How a Vet Visited a BIGFOOT Daily Since 1980. The Simple Trick That Fooled the FBI – Sasquatch Story

THE QUARANTINE TRICK

A mysterious confession by Dr. Elias Thorne

Chapter 1 — The Day Science Cracked

If you ever dig up the federal case files from the 1996 Cascade sweep, you’ll find my name printed in neat ink—Dr. Elias Thorne, “cooperative witness.” I still laugh at that checkbox. Cooperative. They drank my coffee at my oak kitchen table, scratched my golden retriever behind the ears, and unfolded their topographic maps like they owned the valley. They asked about bear patterns, migration routes, winter dens—quiet questions said by men who believed the world was fully cataloged.

.

.

.

All the while, he was less than fifty yards away, watching them through the slats of my barn, breathing that heavy, wet breath that smells like pine sap and thunderstorms. If he had shifted his weight on the straw, if he had sneezed, if a single board had creaked wrong, the deception would have collapsed. I would have disappeared into a federal cell, and he would have ended up on a stainless-steel table in a lab in Virginia.

To understand how I hid an eight-and-a-half-foot, eight-hundred-pound apex predator in plain sight for decades, you need to understand the time. In 1980 the Cascades were still a place where fog could swallow the noon sun, where the timber thickened into shadows by midafternoon, where silence was a currency and isolation was common enough that nobody questioned it. I was the valley’s large-animal veterinarian—called out at two in the morning for breach births, shot-up hunting dogs, livestock injuries no one wanted reported. I knew every farmer, every logger, every man who lived alone because he couldn’t live with people. I thought I understood anatomy the way a priest understands sin. Then, on a freezing Tuesday in October, my education ended and something older began.

Silas Miller—hard man, iron soul—called me from his radio with a voice that didn’t belong to him. He said he had an animal down near the north ridge. He said it was wrong. When I arrived, the woods were dead silent, as if the valley itself had been told to hold still. The air smelled metallic—wet decay and something sharp, like sulfur after a struck match. Silas stood by his truck with a .30-06 clutched to his chest, staring toward a gully choked with devil’s club and blackberry brambles. “I ain’t going down there, Doc,” he whispered. “I set a bear trap two days ago. Something’s caught. Listen.”

I expected a roar. A shriek. A rage. What I heard was a whimper—low, rhythmic, vibrating—like a child trying not to cry, only magnified through a chest cavity the size of a rain barrel. I told Silas to stay put and started down, medical bag thumping against my hip, boots slipping in mud. The lower I went, the worse the smell became: blood and musk, wet dog turned up tenfold. At the bottom, I saw the trap: rusted iron jaws clamped around a leg that made my mind stutter. Not bear. Not human. A structured ankle joint, tendon thick as rope, hair—not fur—matted with mud and blood.

Then he turned his head.

Time didn’t slow. It stopped. A face evolution forgot. A heavy brow ridge, a high sagittal crest, eyes set deep—amber eyes with whites, wide in shock, bright with comprehension. He looked at the trap, then at me, then back at the trap, and I understood the terrifying truth: he wasn’t a mindless animal reacting to pain. He was thinking.

Chapter 2 — The Needle and the Choice

My hands hovered over my bag while every survival instinct screamed the same word: run. Silas would shoot without hesitation. The sheriff would come. Then the state. Then the men who don’t wear patches. The creature would become a specimen, and I would become a footnote—or a problem to be contained. But the part of me that had spent thirty years reading pain in living bodies saw a patient. A terrified patient hemorrhaging into mud.

I used the tone I reserved for panicked stallions and feral dogs—soft, low, deliberate. “Easy now,” I whispered, avoiding direct eye contact the way you avoid challenging a cougar. His nostrils flared. Steam puffed into the cold. He showed teeth—broad grinders and canines thick as my fingers—but he didn’t lunge. He waited.

