Why a U.S. Soldier Tore the Dress of a Japanese Women POW — What He Revealed Stunned All

The Mercy Cut

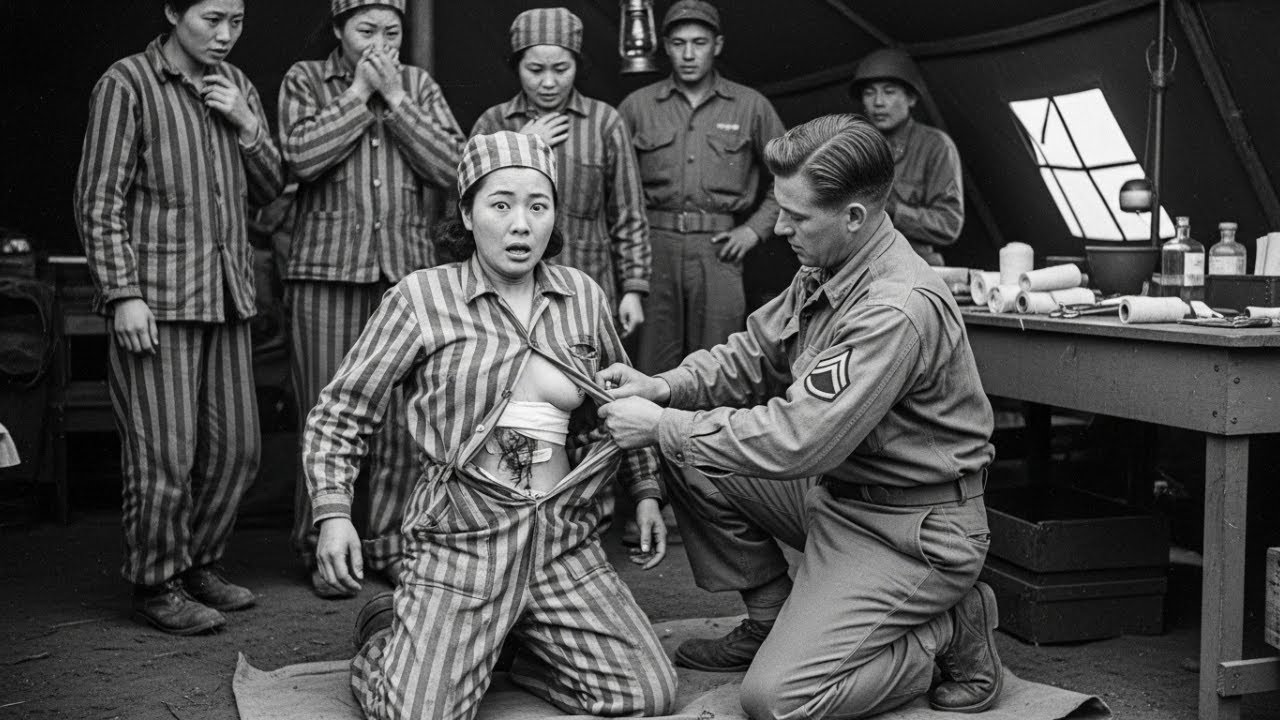

The photograph sat in a manila folder, buried for decades among thousands of declassified documents in the National Archives. Black and white, grainy, and jarringly ambiguous, it depicted a large American soldier in a bloodstained uniform towering over a kneeling Japanese woman. His hands gripped the fabric of her traditional kimono, tearing it away as her face contorted in anguish, tears streaming down her cheeks. Other soldiers watched from the periphery. One held a camera.

.

.

.

For thirty-three years, the image remained sealed in classified military files. When historian Dr. Margaret Fleming discovered it in 1978, her first thought was that she had stumbled upon evidence of a war crime. The composition suggested violence, violation, an abuse of power so blatant that even wartime could not excuse it.

But Dr. Fleming was trained to look beyond first impressions. She read the accompanying documentation—medical notes, witness statements, a timeline that reconstructed every moment of June 15, 1945. Slowly, impossibly, the truth revealed itself. The photograph, which appeared to capture humanity at its worst, actually documented humanity at its best. The torn dress was not an act of cruelty, but of mercy so profound that it would echo across eight decades, touching thousands of lives and changing how we understand compassion in the crucible of war.

To understand that moment, we must first meet the two people whose lives collided on that sweltering June day in Okinawa: an Iowa farm boy who carried his mother’s Bible into battle, and a Japanese nurse taught that Americans were monsters. Their story began not with violence, but with letters from home.

