Tourists Encountered a BIGFOOT in the Pacific Northwest Mountains – Story

The Snowbound Truth

Chapter 1: Shadows in the Snow

I haven’t slept properly in six months. Every time I close my eyes, I’m back there in the snow, running through those silent trees, hearing the sounds behind me—crunching, breathing, the echoes of terror. People always ask what happened: friends, family, even the therapist my parents made me see. I tell them it was a bear attack. That’s what the official report says. That’s what everyone believes. But I was there. I saw what happened to my friends. And I know bears don’t hunt like that. Bears hibernate in winter.

.

.

.

It was supposed to be a simple trip—three days in the Cascade Mountains in Washington State, late January. Just three friends in our mid-twenties who wanted an adventure, wanted to prove we could handle real winter camping. We’d done summer trips, sure, but winter was different. We thought we were ready. We thought we could handle it. We weren’t ready. We couldn’t handle it. And two of my best friends paid the price for that mistake.

We left on a Friday morning in a borrowed SUV, snow chains already fitted. The drive to the trailhead took about three hours. We arrived around noon, the sun high and bright against the snow. I remember how excited we were, loading our packs, checking our gear, snapping photos by the trail marker. We looked like real mountaineers in our new jackets, heavy boots, ice axes strapped to our packs. The snow was deep—two feet on the trail, maybe deeper in spots. Other hikers had passed through recently, so the path was partially broken, which made the going easier. Still, we had to work for it, lifting our legs high with each step, packs heavy on our backs. The temperature was cold but not brutal, maybe twenty degrees. The sun helped.

We hiked for about three miles before finding a good spot to set up camp—a clearing near a frozen creek, trees around the edges for shelter from the wind. The snow was pristine there, unmarked except for some animal tracks we couldn’t identify. Maybe rabbit, maybe fox. We didn’t think much of it. Setting up camp took longer than we expected. The ground was frozen solid under the snow, so driving in tent stakes was hard work. We had two tents—one for two of us, one for the third. We spent a good hour clearing snow, setting up, building a fire ring by digging down to bare ground and lining it with rocks we found. Next came the food bags. We knew we were supposed to hang them in trees to keep animals away, but honestly, we didn’t really know what we were doing. We found a branch that looked high enough, threw a rope over it, tied the bags up. Looking back, they were way too low—maybe eight feet off the ground. But we didn’t know any better.

By the time we finished, the sun was sinking toward the mountains and the temperature dropped fast. That’s one thing about winter camping that surprised us. In summer, you have those long, warm evenings. In January, darkness comes early and the cold comes with it. We got the fire going, cooked freeze-dried meals in our mess kits—beef stroganoff and chicken teriyaki, I think. Tasted like cardboard, but we were hungry enough not to care. We made hot chocolate from packets and sat around the fire, joking about being real mountain men. My friend said his girlfriend wouldn’t believe he actually did this. Another complained about his sleeping bag not being as warm as advertised.

That first night was cold but peaceful. We heard wind in the trees, occasional clumps of snow falling from branches, the crack of wood in the fire. Normal sounds. Natural sounds. We stayed up for a while, talking about stupid stuff, feeding the fire. Eventually, the cold drove us into our tents. I remember lying in my sleeping bag, listening to the wind, feeling proud that we’d made it this far. The sleeping bag was warm enough. My pad insulated me from the frozen ground, and I was tired from the hike. I fell asleep easily, thinking about the next two days, the photos we’d show people when we got back. I slept fine that night. It was the last time I would.

Chapter 2: Signs and Warnings

I woke up to shouting. The sun was barely up, the light inside my tent that dim gray of early morning. One of my friends was outside yelling about the food. I climbed out of my sleeping bag, the cold hitting me immediately, and unzipped my tent. The temperature had dropped overnight, probably down to ten degrees or lower. My breath came out in thick clouds.

One of the food bags was on the ground, ripped open, contents scattered in the snow. Freeze-dried packets torn apart, wrappers everywhere, trail mix spilled and trampled. The other bag was still hanging, but something had tried to get at it too. The snow around the bags was disturbed, trampled down. There were marks everywhere, like something had been moving around out there for a while. We stood there in our long underwear and jackets, staring at the mess, trying to figure out what happened. My friend said it must have been a wolverine. Another suggested a fox. We didn’t want to admit we’d hung the bags too low, that this was our fault. And we definitely didn’t want to admit that something bigger might have come into our camp while we slept.

One friend joked, “Good thing bears are hibernating, right?” We all laughed, but it was nervous laughter. Something had been here. Something strong enough to pull down a bag and tear it apart. We cleaned up what we could, salvaging the food that was still sealed. Lost maybe a third of our supplies. Not great, but we’d planned for three days, and this was only day two. We’d be fine.