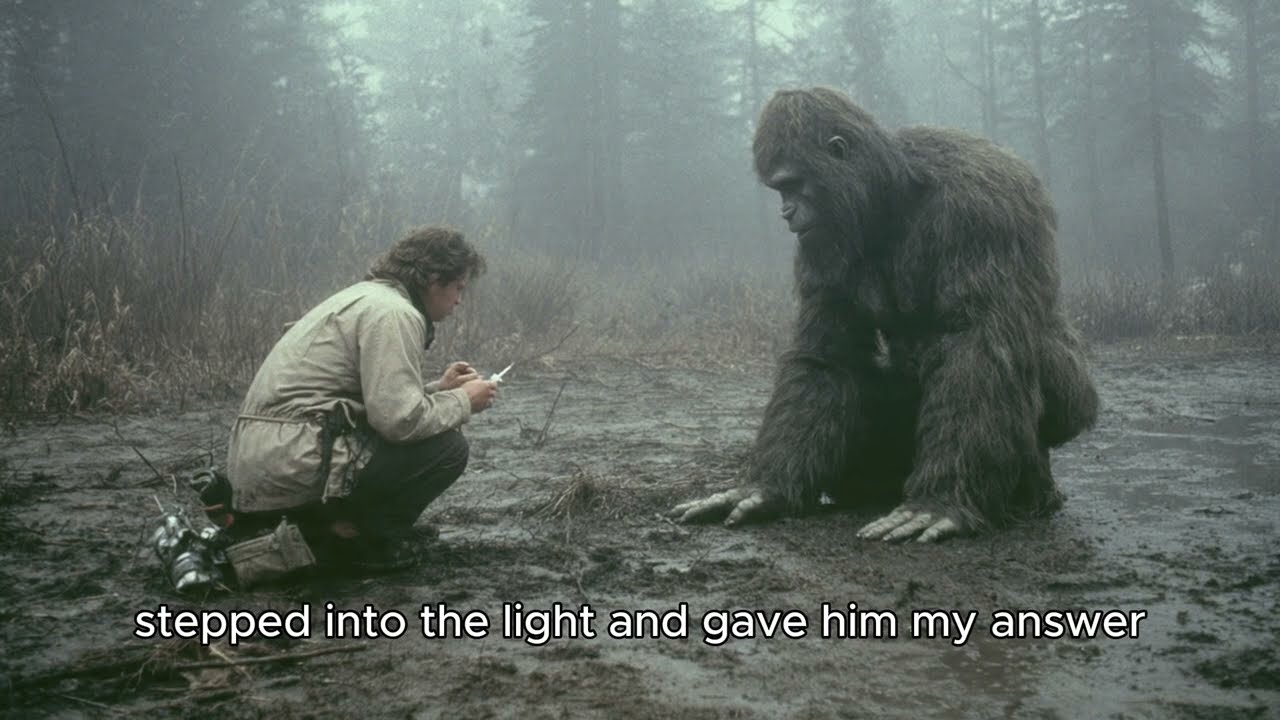

I drew ketamine and xylazine into a syringe meant for boars, enough to drop a draft horse. As I stepped closer, the smell hit me like a wall: pine resin, blood, and something ancient and mineral beneath it. He tracked the needle with an intelligence that chilled me. Then something miraculous happened. He looked at the needle, then at his trapped leg, then back at my face, and his aggression eased by a fraction—as if pain was an equation and he was weighing the variables.

I didn’t have the luxury of hesitation. I lunged forward and drove the needle into the heavy muscle of his shoulder. He roared—betrayal and fury in a sound that shook my rib cage—and thrashed, the chain clanking against the tree. I scrambled backward in mud, heart pounding hard enough to crack bone. But chemistry is honest. His movements slowed. His eyelids drooped. The amber fire dimmed until it became a heavy, drowsy glare. He slumped forward, chin hitting his chest, and the gully went quiet again.

I sat there panting, drenched in sweat despite the cold, and I knew I’d passed the point of return. Up on the ridge, Silas called down, “You alright, Doc?” I looked up through the brush and heard the rifle slide rack. This was the fork in the road—truth or concealment. If Silas came down and saw what I saw, the valley would never sleep again.

“It was a bear,” I shouted, forcing steadiness into my voice. “Big rogue male. Tranquilizer didn’t take. Tore loose and ran off.” A flimsy lie held together by the simple fact that Silas wanted it to be true. After a long pause, he spit and muttered something about damn bears and walked away. The moment his footsteps faded, I turned back to the unconscious giant and did the most dangerous thing I have ever done: I decided to save him, not as a doctor, but as an accomplice.