Camp Hansen, Okinawa, June 14, 1945

The Battle of Okinawa had ended just two weeks earlier, leaving over 100,000 Japanese military casualties and forcing thousands of civilians and soldiers into American custody. The camp was hastily constructed, overcrowded, and stretched the resources of the occupying forces beyond their limits.

Sergeant Thomas Bishop sat on an empty ammunition crate outside the supply tent, reading a letter that had taken six weeks to reach him from Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The paper was worn soft from being folded and unfolded, carried in his pocket over his heart.

Tommy, the letter began. She was the only person who still called him that. Spring planting is done. Ruth and I managed most of it ourselves, though Mr. Peterson from the next farm helped with the heavy equipment. The cows are healthy, and we got good prices for milk this month.

Tom closed his eyes, picturing the farm. Red barn that needed painting. Cornfields stretching toward the horizon. His sister Ruth, nineteen, probably wearing their mother’s old work boots because she refused to spend money on herself. They were keeping the place running without him, without his father, who had died in a tractor accident in 1941, leaving Martha Bishop a widow at fifty, with a farm to maintain and two children to raise.

That accident was why Tom had enlisted. Military pay was regular. It meant his mother and sister could hire help during harvest. It meant they could keep the land his grandfather had homesteaded. It meant Ruth might even go to teachers college like she wanted. But it also meant three years in the Pacific Theater. Three years of watching good men die in ways that made no sense. Three years of becoming someone his mother might not recognize.

I pray for you every night, son. Remember what I told you before you left. War will try to turn you into something you are not. Do not let it. Stay the good boy I raised. Come home to us with your soul intact.

Tom felt the weight of those words. Soul intact. Was that even possible? After Guadalcanal, after Saipan, after Okinawa? His best friend Carl Henderson had died at Saipan, stepping on a mine meant for Tom. Carl had looked back at him and said, “Take care of my ma, Tommy. Tell her I wasn’t scared.” Then the explosion.

Tom had written that letter to Carl’s mother. He had lied and said it was quick, that Carl hadn’t suffered. He had lied and said Carl had been brave. The truth was, Carl had been terrified. They all were. But what else could Tom write? That her son had died screaming? Some truths were too heavy to share.

Tom smiled despite himself. The promise of home, of a meal cooked by his mother, of fried chicken and apple pie—something worth surviving for. All my love, Mama.

He folded the letter carefully and returned it to his pocket. He was twenty-seven years old, six foot two, two hundred ten pounds of muscle built from farm work and military training. His hands were permanently calloused, dirt embedded under his fingernails no matter how hard he scrubbed. A shrapnel scar ran across his right forearm from Saipan. His face carried lines that belonged to a much older man. But when he read his mother’s letters, he was still Tommy, the boy who had chased chickens around the yard, who had cried when his father died and thought the world would never make sense again.

The war had tried to turn him into something else, something harder, something capable of killing without hesitation. And it had succeeded, at least partially. Tom was a good soldier. He followed orders. He did his duty. But his mother’s voice in those letters kept reminding him that duty was not the same as righteousness. That following orders was not the same as doing what was right. That being a good soldier and being a good man were sometimes two different things.

He looked toward the prisoner compound. Hundreds of Japanese prisoners moved behind the chain-link fences topped with barbed wire. Soldiers, civilians, women, children, old men—all of them caught in the machinery of a war they probably never wanted. He watched an elderly Japanese woman share her meager rice ration with a young girl, perhaps her granddaughter. The gesture was so simple, so human, that it cut through all the propaganda and training. These were not faceless enemies. They were people. People who loved their families, who wrote letters, who worried about the ones they had left behind.

