Two Veterans Captured a BIGFOOT in 1987. They Have Kept It Hidden for 38 Years

Chapter 1 — The Last Man Who Knows

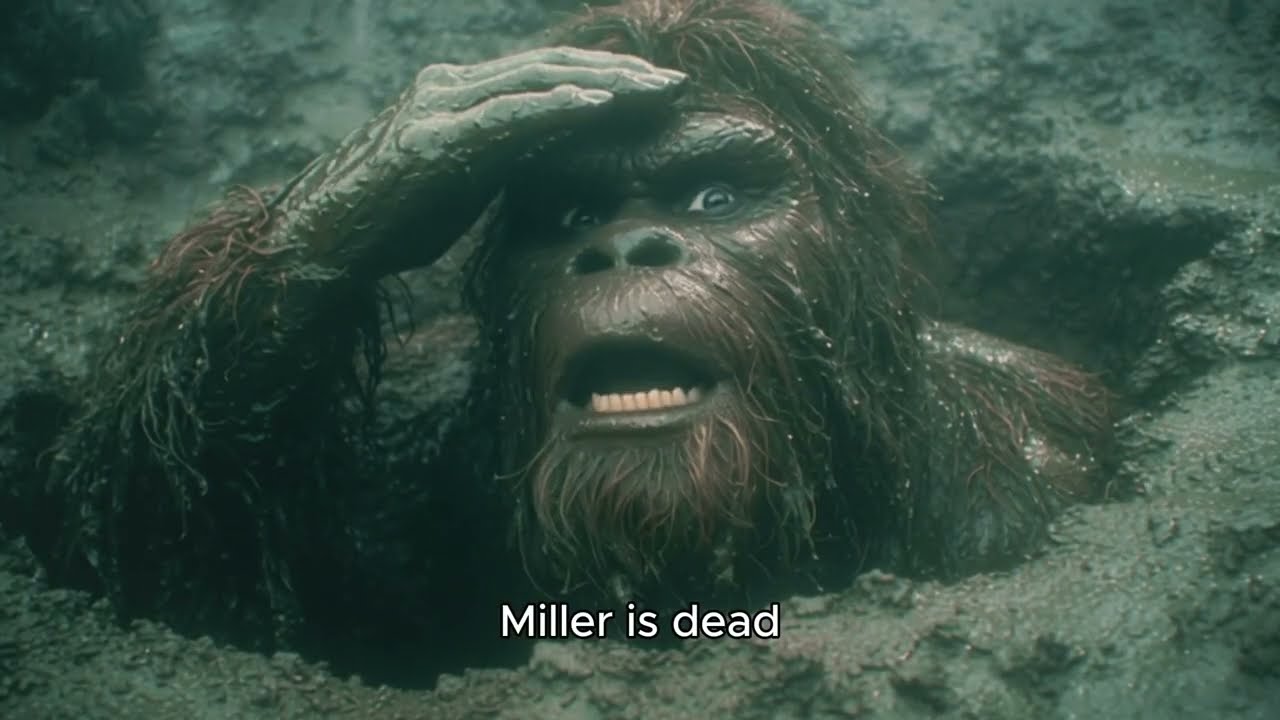

They say three people can keep a secret only if two of them are dead. As of Tuesday morning, Miller is dead—a heart attack in his sleep, face turned toward the rain-smeared window, rifle across his lap like he was still standing watch. Downstairs, behind ten feet of dirt and a steel door, the prisoner we’ve kept in concrete dark for thirty-eight years is alive, breathing, waiting. He isn’t talking to anyone. That leaves me.

.

.

.

My name is Jack. In another life I was a corporal in First Recon, the kind of man trained to catalog threats and strip emotion out of decisions. Miller—Sergeant Miller, stubborn as stone—was the only person I ever trusted with my life. We came home from the jungle in ’72 carrying the war in our nerves, and the world felt too bright, too loud, too polite to be real. So we disappeared into the Oregon Cascades, into a stretch of foothills locals swore was cursed. They whispered in diners about a hairy man who stole children and snapped elk necks like twigs. We laughed. We’d looked death in the eye and didn’t blink. We thought if the forest had a monster, it should be afraid of us.

Now, through the rain, I can see the headlights of black SUVs parked just beyond the property line. They’re not local. They’re waiting with the patience of paperwork and power—waiting for probate, waiting for doors to open, waiting for me to die or slip. Maybe they finally know what we dragged out of Devil’s Staircase back in ’87. Maybe they always knew and were only waiting for Miller’s heart to stop.

