My Grandpa Fought a DOGMAN in 1954. He Never Spoke About It, Until His Final Night…

The Journal of Shadows

My grandfather died three weeks ago. But before he took his last breath, he grabbed my hand and told me something that made my blood run cold—something he’d been hiding for seventy years. Something about what really happened to him in the woods in 1954.

.

.

.

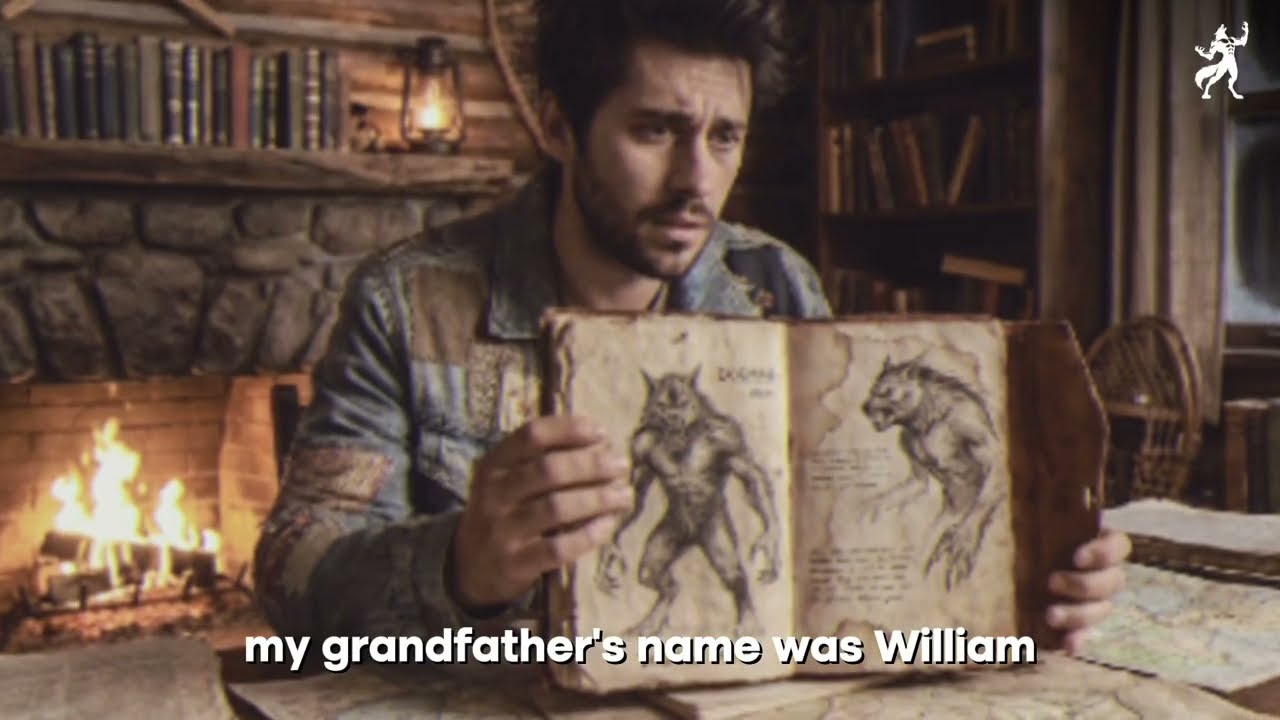

Right now, I’m standing in his old house, holding a battered journal he left me. Inside are details of an encounter that shouldn’t be possible. An attack that left him scarred for life, and a secret so dangerous he made me promise never to speak his real name. For seventy years, my grandfather lived with this burden. Now it’s mine to carry. And after you hear what I’m about to tell you, you’ll understand why some secrets are kept buried.

The Summer of 1954

My grandfather—let’s call him William—was born in 1936. In the summer of 1954, he was eighteen, living in a small logging town on the edge of Michigan’s Huron National Forest. The kind of place where the forest was both a source of life and something to be respected—or feared.

William was strong, six feet tall, broad-shouldered, the kind of young man who could swing an axe all day. His father ran a logging operation, and William had been working alongside him since he was twelve. By eighteen, he knew those woods better than most men twice his age. Or so he thought.

That summer was unbearably hot, the kind of heat that makes the forest feel thick and suffocating, where the air doesn’t move and everything smells like pine needles and decay. William’s father sent him and two other workers—Tommy Brelin and Frank Kowalski—to mark trees in a section of forest eight miles from town. It was supposed to be a three-day job. They’d camp out, mark the trees, and come back. Simple work.

Tommy was twenty-two, married with a baby on the way. Frank was older, maybe forty, quiet, a World War II veteran. The three of them set out on a Tuesday morning in late July, packs loaded, axes strapped to their backs, rifles slung over their shoulders for bears.