In the Women’s Section

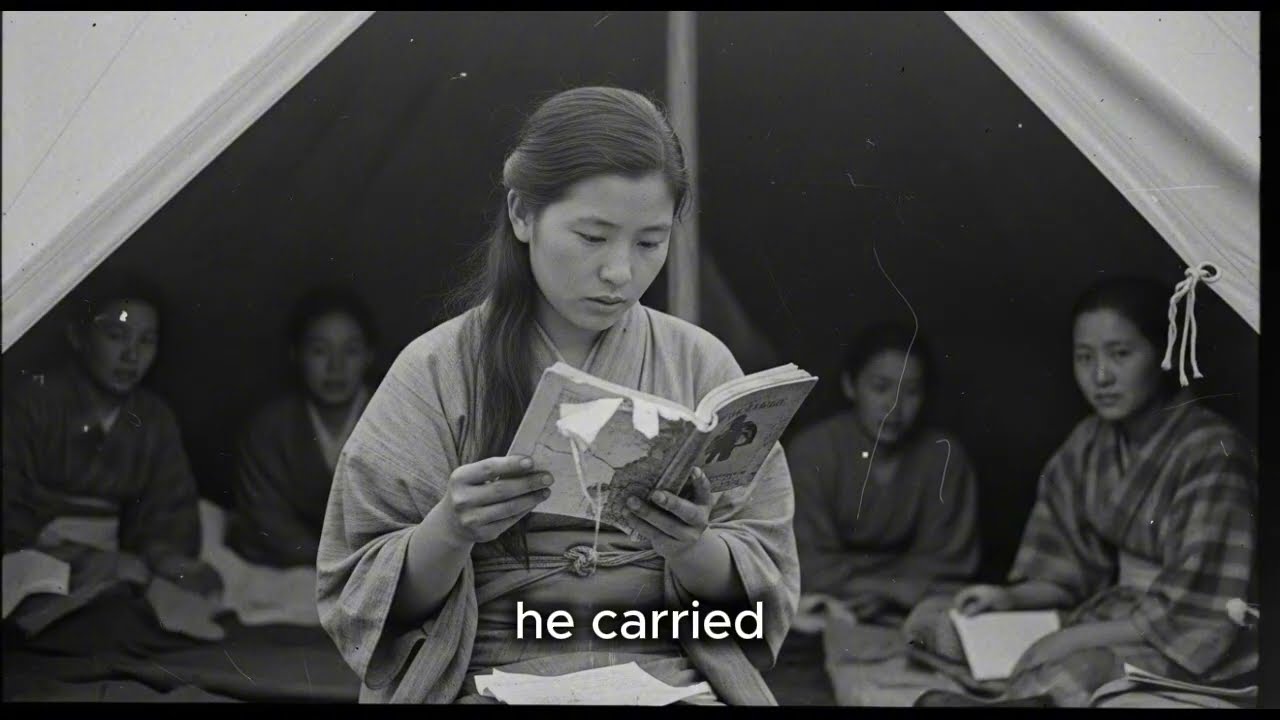

Yuki Nakamura sat in the shade of a canvas tent, trying to focus on a damaged medical textbook. The book had survived the battle that killed her father. She had hidden it in her belongings when American forces overran the field hospital where she had been working. It was one of the few things she had managed to keep.

Yuki had been studying medicine since she was sixteen, taught by her father, Dr. Takeshi Nakamura, a civilian physician in Naha before the war. He had dreamed his daughter would attend medical school in Tokyo, something almost unheard of for women, but he had believed in her intelligence and dedication.

Now, her father was dead—killed in an American bombing raid in April. Her mother was dead. Her younger brother, Kenji, only seventeen, had been drafted into the Imperial Army and was presumed dead. Yuki was twenty-four years old and completely alone in the world.

She had been a nurse in a field hospital, treating wounded Japanese soldiers and occasionally captured Americans. She had treated both with equal care because that was what her father had taught her. A patient is a patient. Suffering does not have a nationality.

When American forces overran the hospital on May 22, Yuki had expected to be killed. She had been taught that Americans were devils, that they tortured prisoners, that they raped women and murdered children, that death was preferable to capture. But three weeks in American custody had contradicted everything she had been told. The Americans gave prisoners adequate food—rice, canned vegetables, sometimes canned meat. It was not luxurious, but it was regular and sufficient. No one was starving. There was no torture, no systematic cruelty. Guards were stern, but not brutal. They followed regulations that seemed to prioritize basic human dignity.

Yesterday, Yuki had witnessed something that shattered her understanding completely. She had watched an American guard, a young man barely out of his teens, give his ration cookie to an elderly Japanese woman who was struggling with hunger. He had done it quietly, without seeking recognition or reward. He had simply seen suffering and acted to relieve it.

This was not the behavior of devils. This was not the behavior of an enemy committed to extermination. Yuki did not understand. The propaganda had been so certain, so absolute. Americans were monsters who would make prisoners suffer. But the reality was different. Not perfect, not comfortable, but fundamentally decent. It created a cognitive dissonance that Yuki struggled to resolve. Had her own government lied to her? Or was this camp an exception?