I’m recording this because the truth deserves to exist for at least one breath before they erase it. We didn’t kill the monster. We didn’t release it. We did something worse, something unforgivable in a way that only feels clear now.

We saved it.

Chapter 2 — The Pit in Devil’s Staircase

It started like a hunting trip, the way so many tragedies do—ordinary intentions, bad weather, two men too proud to ask for help. For three weeks something had been coming down from the ridge and tearing through Miller’s perimeter fence as if the wire were wet string. It ripped the steel door off the generator shed. It mauled two hunting dogs and didn’t even eat them. Just broke them, like a child breaking toys in a tantrum. We assumed bear. Maybe grizzly. Either way, we decided the old rules applied: identify the threat, neutralize it, go home.

Devil’s Staircase was the kind of terrain that eats confidence. No trails, just ancient mossed Douglas firs stacked close enough to blot out the sky, and a silence that didn’t feel peaceful. It felt pressurized, like the forest itself had learned to hold its breath. We found tracks—compression too deep for black bear. Miller knelt in mud, fingertips tracing crushed ferns, rain dripping from his boonie hat. “Whatever this is,” he whispered, “it’s heavy. Not three hundred pounds. This is… wrong.”

We dug a pit. Two grueling days in cold clay, eight feet down, six wide—an old soldier’s solution disguised as practical forestry. We didn’t spike the bottom. We weren’t trying to torture anything. We just wanted it contained long enough to decide whether to call the state or put a round behind its ear. We covered the pit with a lattice of weak branches, moss, and pine needles, and waited in a treestand while rain stitched the night together.

Hours later, the forest changed. Crickets stopped. Owls went silent. Even wind seemed to die. Then came a stride—two-legged, heavy, rhythmic. Crunch. Pause. Crunch. Pause. Not a bear’s shuffle. Not elk. Miller’s eyes widened in the dim moon-gray. He mouthed one word, barely air: Man.

Then the clouds broke for three seconds and the moonlight found the clearing.

It stood at the edge of our trap—eight feet of muscle and shadow, shoulders too wide, fur soaking light. A conical head seemed to sit directly on its shoulders like it didn’t need a neck. I remember my heart hammering so hard it felt like it might crack ribs. I remember forgetting the rifle in my hands because my brain couldn’t file what it was seeing into any category that let me breathe.

It took one step too many. Branches snapped. Gravity did the rest.

The sound it made when it fell still wakes me up decades later. It wasn’t a roar. It was a scream—human, shocked, afraid, in pain—echoing off canyon walls like a siren. Then a whimper, thin and pathetic, the sound of something that didn’t understand why the world had betrayed it.

We climbed down fast, boots tearing bark, flashlights cutting rain. I expected rage. I expected a violent animal slamming its way out. What I saw in that mud pit rewired my understanding of the world.

It was huddled in the corner, clutching its knee, shielding its eyes from the beam like a person. Five-fingered hand. Nails. Skin like cured leather. Amber eyes the size of saucers—intelligent, terrified, pleading. It pointed at its broken leg and made soft clicking sounds like a language trying to become a request.

It was asking for help.

Chapter 3 — The Helicopter With No Lights

Miller whispered, voice shaking, “Look at his face, Jack. It’s a man.”

Then the night broke open with a sound we knew better than prayer: rotors. Whoop-whoop-whoop, low and fast, blacked out, no navigation lights, hugging the treeline like a predator stalking prey. A searchlight swept the forest two hundred yards east, slicing through the rain. They were grid-searching. Closing.

Miller’s grip on my shoulder felt like steel. “They’re tracking him,” he shouted over the rising roar. “They aren’t looking for us. They’re hunting him.”

That was the moment our choices shrank to two brutal options: leave it in the pit and let the black helicopter take it, or do something insane. Miller didn’t hesitate. He slung his rifle and slid down into the mud with the creature like he was stepping into a firefight. I screamed his name, but he was already there, hands up, palms open, approaching the titan the way you approach a frightened dog.

“Easy,” he said, voice calm in a way only war can teach. “We ain’t the ones you need to worry about, but we gotta move.”

The spotlight kept sweeping closer. We had minutes. I ran for the tow strap and block-and-tackle we used for hauling elk. No Jeep—too loud. I lashed an anchor line around a Douglas fir and threw the end down. Miller looped the strap under the creature’s arms, talking constantly, keeping it from panicking. The torso was so big the strap barely reached. Its skin radiated heat like a furnace. It smelled of wet earth, musk, and something metallic like copper.

