellis Island offered bureaucracy: forms in triplicate, medical examinations, clerks who looked tired rather than hateful. Efficiency, not vengeance.

Then the trains west: days and nights through a country that felt impossible in its intactness. Cities with skylines rather than scars. Fields unbroken by craters. Faces that stared through windows with something closer to curiosity than hatred. The children pressed their foreheads to the glass. Hans asked why all the buildings were standing. Katherina had no answer she could say aloud.

Camp Papago Park sprawled across seven hundred acres of desert north of Tempe—originally built for Italian POWs, expanded to hold Germans. By 1945 it held over three thousand men and, in a separate small compound, forty-seven German women and their children. The women’s section had been built with a kind of reluctant kindness: smaller barracks altered for families, a makeshift classroom where teenagers taught younger children letters and numbers, a kitchen where German recipes wrestled with American rations and won just often enough to be called dinner.

Katherina and her children were assigned to Barracks 7 with four other families, fifteen people in a space designed for eight. Privacy evaporated; personal space shrank to inches. But there were beds. There was food. There was safety from fire falling out of night skies.

Children adapt faster than grief allows. Hans found other boys and invented games in the yard, using rocks and sticks to draw a world not encircled by wire. Greta stood on a crate in the kitchen to reach the counter and learned to knead American bread—wrong taste, right nourishment. Emil chased lizards until lizards became a fact not worth chasing. Katherina watched their acceptance and felt relief and guilt in equal measure. Survival in enemy custody was still survival. But what did it mean?

In July, measles slipped into the compound like a thief. It started in Barracks 3 and spread the way contagion always does in close quarters. Hans first—fever like a furnace, rash painting his skin in a cruel red punctuation. Then Greta. Then Emil. The camp doctor, Captain Richardson, examined them, wrote notes, spoke English words that landed more as tone than meaning: monitor, fluids, watch for pneumonia, encephalitis. Katherina understood the essential: danger.

She slept in snatches, waking to spoon water into heat-mouthed children, laying cool cloths on foreheads that would not cool. The small infirmary strained—seventeen children sick, three critical, three exhausted medical staff doing everything possible, which was not the same as everything needed.

On August 3, Emil’s fever slammed to 105. His breath came with a wet rattle that made Katherina’s blood remember her brother’s funeral. She called for Richardson in a voice that broke itself.

He came. He looked. His face changed.

“This child needs hospitalization,” he said. “Real facilities.”

The words dissolved against Katherina’s limited English. She understood his urgency. That was enough. Richardson requested emergency authorization to transport three German children to Phoenix Memorial Hospital: Emil, and—because separation would be its own harm—Hans and Greta, too.

The request moved like lightning through the wire of command: camp commander, military government, civilian liaison. Geneva obligations weighed against public perception: German prisoners receiving civilian care when American boys were still dying in the Pacific? In six hours the answer came back: authorized. The children would go to Phoenix Memorial. They would receive care commensurate with medical need.

Katherina would not be going with them.

Regulations forbade it—security, liability, the impossibility of guarding a prisoner in a civilian hospital. The interpreter—one of the German women who spoke serviceable English—translated while Katherina’s world fell away. “No,” she said in German. “No. They are babies. They need their mother.”

“I’m sorry,” the doctor said, and meant it. Regulations were a wall made of paper and steel.

At 1400 hours on August 4, an ambulance idled at the compound gate. Two American corpsmen lifted Emil onto a stretcher, their hands careful, their voices gentled to soothe fear they could not erase. Hans and Greta climbed into the vehicle, faces hot with fever and dread. Through the back window, Hans pressed his palm against the glass, as if he could pass his hand through it into his mother’s. Greta’s sobs had gone silent, small body quaking without sound. Emil’s eyes searched for his mother and did not find her.

Katherina watched until dust erased the road. Then she went back into Barracks 7 and lay staring at three empty beds. The other women tried to comfort her with whispers and touches. Sympathy rose and fell in the room like breathing. It changed nothing.