That evening, as the sun set over Okinawa, Yuki felt a dull ache in her lower right abdomen. She tried to ignore it. Probably bad food, probably stress. But by morning, the ache had sharpened into pain. Persistent, localized, familiar. Yuki had enough medical training to recognize the symptoms. Appendicitis, early stage, but progressing. Without treatment, the timeline was predictable: twenty-four to forty-eight hours before the appendix ruptured, then peritonitis, then sepsis, then death within three to five days.

She needed surgery immediately. But how could she communicate this to her captors? The guards did not speak Japanese. She knew only a handful of English words, mostly medical terminology. And even if she could make them understand, would they care? Would they waste precious medical resources on an enemy prisoner?

Yuki pressed her hand against the source of pain and felt fear settle into her bones. She was going to die here, alone, far from home, in a prisoner of war camp where no one would mourn her—unless she found a way to make someone understand.

The Medical Tent

Nurse Ellen Cooper had been in the Pacific theater for two years, moving from island to island, treating wounded Marines and soldiers under conditions that would have seemed impossible back home in Georgia. At thirty-one, she had developed a reputation for fierce competence and unexpected compassion. She had seen enough death to understand its inevitability, but she fought against it anyway because that was what nurses did.

Ellen had lost her fiancé at Pearl Harbor. Robert had been a young naval officer stationed on the USS Arizona. When the Japanese attacked, Robert had died in the initial explosion, his body never recovered. Ellen had enlisted the day after his funeral, not for revenge or hatred, but because she understood that war created suffering on all sides, and someone needed to be there to alleviate it. Medical care did not take sides. Pain did not recognize nationality. Ellen believed healing was a calling that transcended politics.

On the morning of June 15, 1945, Ellen was conducting her daily health inspection of the women’s section of the prisoner compound. She noticed a young Japanese woman doubled over near one of the tents, her face pale, sweat soaking through her clothing despite the shade. The woman was clutching her abdomen, breathing in short, shallow gasps.

Ellen immediately shifted into clinical mode. She knelt beside the woman and spoke slowly in halting Japanese. “Desuka? Where does it hurt?” The woman pointed to her lower right abdomen and managed to say in careful English, “Appendix. Surgery. Or die.”

Ellen’s blood ran cold. She understood immediately. Appendicitis was a death sentence without surgical intervention. And this woman, whoever she was, had enough medical knowledge to self-diagnose.

Ellen placed her hand on the woman’s forehead. Fever, significant. She gently palpated the lower right quadrant of the abdomen. When she pressed down, the woman showed moderate discomfort. But when Ellen released the pressure, suddenly the woman screamed. Rebound tenderness. The classic sign of acute appendicitis.

This was a medical emergency. Without surgery, this woman would die. Not quickly, not mercifully. She would die slowly over several days as her appendix ruptured, spilling bacteria throughout her abdominal cavity, overwhelming her immune system, and shutting down her organs one by one.

Ellen stood up, her mind already racing through the logistics. They had a surgical tent. They had basic equipment. Lieutenant Hartwell was a trained surgeon. They could do this. But would Captain Crane approve? Would he authorize the use of precious medical supplies on an enemy prisoner? Ellen did not know. But she knew one thing with absolute certainty. She had taken an oath. She had promised to care for the sick and injured. And that oath did not include exceptions for nationality.

The Mercy Cut

By noon, the medical tent had been transformed into a makeshift operating theater. Nurse Ellen Cooper worked with practiced efficiency, laying out surgical instruments. Lieutenant Hartwell scrubbed his hands and forearms with harsh soap and precious antiseptic solution. Private Daniel Reeves stood in the corner, checking his camera equipment. His job was documentation—official military photography, recording events for the historical record.

Sergeant Tom Bishop arrived last, summoned from his patrol duties with minimal explanation. When he entered the medical tent and saw the preparations, he understood immediately that something significant was about to happen, something that required witnesses.

Hartwell turned to face him, his expression grave. “Sergeant, we are performing emergency surgery on a Japanese prisoner. I need you here as an official witness. If the patient struggles during the procedure, I will need you to help restrain her.”

Tom felt cold understanding settle into his chest. Restrain? Why would she struggle?

“We have minimal anesthesia. She will be conscious for portions of the surgery. She will feel pain, possibly extreme pain. If she moves at the wrong moment, I could sever an artery or puncture an organ. I need her absolutely still.”

Tom looked at the stretcher where the young Japanese woman lay, her face pale with pain and fear. She was small, perhaps five foot three, maybe a hundred pounds. She looked younger than her years, vulnerable in a way that made Tom think of his sister Ruth.