When I hauled on the tackle, the weight didn’t move. It was like trying to drag a Volkswagen out of a swamp. Then the creature understood. It planted its good leg, gritted flat human-like teeth, and pushed while I pulled. Together we got it over the lip of the pit.

Rotor wash hit us. The spotlight shattered into a thousand beams through branches. We ripped emergency Mylar blankets from our packs, threw them over its body to scramble thermal, covered the shine with ponchos and brush, and lay in the mud beside it like we were hiding a god from another god.

The helicopter hovered overhead long enough to make time feel like punishment. Then the pitch changed and it banked away.

When it was gone, the creature looked at us with something that made me feel sick: gratitude. Like a soldier looking at the medic who just dragged him from fire.

Miller said, breathless, “We can’t leave him. They’ll circle back. He can’t walk. That leg is shattered.”

So we dragged nine feet of myth on an elk sled through the treeline, creeping with lights off, praying the forest would keep our secret one more night.

Chapter 4 — The Bunker Becomes a Sanctuary

We didn’t take it into the cabin. Miller’s paranoia had built us a gift years earlier: a retrofitted Cold War bunker beneath the property—reinforced steel door, concrete walls, independent ventilation. He’d imagined missiles. He’d prepared for men.

Instead, we slid a wounded legend down concrete stairs and slammed the steel door shut behind it, the locking wheel clanging like a verdict.

Under the harsh fluorescent bulb, it lay on cold concrete, breathing shallow, leg twisted at a sick angle. Miller knelt like a field surgeon. “Compound fracture,” he said. “Tib-fib. If we don’t set it, infection kills him in three days.”

I laughed, hysterical and hollow. “We kidnapped Bigfoot, Miller.”

“We rescued him,” Miller snapped. “You saw that chopper. If they get him, he ends up on a metal table by sunrise.”

We guessed at morphine dosages like men defusing a bomb. Too much, the heart stops. Too little, pain wakes him and a thrashing titan kills us by accident. We cleaned the wound with saline and betadine, splinted with scrap lumber and duct tape, listened to bone grind back into place with a wet crunch that echoed off concrete like a confession.

For three weeks we lived under that cabin like it was a ship at the bottom of the sea. We took turns sleeping upright, rifles across our laps, watching him. He ate everything—canned food gone in days—then we became poachers to keep him alive, hauling elk and deer at night like criminals feeding a secret. The strangest part was how he ate: not like a wolf, but with hands, deliberate, almost polite. And always—always—he left a small piece of meat near the door. An offering. A thank you.

One night he tapped my rifle barrel, mimicked “pop-pop,” then pointed at himself and made a cutting motion across his throat. He wasn’t naming the gun. He was asking if I would use it on him. I set the rifle down, held up empty hands, and said the only word I could make true: “No.”

He stared for a long time, then thumped his chest and rumbled a sound: “Gut.” His name, or his approximation of what we called him—the General. Later, he handed me a carved piece of wood: a crude raptor in flight, made with thumbnail chisels and patience.

Animals don’t make art. Animals don’t understand gifts.

That wooden bird was the moment the bunker stopped being only a cage. It became a covenant. Miller looked at it, jaw tight, and said quietly, “We can never let them find him.”

We thought the secret was contained.

We were wrong.

Chapter 5 — The Broadcast and the Siege

By 1994 the General was no longer the starving creature we pulled from mud. He was bigger, thicker, fur silvering across shoulders, presence filling the bunker like weather. And then the atmosphere changed—literally. One summer afternoon, I felt a heaviness in my chest, like standing in front of a subwoofer with the volume turned down. Coffee in my mug rippled. Dogs hid under the porch whining.

We went downstairs and found him standing, eyes closed, head tilted back, chest pumping in a rhythm that made my teeth vibrate. He was producing infrasound—below hearing but inside the body. When Miller shouted for him to stop, it ended instantly, nausea lifting like a spell breaking. The General looked sad and pointed north, then up, making a mournful coo.

“He’s calling,” Miller whispered. “He’s lonely.”

I didn’t believe anything could hear through ten feet of dirt and concrete. Two days later, Sheriff Henderson showed up with a missing hiker report and stories of livestock panicking, headaches, fear waking people at night. He mentioned snapped trees shoved upside down into the ground like warning stakes—markers we knew our prisoner couldn’t have made.

When the sheriff left, Miller traced a line on the county map and went pale. “He wasn’t broadcasting into the void,” he said. “He was broadcasting a location.”