Chapter 3 — The Winch and the Barn

I had minutes—maybe twenty—before he woke, angry and confused, still bleeding, still strong enough to tear me in half. First, I had to open the trap. I jammed the trap setters onto the rusted springs and pulled until my arms trembled and my shoulders screamed. The jaws yawned open with a reluctant groan. The wound was ugly—deep punctures, exposed pale tissue, bone visible but not pulverized. Fixable, if this were a horse. Fixable, if I had a sterile room. Fixable, if my patient didn’t belong in folklore.

I wrapped pressure bandages tight, noting the thickness of his blood, the speed of clotting, the efficiency of survival written into his body. Then I crawled up the slope, backed my Ford F-250 to the edge of the logging road, and unspooled the steel cable from the winch. Dragging it down into the gully felt like dragging fate behind me. I looped it around his chest, padded it with my jacket so it wouldn’t cut, and engaged the winch.

He slid through mud inch by inch, undignified and heavy, and I guided his head so it wouldn’t smash on rocks. When I finally hauled him onto the road, my hands shook so badly I could barely drop the tailgate. I used planks and leverage and the winch again to load him into the truck bed. He filled it entirely—too long, knees bent, feet braced against the wheel wells. I threw an oil-stained tarp over him and tucked it tight. To anyone passing, it looked like gear. Hay. Logging junk. Ordinary.

The drive home lasted forty minutes and a lifetime. Every bump felt like disaster. I kept checking the mirror, expecting the tarp to rise, expecting a furious hand to punch through the glass and grab my throat. Instead there was only the smell—musk and blood saturating my cab until it felt like I was driving inside a living animal.

My property sat ten miles out, old dairy land with a stone-bottom barn built for cows, heavy oak doors, barred windows. I backed the truck into the barn and shut the doors like a man sealing a coffin. Only then did I lift the tarp. His breathing had changed—faster, shallower. The drugs were wearing off.

I set up field lights. I laid out suture, disinfectant, lidocaine. I threaded a needle, and he moved.

Not a thrash. A low vibration that shuddered through the floorboards. He pushed himself upright, and in that dim barn light he seemed too large to exist. He looked at the tools on the walls, the hay bales, the swinging bulb. Then his amber eyes locked on me. He didn’t roar. He made a high, questioning chirp—birdlike, incongruous—and pointed at his leg, then at me.

A question. Simple. Terrifying.

Are you hurting me, or fixing me?

Chapter 4 — Forty-Two Stitches of Trust

I didn’t have enough ketamine to put him under again. So I did what you do when you have no good options and you’re already in too deep: I relied on the one thing I’d earned in my life—calm hands and a calm voice. I injected lidocaine around the wound edges and watched his muscles ripple beneath hair that moved like wet rope. Every time the needle touched raw flesh, he rumbled low in his chest, a sound like distant thunder rolling under rock. Yet he didn’t pull away. He watched my hands. He watched the thread. He watched the skin draw together.

Forty-two stitches. When I tied the last knot, he exhaled long and heavy, then leaned forward and sniffed the bandage as if memorizing the smell of what had saved him. Then—slowly, carefully—he extended one thick finger and tapped the center of my chest. Not a shove. Not a threat. A gesture that felt like gratitude, delivered in a language older than words.

Saving his life was the easy part. Keeping him alive without exposing him was the nightmare. He needed fifteen to twenty thousand calories a day. I couldn’t buy fifty steaks without becoming the main attraction at the grocery store. So I built a diet out of plausible purchases: sweet feed by the pallet, crates of apples, sacks of dog food I claimed were for boarding. He ate it all. He hated kibble—spit it out like insult. He loved fruit. And, by accident, I learned his weakness: marshmallows. Sugar made him docile when pain flared, and that detail—ridiculous as it sounds—became the hinge my entire secret swung on.

Then came the smell. No creature that size lives politely. The barn began to stink like a zoo. I mucked his waste at three in the morning, buried it deep in the woods, burned incense and told myself it was for flies. I became nocturnal, living by the clock of concealment. And three days after I brought him home, the world came to my driveway in the form of Sheriff Brody.