After breakfast—more freeze-dried food, oatmeal this time—we decided to explore the area. The frozen creek looked interesting, winding up into the forest. We followed it upstream. The snow was deeper off the trail, sometimes up to our thighs. We took turns breaking trail, switching off when the person in front got too tired.

Maybe half a mile from camp, we found the footprints. They were in a patch of fresh snow near the creek, clear as day. At first, I thought they were from another hiker, but as we got closer, I realized they were way too big. Each print was easily twice the size of our boots. The stride between them was massive, longer than any human could step. We stood there, staring at them—five toes on each print, like a human foot, but enormous. The prints were deep, pressed far down into the snow, like whatever made them was incredibly heavy.

My friend laughed and said, “It must be Bigfoot.” We all laughed. It was absurd. Bigfoot wasn’t real. These had to be our own footprints from yesterday, somehow melted and refrozen. Snow does that sometimes, right? But I remember thinking even then that the explanation didn’t quite fit. These prints were in fresh snow that had fallen overnight, and they didn’t look melted. They looked pressed down with clear definition on each toe. We took some photos with our phones. Looking at them now, you can see how big they are compared to our boots in the frame. But at the time, we told ourselves they were just weird snow formations. Because the alternative was too crazy to consider.

We spent the afternoon back at camp, building a better windbreak around the tents with fallen branches, gathering more firewood. The work kept us warm, but by late afternoon, the snow started falling again—big, heavy flakes that stuck to everything. As dusk approached, we heard something that made us stop working. A sound echoing through the forest. A deep, hollow knocking, like someone hitting a tree with a baseball bat. Knock, knock, knock. Three times, then silence. Then from a different direction, the same thing. Knock, knock, knock.

We looked at each other. My friend said maybe it was a woodpecker, but we all knew woodpeckers don’t sound like that, and they don’t come out at dusk in winter. Another friend suggested it might be trees cracking from the cold. That made more sense, so we accepted it. But the knocking kept happening, coming from different spots around us, almost like something was communicating, moving around the perimeter of our camp. We didn’t say it out loud, but I know we were all thinking the same thing. Something was out there, and it knew we were here.

Chapter 3: The Night Visitor

We got the fire going early, made dinner quickly—more freeze-dried meals, already getting tired of them. The snow fell heavier. We sat around the fire trying to act normal, trying to keep the conversation going, but the jokes had stopped. We kept looking into the darkness beyond the firelight, seeing shapes in the shadows that probably weren’t there.

Then we heard branches breaking—loud cracks and snaps in the forest, the sound of something large pushing through the undergrowth, the crunching of snow under heavy weight. It was moving around us, staying just beyond where the firelight reached. We’d see the trees shake, hear the branches snap, but never saw what was causing it. My friend threw more wood on the fire, making it bigger, brighter. We sat closer to the flames. Nobody wanted to say it, but we were all scared. This wasn’t a fox or a wolverine. This was something big, something that wanted us to know it was there.

We decided to turn in early, keep the fire going, pile extra wood within reach. As we headed to our tents, the sound stopped. The forest went quiet, almost too quiet. No wind, no small animals, nothing. Just silence and falling snow.

Inside my tent, I lay in my sleeping bag, fully dressed, listening. My heart was pounding. I told myself it was just my imagination, just nerves from being in an unfamiliar environment. Animals are more scared of us than we are of them, right? That’s what people always say. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was watching us. Something that had been watching us all day.

I don’t know what time it was when I woke up. Middle of the night, pitch black inside my tent. I woke because I heard breathing. Not my own breathing. Something outside my tent. Heavy, raspy breaths. Deep and slow, the sound of something big pulling air in and pushing it out. I could see my own breath in the cold air, little clouds in the darkness, and I lay absolutely still, too terrified to move.

Then I heard the footsteps, slow, deliberate, crunching through the crusty snow that had frozen on top of the fresh powder. Something was walking around our campsite. Each step made a distinct crunch, and I could tell whatever it was, it was massive. The footsteps circled my tent. I heard them move past one side, crunching around the back, coming up the other side. Then they stopped right outside my tent wall, maybe three feet from my head. I held my breath. I couldn’t move. My hands were clenched inside my sleeping bag, my whole body rigid with fear.

