German POWs Expected NOTHING on Christmas 1944 — American Guards Did Something That Made GROWN MEN

Christmas Behind the Wire (Oklahoma, 1944)

Chapter 1 — Frost on the Barracks

The wind came first, sliding through the pine woods of eastern Oklahoma with a dry, steady voice. It found every loose board and every thin seam of tar paper, and it made Camp Gruber’s barracks complain in small sounds—creaks, rattles, and sighs.

.

.

.

Inside, three hundred German prisoners lay awake in the dark.

In December of 1944, sleep did not arrive easily for men who had learned to listen. In North Africa, listening had meant survival: the distant cough of artillery, the sudden rise of engines, the sharp snap that came a heartbeat before the ground answered. In captivity, listening meant time. It meant knowing whether the guard’s steps were tired or angry, whether the night would stay quiet, whether the world had changed while they waited behind wire.

They had stopped expecting anything from Christmas.

Christmas belonged to another life—one with kitchens and families and candles, a life that had narrowed into memory. Here there were fences, watchtowers, and routines that never cared about dates on a calendar. The war was everywhere and nowhere at once: in the newspapers the guards read, in the rumors that moved from bunk to bunk, in the way letters came rarely and answers came never.

Klaus Becker stared at the ceiling above his bunk. He was twenty-six, captured in Tunisia in May 1943. Eighteen months was long enough to wear down the sharp edges of shock and leave behind something duller, heavier: the slow, grinding knowledge that you could be alive and still be far from living.

He had once believed, as many young soldiers do, that a man could carry his certainty like a weapon. But captivity took that away. The camp did not beat them; it did not starve them. It did something more confusing. It kept them alive. It fed them. It made the sky feel too wide, the meals too steady, and the enemy too ordinary.

Klaus turned his head and saw Hans Müller on the lower bunk across the aisle, eyes open. Hans was a carpenter from Bavaria, captured in Normandy three weeks after D-Day. Next to him, Friedrich Weber—the schoolteacher—lay still as if he had practiced patience for years. Otto Schmidt, a farmer’s son, muttered in his sleep and then fell quiet.

Three hundred men, and each one carried a private inventory: a home, a face, a smell, a street corner, a mother’s hands, a child’s laughter. Each one carried the question they rarely spoke aloud: Is there anything left to return to?

Outside, frost crept along the windows like slow handwriting. Klaus watched it spread and told himself the same thing he told himself every day: want nothing, and disappointment cannot find you.

That night, just before midnight, the camp changed its voice.

Footsteps approached—many of them. Not hurried, not angry. And then, faintly at first, came singing in English. A melody Klaus knew so well it struck him like a hand to the chest.

The barracks lights flickered on.

A guard’s voice called out, rough with cold and uncertainty, and then the doors opened wider. “Raus! Everyone out! Formation!”

Men sat up sharply. Late-night formation meant trouble: an escape attempt, a fight, a punishment, an inspection that would find the smallest excuse to turn life harsher. The prisoners dressed quickly, boots on, coats buttoned, breath white in the air as they filed outside.

Klaus stepped into the cold and saw the camp’s central recreation building glowing as if it held summer inside. Warm light spilled onto the frozen ground. And the singing continued—clearer now, steadier, a choir of American voices.

For a long moment the prisoners stood in loose rows, staring.

It was a strange thing, to be frightened by warmth.

Chapter 2 — The Sergeant’s Decision

Sergeant James Wilson had been in the Army long enough to know what rules were for. He had also been alive long enough to know what they could not do.

At forty-two, Wilson was too old for infantry service. His war was gates and ledgers, counting heads and checking fences, making sure nothing became a headline. He had a wife in Tulsa and three children who wrote him letters in uneven handwriting. He had a mortgage and a quiet sense of responsibility that did not fit neatly into military orders.

He did not see monsters when he looked at the German prisoners. He saw men who were tired, thin in a way the Oklahoma winter could not explain, men who tried not to hope because hope was a kind of hunger.

A few weeks before Christmas, his wife Margaret had asked him a question while she wrapped presents at their kitchen table.

“What will they do for Christmas?” she said, meaning the prisoners.

Wilson had answered without thinking. “Nothing. I suppose we don’t celebrate their holidays.”

Margaret’s hands had stopped. She looked up at him, her face lit by the lamp and by something firmer than light.

