When German Child POWs Saw American Ice Cream — Their Reaction Made Soldiers CRY

1) The Wire and the Water

Camp Perry, Ohio, June 1945. Lake Erie lay flat as hammered tin, a gray-blue mirror under a sky that could not decide between summer and sorrow. Inside the wire fence, seventeen German boys stood in the heat, faces hollowed by months of hunger, eyes older than their ages permitted. The youngest was fourteen. The oldest had just turned seventeen. They had fired rifles larger than their courage in the last, ragged defense of Berlin. They had slept in cellars that shook with artillery and woke to roofs that no longer existed.

.

.

.

Now an American sergeant walked toward them carrying something white and fog-breathed in paper cups.

Vanilla ice cream.

It seemed impossible, like a fairy tale object smuggled into a war zone. The boys watched, still as fence posts, as if any movement might scare it away.

They were Volksturm—the People’s Storm—conscripted in the war’s final months when Germany emptied its cupboards and found boys and old men where armies should have been. Klaus Zimmermann, fourteen, had been issued a uniform too big and a rifle too heavy, commanded to defend a city that had already fallen. Hans Bergmann, seventeen, had believed the posters and parades, had believed because disbelief felt like treason against his own future.

All of them had been taught since infancy who was superior and who was not; who deserved and who must be discarded. Now they were prisoners on an Ohio shoreline, fed and housed by the people they had been taught to fear.

On the crossing, a guard named Corporal James Mitchell—twenty-three, from a farm outside Bucyrus, Ohio—had watched the boys breathe like old men and speak like soldiers reciting someone else’s script. He had fought through France and into Germany and seen enough to know that mercy is not weakness. He had a younger brother at home, also fourteen, who worried about baseball tryouts. Looking at Klaus, small and silent, Mitchell felt the fence inside his chest bend.

Camp Perry was neat, squared by habits that survive any war. Prisoners were processed—showers, uniforms marked PW, medical exams that replaced guesswork with numbers. Colonel Robert Hayes, the camp commander, had orders: segregate the juvenile prisoners, educate where possible, treat firmly and humanely. The boys filed into Barracks 7 and discovered cots with real mattresses and windows with screens. After basements and cattle cars, it felt like something beyond luxury: it felt like safety.

That first afternoon, Colonel Hayes addressed them through an interpreter. “The war is over,” he said. “You will be treated fairly. You will work. You will learn. You will be repatriated when arrangements are made.”

Hans stood, defiance stretched to a cracking point. “We are soldiers of Germany,” he snapped in German. “We do not recognize this defeat. We will escape and return to fight.”

Hayes regarded him the way a father regards a son who has walked into a wall and insists the wall is wrong. “You are children,” he said. “Used by adults who should have protected you. While you are here, you will be treated with dignity. You will do the same in return.”

The days took shape: dawn inspection, barracks swept, breakfast in a mess hall where milk came in metal pitchers and bread had butter. Light work in the gardens and laundry. Afternoons in schoolrooms with chalk dust floating like a gentler kind of smoke. English lessons, civics, mathematics. A teacher named Mrs. Whitaker, whose son was in the Pacific, taught the alphabet to boys who could strip a rifle blindfolded.

Food undid them first. Calories at regular intervals are their own politics. Klaus gained ten pounds in two weeks; his face softened from angles back toward childhood. He still spoke little. Hans spoke too much, noisy with slogans that no longer fit the room. The others orbited between those poles—suspicious and relieved, craving and ashamed to admit it.

Mitchell walked the camp perimeter in the evenings, Lake Erie breathing in his ears. He found Klaus at the fence line, staring at water that went on and on, a thin boy in a borrowed uniform, holding his shoulders like a man twice his age.

“You speak English?” Mitchell asked.

Klaus shook his head. Mitchell tried his broken German. “Wie alt?” How old?

Klaus held up four fingers, then ten. Fourteen.

“Zu jung,” Mitchell said softly. Too young. He pointed toward the barracks. “Sicher.” Safe. He pointed at the lake. “Ohio.” He pointed at himself. “Mitchell.”

Klaus watched him with wary animal eyes and said nothing. But when he breathed, it sounded less like a held note and more like air.