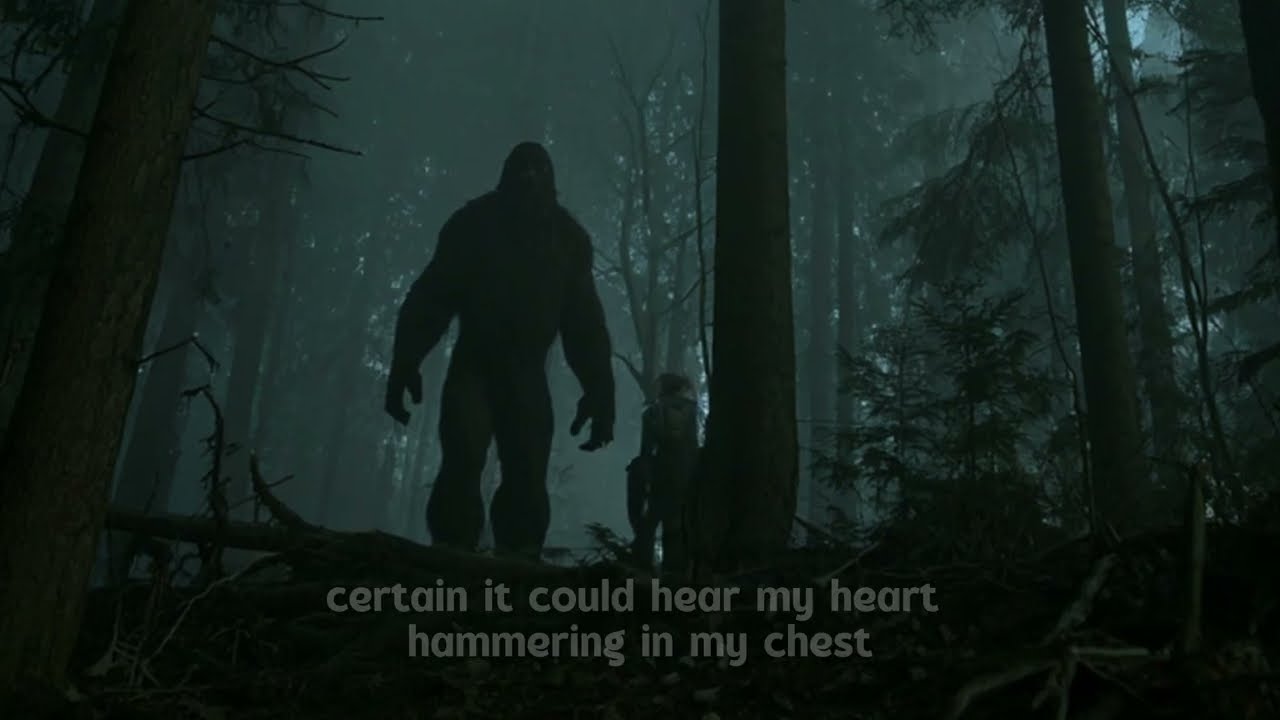

The breathing continued, deep, raspy, almost wheezing. I could smell something too, even through the tent fabric—a rank, musty odor, like wet dog mixed with something that had been dead for days. The tent wall flexed inward slightly, like something was leaning against it or sniffing it. For what felt like forever, but was probably only a minute, whatever it was just stood there, breathing, waiting. I was certain it knew I was inside, certain it could hear my heart hammering in my chest.

Then it moved away. I heard the footsteps crunch through the snow toward the other tent. I heard my friends whispering frantically. They were awake, too, hearing the same thing I was hearing. I didn’t sleep the rest of that night. I lay there in the darkness, listening to every sound, waiting for the tent to rip open. But eventually, the sounds faded. The breathing stopped. Whatever it was moved off into the forest.

Chapter 4: Daylight Terror

When dawn finally came, I’ve never been so grateful to see daylight. We all emerged from our tents looking like we’d seen a ghost. None of us had to ask if the others had heard it. We all had. We stood in the cold morning air, our breath steaming, and looked at our campsite. Both food bags were on the ground, completely torn apart. Not a scrap of food left. Our supplies were gone. But that wasn’t the worst part.

One of the tents, the one my friends had been sleeping in, had marks scraped down the side. Long scratches in the frozen nylon, like something with claws or fingers had dragged down the tent wall. The marks were up high, maybe seven feet off the ground. And the footprints—they were everywhere. The same massive prints we’d seen at the creek, all over our campsite, around the fire ring, around both tents. A clear trail leading into the forest where whatever made them had disappeared.

We stood there in silence, looking at the evidence. This wasn’t a fox. This wasn’t a wolverine. This was something big, something intelligent enough to deliberately terrorize us. My friend said we should leave right now, pack up and head back to the trailhead. But another pointed out we’d only planned to stay one more night anyway. We were supposed to pack up tomorrow morning. If we could just get through one more night, we’d be fine. We’d come here to camp for three days and we’d already made it two. Leaving now felt like admitting defeat.

