My Thermal Camera Spotted Bigfoot Right Before It Saved Me From a Shocking Attack – Sasquatch Story

THREE KNOCKS IN THE RAIN

A confession from the Blue Ridge backcountry

Chapter 1 — The Heat-Signature at the Treeline

Late October of 2019, deep in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina, I was sixty-seven and living alone in a cabin I’d built three decades earlier. The place sat two miles up a gravel road that washed out every spring, hemmed in by white oak and hemlock so thick you couldn’t see your neighbors’ smoke even if they wanted you to. I had two dogs that slept light, a thermal camera I’d bought on a whim, and a ’67 Mustang in the garage that I’d spent fifteen years restoring bolt by stubborn bolt. My wife had been gone since ’89, and the cabin had turned into more than shelter; it was a boundary line between me and the noise of the world. Out here the sounds were simple—wind through needles, rain on tin, the occasional truck grinding up the mountain like it had a grudge to settle.

.

.

.

The camera had been an impulse purchase that summer. Coyotes were creeping closer at night, and I wanted to know what was moving beyond the porch light. I mounted the thermal on the porch rail, aimed at the treeline about sixty yards out, then forgot about it the way you forget about a lock once you start trusting it. For months the monitor showed me exactly what I expected: deer drifting like pale ghosts, raccoons waddling with hot little hands, once a black bear ambling through at two in the morning like it owned the woods. Nothing unusual. Nothing that made my palms sweat when I reviewed footage with coffee in hand.

Then came the night the rain started and the temperature dropped to thirty-eight. I was half asleep in my chair by the stove when the monitor changed. A bright smear of orange-yellow appeared at the edge of the frame, then solidified into a shape that made the hair on my arms rise. It was built like a man but too tall, too broad, standing just beyond the treeline where the world became black. It didn’t move like an animal. It stood upright, weight shifting subtly from one leg to the other, the way a person stands when they’re waiting—patient, unhurried, as if time belonged to it.

I watched it for eleven minutes. Eleven minutes in which my mind tried to be reasonable: a lost hiker, a neighbor cutting through, a thief casing my place because somebody in town had heard about the Mustang. But hikers don’t stand motionless in cold rain. And thieves don’t stand seven feet tall. When I rose and went to the window, I saw nothing but darkness and rain, yet on the monitor the shape held steady. Then, just as my hand was reaching for the rifle, it turned and walked back into the woods. Not startled. Not hurried. Smooth, deliberate, like a decision already made. And then it was gone.

Chapter 2 — Prints in Cold Mud

The next morning I walked the treeline with both dogs, two mutts that knew the woods better than most people know their own kitchens. They trotted ahead, then slowed, ears angling back as if the forest had leaned close to whisper something they didn’t like. I followed the spot where the heat signature had stood, looking for anything that would anchor my fear to a rational explanation—broken branches, cigarette butts, bootprints, the sloppy evidence of human trespass. What I found made my stomach sink into my boots.

In the mud near a fallen hemlock were prints—barefoot prints, if you could call them that. Each one was about fifteen inches long and seven wide, five toes pressed clear as a stamp, the heel sunk deep enough to hold water like a shallow bowl. The stride between them was longer than mine by a lot, four and a half feet, maybe more. I knelt, traced the edge of one print with my finger. The mud was cold and sticky, and the depth told me weight—three hundred pounds or more, maybe far more if the ground had been firm. One dog whined softly, tail low. The other sniffed and backed away, as if the scent itself had teeth.

I didn’t want to think the word. I’d heard stories growing up in these mountains—things that knocked on trees, things that left tracks and took livestock, shapes moving through fog where no man ought to be. My grandfather told those tales with the calm certainty of someone who’d seen more than he admitted. He’d talk about a smell like wet fur and rot, about voices that weren’t voices, about the way the forest could go quiet as if it was listening too. I’d filed it all away as mountain folklore. Bears got blamed for a lot. So did drunks and bored imaginations. Yet there I was, staring at prints that did not belong to any bear I’d ever seen.

I took photos and measured the prints with a tape measure from the cabin. Then I did something I still can’t fully explain: I covered them. Found a piece of plywood and weighed it down with rocks, like hiding them would keep the truth from spreading. That afternoon I called the ranger station—not about the prints, not about the thermal footage—just a casual question about trespassers, illegal campers, anything unusual. Carla, a ranger I’d spoken to a few times, said it had been quiet. Hunting season wasn’t in full swing yet. Most folks stayed closer to the roads. I thanked her and hung up feeling foolish, like I’d asked permission to be afraid.