“I want you to help save her life,” Hartwell replied quietly. “I know how this sounds. I know how it feels. But without your help, she dies. With your help, she has a chance.”

Sometimes the right thing felt wrong. Sometimes mercy looked like violence. Sometimes being good meant getting your hands dirty.

“I will do it,” Tom said.

Ellen brought Yuki into the tent on a stretcher, moving carefully to avoid jostling her. Yuki’s eyes were half closed, her breathing shallow and rapid. The fever had climbed higher. Ellen tried to explain what was about to happen using her limited Japanese and elaborate hand gestures. Surgery. Pain. But life, survival, hope.

Yuki understood enough. She was a nurse. She knew what appendicitis meant. She knew the timeline. She knew that without surgery, she would die slowly and painfully. So when the Americans moved her to the medical tent, when she saw the surgical instruments laid out, when she understood what they intended to do, she felt both terror and desperate hope. Terror at the pain that was coming. Hope that she might survive to see another day.

But then she saw the big American soldier enter the tent—the one with the tired eyes and the broad shoulders. The one who looked like he could break her in half without effort. And she felt a spike of pure fear. Was this how she would die? Would they say it was surgery, but really it would be execution? Would this soldier be the last thing she saw?

Tom positioned himself beside the stretcher, trying to make his presence less threatening. He caught Yuki’s eyes and saw the fear there. He wished he could tell her that he was not a monster, that he did not want to hurt her, that everything about this situation made him feel sick. But they did not share a language. All he could offer was his expression. He tried to make his face gentle, reassuring. He hoped it worked. He suspected it did not.

Hartwell encountered a problem he should have anticipated, but somehow had not. Yuki wore a traditional kimono, a complex garment with multiple layers, intricate ties, and wrapping. To perform surgery, Hartwell needed access to her lower abdomen. But he did not know how to remove a kimono properly. He did not understand the cultural significance of the garment or the profound humiliation that being undressed by male strangers would cause. And they did not have time for careful, culturally appropriate disrobing. The appendix was on a timer.

Hartwell made a decision that felt necessary and terrible in equal measure. “We will have to cut it just enough to expose the surgical site,” he said. “Sergeant Bishop, I need you to do it.”

Tom stared at him. “Why me?”

“Because I need my hands free to operate the moment we have access. Nurse Cooper needs to assist me. Private Reeves needs to document. You have steady hands and the physical strength to make it quick and clean.”

Hartwell held out a pair of surgical scissors. “Cut from the hem upward. Expose the lower right quadrant. Try to minimize the damage to her clothing. Be as respectful as possible given the circumstances.”

Tom took the scissors. They felt impossibly heavy, heavier than any rifle he had ever carried. He looked at Yuki lying on the stretcher, looking up at him with eyes that held terror and resignation. Ellen knelt beside Yuki and spoke in halting Japanese, trying to explain. They needed to cut her clothing. It was the only way. They were sorry. So sorry.

Yuki understood. Her body went rigid. In Japanese culture, modesty was not just preference. It was identity. To be exposed, to have her clothing removed by men, was a violation that transcended the physical. It touched something fundamental about who she was. She wanted to refuse, wanted to scream that she would rather die than endure this humiliation. But she was also a pragmatist. She was a nurse who understood medical necessity. And she was a young woman who did not want to die at twenty-four. So she closed her eyes and nodded. Permission, not consent. Surrender to necessity.

Tom knelt beside the stretcher. His hand touched the fabric of the kimono, and he could feel Yuki trembling beneath it. He thought about his mother, about his sister, about every woman he had ever known who deserved to be treated with dignity and respect. And then he thought about the alternative—about Yuki dying in agony over the next several days because he had been too squeamish to do what needed to be done.

He positioned the scissors at the hem of the kimono and looked up at Hartwell one last time. The doctor nodded. Tom cut. The sound of tearing fabric filled the tent. Loud, violent, wrong.

Outside the tent, Japanese prisoners heard that sound and began shouting. They did not understand the context. They only heard a woman’s clothing being torn. The implication was immediate and terrible. Guards moved to form a perimeter, preventing prisoners from approaching the medical tent. Voices rose in protest. Some prisoners were crying. Others were shouting accusations in Japanese that the guards could not understand, but whose meaning was unmistakable.

Inside the tent, Yuki made a sound that was not quite a scream. It was deeper, more primal—the sound of someone whose dignity was being stripped away along with her clothing. Tom worked as quickly as he could, cutting upward along the seam, trying to expose only what was necessary. The kimono fell away, revealing Yuki’s swollen abdomen. The skin was hot to the touch, stretched tight over the infection beneath.