I wish we’d left. I wish we’d listened to that first instinct and gotten out while we could. But we were young and stupid and didn’t want to admit we couldn’t handle it. So, we stayed.

Chapter 5: The Hunter Revealed

We spent the morning close to camp, keeping the fire going, staying alert. The snow had stopped, but the sky was overcast, threatening more. We rationed what little food we had left—some energy bars, a couple of meal packets that had survived. We melted snow for water. We didn’t talk much. We were all scared, even if we didn’t want to admit it out loud.

Around noon, someone suggested we take a short hike just to stretch our legs, maybe kill some time before we packed up the next morning. In retrospect, it was the worst decision we could have made. But sitting in camp was making us more nervous, and moving felt better than waiting. We didn’t go far, maybe half a mile from camp, following a ridge through the snow. The terrain was harder here, deeper drifts, more obstacles.

We were just about to turn back when we found it. The structure was built in a small clearing between evergreens—a crude lean-to made from broken branches, deliberately arranged and leaned together to form a shelter. The branches were thick, some of them six or seven feet long, snapped off from trees and stripped of their smaller growth. This wasn’t something that had fallen naturally. This was built.

We stood at the edge of the clearing staring at it. My friend suggested maybe another camper had built it, or some hunter, but there were no footprints around it except the same massive prints we’d been seeing. And the structure looked old, weathered, covered in snow that had been there for weeks.

Near the structure, we found bones—half buried in the snow. Deer bones, maybe rabbit, and something larger we couldn’t identify. The bones were cracked open, the marrow gone. They looked gnawed. The smell hit us then. Even in the cold, there was an awful stench—rotten meat mixed with that wet dog smell we’d smelled the night before. It was so strong it made my eyes water. The smell of something that had been living here, eating here for a long time.

My friend found hair caught on a low branch near the structure. He called us over and we all looked at it. Dark, coarse hair, thick strands, frozen stiff, too long and thick to be from a bear, too coarse to be from a deer. Maybe four or five inches long, matted and filthy. That’s when we all finally admitted out loud what we’d been thinking since the night before. Something was living out here. Something big and intelligent and territorial. And it had found our camp. We needed to leave now.

Immediately, we practically ran back to our campsite, slipping and sliding through the snow in our panic. When we got there, we found it destroyed. Both tents ripped open, partially collapsed. Poles bent and snapped. Our gear scattered everywhere. Sleeping bags dragged out into the snow. Backpacks torn open and emptied, contents strewn across the campsite. Cooking equipment smashed and scattered. Pots bent like they’d been stomped on. One of the sleeping bags had been dragged into the woods. Another was ripped to shreds, insulation scattered like artificial snow over everything. Whatever had done this wanted us gone—or worse. This wasn’t just an animal looking for food. This was deliberate destruction, a message.

Chapter 6: The Escape

We didn’t need to discuss it. We started grabbing what we could salvage, stuffing things into our damaged packs. We were panicking, moving fast, checking over our shoulders constantly. The sun was already low. We’d spent more time exploring than we realized. It was past two in the afternoon, and in January in the mountains, we had maybe three hours of daylight left. Four at most. We should have been more careful about what we grabbed. We should have thought about what we needed. But we were terrified and in a hurry and we just grabbed whatever was closest and started packing.

Then we heard it—a sound that made our blood freeze. A roar, deep and guttural, echoing across the snowy landscape. It came from the treeline at the edge of our clearing, maybe a hundred feet away. It was like nothing I’d ever heard before. Not like a bear, not like a mountain lion, not like any animal I knew. It was loud enough to hurt my ears, loud enough that I felt it in my chest.

We all turned toward the sound, and that’s when we saw it. It stepped out from between the trees and for a second my brain couldn’t process what I was seeing. It was too big, too wrong. Nothing that large should be able to move that quietly through the forest. Eight or nine feet tall, maybe more, covered in dark fur, almost black against the white snow. The shape was humanoid—two arms, two legs, walking upright. But the proportions were all wrong. The arms were too long, hanging down past where its knees would be. The shoulders were massive, wider than any human’s, with a thick, muscular chest. The head sat low between those shoulders with almost no visible neck. The face, I only got a glimpse, but I’ll never forget it—not quite human, not quite ape. The features were flat with a broad nose and a heavy brow. And the eyes—pale eyes that stared directly at us, cold and intelligent and calculating.

It stood there at the edge of the clearing, snow falling around it, steam rising from its breath, completely still, just watching us. Nobody moved. The three of us stood frozen next to our destroyed tents, packs half loaded, staring at this creature that shouldn’t exist. The only sound was our own panicked breathing and the wind in the trees. Even the wind seemed to quiet, like the whole forest was holding its breath.