Silas Miller had told stories at the diner. Tracks like snowshoes. A “monster” in a ravine. Brody was a good man, but good men are still men, and men are curious. He sniffed the air, stared at my barn, and started walking toward the door. My mouth went dry. The creature shifted inside—one heavy foot on wood—and Brody’s head snapped around.

“You got livestock in there, Doc?” he asked.

“Old bull,” I lied. “Ornery.”

He reached for the latch.

The barn door swung open. Sunlight flooded in. Brody stepped inside with his hand on his holster. I followed, ready for catastrophe.

The stall was empty.

I heard a creak overhead and looked up to the loft where the shadows pooled against rafters. Two amber eyes blinked down at me from the gloom. With a freshly bandaged leg, he had climbed twenty feet into the beams and flattened himself against darkness like a spider. Nine hundred pounds of muscle had become invisible.

That was the day I stopped thinking of him as an animal I was hiding. He understood concealment. He understood threat. He understood exactly what a badge represented.

We were partners now, whether I liked it or not.

Chapter 5 — The Protocol and the Price

Winter came hard. Snow piled deep. I opened the barn doors one morning when his leg had healed enough, pointed toward the treeline, and told him he was free. He sniffed the wind, looked at the white expanse, then turned around and sat back down in the straw near the heat lamp. Out there, limping through three feet of snow, he would have been vulnerable. Or maybe loneliness was a chain he didn’t know how to break yet. Either way, the truth settled over me like frost: this wasn’t a rescue mission anymore. It was a sentence.

The first casualty was my life beyond the barn. Sarah—the librarian—had been laughing with me about marriage. Then she began asking why I couldn’t let her inside, why my house smelled wrong, why I spent hours behind locked doors. One February night she dropped the key I’d given her onto my porch railing and told me she couldn’t compete with whatever I was hiding. She waited for me to confess. I watched her taillights vanish because confessing would have killed the only thing I was trying to protect. When I went to the barn afterward, he was awake, holding an apple like a child, and he made a soft comforting sound as I sat in straw and wept for the normal life I’d thrown away.

Years layered on. Near-disasters came in waves: a meter reader wandering too close, a water truck driver reaching for the barn handle, neighbors sniffing the air and laughing about “Doc’s weird experiments.” I leaned into the reputation. I became the strange old vet in the valley, the man you avoid. It was camouflage—social invisibility, the cheapest concealment in the world.

But he grew bored. He tested boundaries. That’s when I developed the protocol. At 3:00 a.m., the dead hour, I opened the back doors and let him slip out into the woods behind my property. He moved with silence that mocked his size, hunted small game, drank at the creek, stretched his limbs under moonlight. He had to be back by 5:30 a.m., before the first logging truck hit the highway. I trained him with a dog whistle pitched above human hearing—one blow meant safe, two meant freeze, three meant come home immediately. It worked for years, until technology changed and the world’s eyes sharpened.

Then came 1996, and the ice storm that broke power lines like bones. I slipped on invisible ice and shattered my hip in my yard, dying slowly in the snow while the generator drowned out my cries. He broke out—ripped the barn door off its hinges—and carried me to my back porch with a gentleness that didn’t fit the word monster. He opened my door with two fingers and set me on my mudroom floor like I was fragile. A paramedic later stared at the too-high smear of mud on the door handle and the tuft of hair caught in the latch. He said nothing. But suspicion is its own kind of signal flare.

Six months later, the black SUVs arrived.

Chapter 6 — Coffee With the Hunters

The convoy rolled into my driveway at 9:00 a.m. sharp: black Suburbans, an animal-control van, men in windbreakers with earpieces and eyes that didn’t blink. The lead agent introduced himself like a verdict—Special Agent Vance—and presented a warrant for an “unlicensed exotic animal.” He expected resistance. I gave him hospitality. “Barn’s open,” I said. “Coffee’s on.”

They swarmed my property with professional efficiency. They kicked open barn doors, shouted clear commands, scanned rafters with thermal scopes. When they found nothing, Vance returned to my porch irritated. “Your barn smells like a primate house,” he said.

“I treat animals,” I replied. “Musk lingers.”

Then he signaled the K9 unit.

