This Bigfoot Devoured a Hiker on Appalachian Trail In 1985 – BIGFOOT SIGHTINGS STORY

The Vanishing of Jack Morrison

A Ranger’s Account from the Smokies

Chapter 1: Into the Wild

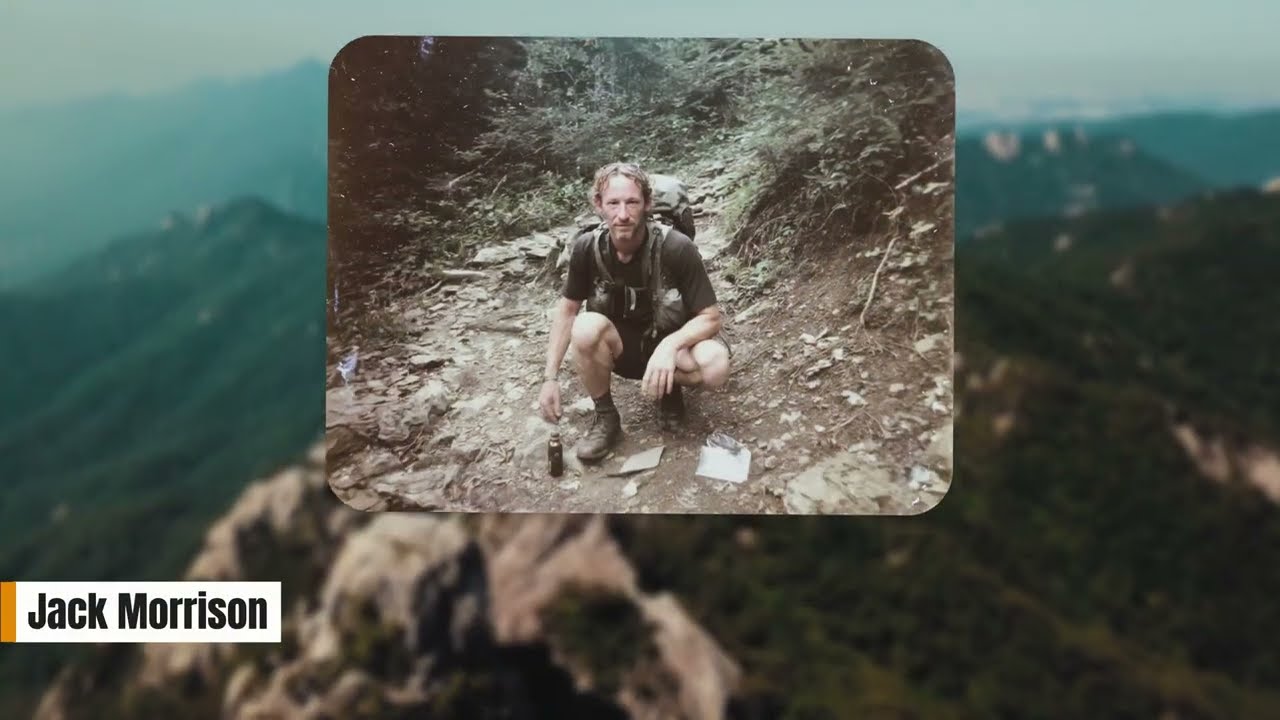

On October 18th, 1985, Jack Morrison, an experienced 32-year-old hiker, set out alone on a five-day section hike of the Appalachian Trail through Great Smoky Mountains National Park, straddling the Tennessee–North Carolina border. One week later, he vanished without a trace.

.

.

.

On October 28th, a search and rescue team found a destroyed campsite believed to be Jack’s, along with his torn backpack, scattered gear, and a camera containing photographs that would change everything. Jack’s body was never recovered, but the evidence left behind painted a terrifying picture of his final days—stalked, hunted, and ultimately consumed by something that should not exist.

