“I Don’t Want To Leave” — German Woman POW Broke Down When American Soldier Told Her To Leave

1) The Suitcase and the Open Door (Camp Swift, Texas — June 1946)

The orderly room smelled faintly of floor polish and sun-warmed paper. Outside, Texas light fell across the parade ground in a shimmer, the sky so wide it felt like a kind of mercy. Margaret Hartman stood with a single suitcase at her feet and watched Lieutenant James Morrison check her repatriation papers—one page, then another, his finger sliding down names and numbers with the brisk care of a man who wanted no mistakes.

.

.

.

“The transport leaves in three days,” he said, looking up. “You’ll travel by rail to New York, then embark for Bremerhaven. From there, the Red Cross will direct you to Bremen. Your family is outside the city—Braymond, the file says.”

“Braymond,” she repeated. The word sat strange in her mouth, like a memory she wasn’t sure belonged to her anymore.

Morrison set the papers aside and angled his head toward the open door. Beyond it, Camp Swift stretched across the land the way it always had: long rows of barracks, fences that looked more like boundaries than cages, a water tower against unblemished blue. The year since victory had turned the camp quiet and orderly; even the guards seemed to carry themselves with the loose shoulders of men who might go home soon.

“You can go home now, Miss Hartman,” Morrison said gently.

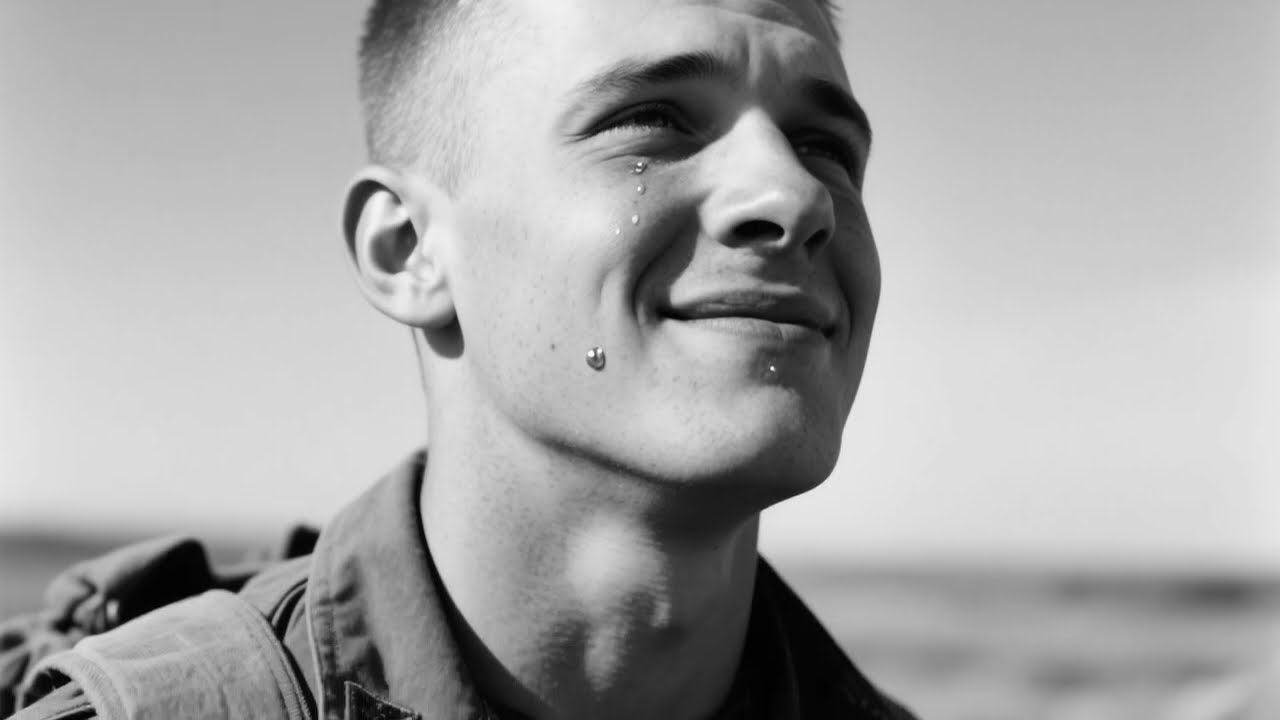

Margaret nodded. Then, to her own embarrassment, she began to cry—not the neat kind of crying useful for sympathy, but the clumsy release that made her cover her face with both hands. The sound that left her throat wasn’t joy. It was grief. Sharp, ungovernable, unexpected.