Reeves’s camera shutter clicked. Once, twice, three times. The photographs captured the moment: a large American soldier, hands gripping torn fabric; a Japanese woman on a stretcher, face contorted with distress; other soldiers watching. Out of context, the images looked exactly like what everyone feared they showed: brutality, violation, the abuse of power. But Reeves was careful—he photographed from multiple angles, capturing Hartwell preparing instruments, Ellen adjusting surgical drapes, the medical setting, the clear evidence of emergency intervention. Context. The photographs needed context.

Ellen moved immediately to preserve what modesty remained. She draped surgical sheets over Yuki’s body, covering everything except the surgical site. The sheets were clean, stark white, professional. They transformed the moment from violation to medical procedure.

Tom stood up, still holding the scissors, his hands shaking now that the action was complete. He felt soiled, guilty, as if he had crossed a line that could never be uncrossed.

Yuki lay on the stretcher, tears streaming down her face, her body rigid with humiliation. She kept her eyes closed, unable to look at the men who had just stripped away her dignity. But Ellen took Yuki’s hand and held it firmly. She spoke in Japanese words she had practiced. “Daijoubu. It’s okay. You are safe.”

Yuki opened her eyes and looked at Ellen. The nurse’s face held nothing but compassion. No judgment, no cruelty, just a professional determination to help. And slowly, Yuki’s breathing began to steady. Not because the humiliation was less, but because she understood finally and completely that these people were trying to save her life.

The Operation

Hartwell injected the local anesthetic in a circle around the surgical site, giving it two minutes to take effect. It would numb the immediate area. It would not eliminate pain. It would only make the pain bearable. Maybe.

He made the first incision. Yuki screamed. The local anesthetic was not enough. Could never be enough. The scalpel cut through skin and Yuki felt it as a line of fire across her abdomen. Her body convulsed, instinct demanding that she escape the source of pain. Tom placed his hands on her shoulders, not brutally, not with excessive force, but firmly enough to keep her still.

“I am sorry,” Tom whispered, even though she could not understand. “I am so sorry. You are going to live. I promise you are going to live. Please just hold still, please.”

The surgery proceeded with agonizing slowness. Hartwell worked through layers of tissue—skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle. Each layer required careful cutting. Each blood vessel needed to be clamped or cauterized. Each movement was calculated to minimize damage while achieving access.

Blood welled up from the incision. Ellen dabbed it away with gauze, keeping the surgical field clear so Hartwell could see what he was doing. The smell of blood filled the tent, metallic and visceral. Yuki’s screams had subsided to continuous moaning. She was crying without sound, tears streaming down her face, her body shaking under Tom’s hands.

Tom kept talking to her. Meaningless words, comforting sounds. “You are doing so good. You are so brave. It is almost over. Just hold on. Just hold on a little longer.” He had no idea if his words helped, but they helped him. They gave him something to do besides feel like a monster.

Reeves continued documenting. His photographs captured the surgery in clinical detail—Hartwell’s hands steady and precise, Ellen’s assistance, Tom’s position holding Yuki’s shoulders, the clear evidence of medical procedure, not abuse. But Reeves’s hands were shaking. He had joined the military believing in truth and documentation. Now he was learning that some truths were harder to witness than others.

Hartwell reached the peritoneal cavity and carefully opened it. He could see the appendix now, and what he saw made his blood run cold. “Christ,” he muttered. The appendix was not just inflamed. It was gangrenous, black and swollen to nearly twice its normal size. The walls were beginning to break down, leaking purulent material into the surrounding tissue. They were perhaps an hour away from complete rupture, maybe less.

“Hold her absolutely still,” Hartwell’s voice was sharp with urgency. Yuki’s body convulsed in response to a fresh wave of pain. As Hartwell manipulated the infected tissue, Tom leaned his full weight onto her shoulders, pinning her to the stretcher as gently as he could while still maintaining control.

“I am sorry. I am sorry. I am sorry,” Tom repeated like a prayer or a penance.

Hartwell managed to get the appendix out intact. Barely. He lifted the diseased organ with forceps and dropped it into a metal pan. It landed with a wet sound, black and grotesque, clearly hours from rupture.

“Got it,” Hartwell said, his voice thick with relief. “Now I close her up and hope to God infection does not set in.”