Chapter 2: The Man Who Shouldn’t Disappear

Jack Morrison wasn’t a weekend warrior. He was a seasoned outdoorsman from Richmond, Virginia, with over fifteen years exploring America’s most challenging wilderness. A certified survival instructor, Jack had completed solo hikes on the Continental Divide Trail, sections of the Pacific Crest Trail, and multiple stretches of the Appalachian Trail. Friends described him as methodical, prepared, and able to survive in the backcountry longer than anyone they knew.

For October 1985, Jack planned a familiar route: a 47-mile section from Newfound Gap to Fontana Dam, passing through some of the most remote and pristine wilderness in the eastern United States. The Smokies’ AT section winds through dense old-growth forests, crosses numerous ridgelines above 5,000 feet, and includes stretches where hikers can go days without seeing another soul. For Jack, it should have been routine—a favorite challenge in his favorite place.

What Jack didn’t know was that he was walking into a wilderness harboring something far more dangerous than black bears or sudden storms.

Chapter 3: Whispers in the Woods

My name doesn’t matter. What matters is what I witnessed during my three years as a backcountry ranger in the Smokies from 1983 to 1986. I monitored remote sections of the AT, maintained shelters, and led search and rescue when hikers went missing.

We saw our share of accidents, injuries, and the occasional fatality. But nothing prepared me for what happened to Jack Morrison—or for the coverup that followed.

In 1984 and the first half of 1985, we started getting unusual reports from hikers in the park’s more isolated sections. These weren’t typical bear stories or complaints about rowdy campers. Experienced hikers reported massive bipedal tracks near their camps. Some described hearing vocalizations at night that didn’t match any known wildlife—deep, guttural howls, almost human but impossibly powerful. Many reported the unsettling sensation of being watched or followed, especially between Icewater Spring Shelter and Derek Knob Shelter.

Food caches were disturbed in ways that didn’t fit bear behavior—containers twisted and crushed with tremendous force. Most disturbing were the deer carcasses we found hung high in trees, sometimes twenty feet off the ground.

Park management attributed these incidents to a recovering black bear population or the rare presence of wild boar. Official policy was to downplay anything suggesting an unknown predator. “Bad for tourism, bad for the park’s reputation.” We were told to log such reports as bear activity and move on.

But those of us working the backcountry knew something else was out there.

Chapter 4: The Last Trek

Jack registered at the Sugarlands Visitor Center on October 17th. I was at the desk that day and spoke with him about trail conditions and weather. He was planning a standard five-day trek, carrying a full winter kit despite mild October temperatures. He showed me a worn AT guidebook filled with notes and maps from previous hikes—clearly, a man who knew what he was doing.

The weather forecast was perfect: mild days, cool nights, a chance of rain on days three and four. Jack planned to camp at designated sites: Icewater Spring Shelter, Mount Collins Shelter, Derek Knob Shelter, and near Molly’s Ridge before finishing at Fontana Dam.

He checked in by radio from Icewater Spring Shelter his first evening—normal conditions, good weather, no problems. His voice was relaxed and cheerful. That was the last time anyone heard from Jack Morrison alive.

Chapter 5: The Search

When Jack failed to arrive at Fontana Dam for his scheduled pickup on October 22nd, his brother Michael waited a day before notifying park authorities. Jack was known for his punctuality and had never missed a pickup in fifteen years.

Search and rescue began October 24th. I was part of the initial team retracing Jack’s planned route. At Icewater Spring Shelter, we found his signature in the logbook, dated October 18th: “Great weather, perfect hiking. Saw largest bear tracks I’ve ever encountered near the spring. Strange smell in the area—like rotting meat mixed with wet dog. Otherwise, excellent start.”

At Mount Collins Shelter, we found no evidence Jack had stayed there. The log had no entry from him, and there were no signs of his camp. Not alarming, but unusual.

The trail between Mount Collins and Derek Knob is a challenging, remote stretch—nearly nine miles of dense forest and steep climbs.

Chapter 6: The Destroyed Camp

On October 25th, about two miles before Derek Knob, 200 yards off the trail near a stream, we found what remained of Jack’s third campsite.