That night, in the silence where even crickets refused to live, I saw shapes at the treeline: a female, a juvenile—watching the cabin the way soldiers watch an outpost. Not attacking. Waiting.

We weren’t jailers anymore.

We were surrounded.

Chapter 6 — The Trade on the Porch

Miller’s solution was insane and correct: bring the General up, open the door, and negotiate—because search-and-rescue was coming with dogs and daylight, and daylight makes disasters official.

We opened the bunker. The General ducked into the living room, then onto the porch. Rain had eased into cold mist, moonlight thin through cloud. The female stepped out from the old oak, reddish-brown fur, leaner than the General, eyes intelligent and judging. A juvenile hovered behind her, nervous.

They spoke in trills and chest rumbles. The General answered, not with joy but with authority. He pointed to the sky, mimed rotors, pointed to the bunker, then made a sweeping motion—go. Leave. Stay away. He was ordering them to retreat because the world above was dangerous.

The female lowered her head in submission—then barked an order to the juvenile. He disappeared and returned dragging something that turned my stomach: a human body.

I raised my rifle. Miller pushed the barrel down. “Wait.”

The juvenile dragged the body to the edge of the clearing and left it there, then both Sasquatches vanished into trees like smoke. We ran. The hiker was alive—unconscious, wrapped in woven vines and moss, pupils blown wide like he’d been drugged. A hostage, a message, a trade.

We staged the scene a mile away to look like an accident and called it in anonymously from a payphone in town. By morning, the sheriff found the kid alive. Official story: confused hiker, fall, exposure, lucky break.

Unofficial truth: a tribe returned a human as proof they could have taken more—and as payment for the General’s obedience.

When I went to lock the bunker that night, the General sat on his blankets holding the wooden bird. He looked up at me. I left the bolts slightly unlatched. We both understood the lock was symbolic now. He could have left any time. He stayed because he believed it was protecting something—us, his kin, the fragile line between worlds.

And then decades passed, and the world got loud enough to see through trees.

Chapter 7 — The Storm Extraction

Technology killed our darkness. Trail cams. Satellites. Drones. Everyone carrying cameras like badges. We adapted like criminals: camo netting, odd jammers, hunting only at night. Then one crisp Tuesday a consumer drone hovered fifty feet above the cabin, gimbal eye pointed straight at the bunker doorway where I’d left it cracked for air.

Miller shot it out of the sky with a twelve-gauge. We destroyed the SD card. Burned the wreckage. But we didn’t know if it had live-streamed. That fear broke something in Miller that never healed. Six months later, he died in his chair and the black SUVs appeared.

The General knew. When I told him Miller was gone, he touched my face with a trembling hand. Then he pointed—not to the bunker door, but to the outside. For the first time in years, the old warrior returned behind clouded eyes.

He didn’t want to die in a cage.

So I chose a storm—the kind that grounds drones and smears thermal into chaos. I loaded my old Ford, hid him under a tarp like firewood, and drove past the waiting SUVs with my eyes locked forward and my heart trying to break free of my ribs. They didn’t stop me. Maybe they were waiting for a warrant. Maybe they wanted me to lead them.

At Devil’s Staircase, I untied the tarp and found him staring up at the trees like a man remembering his own name. He stood with effort, swayed, then drew in a breath and hummed the infrasound beacon—stronger than I’d felt in years—pouring what life he had left into a message the forest could carry.

I am here. I am home. I am dying.

When he collapsed, I cradled his head in my lap in the mud and waited.

The forest changed. Wind died. Birds stopped. Silence returned like a curtain dropping. Shapes detached from darkness—one, three, ten—gliding rather than walking, massive and quiet. A black-furred alpha stepped forward, looked at me, then at the dying elder. He nodded once, solemn, as if acknowledging a debt paid and a wrong corrected.

They lifted the General with tenderness that didn’t match their size. The General opened his eyes once, met the alpha’s gaze, then looked at me—no wave, no words—only a long final exhale.

They carried him into the deep timber and vanished.

I sat alone in rain, staring at the empty space where a forty-year secret had been, and understood the last cruelty of what we’d done. We hadn’t just hidden him from the government. We’d hidden him from his own kind. We called it rescue, but it was also imprisonment—sanctuary that turned into captivity because we were afraid of men in black helicopters.

Now the SUVs are waiting at my property line, and I don’t know if they’re coming for proof, revenge, or silence. All I know is that the General is finally home.

And I am the last man left holding the story.