Then it took a step forward, then another, moving through the deep snow like it weighed nothing, like the drifts that exhausted us were barely an inconvenience. Each step was deliberate, purposeful. It wasn’t charging. It was approaching slowly, studying us.

One of my friends yelled—a wordless shout of pure fear that broke the spell. That’s all it took. All three of us grabbed our packs and ran. We ran down the trail we’d hiked up two days before, running through snow that came up to our knees in places. Every step was a battle, our legs burning with the effort of lifting our feet out of each drift and plunging forward again. Our packs bounced on our backs, straps cutting into our shoulders. But we didn’t stop. We couldn’t stop.

Behind us, we heard it crashing through the forest, trees snapping, heavy footfalls punching through the crust of the snow. It was following us, and it was fast, faster than we were. It moved through that deep snow like it was running on pavement while we floundered and struggled.

I fell first. My foot caught on something buried under the snow, a root or a log, and I went down hard, face first into a drift. For a second, I was buried, snow in my mouth and nose, panicking. My friends grabbed my pack and hauled me up, and we kept running. The creature roared again, closer now. So close I could hear its breathing, heavy and ragged, like an engine laboring. I could hear the snow crunching under its weight, hear the branches breaking as it pushed through the forest behind us.

We reached a fork in the trail. One path went left, downhill toward the main trail and eventually the trailhead. The other went right, up toward a ridge. We should have stayed together. You never split up when something is chasing you, but in the moment, in our panic, it seemed like the smart thing to do. One friend yelled to split up, maybe confuse it, meet back at the trailhead. Before we could argue, he took off down the right path toward the ridge. Me and my other friend went left, downhill, running as hard as we could.

We heard the screaming almost immediately. It came from the right path, high-pitched and terrified, and cut off suddenly, just stopped like someone had flipped a switch. We both stopped running, stood there in the snow, breathing hard, looking at each other. We knew what that meant. We both knew. But our brains couldn’t accept it. My friend was fine. He’d just fallen. He’d catch up with us. But we knew deep down—we knew.

My friend grabbed my arm and pulled me forward. We had to keep moving. We ran down the trail, the screaming still echoing in my head, trying not to think about what had just happened. We ran until our lungs burned from the cold air, until our legs felt like they would give out. The trail was getting harder to see as the light faded and fresh snow fell. Everything looked the same—white and gray and shadowed. The trees pressed in on both sides, dark and oppressive.

I heard something off to our left—movement in the trees, branches shaking, snow falling from the boughs. Was it circling us, or was there more than one? I couldn’t tell. Everything was happening too fast. My friend tripped over a buried log and went down hard. I heard the snap as his ankle twisted, heard his gasp of pain. He tried to get up, but collapsed back into the snow. His ankle was swelling, his face pale with pain.

I tried to help him up, get his arm over my shoulder, but he could barely put weight on it. We managed maybe ten feet before he collapsed again. We weren’t going to make it. Not together. Not with his ankle like that. That’s when we saw it ahead of us, cutting off the trail. It stepped out from behind a massive evergreen, and we realized we had been herded. It had circled around while we ran, and now it was between us and safety.

Up close, it was even more terrifying. The face was a twisted mix of human and ape, with skin visible through patchy fur around the mouth and eyes. When it opened its mouth, I could see teeth—large, yellowed, sharp. Its breath came out in clouds of steam in the cold air. The smell was overwhelming even from twenty feet away—rot and musk and something chemical that made my stomach turn. It moved toward us slowly. Each step pressed deep into the snow. It was in no hurry. It knew we had nowhere to go.

My friend pushed me hard, shoved me backward, and yelled at me to run. He picked up a thick branch from the snow, heavy and as long as his arm, and turned to face the creature. The last thing I saw as I turned and ran was my friend standing there in the snow, branch raised like a weapon, facing something that stood twice his height. The creature took another step toward him. Then I was running, crashing through the forest off trail, and I couldn’t see them anymore. I heard sounds behind me—a roar, a scream that might have been human or might have been something else. Crashes and thuds. Then silence. Just the wind and my own ragged breathing and the crunch of my boots in the snow.

Chapter 7: The Aftermath

I ran until I couldn’t run anymore. I left the trail completely, just plunged into the forest, trying to put distance between me and whatever was happening back there. Branches tore at my face and jacket. I fell multiple times, got up, kept going. No direction, no plan, just movement. Eventually, my legs gave out completely. I collapsed behind a fallen log, half buried in snow, and tried to quiet my breathing. My lungs burned from the cold air. My legs were shaking. I was covered in snow and sweat and probably bleeding from all the branches that had scraped my face.