His tent, a high-quality four-season model, had been completely destroyed—not the methodical tearing of a bear, but shredded in long, parallel gashes suggesting claws far larger than any black bear. The aluminum tent poles were twisted into spirals, as if wrung by something with tremendous strength.

Jack’s backpack lay in pieces, scattered across fifty yards. His sleeping bag was torn into strips, hanging from tree branches twelve feet up. Food containers made of hard plastic were crushed flat, punctured with bite marks requiring jaw strength beyond any known animal in the region.

Most disturbing was the complete absence of Jack. No blood, no torn clothing, no sign of a struggle. It was as if he had vanished while something methodically demolished his camp.

Chapter 7: Tracks and Evidence

The forest around the campsite told a different story. Trees showed fresh gouges ten feet up the trunk, far higher than any bear could reach. The ground was disturbed in a pattern suggesting something very large had circled the camp multiple times before the attack.

Most unsettling were the tracks we found near the stream: seventeen inches long, seven wide, five distinct toes, claw marks extending beyond each toe. The stride was nearly four feet—upright, bipedal, at least eight feet tall.

We found Jack’s camera hanging from a tree branch three hundred yards away. The camera was undamaged, the strap deliberately placed over the branch—as if someone wanted it found.

Chapter 8: The Photographs

When we developed the film, the truth was undeniable. Jack had been photographing his stalker for at least two days before the attack.

The first unusual photo, taken October 19th, showed a large, dark figure partially obscured by trees a hundred yards ahead. At first glance, it looked like another hiker, but the proportions were distinctly nonhuman—nearly eight feet tall, covered in dark, shaggy hair, crouched behind an oak, watching Jack.

Subsequent photos showed the same figure at various distances—sometimes ahead, sometimes paralleling Jack’s route. One chilling sequence captured the creature drawing closer as Jack set up his camera for a sunset vista. In the third photo, the figure was only 150 yards away, clearly the same being.

The most disturbing image, taken October 20th, showed the creature standing in a clearing fifty yards away, staring directly at the camera. Its face was partially human but distorted: heavy brow, enlarged jaw, eyes reflecting light like an animal’s. Its expression was calculating, aware of being photographed, almost as if it allowed itself to be documented.

The creature’s arms hung past its knees, ending in disproportionately large hands. Its face, though humanoid, was distinctly primitive.

The penultimate photo showed the creature only thirty yards from Jack’s camp, partially concealed behind bushes, the campfire’s reflection visible in its eyes. The timestamp: 11:47 p.m.—Jack had been photographing it in near darkness, likely using a flash.

The final photo, taken the morning of October 21st, showed massive tracks in the mud beside Jack’s tent, and a handprint—twice the size of a human’s—pressed into the earth. The fingers were spread wide, pressed deep into the mud, as if steadying itself while examining the tent.

Chapter 9: The Journal

Hidden in a waterproof pouch among Jack’s gear, we found his trail journal. The entries confirmed the photographs’ timeline.

October 19th: “Something’s not right. Found huge tracks near my camp. Definitely not bear. Bipedal, humanlike, but way too big. At least 17 inches. Tracks circled my tent multiple times during the night. Whatever made them was studying my camp while I slept.”

October 21st, final entry: “It’s almost dark and I can hear them out there. Them—plural. There’s more than one now. They’re communicating, making sounds like nothing I’ve ever heard. Deep howls, almost like language. They’re coordinating. I think tonight they’re going to make their move. I’ve got my knife ready, but I know it won’t be enough. If someone finds this, know I documented everything. Photos are in the camera. This thing is real and it’s hunting in these mountains. People need to know.”

Chapter 10: The Feeding Ground

Our search team found more evidence within a quarter-mile radius: trees with fresh gouges up to twelve feet high, crude structures made from branches and logs arranged in a rough circle, each eight feet tall, built in a teepee-like configuration. Inside one, we found a cache of bones—mostly deer and small mammals, but the arrangement was unnatural.