2) Ice and Sugar

Major Sarah Caldwell arrived with a clipboard and a mind tuned to human fractures and repairs. A military psychologist assigned to evaluate prisoners, she had observed the boys with a clinician’s detachment and a mother’s ache. She watched them eat as if food might vanish in a blink. She watched them sleep in shocked stillness. She watched Hans talk and talk, a boy drowning in his own voice.

“Colonel,” she said to Hayes one evening, “we need to give them something that isn’t a rule or a ration.”

“Such as?”

“Ice cream.”

He blinked. “Ice cream?”

“It’s innocent,” she said. “Entirely non-military. Sweet, cold, unnecessary. A gift that says: you are a child. If we’re trying to reach the boy under the uniform, sugar will go where lectures can’t.”

Hayes saw quickly. A commissary run into town. A truck with dry ice. Ten gallons of vanilla, sweating with frost on a breathless afternoon while the lake lay flat.

Mitchell and three guards carried the tubs into the recreation yard. Paper cups. Wooden spoons. Boys gathered in a wary crescent, their bodies angled to flee and unable to move. Hans crossed his arms, jaw set. Klaus stood near the front, curiosity winning by a length.

Hayes’ interpreter kept it simple. “We thought you might like something cold. No conditions. Just ice cream.”

Mitchell dipped the scoop and carved out a round of winter. He tipped it into a cup and handed it to Klaus. “Langsam,” he said. Slow. He mimed a head-ache, grimaced, made the boys snort despite themselves.

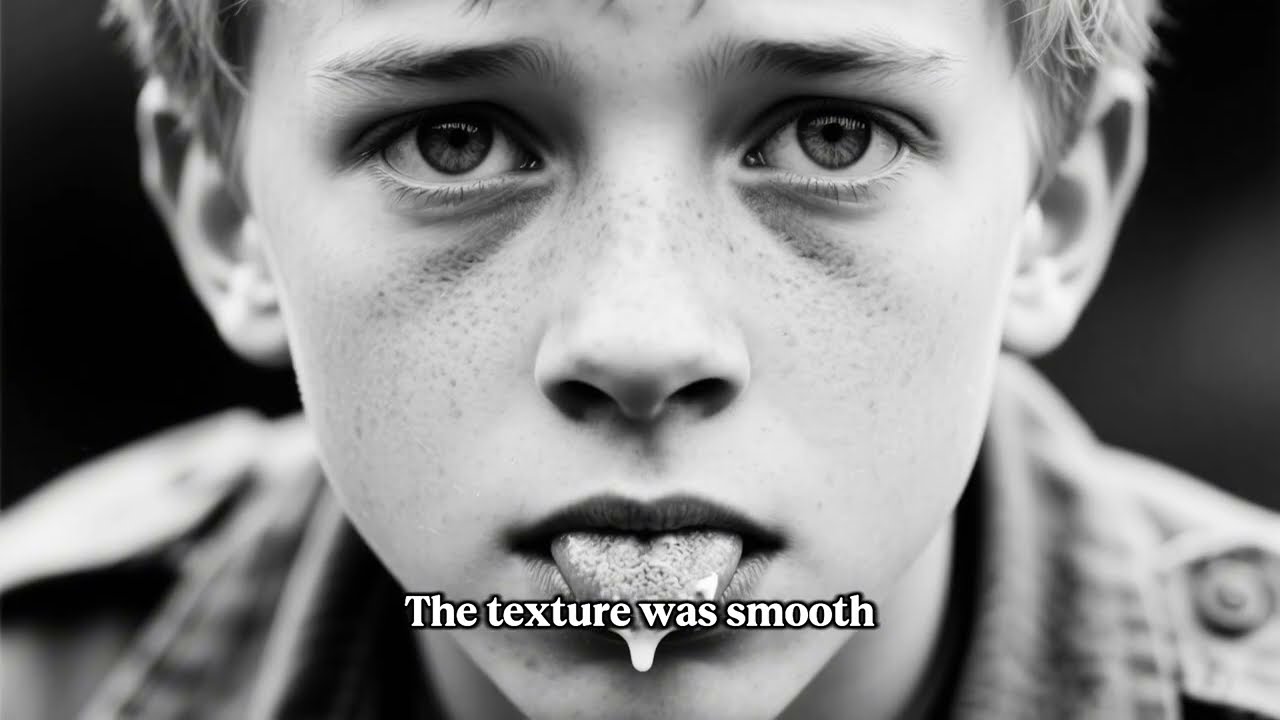

Klaus took the cup. He felt the cold through the paper. He lifted the spoon. He tasted.