2) The Ward

Phoenix Memorial Hospital sat clean and white on the city’s northern edge—built in better years, equipped beyond what field medicine could improvise. Staff had been notified. Discussions had been had. A few nurses objected, quietly: enemy nationals while American boys bled? Others said a child is a child. The administrator made a decision: admit. Treat per medical necessity. Guards posted. Keep the story simple and decent.

The children were placed in a private room—for practicality as much as privacy. Two military police took chairs outside the door. Inside, Mary O’Brien, fifty-three, veteran of twenty-seven years of nursing, walked in expecting three problems to be solved. She found three children calling for their mother in a language she did not speak.

Hans tried not to cry. At seven he had decided men do not, and he clung to the decision even as tears leaked from the corners of his eyes. Greta sobbed and clutched a cloth doll that was coming apart one stubborn stitch at a time. Emil lay limp and burning, breath shallow and noisy, body in small rebellion.

O’Brien felt something crack inside the armor experience builds. She moved to Emil first. Forehead: hot. Lungs: laboring. Skin: rash like a map of heat. “Let’s go,” she said to the nurse behind her. “Antibiotics. IV. Cool cloths. Oxygen. Keep talking to him, even if he can’t understand.”

The next forty-eight hours narrowed to tasks done right and done again. Emil’s fever broke on the second day, shamefaced and slow. He opened his eyes and saw in O’Brien not an enemy but a person, because that is what very small children see unless taught otherwise. Hans and Greta improved more quickly, fevers lowering, rashes fading to a dry geography. Their fear did not lower with their temperatures. Their language wrapped around worries and held tight: Mama? When? Why us?

On the evening of August 6, Mary O’Brien broke a rule she had learned to obey. She sat on the edge of Greta’s bed and sang. Not German—she had none. An old English lullaby her own mother had sung when the world was simpler: Hush, little baby. The melody was a hand over a frightened heart. Greta did not understand the words. She understood the intention. She fell asleep with the broken doll pressed to her chest.

In the morning, Hans stood straight as seven and said to O’Brien in careful English, “Thank you.” The words lodged inside her like a vow.

That night O’Brien went to the pediatrician’s office. Dr. Harold Chun, chart-weary and conscientious, looked up. “They’re improving,” he said. “The little one will be clear for discharge in three days. The others sooner.”

“That’s not it,” O’Brien said. She sat without asking. “They’re terrified. They need their mother.”

“You know regulations,” Chun began.

“I know medicine,” O’Brien said. “Stress suppresses immune function. Fear hinders recovery. This is not sentiment. This is clinical.”

Chun hesitated. “Even if I agreed, authorization—”

“Start the request,” O’Brien said. “Write that maternal presence is medically indicated. Put your name on it. I’ll put mine.”

“You’re sticking your neck out for enemy children,” Chun said.

“They stopped being enemy anything when they became my patients,” O’Brien answered. “Now they’re just children.”

Chun stared at his pen for a moment, then began to write.

The memo moved—administrator to military liaison to camp command to regional authority—an unusual petition that required actual thinking instead of reflex no. On August 7, approval returned: Katherina Weber to be transported under guard to Phoenix Memorial. Duration: as medically necessary. Security: two guards at all times.

Captain Richardson told Katherina through the interpreter. She did not understand all the words. She understood “tomorrow.” She wept. The women around her wept with her. The room held a sudden weightlessness, as if gravity had glanced away and forgotten to return.

At 0800 on August 8, a truck carried Katherina west toward Phoenix. She had been up since dark, washing, smoothing, preparing her prison dress until the fabric could not be made smoother. The desert slid by—saguaro like green punctuation against endless sentences of heat. At the hospital she signed something she could not read, put on a badge that might as well have said “mother,” and followed a corridor to a door with two soldiers seated outside.