They reached their campsite by early afternoon. It was a clearing near a stream—a spot William had camped at before. They set up tents, built a fire pit, and spent the day scouting and marking trees. Everything was normal. The forest was alive with the usual sounds. But that night, something changed.

The Silence

William wrote in his journal that the forest went quiet around sunset. Not gradually, but all at once. One moment there were crickets and night birds. The next, nothing. Complete silence.

Frank noticed first. He was sitting by the fire, smoking, when he suddenly stood up and stared into the darkness. “Something’s off,” he said, but didn’t elaborate. They stayed up later than usual, keeping the fire high, trying to shake the uneasy feeling.

Around eleven, they turned in. Tommy and Frank took one tent, William the other. He remembered lying in his sleeping bag, listening to the silence, feeling like the forest itself was holding its breath. He must have dozed off, because the next thing he knew, he was jolted awake by screaming—not human, but animal. High-pitched and guttural, like a dog and a mountain lion being tortured at once. The sound came from everywhere.

William scrambled out of his tent. The fire had died to embers. Tommy and Frank were already outside, weapons in hand. All three stood in the dim glow, trying to figure out where the sound had come from. Then they heard it again, closer, and with it came a smell—rotting meat, wet dog, and something chemically wrong. A smell that made your body want to run before your mind could process why.

Frank said they needed to get the fire going. They scrambled to add wood, and within minutes, flames leapt three feet high. The light pushed back the darkness, creating a fragile circle of safety—or so they hoped.

For the next hour, nothing happened. The smell lingered but faded. Tommy suggested it was just a bear or wolves passing through. Frank didn’t respond. He just stared into the darkness, jaw clenched. William was about to suggest they take turns keeping watch when he saw it.

The Attack

At first, William thought his eyes were playing tricks on him. Something was moving between the trees, just beyond the firelight. Something big, bigger than a bear, standing upright, moving from tree to tree with deliberate caution. Not like an animal—like something thinking, planning, watching.

He pointed. The others saw it, too. Frank raised his rifle, but before he could fire, the thing moved—toward them, not away. It came faster than anything that size should move. William said it was at least seven feet tall, covered in dark, matted fur. The head was too large, too elongated. The snout was wolf-like, but the eyes reflected the firelight with an intelligence that made William’s stomach drop. It moved on two legs like a man, but with a hunched, predatory posture. Its arms were too long, ending in hands with visible claws. When it opened its mouth, William saw rows of teeth that belonged in a nightmare.

Frank fired. The creature flinched but didn’t fall. It snarled—a sound so deep and vicious William felt it in his chest—then charged.

Everything happened fast. The creature covered the distance in seconds. Frank got off another shot before it was on him. It grabbed Frank with one massive clawed hand, lifted him off the ground like he weighed nothing. Frank screamed. The creature shook him once—bones snapped—and threw him aside like a rag doll. He crashed into a tree and didn’t move.

Tommy fired his rifle, shot after shot, but the creature seemed barely affected. It turned toward Tommy. William’s survival instinct kicked in. He ran—not away, but toward the creature, axe in hand. He swung with everything he had. The blade bit deep into its shoulder. The thing roared, spun toward him, and William saw its face up close for the first time: a wolf’s snout, but wrong, almost human underneath, yellow-green eyes full of rage and intelligence.

It backhanded William across the face. He flew backward, hit the ground hard, axe flying from his grip. Through blurred eyes, he saw the creature advance on Tommy, who was still shooting, still screaming for help that wouldn’t come. The creature grabbed Tommy’s rifle and crushed it in its hand. Then it grabbed Tommy himself.

William staggered to his feet, dizzy, disoriented. He saw his rifle near the fire, grabbed it, turned, and fired. The bullet hit the creature in the side. It dropped Tommy and turned toward William. Blood matted its fur, but it was still coming. William fired until the rifle clicked empty. The creature was ten feet away, bleeding, breathing heavily, but still standing. It looked at William, and he was certain he was about to die.

Then, for reasons William never understood, it turned away. Limping, it retreated to the tree line, stopped, looked back, and disappeared into the darkness.

Aftermath

William ran to Frank. He was dead, neck broken, body twisted. Tommy was alive, barely, with a broken arm, ribs, and deep claw marks. William dragged him to the fire, bandaged his wounds, and kept watch the rest of the night.

When dawn broke, William found the camp torn apart, blood everywhere—human and otherwise. He found massive tracks, like a wolf’s but bigger, with a stride that suggested bipedal movement. He followed the blood trail into the forest, but it vanished in the rocks.