Cold struck first—sharp, shocking, a clean pain. Then sweetness, full and unapologetic. Then the texture: smooth, melting, turning from solid to cream to memory. Klaus’ eyes widened. Something moved inside his chest with a violence that felt like breaking and mending at the same time. He made a sound like the beginning of a word and then, without any permission from his pride, began to sob.

Not polite tears. Not a few drops he could blink into his collar. Deep, wracking sobs that pulled his thin body into itself like a sail in a gale. He stood in the yard, wooden spoon dangling, cup shaking, and cried as if the world had finally granted him time.

The boys stared at him, then at the ice cream, then at the Americans. The guards froze, startled into stillness. Mitchell took a half step; Caldwell touched his sleeve. “Let it happen,” she whispered. “Let it come out.”

Klaus cried for everything the ice cream was not and everything it suddenly represented: for basements and rubble and neighbors’ voices forever gone; for hunger that gnawed and orders that shouted; for the night he had watched a building fold and a hand stick out of dust and a voice call once, then not again. He cried because kindness hurts when you have learned to live without it. He cried because frozen vanilla tasted like a world where adults give children treats instead of rifles.

One by one, the other boys stepped forward. They took cups with hands that trembled from malnutrition and caution. They tasted and discovered that the universe contained flavors beyond fear. One by one, they began to cry.

Hans waited longest. He watched his comrades. He watched the guards watching them. His pride stood like a sentinel and argued with his hunger. Finally he stepped forward and took a cup from Mitchell. He tasted. His jaw clenched as if to hold everything in, then loosened. He sat hard on a bench, cup in his lap, head in his hands, and wept for the boy he had been before men in uniforms taught him to chant.

The guards stood witness. Some wiped their eyes and did not pretend they weren’t. Mitchell took off his glasses and pinched the bridge of his nose. Corporal Davis, who had believed combat had drained him of tears, found he was wrong. Even Colonel Hayes felt his throat tighten against the strict lines of military bearing.

For twenty minutes, the recreation yard resounded with a sound the war had tried to erase: boys crying without shame. Vanilla melted uneaten in some cups. In others it was swallowed between sobs. Caldwell watched, noting physiological cues and cataloging breakthroughs and knowing none of that captured the truth: that human beings had remembered how to feel joy and grief at the same time.

3) After the Thaw

That night the barracks was quieter and louder all at once. Quieter because the constant hum of defensive talk had cut out; louder because real voices had replaced slogans.

Klaus sat beside Hans, the youngest and the oldest tied together by something they could barely name.

“I don’t understand why they are kind,” Hans said, his voice raw.

“Maybe,” Klaus said in careful German, searching for words he had never needed, “we were wrong about them.”

“Wrong about Americans,” Hans said, the words like stepping onto a bridge that might not hold. “Wrong about many things.”

Across the room, Ernst—fifteen, once a choirboy—spoke. “My father told me before I left: people are people first and enemies second. He said to remember that, even if it got me killed.”

“The regime called that defeatism,” Hans muttered, but without heat.

“The regime lost,” Ernst said. “Maybe defeatism was just truth.”

Mitchell poked his head in during rounds. The interpreter—a corporal from Cincinnati whose grandparents still prayed in German—was beginning to work himself out of a job. The boys asked questions about ice cream: was it common? Did American children eat it all the time? Did it come in flavors? Did Mitchell have a family? Did his mother make things that tasted like home?

Mitchell answered. “Ice cream is summer in a bowl,” he said. “Yes, kids eat it often. There’s chocolate and strawberry and something called butter pecan. My mother bakes pies. My brother plays baseball. He worries about small things like a decent person should.”

He paused, then chose his words like a man placing stones in a river, to make a crossing. “What happened to you was not your fault. Adults made the decisions. They handed you weapons and told you to carry their mistakes. The ice cream wasn’t charity. It was a reminder: childhood is supposed to have sweetness. You deserve some.”

Klaus spoke in halting English. “Thank you for seeing us not as enemy. As boys.”

“That’s what you are,” Mitchell said. “That’s what you should have been allowed to be.”