It was dark now, completely dark with heavy clouds blocking any moonlight. I couldn’t see more than a few feet in any direction. The snow was still falling, muffling all sound. I heard it searching for me. Branches breaking, that distinctive heavy crunch of something massive moving through snow. It was out there, moving through the forest looking for me. I heard trees being shaken, snow falling from branches in heavy clumps. I heard what might have been sniffing sounds, like it was trying to track my scent. It passed close by, close enough that I could smell it, that rank odor of rot and musk. I pressed myself into the snow behind the log and didn’t breathe.

It moved away, kept searching in another direction, but I stayed where I was. I was too terrified to move and too cold to think clearly. I knew I was getting hypothermic. I was shivering uncontrollably, my fingers and toes going numb. But moving meant being found, and being found meant dying.

I stayed there for hours, maybe three, maybe five. Time stopped meaning anything. It was just cold and darkness and fear. Occasionally, I’d hear something moving in the forest, hear that heavy crunch of snow, and I’d freeze and wait for it to pass. Eventually, I stopped shivering. That’s a bad sign. I knew that, even through my foggy thoughts. When you stop shivering, it means your body is shutting down. I was dying of hypothermia. I had to move or I’d freeze to death behind this log.

When the first gray light of dawn started filtering through the trees, I forced myself to stand. My legs barely worked. My fingers were white and wouldn’t close properly. But I was alive and I had to stay alive. I had no idea where I was. The forest looked completely different in the snow. Everything was white and gray and unfamiliar.

I picked a direction that seemed like it might be downhill and started walking. I walked for hours—or maybe it was minutes. Time was weird. My brain was foggy from hypothermia and exhaustion and shock. I fell down a lot. Got up, kept walking. I was eating snow for water, which I knew made hypothermia worse, but I was so thirsty I didn’t care. The sun came up properly, though I couldn’t see it through the clouds. Everything was just varying shades of gray. I kept walking, one foot in front of the other. If I stopped, I’d die. That was the only thought I could hold on to.

I don’t remember finding the snowmobile trail. One minute I was in the forest, the next I was standing on a groomed trail, packed snow under my feet instead of deep powder. I stood there swaying, trying to understand what I was seeing. I heard an engine—a snowmobile coming down the trail. I tried to wave, but my arms barely moved. I think I fell down. I remember lying in the snow, seeing the snowmobile stop, seeing someone get off. They were talking to me, but I couldn’t understand the words. Then I was on the back of the snowmobile, holding on to the driver, and we were moving fast. Trees rushed past, wind on my face. I think I passed out.

I woke up in a hospital bed. Bright lights, warm. There were tubes in my arm and blankets piled on top of me. My fingers and toes hurt—the kind of burning pain that means frostbite, but not too severe. I was lucky. A few more hours in the cold and I would have lost fingers or toes or my life.

Chapter 8: The Official Story

The rangers came first, then police. They asked so many questions. Where were my friends? What happened? Why was I alone? How did I get lost? I told them everything. The campsite, the destruction, the footprints, the creature, the chase. My friends—I told them every detail I could remember. Everything I’d seen. They didn’t believe me. I could see it in their faces. They were professional about it, taking notes, nodding along. But they thought I was confused, hallucinating from hypothermia, making excuses.

One officer asked if I’d hit my head during the fall I must have taken. A ranger asked if we’d been drinking or if there were any drugs involved. I kept trying to explain. The footprints were real. The destroyed campsite was real. My friends didn’t just wander off. Something took them, something huge and strong and not human. But they just nodded and wrote in their notepads and didn’t believe me.

Search and rescue went out immediately. Multiple teams on snowmobiles and skis spreading out across the area where I’d been found. They had my description of where we’d camped, what trails we’d taken. They had GPS coordinates from the trailhead. They found the campsite that same day. It was exactly where I said it would be, and it was destroyed exactly how I described. Tents ripped apart, gear scattered, everything torn up. They took photos, documented everything. It matched my story perfectly.

On the alternate trail, the one my friend had taken when we split up, they found evidence of a struggle. Blood in the snow, already frozen, drag marks leading into the woods. They followed the trail and found him a quarter mile into the forest, or what was left of him. The official report said he’d been mauled severely. His body was partially buried in snow and scattered by animals. They found enough to identify him, but not enough to bring back. The ranger who told me this had trouble looking at me. He said it was one of the worst things he’d seen in twenty years of search and rescue.

They never found my other friend. They found his backpack near a rocky outcrop, torn to pieces. They found clothing, also torn. They found more blood, but no body, just those pieces and drag marks that ended at a cliff edge. The search continued for two weeks. They brought in dogs, helicopters when the weather cleared, thermal imaging equipment. They covered a radius of ten miles from our campsite. They found nothing else.