“Nothing, James? That’s awful. It’s Christmas.”

“They’re enemy prisoners,” he had said. The words sounded official, safe.

“They’re also men,” she replied, quietly, as if that settled the matter.

Wilson carried her words back to Camp Gruber the way a man carries a stone in his pocket—small, heavy, impossible to ignore. He watched the prisoners more closely after that. He noticed the way they moved through days with mechanical discipline and empty eyes. He noticed how they turned inward when guards approached, protecting the last private territory they had: their thoughts.

He went to Colonel Robert Henderson, the camp commandant, a careful administrator who believed in procedure and disliked surprises.

Henderson listened while Wilson spoke, then removed his glasses and leaned back.

“You want to organize… a Christmas celebration?” the colonel asked. He said it as if he were testing the words for hidden wires.

“Nothing elaborate, sir,” Wilson said. “A tree, maybe some food. A few small gifts. Just… something different from the usual.”

“Why?”

Because it’s the right thing to do, Wilson thought. Because if a nation is strong, it can afford decency. Because cruelty is easy.

He said, “The Geneva Convention requires humane treatment. And humanity doesn’t stop at the fence line. It might improve cooperation. Reduce trouble.”

Henderson studied him for a long time, weighing risks and politics and the kind of criticism that could arrive from people who had never stood guard in the cold.

Finally he said, “Nothing that looks like fraternization. Nothing that compromises security. And it comes from donations, not the Army budget. Clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then do it,” Henderson said, and his voice softened by a fraction. “But keep it quiet.”

Wilson left the office with permission and a problem: turning a moral idea into logistics.

He found help where he could. A few guards grumbled, but some nodded, understanding what he was trying to do. The camp chaplain, Captain Robert Morris, was the first to step forward with enthusiasm.

“People will donate,” Morris said. “They’ll understand if it’s framed as decency, not politics.”

A farmer delivered a tall pine tree. The camp carpenter shop agreed to make wooden ornaments. Soldiers dropped coins into a coffee tin. Margaret Wilson, back in Tulsa, organized wives to bake cookies—hundreds of them—packed into plain tins with no names.

Nothing extravagant. Tobacco. Soap. Writing paper. Chocolate bars. Playing cards. Small comforts that said, without speeches: You are still a person.

As Christmas approached, the prisoners noticed unusual movement: a tree carried into a storage room, guards smiling when they thought no one watched, the mess hall busier than normal.

Rumors spread in German. Red Cross? Exchanges? Policy changes?

Klaus Becker did not join the speculation. Hope was dangerous. He had learned that. Want nothing, he reminded himself.

And then, on December 24th, the lights came back on at 11 p.m., and the guards ordered them outside.

Klaus pulled his coat tight and felt his certainty wobble—not from fear alone, but from the strange feeling that something impossible was about to happen.

Chapter 3 — The Doorway of Light

The prisoners stood shivering in formation, breath rising in pale clouds. Above them the watchtowers remained, dark shapes against the night. The fences were still there. The world had not changed.

And yet the recreation building glowed like a lantern.

Sergeant Wilson stepped forward with Captain Morris beside him. A young private who spoke German stood ready to translate.

Wilson began in English, his voice firm but not harsh. The translator carried it into German with careful, respectful words.

“Gentlemen,” Wilson said, “it’s Christmas Eve. We know you’re far from home. We know this year has been hard—for all of us, though in different ways.”

Klaus watched faces around him tighten, then loosen. Men who had expected punishment found themselves receiving something else: acknowledgment.

Wilson continued. “Tonight, for a few hours, we want to do something different. We want to give you Christmas—not as guards, not as enemies, but as men who understand what it means to miss home.”

The translator’s German fell into the night like warm water.

“You’re invited inside. There’s food. Decorations. Small gifts. No strings attached. No favors expected. Just Christmas.”

Silence held the group. The words did not fit into the prisoners’ understanding of war. They had been taught that the enemy was brutal, that capture meant humiliation. They had prepared themselves for that story. They had lived inside it.

Now the story shifted.

Slowly, as if afraid the ground would change its mind, the prisoners began to move.

The building could not hold all three hundred at once. The guards organized them in groups of fifty, rotating through the night. Klaus’s group waited outside for nearly an hour. He watched men emerge from the doorway with expressions he could not name—shock, wonder, and something tender that looked almost dangerous.