He helped Tommy back to town. They told the doctor it was a bear attack. The sheriff organized a search party. When they returned to the camp, Frank’s body was gone. The official report listed Frank as killed by a bear, body taken by wildlife. Tommy never spoke about what happened. He moved to California, never returned. William tried to move on, but the encounter changed him. He left the woods, worked in town, married, raised a family, but the nightmares never left.

The Weight of Secrecy

William told his wife, Dorothy, the truth once. She listened, held his hand, and said trauma could make people remember things differently. He never brought it up again. He kept the secret locked away, but it never left him.

For decades, William documented his nightmares, the guilt, the fear that the creature was still out there. He searched for similar stories. He found hundreds—people across the country reporting encounters with upright, wolf-like creatures. “Dogman,” some called them. Reading these accounts gave William comfort—he wasn’t crazy—but also reinforced his fear.

He mapped sightings, noted patterns. Most occurred in July and August, in remote forests, often near logging operations. He theorized the creatures were being displaced, forced into contact with humans as their habitat shrank.

He documented his own scars, the hearing loss, the paranoia. He wrote about the three times he thought he’d been tracked or watched in the years since—camping trips cut short, something crossing the road at night, tracks behind his house. He collected evidence—photos of tracks, sketches of the creature, detailed notes.

The Final Confession

In early 2024, William was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer. He declined treatment, said he’d lived long enough. During his final months, he became more withdrawn, but also more open about the past. Three weeks before he died, he asked me to come alone. He told me everything—about the attack, the creature, the decades of secrecy. He handed me his journal, made me promise to read it, to decide for myself whether to share his story.

He said some truths are too dangerous to tell. People aren’t ready to accept that there are things in the woods smarter and stronger than us. Going public would have put a target on his back, and accomplished nothing but making him look insane. But at the end, he wanted someone to know. He wanted the truth preserved.

William died peacefully, surrounded by family. At his funeral, I met Tommy’s brother, who confirmed that Tommy had told him the truth years ago. He’d found disturbing sketches among Tommy’s things after he died—drawings of the creature. He asked if I had any proof. I lied, said I didn’t. He gave me his contact info anyway.

The Journal

I spent days reading William’s journal. The detail was staggering—dates, times, locations, physical descriptions, behavioral observations, maps, sketches. The creature he drew had a wolf-like head, but the proportions were off, the skull too large, the eyes forward-facing, the body humanoid but covered in fur, hands with five fingers ending in claws. The legs were digitigrade, like a dog’s, explaining its speed and gait.

William analyzed the attack: the creature’s reconnaissance, its tactical thinking, its choice to attack at night, its decision to retreat when wounded. He documented the sounds, the smell, the patterns in sightings. He researched local legends—Ojibwe and Odawa stories of shape-shifters, French trappers’ lugarou, German settlers’ wolf-men. He found newspaper articles about logging camps destroyed, men missing, bodies never recovered.

He tracked modern sightings, noting clusters near logging operations, theorizing the creatures were being displaced. He documented his own psychological symptoms—nightmares, hypervigilance, PTSD before it had a name.

Legacy

In his final entries, William wrote about regret—about isolating himself, not finding others, not documenting more evidence, not telling Frank’s family the truth. He wrote about respect for the creature, about the mercy it showed, about the arrogance of humans who refuse to admit we’re not alone.

“If you’re reading this, I’m gone. Tell my story or don’t. I’ve made my peace. But remember—the world is stranger and more wonderful than we admit. Some secrets are kept not to hide the truth, but to protect it.”

The Burden

I’ve joined forums, spoken to other witnesses, heard stories that echo William’s. There’s a hidden community—people who know, but stay silent to avoid ridicule or worse. Some researchers believe the government knows, and keeps it quiet to avoid panic, protect the timber industry, or prevent ecological chaos.

I’ve visited the site of William’s attack, set up trail cameras, documented strange tracks and sounds. I haven’t seen the creature, but I believe it’s out there—rare, elusive, smarter than we want to admit.

So what do we do with this knowledge? Demand recognition? Organize expeditions? Or respect their territory and leave them alone? I don’t have answers. But I know William’s story needed to be told. Frank Kowalski’s death needed to be acknowledged. And the thousands of witnesses out there deserve to be heard.

The Truth

William was an ordinary man who experienced something extraordinary and spent his life trying to understand it. His journal represents not fear, but curiosity. Not denial, but acceptance. Not cowardice, but a quiet, persistent bravery.

His story is now part of the record. If you’ve had a similar experience, you’re not alone. There’s a community out there. And if you ever find yourself in the deep woods, hear that unnatural screaming, or smell that terrible odor—don’t investigate. Just leave. Some things in the woods are better left alone.

Thank you for listening. The forest is bigger and stranger than we like to think. Respect it. Be aware. And remember: some secrets are kept not to hide the truth, but to protect it.