That was the moment my pulse went cold. You can fool a man’s eyes. You can even blunt thermal imaging with thick wood and insulation. But you do not fool a dog’s nose. The Belgian Malinois hit the ground, zigzagged, caught scent—and pulled hard toward my driveway. Toward my truck. Toward the rusted livestock trailer hitched to it.

That trailer was the trick. The stupid, obvious trick that worked because it was too mundane for clever men to respect.

The night before, when I’d been warned of the sweep, I hadn’t run him into the woods—that’s what they expected. Helicopters, infrared, tracking teams: the forest was a trap. Instead, I loaded him into the trailer ten feet from my house and ten feet from where their vehicles would park. I lined the floor with rubber mats to dampen sound. I stacked hay bales along the walls to insulate heat from thermal scanners. I signed him freeze—flat palm down—and he curled in the darkness like a boulder made of breath.

Now the dog barked and scratched at the metal.

Vance’s hand drifted toward his holster. “What’s in the trailer, Doctor?”

I stood up and let panic rise into my voice—real enough to be convincing, aimed like a weapon. “Call that dog back,” I snapped. “Do not open it.” I used the one authority I had that federal agents still respected: expertise and liability. “Quarantine,” I said. “I’ve got a prize bull in there with vesicular stomatitis. Highly contagious. If your dog breathes that air, he’ll be dead in three days. If you track that virus onto farms, you’ll crash the cattle industry. You want your name on that?”

Vance stared at the trailer—rusted, ugly, believable. He looked at his handler. He looked at me. He made a decision that wasn’t mercy—it was bureaucracy. “Back the dog off,” he ordered.

The handler hauled the Malinois away, furious barks fading into frustrated whines. They searched woods until sunset, found nothing, and returned covered in burrs and anger. Vance leaned close and whispered, “You’re hiding something.”

“Feeling isn’t evidence,” I said.

They left.

Chapter 7 — The Release

I waited an hour after the last engine noise died, then unlocked the trailer door. A massive shadow unfolded from hay. He stepped out stiff and silent, amber eyes reflecting moonlight, and rested his heavy hand on my shoulder with a pressure that felt like a vow. We had fooled the FBI with rust, hay, and a medical lie.

But we both knew the math had changed. They didn’t need proof to keep coming back. Next time they’d bring better sensors, more dogs, different warrants. My farm—once sanctuary—had become a cage with eyes on it. So at 2:00 a.m., the hour of the wolf, I packed a bag not for myself but for him: apples, the old wool blanket that smelled like smoke, a first aid kit built for impossible anatomy.

We drove north without headlights, my old truck rattling up logging roads until asphalt gave way to rock and the air thinned into alpine cold. At a washed-out dead end where the mountain dropped away into mist-choked forest, I killed the engine and listened to the manifold tick as it cooled. The silence felt final.

I opened the trailer.

Out he stepped—eight and a half feet of life that finally fit the world around him. Against glaciers and endless timber, he looked less like a monster and more like a missing piece returned. He breathed in elk and pine resin and ozone, and his posture changed as if his bones remembered something my barn had tried to erase. When he turned back to me, I saw gratitude and sorrow braided together in his amber eyes.

“You have to go,” I said, voice breaking. “Go high. Stay away from roads. Stay away from men.”

He reached out, touched the tear on my cheek with one rough fingertip—so light it barely bent the skin—then made a low rumbling purr in his chest that vibrated in my bones like comfort. He leaned close for one long moment, as if memorizing my face, then turned and walked toward the treeline with a grace that didn’t match his size. At the edge he looked back once, raised one arm in a silent salute, and stepped into the forest. The branches closed behind him like a curtain drawn.

I drove down the mountain alone with an empty trailer that rattled like grief.

Now I’m old. The barn is gone. The records are ash. And sometimes, late at night, when wind howls off the Pacific, I turn on the radio and listen to static between stations. Every once in a while, I swear I hear it—an impossibly long, mournful call that climbs into a shriek and falls back into a rumble. People say that if they were real, we’d have bones, DNA, bodies. I smile at that, because I know the truth.

They don’t leave bodies. They leave warnings. And they know exactly where to hide: not in some mythical cave, but in the blind spot of human certainty—right where you refuse to look.