When Klaus finally stepped through the door, warmth struck his face like a memory.

The room had been transformed. Red and green paper chains crossed the ceiling. A Christmas tree stood in the corner, tall and real, decorated with wooden ornaments painted in bright colors. Popcorn strings looped around its branches. A star made of tin foil caught the light and flung it back in small flashes.

Tables along the walls held food that exceeded anything the prisoners had seen in months. Cookies. Cakes. Fruit. Coffee. Chocolate. Not rations measured by policy, but abundance measured by intention.

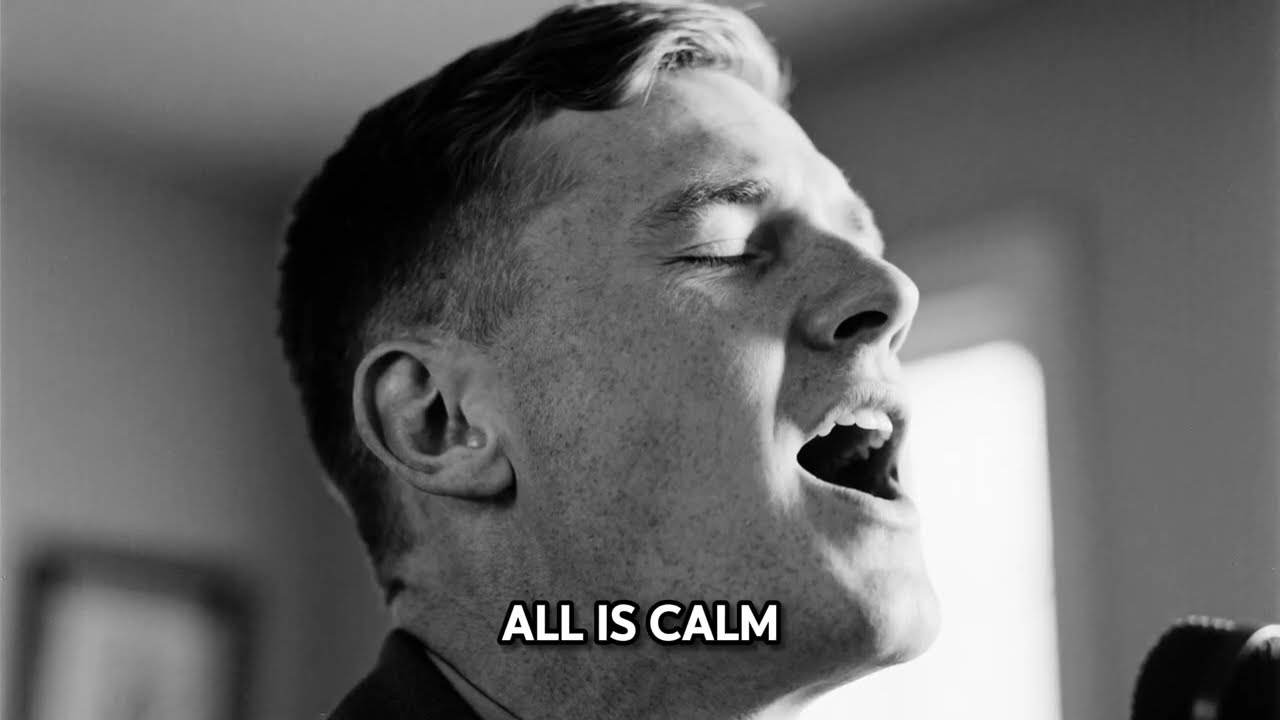

In the center of the room stood a group of American soldiers with songbooks. They began to sing.

“Silent night, holy night…”

The melody was universal. It did not belong to nations. It belonged to winter and candles and human longing.

After the first verse, a German voice joined in, singing the familiar words in German. Another voice followed. Then another. Soon the room filled with two languages braided together, as if the air itself could not separate them.

Klaus felt something break—not his spirit, which war had already bent and rebuilt into survival, but a wall he had built between himself and feeling. A wall that said: They are the enemy, therefore they cannot be human to you.

Enemies did not do this. Enemies did not set up a tree, hang decorations, and sing carols. Enemies did not offer cookies baked by wives in Tulsa.

And yet here they were.

When the singing paused, Captain Morris stepped forward. His voice was calm, his presence steady.