Scattered human artifacts—fragments of clothing, camping gear, personal items—suggested previous victims. A driver’s license from 1982 belonged to a hiker missing three years before Jack. This was not the first attack.

We found a clearing, fifty feet in diameter, deliberately maintained. Personal artifacts and bones were arranged in patterns suggesting ritual or symbolic significance. This wasn’t just a feeding area. It was a shrine.

Chapter 11: The Coverup

When we returned with the camera and our findings, the response was immediate. The photographs were confiscated by the park superintendent. We were told Jack was the victim of a bear attack, that his body had been dragged away and was presumed lost. The unusual evidence—claw marks, twisted poles, massive tracks—was omitted from the official report.

We were warned that discussing the case outside official channels would result in termination and possible legal action. The photos, we were told, would be analyzed by wildlife experts, but would not be made public.

I knew what I had seen. This was no bear attack.

Chapter 12: Patterns in the Shadows

I began reviewing missing persons cases from the area. Between 1980 and 1985, seventeen hikers had vanished in the same stretch—experienced, solo hikers, no remains or only partial remains recovered, always in late fall or early winter.

The pattern was clear. A predator had learned to hunt humans, selecting isolated prey in the off-season.

Three weeks after Jack’s disappearance, I found the feeding ground. Personal artifacts, arranged bones, and evidence of environmental modification—diverted streams, constructed pools, geometric arrangements of posts and bones. This was not random. It was systematic, intelligent, and ongoing.

Chapter 13: The Williams Case

The disappearance of Marcus Williams in 1986 marked a turning point. Williams, a professional wilderness guide, vanished while documenting autumn wildlife. He carried motion-activated cameras and night vision equipment. When he failed to check in, a massive search was launched.

His camp was found, hastily packed, but most importantly, his cameras had captured the attack. The photographs showed five creatures surrounding his camp, coordinating, cutting off escape routes, actively searching for cameras. The last image showed Williams being overwhelmed.

Federal agents arrived within hours, confiscated all evidence, and required us to sign new confidentiality agreements. The official story: a fatal accident while photographing bears. No body was ever found.

Chapter 14: The Truth Suppressed

I learned from contacts in other parks that similar incidents had occurred throughout the Appalachians for decades. In every case, evidence was confiscated, incidents attributed to bear attacks or accidents, and families discouraged from asking questions.

I realized we rangers were being used as unwitting data collectors for a classified research program. Our reports and evidence disappeared into a federal black hole.

Within weeks, I was transferred to another section. The Williams case was closed as a probable fall from a cliff, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Chapter 15: Warning

I resigned from the Park Service in 1987, but I never forgot what I saw. Every year, one or two experienced hikers vanish from the same stretch of trail. The official explanations remain unchanged: bear attacks, falls, getting lost. But the pattern persists.

The creature responsible for Jack Morrison’s death—and the deaths of at least sixteen others I know of—is still active in the Smokies. It’s learned to be more careful, more selective, more thorough in eliminating evidence. But it hasn’t stopped hunting.

If you plan to hike the Appalachian Trail through Great Smoky Mountains National Park, especially between Newfound Gap and Fontana Dam, heed this warning: Never hike alone. Travel in groups. Avoid isolated campsites. If you encounter massive tracks, unexplained sounds, or the feeling of being watched, leave immediately.

The Park Service will tell you the greatest dangers are bears, weather, and getting lost. They’re lying. The greatest danger is something they refuse to acknowledge—something that’s been hunting humans in those mountains for decades.

Jack Morrison did everything right. None of it mattered. His camera survived. His photographs are locked away in government archives, too dangerous to release. But the creature that killed him is still out there, still hunting, still feeding on hikers who venture alone into the remote Smokies.

Don’t assume that because something isn’t supposed to exist, it can’t kill you. Jack Morrison made that mistake. His remains are still somewhere in those mountains, scattered across a feeding ground the Park Service keeps hidden. He deserved better. We all do.

End of Story