Chapter 3 — Three Knocks and the Smell of Rot

The dogs wouldn’t settle that night. They paced the cabin, growled at windows, barked at sounds I couldn’t hear. I sat in my chair with the rifle across my lap, watching the thermal monitor like it was a confession booth. Around ten, the knocks started—three of them, slow and deliberate, echoing through the trees from the south side of the cabin. They weren’t branch cracks. They weren’t an animal scratching bark. They were spaced evenly, each one landing five seconds apart like a measured heartbeat: knock… knock… knock.

My dogs went silent. Not calm—frozen. They stood rigid, staring at the door with their ears forward, as if whatever was out there had become the only fact that mattered. I waited with my breath held. The rain had stopped. The wind had died. The forest went so quiet the cabin creaks sounded loud.

When I opened the door and stepped onto the porch, the motion light snapped on, flooding the yard with harsh white glare. Nothing moved. The treeline stayed dark beyond the light’s reach. Then the smell hit me—wet fur, decay, something organic and overwhelming, like a dead animal left too long in heat and then soaked in rain. The stink rolled over me in a wave so thick I stepped back and covered my nose with my sleeve. The dogs whined and retreated from the threshold like the air itself had struck them.

I stood there two minutes, scanning darkness, listening, trying to separate fear from fact. The smell faded slowly, carried away by a breeze I could barely feel. There were no more knocks that night. But the message remained, lodged under my skin: something was close enough to make itself heard, and close enough to make itself smelled.

Over the next week the knocks returned every few nights, always three, always deliberate, sometimes from different directions, once from directly behind the cabin so close I felt the vibration in the walls. I reviewed thermal footage frame by frame. On the fourth night I caught a heat signature sliding along the northern treeline, passing through the frame in less than ten seconds—upright, broad-shouldered, long-striding. I saved the clip, backed it up, and told myself I was being smart, not obsessed.

Then the small signs began. A stack of smooth river stones appeared on a stump near my woodpile, arranged in a neat pyramid about two feet high. I hadn’t stacked them. Some were creek rocks from a mile down the mountain. A woven circle of grapevine hung from a low branch near the trail to my spring, fresh and green, suspended at perfect eye level like it wanted to be noticed. These weren’t accidents. They were markers. Messages. And the more they appeared, the more I felt watched—even in daylight, even while I worked in the garage.

My grandfather’s stories crawled out of their dusty box in my memory. He used to say that some things in the woods didn’t sneak. They announced. They left signs when they wanted you to understand the rules of the place. Not always as a threat—sometimes as a boundary, sometimes as a warning, sometimes as a strange kind of introduction.

Chapter 4 — The Camera That Stared Back

I drove into town and bought more ammo, batteries, and a motion-activated trail camera from the hardware store. The kid behind the counter asked if I was gearing up for hunting season. I said yes because it was easier than saying, I think I’m being visited by something older than the road you drive on. I mounted the trail camera thirty yards from the cabin, aimed at the spot where the thermal shape liked to linger.

By Sunday night it had recorded forty-three clips: deer, raccoons, a fox, and one video that turned my throat dry. Time stamp: 2:47 a.m. The frame was washed in infrared, grainy and high-contrast. At first I thought the camera had malfunctioned. Then I saw the eyes—two bright points reflecting the IR light, positioned about seven feet off the ground. They stared straight into the lens for three seconds, unblinking, as if the thing behind them understood exactly what a camera was and didn’t care. Then the shape moved out of frame so fast it felt like a visual trick. I replayed it until the file seemed to burn itself into my brain.

That night I sat by the window with the rifle and watched the treeline under a near-full moon. I didn’t see the shape. I saw only darkness and branches and the slow drift of clouds. Around dusk, two men came up my driveway with flashlights, calling out like they owned the right to do so. One was tall and careful, the other shorter with a scraggly beard. They stopped near the garage and asked about the Mustang, about whether I’d sell. Their tone was polite but wrong, like a test.

“It’s not for sale,” I said. “And this is private property.” They lingered anyway, eyes flicking between the rifle and the house, measuring. Then the tall one shrugged and they left, flashlights bobbing down the drive. I watched them disappear with the sour certainty that they weren’t done.

Around midnight, the knocks came again—three, louder this time, from the south. The dogs barked. I moved to the window and saw flashlights in the trees: the same two men, whispering, creeping closer. I thought about calling the sheriff, but the nearest deputy was thirty minutes away on a good night, and these roads didn’t do “good nights.” By the time help arrived, the men could be gone—or inside.