She cried because home was a word with rubble in it. She cried because leaving meant starting again in a place where even the street names might be gone. She cried because, in the strangest way, she did not want to leave the place that had been a prison and had also taught her how to be a person again.

Morrison waited until she had breath again. “Sit,” he said softly, and slid a chair toward her. “We’ve got time.”

She sat. The suitcase at her feet looked small enough to hold a life that had been simplified to survival; it also looked too small to hold everything she had learned about mercy.

“I thought I would be happy,” she said at last, voice thick. “But I’m afraid.”

“That’s honest,” Morrison replied. “It’s also normal.”

Margaret glanced at the door again. Texas light had its own language. Somewhere beyond it, the laundry building hummed with machinery the way it always had. Somewhere beyond that, Sergeant Hayes was likely explaining something with a patience that had become a kind of refuge. She would need to say goodbye. She would need to be brave enough to get on a train.

“I don’t know how to leave,” she whispered.

“Let’s start with why it’s hard,” Morrison said. “Sometimes naming a thing makes it lighter.”

She tried to name it. Dust, heat, laundry steam, lavender soap at Christmas. A bar of soap that smelled like a world before war. A sergeant who taught her words. An officer who treated repatriation like a blessing instead of an expulsion. A country that had fed her fairly while her homeland starved.

She wasn’t sure where to begin, so she began at the start.

2) The First Arrival (September 1944)

The prisoner train rattled through East Texas under a sun that turned pine forests into bands of lacquered green. Two hundred prisoners shifted on wooden benches—Afrika Korps veterans, U-boat mechanics, Luftwaffe ground crew captured in North Africa and Sicily. In the last car, seventeen women rode in silence, their uniforms bearing the modest insignia of auxiliary service. Margaret pressed her forehead to the glass and watched pine give way to open grassland.

She was twenty-six, educated in Berlin, trained in meteorological observation and radio telegraphy. Her work had been numbers and air—barometric pressure, wind, cloud patterns—encoded and transmitted. She told herself weather was not war, though she knew better. Weather had always been a soldier’s silent accomplice.

She expected barbed wire that felt like claws and guards with jaws clenched. She expected the kind of hatred films had promised.

The train slid into Camp Swift instead.

From the window she saw a military city that had been repurposed: neat rows of barracks with screened windows, mess halls, a recreation yard where men knocked a ball over a net. The guard towers stood, yes, but the soldiers in them looked like men bored enough to be trustworthy. When the doors opened, heat hit like a living thing, and the air tasted of dust and something green.

“Line up,” a sergeant called in halting German. “Women first.”

Separation from the men was efficient rather than cruel. Processing took hours—photographs, fingerprints, a medical exam under the careful hands of a female nurse, then an interview with an intelligence officer who spoke German as if he were born with it.

“Did you encode sensitive communications?” he asked.

“Weather observations only,” Margaret said. “Raw data encoded by protocol. I didn’t see orders.”

He wrote without comment. The questions were not poisonous; they were precise. He dismissed her, and she found herself assigned to a barracks where the windows had no bars, the floors had been scrubbed, and the beds stood in decent rows: seventeen cots, thin mattresses, woolen blankets, enough room for breath.

“It’s better than I expected,” whispered Helga Schneider, thirty-two, a communications specialist who had worked in Italy.

“Better than anything,” said Inge Walter, nineteen, cheeks hollow, eyes too old for her face. “I thought…” She didn’t finish. None of them wanted to speak aloud what they had been taught.

That first night, cicadas screamed in waves. A guard’s boots crunched past their door at slow intervals, not sneaking, not stomping. Somewhere in the camp a radio played an American song with a swing that made Margaret think of a Berlin dance floor she had left behind. She lay beneath a blanket, eyes open, and listened to the hum of electric light and the reliable quiet of a place that did not require fear to maintain order.