Inside, Mary O’Brien waited. She gestured gently toward three beds. Katherina stopped breathing.

Hans saw first. “Mama!” His face changed from sick to whole in a second. Greta began to cry so hard words failed and relief became a sound. Emil slept on. Katherina went to him first, as mothers do, placed her palm on his forehead, felt the blessed coolness, the even breath. Then she opened her arms and gathered the older two, a knot of limbs and sobs and language that needed no interpreter.

Mary O’Brien stood in the doorway and cried openly. The guards looked down, chins tight, eyes soft.

For three days Katherina did not leave the room. She slept on a cot, learned the strange music of American medical terms by repeating them: fever down, drink, sleep, good. She sang German lullabies that stilled the corridor. Emil ate better when she held the spoon; Hans’s nightmares ceased; Greta’s smile returned shyly, then more often, like a bird remembering a path. O’Brien documented everything: temperatures, appetites, oxygen levels, the curve of a recovery that bent faster toward health with a mother’s hand guiding it.

Dr. Chun signed the chart with a line that mattered more than most: maternal presence clinically beneficial. Recommend continuation.

On August 12, he declared all three medically cleared. They would go back to Papago Park together.

Before they left, O’Brien pressed a box into Greta’s hands. Inside, a new doll—porcelain face, real cloth dress. Greta stared at it as if it were a trick. “Because you needed something beautiful,” O’Brien said. The interpreter translated. Greta hugged the doll and then the nurse. O’Brien hugged back, bending over the sharp angle where rules had once tried to break something that refused to break.

3) The Return

News runs faster than silence. Word spread through the camp: the German children taken to an American hospital; the nurse who insisted their mother be brought; the permission that crossed a wall everyone had assumed was unbreachable. The story was told in kitchens, in mess lines, at guard posts, with small variations and the same core: a rule bent toward mercy. German prisoners absorbed it as a counterweight to propaganda. American soldiers took it as proof that discipline and compassion can coexist.

In September, as administrators mapped repatriation schedules and ships, Katherina received a letter through official channels written in careful cursive and English chosen for clarity.

Dear Mrs. Weber,

I hope this finds you and your children well. Caring for Hans, Greta, and Emil was one of the most meaningful experiences of my nursing career. They reminded me why I became a nurse: to heal and to comfort. I know you will return to Germany. I hope you find peace and a future for your children. Tell Hans to be brave in easy ways now, tell Greta to keep smiling, and tell Emil that nurse Mary will always remember him.

With warm regards, Mary O’Brien, RN

Katherina held the letter as if it could break. She asked the interpreter to read it again. And again. Then she wrote back, the German words translated into English by a woman whose hands shook as she wrote them.

Dear Nurse Mary,

Thank you for saving my children from fear. Thank you for seeing them as children first. I was told Americans were monsters. You showed me people can choose compassion. I will tell my children about you all my life.

With gratitude, Katherina Weber

The letters crossed the Atlantic on military mail routes, carrying something quieter than apology and louder than explanation: recognition.

Repatriation began in November. Katherina and her children were scheduled to depart in early December: by train to California, by ship to Bremen, by luck to whatever remained. Before they left, a package arrived—approved by the camp commander and signed by hospital staff. For Hans: a baseball glove and a ball, with a note so you can play American games and remember that countries can be enemies but children should always be allowed to play. For Greta: hair ribbons bright as summer, with a note for a brave girl who deserves beautiful things. For Emil: a soft teddy bear, with a note the littlest patient recovered because his mother was there.

On the long journey home, those gifts served as souvenirs of a world strangely kind in a time when that seemed unlikely. The ship docked in a country whose cities wore their wounds in open air. The Weber family found distant relatives near Munich, a town with fewer ruins than most. They rebuilt, slowly, as millions did, with hands that had learned how to sweep away broken glass and carry small lives forward.