I stepped onto the porch with the rifle raised and shouted into the dark, telling them to leave, telling them I’d call the law. Their lights stilled. One clicked off. Then the knocks came again—three, closer, from just beyond the treeline, so near the sound felt like it pressed against my ribs.

The men’s voices changed. Confusion sharpened them. “What the hell was that?” one hissed. Branches snapped at a height that wasn’t human. Heavy footsteps moved fast without running, deliberate as a decision.

Chapter 5 — The Shape at the Edge of Light

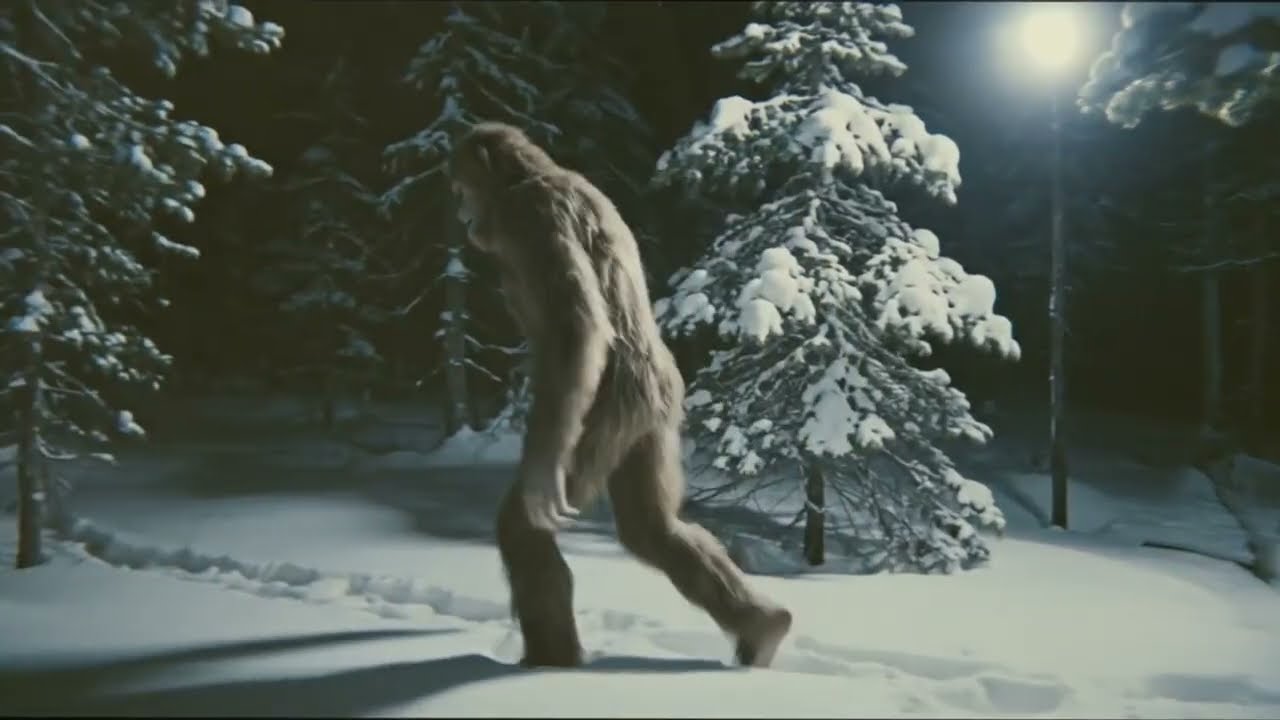

It emerged where the porch light died—just at the boundary of illumination, where the world turns from known to guesswork. Tall. Massive. Covered in dark hair that seemed to drink the light rather than reflect it. It stood upright, easily seven and a half feet, shoulders wider than any man’s, arms long enough that the hands hovered near the knees. It didn’t thrash or posture like a bear. It simply arrived, like the forest had decided to stand up and show its outline.

The two men froze. One made a sound between a gasp and a swear. Then they ran—crashing through brush, tripping over roots, flashlights bouncing wildly as they fled down my driveway like the devil had rented the place behind them. The shape didn’t chase. It didn’t need to. It held the edge of the light as if the boundary itself belonged to it.

Then it turned its head and looked at me. I couldn’t see the details of its face—only bulk and silhouette, the slow lift of its chest as it breathed. But the way it stood was calm in a way that made my skin prickle. Not predator calm. Not threat calm. Something else: certainty. Authority. The kind of stillness you see in old men who have outlived fear.