Eventually, they found a bear den three miles from where we’d camped. Old, used recently, with some of our gear dragged into it—one of our food bags, a torn sleeping bag, some scattered equipment. The theory came together quickly after that. A bear—had to be a bear. Probably a black bear that hadn’t hibernated properly, maybe woken up during a warm spell, was desperately hungry. We’d set up camp in its territory, maybe near its den. The smell of food attracted it. It came into our camp, destroyed everything, attacked when we ran.

Three weeks after they found the den, they shot a large black bear in the area, estimated at over four hundred pounds. They tested it and found human DNA. That sealed it. This was the bear that killed my friends. Case closed. Tragic bear attack. Three young men who didn’t know what they were doing went winter camping in bear country and paid the price.

Chapter 9: What Remains

They let me out of the hospital after four days. I had moderate frostbite on three fingers and two toes, but they’d caught it in time. I had bruises and cuts from running through the forest. I was dehydrated and malnourished. But I was alive. My friends were dead. And I was alive.

I tried to tell people what really happened—my parents, my other friends, the people at the memorial service. I tried to explain that it wasn’t a bear, that I saw what attacked us, that the footprints were real and impossible. Nobody believed me. They were sympathetic. You’ve been through trauma. Hypothermia causes hallucinations. The mind plays tricks in extreme stress. They recommended therapy. Medication. They recommended I stop talking about it and focus on healing.

My therapist was gentle but firm. She explained that when people experience traumatic events, especially involving hypothermia and oxygen deprivation, the brain can create false memories to explain what happened. She said my mind probably took the real elements—the bear, the attack, my friends’ deaths—and transformed them into something else, something easier to process or something that felt more controllable. She asked me why I thought I saw a creature instead of just admitting it was a bear. I couldn’t answer that. Or maybe I didn’t want to.

After a month of everyone telling me I was wrong, I stopped arguing. I stopped trying to convince people. When asked what happened, I said, “Bear attack.” When pressed for details, I said, “I don’t remember much. I was in shock.” People seemed satisfied with that. They stopped looking at me with concern and pity. Life moved on.

But I remember. I remember the footprints—too big, too human-shaped, too clear to be anything normal. I remember the way it moved through the snow like it weighed nothing. I remember its face when it stepped out of the trees. I remember the intelligence in those pale eyes.

Bears don’t build structures. Bears don’t deliberately destroy campsites to terrorize people. Bears don’t herd their prey by circling around to cut off escape routes. Bears don’t make that sound, that roar that I still hear in my nightmares. And bears hibernate in winter. Everybody knows that.

Chapter 10: The Secret Truth

I moved away from the Pacific Northwest. Couldn’t stand to be near those mountains anymore. I can’t look at snow without my chest tightening, without feeling that cold terror creeping back. Winter is the worst. Every year when the temperature drops and the first snow falls, I’m back there in those mountains, running through the trees, hearing my friends scream. I don’t camp anymore. Don’t even like being in forests. My friends invite me hiking and I make excuses. They think I’m being paranoid, that I need to face my fears and get back out there. They don’t understand that some fears are justified. Some fears keep you alive.

Sometimes late at night when I can’t sleep, I search online forums about cryptids, websites dedicated to Bigfoot sightings, message boards where people share their experiences. There are hundreds of stories, thousands maybe—people who’ve seen something in the woods, something that shouldn’t exist. Most never report it officially. Most get told they’re crazy when they try to share what happened. I read about the Pacific Northwest sightings, especially Washington, Oregon, Northern California. So many stories from those mountains—people hearing wood knocking in the forest, finding massive footprints, seeing something huge and dark moving between the trees, campsites destroyed for no apparent reason.

Some stories are obviously fake. Some are clearly misidentifications—seeing a bear and imagining something else. But some ring true. The details are too specific, too similar to what I experienced—the way the creature moves, the intelligence behind its actions, the deliberate nature of its behavior.

I’ve never posted my own story, never added to those forums or reached out to the people who run those websites. What would be the point? I’d just be one more anonymous voice claiming to have seen something unbelievable. And I don’t want the attention. Don’t want the debates about whether I’m telling the truth or the armchair experts picking apart my story. But I read them. I read every story from the Cascades, every report from Washington State, every account of winter encounters. And I know I’m not alone. Other people have seen it. Other people have survived encounters. Some probably didn’t survive, and their disappearances got written off as getting lost or falling or some other mundane explanation.