But before he could begin suturing, Yuki screamed louder than before—a scream of pure agony that seemed to come from somewhere beyond human endurance.

Ellen checked her watch. “The local anesthetic has worn off completely. She is feeling everything now.”

Hartwell looked up, his face stricken. “I still have to close. I cannot leave the incision open. She will die from infection within days.”

“I know,” Ellen said quietly.

So Hartwell continued. He began suturing the peritoneum closed, then the muscle layer, then the fascia, working from the inside out. Each stitch required precision. Each movement caused Yuki pain that she could not escape. She was screaming continuously now, not words, just raw sound—the sound of suffering that had exceeded the capacity for language.

Tom was crying, tears streaming down his face as he held her shoulders, keeping her still enough for Hartwell to work. He kept talking, words tumbling out in English that she could not understand.

“I am sorry, God. I am so sorry. You are going to live. You are going to survive this. This is saving you. I swear it is saving you. Please believe me. Please forgive me. You are going to be okay. You are going to go home. You are going to have a life. Please just hold on. Please.”

Ellen was crying too, tears falling onto her surgical gown as she assisted, but her hands remained steady. She passed instruments to Hartwell without hesitation. She maintained the sterile field. She did her job even as her heart broke for the young woman suffering before her.

Only Hartwell’s face remained impassive, not because he did not care, but because if he allowed himself to feel what he was doing, his hands would shake. And if his hands shook, he might make a mistake. And mistakes in surgery killed people. So he compartmentalized. He became pure technique, pure focus. He was not causing pain. He was closing an incision. He was preventing infection. He was saving a life.

The surgery took another twenty minutes. Twenty minutes that felt like hours. Twenty minutes of Yuki screaming until her voice gave out and she could only make broken gasping sounds. Twenty minutes of Tom holding her, whispering apologies. Twenty minutes of Ellen assisting while praying silently. Twenty minutes of Reeves documenting everything with photographs that would either vindicate or condemn them.

Finally, Hartwell tied off the last suture. “Done. It is done.” He stepped back from the stretcher and his hands began to shake violently. All the tension, all the focus, all the suppressed emotion came flooding back now that precision was no longer required.

Yuki had stopped making sounds. She had passed out, her body simply unable to endure consciousness any longer. Her face was pale, covered in sweat, streaked with tears, but her breathing was steady, strong. Tom released her shoulders and stumbled backward. He looked at his hands. They had left marks on Yuki’s skin—red impressions where he had gripped her to keep her still. Evidence of the force required to restrain someone fighting against unbearable pain. He turned and walked out of the tent before anyone could see him vomit.

Ellen immediately moved to cover Yuki properly, adjusting sheets to preserve her modesty now that the medical necessity had passed. She checked Yuki’s pulse—elevated but strong and regular. She checked the surgical site—clean, no signs of immediate complications. The incision was closed with neat, precise sutures. In different circumstances, it would have been a textbook appendectomy. In these circumstances, it was something else entirely—a violation in the service of healing. Trauma inflicted to prevent death.

Recovery

The first forty-eight hours after surgery were critical. Yuki lay in the medical tent on a clean cot that Ellen had prepared, covered with sheets that smelled of soap and sunlight. Her surgical site had been bandaged with careful precision, white gauze wrapped around her abdomen like protection against the infection that could still claim her life even after the appendix had been removed.

Fever was the enemy now. If her body temperature climbed too high, if infection took hold in the surgical wound, if bacteria spread through her bloodstream, then everything they had done would be for nothing. She would die anyway. Only now she would die with the added trauma of surgery etched into her final days.

Ellen Cooper checked on Yuki every two hours, day and night. She monitored vital signs with the vigilance of someone who understood that medicine was not finished when the scalpel was put away—temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, the appearance of the surgical wound. Each measurement told a story about whether Yuki’s body was winning or losing the battle against infection.

On the morning of June 16, Yuki woke for the first time since the surgery. Her eyes opened slowly, struggling to focus in the filtered light of the medical tent. Pain radiated from her abdomen, sharp and insistent, but different from the pain before surgery. This was the pain of healing, not dying. Her body recognized the difference, even if her mind was still catching up.

Ellen was there immediately, kneeling beside the cot with a cup of water. She helped Yuki sit up just enough to take small sips, supporting her head with practiced gentleness. The water was clean and cool, drawn from the purified American supply. It tasted better than anything Yuki had drunk in months.