The changes came like summer on the lake—slow, then all at once. In class, hands went up. Hans, who had argued with every word in June, asked for books about democracy in July. He read about checks and balances, about laws stronger than men. He marveled that power could be made to answer questions. It shook him to realize he had been taught to worship power that answered none.

Mrs. Whitaker taught American history honestly: slavery and civil war, suffrage and strikes, triumphs complicated by failures. The boys had been taught to think of democracy as chaos. They began to see that its messiness was its guardrail.

Professor Martin Herschel arrived for a week in August. He had fled Germany in the 1930s and taught political philosophy at Kenyon College now. He spoke to the boys in fluent German about what they had been taught and what was true.

“You were told the strong must rule,” he said. “This is a half-truth. The strong often do rule. It is not the same as ‘must.’ You were told that people come in ranked kinds. That was a lie so useful to cruel men it almost became true. Your job now is to unlearn: to build a life where no one with a smooth story can steal your mind.”

Hans raised his hand. “How do I forgive myself for believing?” he asked, voice tight as wire.

“By refusing to keep doing it,” Herschel said. “By living differently. You were a child in a storm. Now you are old enough to decide which way to walk.”

The Red Cross found strings that still connected Germany to its scattered children. Letters arrived, written in cramped hands on paper salvaged from wreckage. Klaus learned his mother and sister had survived Berlin and were lodged with cousins in Bavaria. His father was missing on the Eastern Front—an absence that meant, in most cases, forever.

He wrote back in precise German. Mother, I am safe by a lake in America. They give us food and teach us. I am learning English. I am learning other things too. I am learning that much of what we were told was not true. I will be different when I come home. I hope that is not a disappointment.

Hans wrote to Hamburg and confessed—not crimes, but credulity. Father, I believed what I wanted to believe because the alternative was unbearable. I am learning to bear it now.

4) Songs and Games

A USO troupe rolled through in late July and set up a small stage under sycamores. Guards and prisoners sat on benches and on the ground, the air warm and filled with a kind of expectancy that did not belong to the calendar.

A woman sang jazz with a voice like clean silk. The boys listened, stunned by a music banned as decadent. Then she sang “I’ll Be Seeing You,” and even those with little English understood longing in the long notes. Klaus thought of a farmhouse in Bavaria he had never seen, of a mother reading a letter by lamp light, of a sister who had lost her baby teeth in a city that no longer had street names. He did not cry this time. He let the sadness sit beside him like an old friend who had shown up without knocking.

That night in Barracks 7, Ernst taught them a German folk song—nothing martial, nothing grand. A song about spring. They sang softly at first, then with more confidence, voices weaving together in a fabric that had not existed for years. Mitchell stood outside and listened, cap in hand. It sounded like a door opening.

In mid-August, the guards organized a baseball game. The boys had never seen baseball, a geometry of grass and rules that made sense only inside itself. The guards taught them how to hold a bat, how to run through first base, why three strikes is both sentence and mercy.

They wore motley uniforms and too-big gloves. They laughed at their own mistakes, that pure laughter that only children possess and war had stolen. Klaus, to everyone’s surprise, could pitch. His anchor-thin frame hid a slingshot arm. He learned a curveball—a small miracle of physics—and when he threw it to Mitchell in the seventh inning, the ball bent like a sentence, and Mitchell swung through air.

Klaus pumped his fist, then looked stricken at his own joy, as if it were contraband. “That’s it,” Mitchell called in German, grinning. “You’ve learned too well.”

For a moment, labels fell away. They were just boys and young men on a summer afternoon with dust in the light and the game moving them around like planets.

5) Lessons with Edges

Caldwell did not let sweetness replace truth. In discussion sessions, she asked hard questions. What had they known? What had they suspected? What had they chosen not to see?

“I didn’t know,” Hans said once, then swallowed. “Or—I knew some things and told myself they were lies from the enemy. I liked the strong stories. They told me I was part of something great. I did not want to hear anything smaller and truer.”

“You were a child,” Caldwell said. “Children are built to believe the people who feed them. But you are not a child forever. What you do with what you know now—that is on you.”

The boys cried again, differently than in the yard. Not because sweetness sharpened sorrow, but because truth asked them to carry weight. They did not flee from it. They squared their shoulders.