“There are gifts on the tables,” he said, translated into German. “Small things. Take what you want. And there is food—more than enough. You have one hour. Eat. Rest. Remember what it feels like to have Christmas.”

The prisoners moved forward slowly, like men stepping onto thin ice.

Klaus picked up a cookie, hesitated, and bit into it.

Butter. Sugar. Cinnamon.

It tasted like a kitchen. Like someone’s home. Like the world before it became barbed wire and smoke.

His eyes filled without warning. He turned his face slightly, ashamed of the tears, but when he looked around he saw he was not alone. Grown men—soldiers who had marched through deserts and crawled under gunfire—stood crying quietly over cookies and carols.

At the edge of the room, the guards looked away, granting them the dignity of privacy. That small act, too, felt like mercy.

Hans Müller stood near the tree, touching a wooden ornament with careful fingers, recognizing the work of hands like his own. Friedrich Weber read a German carol posted on the wall and his voice broke on words that had once been safe to say. Otto Schmidt ate apple pie with an intensity that suggested he was eating time itself, trying to hold on to something slipping away.

The hour stretched and collapsed, elastic as all meaningful moments are. Klaus sat with a few others, drinking coffee that warmed his hands, speaking softly about Christmases before the war.

“My mother made Stollen every year,” he said. “She started days ahead. The whole house smelled… like this.”

Hans nodded. “The Christmas market in Munich. Roasted almonds. Toys in the stalls. My daughter’s hand in mine.”

They fell quiet. Each man traveled privately to a place he could not reach, carrying the painful uncertainty of whether it still existed.

When the guards announced the next rotation, Klaus stood. He looked back once at the tree glowing in the corner and felt an unfamiliar weight in his chest.

Gratitude.

Not for captivity. Not for war. But for the reminder—sharp and sudden—that humanity could survive even inside the machinery of violence.

Chapter 4 — Morning Without a Miracle, and Yet

By dawn, every one of the three hundred had passed through the warm room.

The decorations remained. The tree stood, slightly askew now, its branches missing a few ornaments the prisoners had been invited to keep. The tables were messier, crumbs scattered like evidence of joy.

The guards were exhausted, but they wore a different kind of tired. It was not the fatigue of duty; it was the fatigue of having witnessed something that had demanded more than procedure. Decency took effort. It required planning, donations, risk, and the courage to look enemies in the face and still see men.

Christmas Day itself returned to routine. Roll call. Work details. The same fence line, the same watchtowers. War did not pause for carols.

But the camp felt altered, as if the air had been adjusted by a degree.

The prisoners moved with slightly less resignation. Their conversations were not brighter, exactly, but freer. They did not suddenly forget what they were. Yet something in them had softened enough to allow speech with guards that did not sound like bargaining or bitterness.

Klaus noticed it in small moments: a guard answering a question without suspicion; a prisoner returning a tool without muttering; a brief nod exchanged at the gate.

Nothing dramatic. No sudden friendship. Regulations remained, and the wire still separated lives. But the constant tension eased, as if both sides had discovered a truth that made cruelty feel unnecessary.

Klaus spent Christmas afternoon writing letters.

He wrote to his mother, though he did not know if she was alive to read it. He wrote to his sister, though he did not know if her house still stood. He described Oklahoma’s pine forests and the cold that crept through barracks walls. He described the Americans—carefully, honestly, as if the words needed to be weighed.

“Last night,” he wrote, “our guards gave us a Christmas tree. Cookies. Carols. For one hour they allowed us to remember we were human.”

He paused, then added, “I do not know what it means for the war. But it changed something in me. I had forgotten that kindness could exist for no reason except that it should.”

He sealed the letters knowing they might never arrive. Still, writing them felt like reaching across a distance that war had made enormous. The act mattered, even if the outcome did not.

In the guard quarters, Sergeant Wilson drank coffee with Captain Morris and a few others who had helped. Their hands were chapped from winter and work. Their eyes were heavy.

One young guard said, “Do you think it mattered? I mean, really mattered? They’re still prisoners. We’re still at war.”

Wilson did not hesitate. “It mattered,” he said. “Maybe not in ways you can count. But it mattered.”

Morris nodded. “When you remind someone they are human, you give them permission to feel again. Of course they cried. What else could they do?”

Wilson stared into his cup. He thought about his wife in Tulsa, about his children opening presents. He thought about the German men crying quietly, and how the tears had looked the same as any tears he’d ever seen.