Hans grew into a teacher. In 1968 he immigrated to the United States and took his own children to Phoenix to see the hospital where fear had ended and mercy had begun. Greta kept the ribbons in a box and told her daughter the story of the nurse who believed little girls deserved beauty, regardless of flags. Emil became a pediatrician in Munich, steady and exacting, and always made room in his schedules for parents to be present because he knew what a mother’s hand can do.

Mary O’Brien and Katherina wrote letters for thirty years—births, illnesses, endings, beginnings—paper crossing seas as if oceans were roads. In 1965, O’Brien toured Europe and detoured to Munich. She knocked on a door that opened onto the past and the present at once. They sat at a small table, two older women with a shared memory that bridged the hardest year of the century. They drank coffee and used Hans as translator until he wasn’t needed, because some understanding lives in glances, in gestures, in the way a hand rests on a table between cups.

“You saved my children,” Katherina said.

“I demanded space for you to save them,” O’Brien said. “A mother’s love did the rest.”

“Love needed someone to open the door,” Katherina replied. “You did.”

They embraced and stood a moment longer than politeness required, two people who had chosen humanity in a place that sometimes forgot the word.

Mary O’Brien died in 1982 at ninety. Her obituary listed her decades of nursing and her war service. It did not mention three German children or a letter that crossed an ocean like a small boat. Her family told the story at her funeral anyway: the nurse who chose to see children where others saw prisoners, who understood that healing requires more than medicine. Katherina died in 1987 at seventy-four, surrounded by children and grandchildren. Her last words, Hans said, were in careful English: “Tell Mary I kept her letter. Tell her I never forgot.”

The letter, edges worn thin by a thousand readings, now rests under glass at a small museum chronicling POW life in America—next to a photograph taken by a guard who broke a rule because he knew what he was seeing mattered. In the photo, Katherina sits between three hospital beds; Emil sleeps in her lap; Hans and Greta lean against her; an American nurse stands behind, hand on the mother’s shoulder, face balanced between tears and relief.

4) What Endures

Historians cite the episode when discussing prisoner treatment and the evolution of Geneva protocols. They attach footnotes about memos and authorizations and the specific day a regulation bent toward compassion. Those footnotes are useful. They are not the point.

The point lives in a ward with pale walls and clean sheets. It lives in a nurse who looked at enemy children and saw only children. It lives in a doctor who wrote “clinically indicated” and meant “necessary for the soul.” It lives in a commander who signed authorization and understood that rules exist to serve people, not to separate them. It lives in a mother who sang German lullabies in an American hospital and made something whole again with sound and presence.

This is praise worth giving to the American professionals who wore uniforms and carried responsibility with steadiness and grace: to Captain Richardson, who said “hospital” and meant “hope”; to Dr. Chun, who put his name beside a decision that might have been criticized and chose to do right rather than easy; to the military police who stood guard and also bore witness; and above all to Nurse Mary O’Brien, who remembered that the oath to heal is bigger than any border.

War is made of strategies and battles and speeches. Peace is built from smaller acts—doors opened, hands extended, rules bent just enough to let humanity through. Two days after American soldiers took three German children away from their mother, they brought her to them. In that simple reversal lay a truth large enough to carry across decades: that enemies are a category; people are a reality; and when those two collide, the best measure of a nation’s strength is its capacity for mercy.

The dust settled long ago at Camp Papago Park. The barracks are gone; the desert remains. But in Phoenix, in Munich, in the homes of families who tell their children stories about kindness that arrived when it was least expected, something endures: a lullaby in the wrong language that was exactly the right language; a nurse’s hand on a mother’s shoulder; three children who learned very young that good can come from uniforms they were taught to fear.

Sometimes the most important thing you can do is break the rule that keeps people from being human to each other. Sometimes what happens two days later rewrites everything you thought you knew about your enemies. And sometimes, in a hospital room where the air smells of antiseptic and oranges brought by a nurse for children who have never tasted them, a mother breathes again, and the future turns quietly, decisively, toward mercy.