She thought of Hamburg and of her mother’s hands in a winter kitchen. She thought of her father’s grave. She thought of weather reports that could guide planes she would never see.

Freedom and captivity existed in new shapes now, and for the first time she could not tell them apart.

3) Laundry and a Photograph

Geneva rules said prisoners could be given work as long as it was not military, as long as it came with pay credited to accounts, as long as it did not humiliate. Camp Swift had work enough to fill a year.

Margaret was assigned to the base hospital laundry. Inside, the air was warm and wet, the machines enormous, the rhythm hypnotic: wash, press, fold; wash, press, fold. She worked alongside three German women and a dozen American enlisted men who treated the linen like a battlefield for cleanliness. The supervisor was a fifty-year-old Texan named Sergeant William Hayes whose gray hair had seen suns stronger than this one and whose quiet made young soldiers respect him before he spoke.

“You’ll sort and fold,” he said in careful German on the first day. “Hospital linens in one line, uniforms in another. Keep things clean, keep them moving. Clean beds help men heal.”

She nodded. The tasks in her hands were small and necessary and did not ask her to lie to herself about their purpose. In that, they felt like redemption.

At noon, she ate under a live oak at the edge of the yard—a sandwich, a mug of water, the kind of stillness that felt like wealth. Hayes sat on a crate and opened his wallet. He took out a photograph and, after a moment’s hesitation, handed it to her.

A woman and two children stood in front of a small house. The children squinted, mid-laugh. The woman looked tired in a way that meant love had been her labor.

“My wife,” Hayes said. “My kids. San Antonio.”

“Beautiful,” Margaret said carefully in English. The word found its target, even with her accent.

He nodded. “They’re why I do this right.”

She blinked. “This?”

“Everything,” he said. Then, as if deciding to trust her with something private: “I served before. I’ve seen what hate without brakes looks like. I’d rather come home to my wife with clean hands.”

That afternoon she folded linen in neat stacks that felt like declarations.

4) Routine as a Kindness

Autumn took the vicious edge off the heat. Work settled into the kind of repetition that freed the mind to remember how to breathe. The women were allowed to receive and send mail—letters arriving weeks late, answers traveling along slow routes like birds who knew where home ought to be. The Red Cross delivered books and knitting wool. A chaplain who spoke German held Sunday services in a converted storage shed and talked not about victory but about peace as a job that lasted longer than war.

In the laundry, language became a bridge. Margaret learned to ask for more twine, to joke about “Texas cold,” to understand the way Americans layered politeness like a quilt over discomfort. Hayes corrected her gently when idioms misled her, and when she got something right he grinned in a way that made the word “teacher” feel accurate.

“Why do you want to learn so fast?” he asked once, not suspicious, only curious.

“Understanding makes things less frightening,” she answered, and he nodded as if that worked for more than language.

Christmas arrived with a bite in the air. Paper chains appeared in the mess hall. Someone scavenged and decorated a tree. The laundry crew worked through the morning then gathered for a few minutes around a cake Hayes swore he had not bartered for (though everyone knew he had). Before the women returned to their barracks, Hayes pressed a small wrapped package into Margaret’s hands.

“From my wife,” he said. “Don’t argue.”

In the barracks, all seventeen women opened identical packages. Inside: a bar of lavender soap and a card in careful English. Merry Christmas. May there be peace soon. The Hayes family, San Antonio, Texas.

Margaret held the soap to her face and inhaled. The scent lifted a childhood afternoon as clean as a page: her mother’s garden, the last spring before rationing, when the lilacs had been obscene in their abundance.

“Why would they do this?” Helga whispered. “We are—”

“Enemies,” someone finished. No one said it angrily. They said it like a word that had lost its teeth.

Margaret wrote her first letter home in months.

Dear Mama, I am safe. I work in a laundry. The guards are kind. Today an American family gave me soap that smells like your garden. I thought I would never smell lavender again.

She did not know if the letter would make it through. She sent it anyway. Some acts you performed because you were human; the outcome did not change the truth of it.