Yuki’s throat was raw from screaming. She tried to speak but could only manage a whisper. Ellen did not need words. She checked Yuki’s temperature with a thermometer under her tongue, counted her pulse at her wrist, examined the bandage for any signs of bleeding or discharge. The temperature reading showed 38.5°C—elevated but not dangerously so, normal for post-operative recovery. Ellen made a note in her medical log, recording the time and the measurement with the careful documentation that might someday protect them all from accusations.

Yuki watched Ellen work with an expression that held confusion and something that might have been the beginning of trust. This woman had been there during the surgery, had held her hand, had spoken words in a language Yuki did not understand, but in a tone that communicated care. Now, this same woman was monitoring her recovery with the attention of someone who genuinely wanted her to survive.

It contradicted everything Yuki had been taught about Americans. They were supposed to be cruel, indifferent to suffering, willing to let prisoners die from neglect. But this woman, this enemy nurse, was treating Yuki with the same care she would give to one of her own soldiers.

Ellen noticed Yuki watching her and offered a gentle smile. She spoke slowly in English, pointing to herself. “Ellen. My name is Ellen.” Yuki understood. She pointed to herself with a trembling hand. “Yuki.” “Yuki,” Ellen repeated, pronouncing it carefully. “You are going to be okay, Yuki. You are going to heal.” The words were in English, but the meaning transcended language. Yuki saw it in Ellen’s eyes—genuine concern, professional competence, human compassion that recognized no boundaries of nationality or politics.

For the first time since her capture, Yuki allowed herself to believe that she might actually survive this war.

Epilogue

The war in the Pacific ended on August 15, 1945, with Japan’s unconditional surrender. Yuki, now fully recovered from surgery, heard the announcement with mixed feelings—relief that the killing would stop, grief for her lost nation and lost family, uncertainty about what came next. She had no home to return to, no family waiting for her. She was twenty-four years old and utterly alone in a world that had been turned upside down. But she was alive. And that fact, simple as it was, meant everything.

On the day of her repatriation, Ellen brought Yuki a small origami crane folded from a scrap of American ration paper. “In Japan, crane means hope, healing, peace,” Yuki explained, tears in her eyes. “You give me life. I give you hope.”

Tom Bishop returned to Iowa in December 1945, carrying his duffel bag, his memories, and a small paper crane that he would keep in a wooden box for the rest of his life. He would marry, have children, farm the land his grandfather had homesteaded, and become a quiet, steady presence in his community—known for his gentleness and his reluctance to speak about the war. And every night before sleep, he would think about Yuki Nakamura, wonder if she had survived the chaos of postwar Japan, hope that she had achieved her dream of becoming a doctor, pray that she had found peace.

He would never know for thirty-three years that she had. That she had attended Tokyo Medical School, become one of Japan’s most respected emergency physicians, married, had children, and built a life that honored the second chance he had helped give her. He would never know until 1978, when a historian discovered a photograph in a manila folder and started asking questions. A photograph that appeared to show something terrible but actually captured something beautiful: a moment when humanity transcended hatred, a choice to save rather than destroy, a mercy cut that healed more than flesh.

And when Tom Bishop, sixty years old and widowed, received a phone call from Dr. Margaret Fleming asking if he remembered June 15, 1945, he would find that he remembered everything—every detail, every moment, every choice. And he would agree to meet Yuki Nakamura one more time, thirty-three years later, to discover what his mercy had created, to learn that the young nurse he had helped save had spent her life saving others, that the trauma he had inflicted had transformed into purpose, that the paper crane’s promise of hope had been fulfilled beyond anything he could have imagined.

But that reunion and all it would mean still lay decades in the future. For now, in December 1945, Tom Bishop simply went home to Iowa, to his mother’s fried chicken and apple pie, to the farm in the cornfields, to the life he had fought to preserve. And in Tokyo, Yuki Nakamura began the long process of rebuilding, studying, healing, becoming the doctor her father had dreamed she would be—living the life that had almost ended on a stretcher in Okinawa, saved by enemies who chose to see her not as Japanese or American, not as prisoner or soldier, but simply as a patient who needed help, as a human being whose life mattered.

And that, in the end, was the entire story—the only story that truly mattered. That in the midst of war’s worst horrors, individual people could still choose compassion, could still recognize shared humanity, could still believe that every life, regardless of nationality or circumstance, deserved to be saved. The mercy cut had been deep, but what it revealed was deeper still: the capacity for goodness that persists even when everything conspires to destroy it. The stubborn human insistence that life matters. That healing is possible. That hope survives, even in war.

End