“I didn’t do it because they deserved it,” Wilson said after a moment, choosing his words. “I did it because we needed to be the kind of people who would do it anyway.”

That was the truth of it. Decency was not a reward. It was an identity.

Chapter 5 — What Kindness Does to War

The weeks after Christmas were still winter. Still war. Still uncertainty.

News came in about the Battle of the Bulge, about men freezing and dying in forests far from Oklahoma. The guards read headlines. The prisoners caught fragments of information and traded them in whispers. The world continued to grind forward.

Yet Camp Gruber became, in its own small way, steadier.

Work details ran smoother. Complaints decreased. There were fewer small fights that sprang from boredom and humiliation. When a camp is full of men who feel invisible, tension rises like steam. When men are seen—truly seen—some of that steam releases.

Klaus found himself speaking to Sergeant Wilson once, briefly, during a work assignment. It was not a deep conversation. It could not be. The rules still existed. The wire still existed.

But Klaus said, in careful English, “Thank you. For Christmas.”

Wilson’s face tightened with something like embarrassment. He glanced around, making sure no superior officer was listening too closely.

“You’re welcome,” he said quietly. “I hope you get home.”

That simple sentence landed in Klaus’s mind and stayed there. Not as promise, not as policy—just as a human wish expressed by a man whose uniform did not erase his ordinary decency.

Klaus began to understand something that felt both comforting and painful: the enemy was not a single thing. The enemy was a government, a strategy, a machine. But the men inside that machine—on both sides—were not machines. They were fathers, sons, carpenters, teachers, farmers. They had all been placed into roles by history and told to behave like categories.

That Christmas night had cracked the category.

It did not absolve anyone of responsibility. It did not erase what the war had done. It did not pretend that suffering could be repaired by cookies and songs. But it reminded men that cruelty was not the only option available to them, even in uniform, even in a time when hatred was easy to justify.

And perhaps that reminder was more powerful than it seemed.

Because war depends on dehumanization. It needs it the way engines need fuel. If the enemy is not human, then anything becomes permissible. If the enemy is only a label, then conscience becomes inconvenient.

For one night in Oklahoma, conscience returned.

Chapter 6 — After the Wire, the Story Remains

Years later, after Germany’s surrender, after the long process of repatriation, Klaus Becker returned to Munich.

He found ruins where streets had been. He found familiar buildings damaged, patched, altered. He found that his mother was alive, thinner than memory but real. He found his sister, hardened by loss yet still standing. Life did what it always does: it continued, even when it had no right to.

In the first months back, he spoke little. Many returned soldiers spoke little. Words were inadequate. Silence felt safer.

But on one winter evening, with candles on a table and the smell of bread in the air, someone asked him about captivity in America.

Klaus hesitated, then told them about Christmas Eve 1944.

He described the cold Oklahoma night. The sudden order to form up. The warm light pouring from a recreation hall. The paper chains. The tree. The carols in English and German woven together like two hands clasped.

He described men crying—proud men, broken men, men who had learned to survive without feeling—crying over cookies baked by women who would never know their names.

“They told us Americans would be brutal,” Klaus said, his voice low. “They told us capture would be only humiliation.”

He paused and looked at his mother’s hands, older now, but still hands that had once baked Stollen.

“But in that camp,” he continued, “we found men who gave us Christmas. They reminded us—enemy soldiers, prisoners—that we were still human.”

The story spread quietly, from mouth to mouth, carried by those who needed to believe something decent had survived the century’s worst years.

Sergeant James Wilson returned to Tulsa in 1945. He went back to his job, his mortgage, his children. He did not come home with medals or dramatic battle stories. When his children asked him about the war, he told them about one night in Oklahoma when he chose, as an American soldier, to represent his country at its best.

He told them that power without restraint was not strength. He told them that rules mattered, but character mattered more. He told them that there were moments in history when the simplest act—offering food, offering song, offering dignity—could push back against the darkness.

“War teaches people to see enemies,” Wilson said, years later, at his own table, his voice steady with the kind of pride that does not need applause. “But we don’t have to forget how to see people.”

And somewhere, in the memories of three hundred men who had expected nothing, that night remained bright. Not as a denial of suffering, but as proof that even in a world built for destruction, someone could still build something else—something gentle, brief, and stubbornly human.