5) War’s End, Work’s Beginning

News came in fragments. By March, rumors turned into bulletins everyone pretended not to read with desperate hunger: the Rhine crossings, cities falling like heavy doors shutting one after another. The maps in the orderly room grew new pins daily.

In May, the announcement came like a weather change a body recognizes before the air moves.

Germany surrendered.

American soldiers stood in small groups, not shouting but smiling with relief like men who had walked out of a burning building. The women sat quietly on their bunks and stared at the floor or at each other. The word “defeat” was inadequate to the feeling; what they felt was the end of an era that had carved itself into their bones. Some wept for what their country had done. Some wept for what had been done to their cities and families. Some wept without reason they could name.

The next morning in the laundry, Margaret folded sheets without seeing them.

“You all right?” Hayes asked.

“No,” she said, and startled herself by telling the truth.

“Sit,” he said, and handed her a chair.

“I served them,” she said after a long silence. “I encoded weather for them. I helped make their war work.”

“You did,” Hayes acknowledged. “And now it’s over. You’ve got years to make something else work.”

“If I have home to go to,” she said.

He squeezed the back of the chair, not her shoulder—careful with boundaries even when kindness was easy. “I’m sorry about that part,” he said. “I lost a brother in France. I hate this war more than I know how to say. But I don’t hate you.”

Her eyes filled again. She had been taught to prepare for hatred like weather; no one had trained her for a mercy that asked nothing in return.

The Pacific war dragged the year longer. Repatriation moved at the pace of bureaucracy and crowded ships—slower than hunger, faster than grief. Camp Swift slipped into a limbo that was not war and not peace, and in that strange in-between, people tried themselves on for size as versions of who they might be next.

Margaret learned she dreaded leaving more than she admitted. Safety had become routine. Routine had become shelter. And shelter had become the one thing she did not want to lose.

6) The Letter and the Fear

In August a miracle arrived: a Red Cross envelope, dirty at the edges, the ink thinned by distance. Margaret recognized her mother’s hand and felt the world tilt under her feet. She opened the letter and read as if the paper might vanish if she took too long.

My dearest Margaret, we are alive. Your sister and I survived in the cellar when the city burned. We have moved to Aunt Hilda’s farm near Bremen. There is food here and safety. Come home when you can. We wait for you. We pray for you. We love you. Mama.

She read the letter five times. Then she walked to the laundry and put it in Hayes’s hands. He read it line by line, mouthing the German as he translated to himself. When he finished, the smile he gave her was bright enough to hurt.

“That’s good,” he said. “It’s better than good.”

“Yes,” she said, and felt terror, too. Home had reassembled itself on paper. Now she would have to walk toward it.

“You’ll be fine,” he said, eyes kind, as if he could lend her belief. “You’re strong.”

She wanted to be.

7) The Day She Said No

On a cool morning in October, Lieutenant Morrison assembled the women in their compound and read a set of orders that held all the music of a closing movement.

“The War Department has authorized immediate repatriation for all female prisoners of war. Ships will depart from New York in stages. Those bound for the British zone first.”

Bremen. That meant her. She would be among the first to leave.

In the days that followed they were issued dresses and coats from Red Cross donations. They sorted their few possessions into a single suitcase: letters, photographs, small books, the sliver of lavender soap wrapped in tissue.

On departure day, the women gathered in the orderly room, suitcases at their feet. Through the window, the sky grew pale along the edges like paper being lit behind a shade.

“Marga-ret Hartman,” Morrison called, eyes scanning documents. “Papers in order. Transport 0800.”

She stepped forward. She held out her hands to take the packet. Then she heard herself say it.

“I don’t want to leave.”

The room went still, as rooms do when they feel history slip under the door.

“Excuse me?” Morrison said.

“I don’t want to leave,” she repeated, the words stronger now for having been said once. “I want to stay here.”

Morrison’s face changed in a way she didn’t know how to read—not anger, not irritation. Something like grief for someone else’s fear.

“Miss Hartman,” he said carefully, “you’re going home.”

“Germany is rubble,” she said. “It is hunger. It is cold. Here I have work. Here I am safe. Here people have been… kind.”

The last word cracked her voice. She sat in a chair without being told. Tears ran without permission.