By September, repatriation orders began to arrive. The classes intensified, as if teachers could pour a semester into a month. Herschel gave them a farewell like a benediction. “You will go home to a ruined country,” he said. “Please remember that ruin can be a field, not only a grave. Plant what you have learned. Do not be fooled by anyone who offers a single, simple answer. Those are the most dangerous lies.”

Care packages went into duffels: socks, sweaters, tins of meat, paper and pencils. More precious were the letters: notes of reference signed by officers and teachers attesting to character and conduct. Proof that they had learned, that they had changed, that they were more than the uniforms they had been shoved into.

Mitchell pressed a baseball into Klaus’s hands, the leather scuffed and the white smudged with eighty fingerprints: guards, teachers, prisoners, even the colonel. Names crowded the seams.

“Remember,” Mitchell said. “That enemies can become teammates. That the game goes on after the war stops.”

Klaus cradled the ball as if it contained glass. “I will never forget,” he said in English that had become steady. “The ice cream. The baseball. The way you saw me.”

6) Homecomings

On an October morning the trucks rolled out of Camp Perry. Guards lined the fence. Officers saluted. The boys sang as they went—not marching songs, but Ernst’s song about spring. The sound lifted over the wire and the lake and the highway, something human carried by wind.

Germany greeted them with rubble and ration cards, with streets where only basements remained to indicate addresses, with lines for bread and questions without answers. The regime’s crimes were becoming facts no one could deny. Tribunals began. The nation looked in a mirror and did not recognize its face.

Klaus found his mother and sister in Bavaria, living with three other families in two rooms of a farmhouse. His father was listed as “missing, presumed dead.” Klaus found work as a translator for the occupation authorities, English unspooling from his mouth like a rope thrown across a chasm. Later he became a teacher—English and civics—standing in front of boys who were not much younger than he had been and insisting that slogans are not lessons. He kept the signed baseball on his desk. When a student asked about it, he told the story of the day ice cream made him cry.

Hans returned to Hamburg—shells of brick, a city reassembled from pieces. His father, who had been a small man in a dangerous system, faced questions from a British tribunal. Hans told the truth about what he had believed and why he had stopped. He studied law. He worked inside Germany’s new structures, the ones designed to keep any man from becoming the state.

Ernst became a musician, chasing the sound he had heard from the USO stage. He played in clubs and concert halls, jazz and Schubert, improvisation and order, proof that art can be a kind of resistance to forgetting.

Of the seventeen boys who cried over ice cream, most survived the tight, hungry years. They married and raised children who learned English in school and never wore uniforms before their voices changed. They grew old in a country that bickered and built, that tied itself to neighbors rather than enemies.

They remembered.

7) The Lesson That Melted Slowly

It is easy to dismiss ice cream as trivial. It melts. It is sugar and milk and air. It is not policy or strategy or an argument in Parliament. But in a yard at Camp Perry on a breathless day in June 1945, it was a lever that moved something heavy.

Caldwell’s insight was deceptively simple: to reach the boy under the soldier, hand him something that belongs to childhood. A sweet, cold gift without conditions. A sensory assertion that another world exists. The vanilla cut through propaganda faster than any pamphlet. It reached the limbic brain—the place where fear lives—and brought a different message: you are safe.

The American soldiers who stood with tears on their faces were not being sentimental. They were witnessing the damage done when adults weaponize children—and the possibility that kindness can begin to repair it. They were, in that moment, doing something worthy of praise: honoring their country’s strength by using it to protect rather than punish. They proved that discipline and compassion can be the same muscle.

Decades later, when Klaus showed that baseball to his students, he was not telling a story about dessert. He was telling them how to live after catastrophe: question loud men; cherish small mercies; refuse to reduce any human being to a label that makes cruelty easier. He was telling them that American guards in a hard year chose to treat enemy boys as sons and, in doing so, helped those boys become men who would not repeat the past.

The ice cream melted in minutes. The lesson did not. It lingered, cooling tempers, sweetening possibilities. It crossed classrooms and kitchens, parliaments and playgrounds. It turned seventeen boys back into children for just long enough to change the angle of their lives.

The war had taught them to hate. Ice cream taught them they could still feel joy.

Between those truths lay the path they chose—toward a future built not by fear, but by the steady work of people who remember that power means restraint, that victory means responsibility, and that the measure of a soldier is not only how he fights an enemy, but how he treats a child.