The official statistics are staggering when you actually look at them. Hundreds of people vanish in national parks and forests every year. Most are found eventually, but some never are. Some just disappear without a trace, and the cases go cold. Search and rescue does what they can, but these wildernesses are vast—millions of acres where a person could vanish forever. How many of those disappearances are really just people getting lost? How many are accidents, and how many are something else?

I think about the ranger who told me about finding my friend. The look on his face when he described it. He said it was one of the worst things he’d seen in twenty years. Bears attack people sometimes. That’s true. But do they usually result in something that traumatizes an experienced search and rescue ranger? I wanted to ask him what it really looked like, what he really thought happened, but I didn’t. I was too afraid of the answer.

The bear they killed, the one they said had human DNA on it—I’ve always wondered about that. Did it really kill my friends? Or did it just scavenge the bodies afterward? Bears are opportunistic. They’ll eat carrion if they find it. Maybe they found the remains and that’s how the DNA got transferred. But nobody wanted to consider that possibility. A bear attack was neat and simple and explainable. Case closed.

I looked up the den they found. I requested the search and rescue reports through a public records request. Spent hours reading through the documentation. The den was three miles from our campsite—three miles through difficult terrain and deep snow. Would a bear really drag gear that far? The sleeping bag, the food bag, pieces of equipment—all dragged three miles to a den? And the bear they shot—I saw the photos in the report. It was big, sure. Four hundred pounds is large for a black bear. But was it big enough to make footprints twice the size of a human’s? Was it big enough to reach seven feet up a tent wall to leave those scratch marks? Was it intelligent enough to systematically destroy our campsite while we slept? To circle around and cut off our escape, to hunt us with what seemed like deliberate strategy?

Black bears can stand on their hind legs. They can look tall when they do, but they don’t walk upright for extended periods. They don’t move through deep snow with the ease that thing demonstrated. They don’t have the body proportions I saw—the long arms, the massive shoulders, the humanoid gait.

But I don’t say these things out loud anymore. I learned that lesson. People don’t want to hear it. They want the simple explanation. They want to believe that the wilderness is dangerous but understandable, that the threats are known and documented. They don’t want to consider that there might be something else out there, something we don’t fully understand.

I don’t know what I’m supposed to do with this knowledge. I can’t prove it to anyone. I can’t make anyone believe me. I can’t go back and change what happened. All I can do is live with it, carry it, try to build some kind of life around this massive trauma. The therapist says I should focus on healing, on moving forward, on accepting that what happened was a tragedy, but it’s in the past. She wants me to stop dwelling on the details, stop questioning the official explanation, stop searching online for validation.

She thinks my obsession with what really happened is preventing me from processing the grief and moving on. Maybe she’s right. Maybe I am obsessing. Maybe my inability to let go of my version of events is just a way of avoiding dealing with the real issue—that my friends are dead and nothing I think or believe or prove will bring them back.

But I can’t let it go. Because if I admit it was just a bear, if I accept the official story, then I’m saying I don’t trust my own eyes, my own memory, my own experience. I’m saying that everyone else knows better than I do about what happened to me. And once you start doubting your own perception of reality, what do you have left?

So I live in this strange limbo. Publicly, I agree with the bear explanation. Privately, I know the truth. I go through the motions of normal life while carrying the secret knowledge that most people would dismiss as delusion. I smile and nod when people mention bears. Stay quiet when documentaries claim Bigfoot is just a myth. Keep my experiences to myself.

Sometimes I wonder if I should write it all down. Not for publication, not to convince anyone, just to have a record—so that if something happens to me, if I disappear or die in some unexpected way, there’s a document somewhere that tells the real story. Maybe I’ll hide it where someone will eventually find it. Maybe I’ll leave instructions to open it after I’m gone. Maybe nobody will ever read it, but at least it would exist. Or maybe I’ll keep it locked inside, take it to my grave, let it die with me. Let the official story be the only story. Let my friends be remembered as victims of a bear attack. Tragic casualties of wilderness camping gone wrong. Let the creature remain undiscovered, unexplained, existing only in folklore and disputed sightings and dismissed testimonies.

I don’t know which option is right. I don’t know if there is a right option. What I do know is this: If you’re reading this, if you’re considering winter camping in the Pacific Northwest, if you’re thinking about heading into those mountains for an adventure, be careful. Be more prepared than you think you need to be. Don’t underestimate how dangerous it is out there. Don’t assume you understand all the risks. And if you see footprints that are too big, if you hear sounds that don’t match any animal you know, if you feel like something is watching you from the darkness beyond your campfire, trust that instinct. Pack up and leave. Don’t wait to see if you’re right. Don’t try to get proof. Don’t stay just one more night.

Because sometimes the truth is far colder than the snow.