The other women looked at her with confusion that bordered on envy. Some of them were ready to run all the way to a ruin if it meant a familiar face waited at the end.

Morrison knelt beside her and spoke in a tone she had not expected a year earlier—gentle and firm at once.

“Listen,” he said. “I know it’s frightening. I know you found something here that restored you. But you have a mother and a sister waiting. And Germany needs people like you. People who have seen mercy and will carry it back.”

“I’m only one person,” she whispered.

“One person matters,” he said. “One person telling the truth can be the difference between a rumor and a memory.”

He stood and offered his hand. She took it. He lifted her to her feet like a father would do for a daughter who had fallen on a sidewalk and scraped her knee, and for one absurd second she wanted to laugh at the picture in her head.

“You have ninety minutes,” he said. “Use them. Say goodbye properly. Then get on the truck.”

8) Goodbyes in Mesquite Shade

She went first to the laundry building. The light slanted in the way it always had. The machines were louder than her thoughts. She walked along the folding tables and touched the wood the way one touches an old church pew. Under the live oak outside, the shade made a pattern on the ground she would carry in her mind for years.

Hayes found her there.

“Heard you gave the lieutenant a scare,” he said, no judgment in the words.

“I tried to stay,” she admitted. “For the first time since I was a child I tried to hide from something I feared.”

He pulled a small envelope from his pocket and pressed it into her palm. “My wife wanted you to have this.”

Inside was twenty dollars and a note in careful English. Dear Margaret, use this to help rebuild. May this be the first of many kindnesses you receive in your new life—and may you pass them on. Sarah Hayes.

Margaret swallowed hard. “I don’t know how to thank you.”

“You already did,” Hayes said. “You learned. You worked. You were decent when it would have been easier to harden. Just keep doing that.”

They stood for a moment in the dappled shade, two people who shared a year that would never be simple to explain. He extended his hand. She took it. A soldier and a former enemy shook hands like neighbors.

“Rebuild well,” he said.

“I will try,” she answered.

9) Eastbound

The truck rattled past the water tower, past the fence that had held them inside a bubble of unexpected humanity, past the gate where guards nodded like old acquaintances. Margaret pressed her palm to the window and watched Camp Swift dissolve into light and mesquite dust.

The train rolled east through towns that looked untouched by anything except time. In New Orleans she thought of the first crossing—the fear, the braced body. In New York the harbor opened like a promise, and the ship loomed, full of bunks and seasick hope.

On deck, the Atlantic stretched and stretched. She found herself standing at the rail beside a woman who had shared a barracks wall and years worth of silence.

“Are you afraid?” Margaret asked.

“Yes,” the woman said. “And also ashamed. And also relieved. And also alive.”

Margaret nodded. “We can be all those things, I think.”

They watched the water and did not talk until the sky went to iron.

Bremerhaven looked like a city imagining itself backward from a pile of bones. Twisted cranes rose like broken hands. The formal border between ocean and land had been erased by blast and fire.

The Red Cross sent her inland by truck to a depot where people moved like sleepwalkers. From there, a bicycle took her further, out through flat fields and small villages to a farm whose chimney smoke made her stop and cry on the road because such normal smoke had become a miracle.

The door opened before she could knock. Her mother stood in the frame, older by a war and a lifetime, her face holding together through an act of will that broke the second she spoke the name.

“Margaret.”

The collision in the doorway was clumsy and perfect. Her sister came next, taller now, hair darker, eyes that remembered the child she had been before the sirens.

“You came home,” her mother kept saying, as if the sentence could ward off all other sentences. “You came home.”

“Yes,” Margaret said. It felt like a prayer.

10) What Endures

The winter was a lesson in making do: potatoes and chickens and a garden that had to be coaxed into believing a world existed where seeds still made sense. Margaret wrote three letters—to the Hayes family, to Lieutenant Morrison, to the chaplain. Hayes wrote back in March. Morrison did not. The chaplain sent a short blessing and a psalm.

In 1947, Margaret married a quiet schoolmaster named Carl Weber who knew what it felt like to mistrust silence. In 1949 they moved to Bremen proper, where her English—learned among steam and cotton—bought them bread and rent; she translated for two firms rebuilding trade with America.