We stood there for fifteen seconds, and it made a low humming sound—deep, resonant, not aggressive, almost like an acknowledgment. Then it turned and walked back into the trees with the same unhurried deliberation I’d seen on the thermal footage. Heavy steps fading. Darkness swallowing it whole.

My dogs stopped barking and stared at the place it had stood as if they could still see it. I went inside, locked the door, and sat down with my hands shaking. I’d just watched something drive off thieves without laying a hand on them. And it had looked at me afterward not like prey, not like enemy, but like a neighbor considering whether the arrangement was acceptable.

At dawn I found prints where it had stood: deep impressions in soft earth, fifteen inches long, sunk three inches into the mud. The stride was enormous, five feet between steps. I followed the tracks until they vanished on rock, and I said the word out loud for the first time, even though it felt childish on my tongue. “Bigfoot.” Saying it didn’t make it less real. It made it heavier.

Chapter 6 — Gifts on the Stump

That afternoon I went to town and bought apples and jerky. I didn’t know what it ate, but the gesture mattered. That night I set the food on the stump by my woodpile—the same stump where the river stones had appeared—and went back inside without a note, without a speech. Around ten I checked the monitor. The food was gone. In its place sat a fresh pyramid of river stones, stacked neat as a promise.

I smiled for the first time in days. Not because I felt safe in a normal way, but because I felt understood. Something out there had answered my gesture with one of its own. The knocks came less often after that, maybe once every few nights, always three, always the same measured rhythm. I started to hear them not as threats but as a kind of check-in: I’m here. The boundary holds. You’re still under the trees.

I kept leaving food—apples, bread, dried meat. In return I found feathers, woven grass, once a small carved piece of wood shaped like a bird, smooth from handling. I didn’t see it clearly again for a while, but I caught heat signatures drifting through the trees at night, always at a distance, always angled toward my cabin like someone pausing in the dark to make sure a porch light is still burning.

My dogs changed, too. They still barked at the knocks, but it sounded different—alert, not terrified. Sometimes they’d wag their tails and trot to the door like they were greeting a familiar visitor they didn’t want too close.

When the first real snow came in mid-November, I stepped onto the porch at dawn and saw the trail of prints leading from the forest to the stump and back into the trees. Big, clean impressions in untouched white. I stood there with coffee in my hand and a strange peace in my chest. I had chosen solitude for years, but the woods had quietly revised that choice without asking permission.

Chapter 7 — The Daylight Neighbor

Late December brought an ice storm that broke branches and dropped an oak across my woodpile, blocking the path to my spring. I stood there looking at it, thinking about how long it would take my old back to clear it, when I heard movement and turned.

It stood at the edge of the clearing in full daylight, forty yards away. The sight of it in sunlight hit differently than any thermal clip. It was massive—eight feet at least—dark hair thick and matted, face flatter than a man’s, broad nose, deep-set eyes that didn’t look empty or wild. They looked aware. Watching me with a calm intelligence that made my throat tighten. I felt no fear, only awe and a quiet gratitude so sharp it hurt.

It raised one hand and gestured toward the fallen oak, then turned and walked into the trees. A moment later I heard wood crack and branches break. I followed the sound and found it working—dragging limbs aside, clearing a path with methodical efficiency, moving logs I couldn’t have budged alone. I grabbed my axe and helped. We worked side by side for twenty minutes without a word. It never looked at me directly, yet I could feel its awareness like heat on skin. When the path was clear, it straightened, looked at me once, and made that low humming sound again—an acknowledgment that settled deep in my chest like a vow.

Then it walked back into the forest and vanished.

I went inside and cried by the fire, not from fear, not even from loneliness, but from the overwhelming sense that I’d been given something sacred: an unspoken pact between two beings who shared the same mountain and the same winter and, somehow, the same need for peace. I stopped using the thermal camera after that. I didn’t need proof. I needed respect.

Years have passed. I’m older now, slower, with different dogs and the same cabin. The knocks still come—less often, but always three, always measured, always familiar. The footage is still in my desk drawer on an old drive. I’ve written instructions to be opened when I’m gone, because I don’t know what the right choice is anymore. I only know the choice I made then: to keep the trust.

People ask why I stay out here. I tell them I like the quiet, and that’s true. But it’s also where the three knocks live. It’s where the forest answers back. And sometimes at three in the morning, I wake smiling and whisper into the dark, “I hear you.” Then the mountain goes still again, and I can’t explain it in any language that fits—only that somewhere beyond my porch light, something is still watching, and it isn’t here to harm.