They had children, a boy and a girl. She told them true stories and edited others. She told them about a sergeant who believed decency was not a luxury, and about an officer who believed mercy was a national export worth more than boasting. She told them about lavender soap.

“Did you hate the Americans?” her son asked once.

“No,” she said. “I was taught to. But they would not let me.”

“Why did you cry when they said you could go home?” her daughter asked later.

“Because leaving safety is hard,” she answered, “even when safety is a fence.”

In 1965, Margaret and Carl went back. Not to relive anything; to give thanks properly. Camp Swift had been dismantled and repurposed; buildings stood in different places; grass had claimed where fence posts once were. She found the laundry building by instinct and the way the light fell. It had become storage for a cooperative. She pressed her palm to the warm brick and closed her eyes until steam and detergent came back like a ghost you were glad to see.

They drove to San Antonio, knocked on a door framed by bougainvillea. Sarah Hayes opened it and recognized her immediately, as if time could not alter recognition when gratitude had been involved at the beginning.

“You came back,” Sarah whispered.

“I had to,” Margaret said. “To say thank you properly. To tell you the story went where you wanted it to go.”

William Hayes entered the room with the careful steps of an old soldier. His smile was the same. They sat over coffee and traded the gentle currency of years: grandchildren’s names, the harvests of peace, the old sorrow of a brother lost in France that had never gotten smaller but had gotten less sharp.

When they said goodbye, Sarah pressed another bar of lavender soap into Margaret’s hand. “So you remember.”

“I never forgot,” Margaret said.

She lived long enough to watch a wall fall and a country stitch itself back together in a new pattern. After she died in 1997, her son found boxes of letters and photographs carefully saved: Camp Swift from a distance; a laundry crew in front of a row of machines; a Texas sunset written out in a child’s crayon by a daughter who had never seen it.

At her funeral, he read from a letter dated 1970.

You asked me why I cried when they told me I could go home. I think I know now. It was because Camp Swift was the place where I stopped being an enemy and began to be a human being again. Leaving that felt dangerous. But you were right—I needed to carry the story. Mercy is not a small thing. It is a structure that outlasts ruins.

Years later, when families gathered on a patch of Texas ground to remember a camp that no longer existed, Margaret’s daughter stood beside William Hayes’s grandson and looked out across grass.

“My mother said the Americans taught her she was still a person,” she said. “That’s what she brought home.”

The grandson nodded. “My grandfather said the point of treating prisoners well was simple. He wanted the story to go back over the ocean and plant itself in better soil.”

The wind moved the grass. Somewhere beyond the trees, a train’s faint line sounded on the horizon—just enough to make them turn their heads and smile at nothing in particular.

The story had crossed and recrossed the ocean for decades. It had changed as it passed through mouths and hands, the way all true stories do, becoming simpler and therefore more useful.

It went like this:

In a time when cruelty could have been a currency worth boasting about, American soldiers at a camp in Texas chose something better. They followed rules because rules prevented chaos. But they also chose grace when grace was not required. They stood between shame and the people who had to carry it and said, We will not add to your load.

They taught a woman to fold linen well and to say please in a language not her own. They gave her soap. They gave her back the knowledge that she had a self beyond a uniform. Then they sent her home when she was afraid to go, not because they were rid of her, but because they believed her country needed what she would bring.

That is not a grand strategy. That is not a doctrine. That is the quiet work of decent people.

And in the counting of victory—the kind that matters beyond maps and dates—that is how the balance may finally have tipped: not only because of guns and ships and courage in battle, but because of the American habit, at our best, of understanding strength as something that makes room for mercy.

Margaret climbed into a truck, pressed her hand to the glass, and left Camp Swift behind. She carried the lavender soap and the letter and the image of a live oak’s shade. She carried a sentence she would say to her children and their children whenever the world’s shadows lengthened:

We are always choosing.

She did not always choose perfectly. No one did. But on the days it mattered most—those hinge days when the future rests its weight on your small decisions—she remembered a sergeant’s steady voice and an officer’s quiet patience, and she chose as they had chosen.

That is how a life becomes a bridge.

That is how mercy outlasts war.