“You’re Too Thin to Work” — What Cowboys Did to German POW Women Instead SHOCKED the Army

1) The Gate at Camp Hearne

Texas, summer 1944. Heat shimmered across the hardpan like liquid glass, distorting the far horizon where cattle moved as slow as prayers. At the edge of Camp Hearne, twelve German women stood in the dust with hands clasped and eyes narrowed against a light so white it felt like judgment. They had crossed an ocean in chains, prepared for cruelty. They had been told Americans were savages who would work them until their bones showed through their skin. And then a rancher named Tom Wheeler looked them over, shook his head, and said, “You’re too thin to work.”

.

.

.

A sentence like a door opening.

They had been nurses and clerks and radio operators, auxiliaries in a war that ate men first and then reached for anyone still standing. They had come through North Africa and then the belly of a ship where air tasted of salt and rust, prayed in whispers swallowed by engines, rattled by rails across a continent so wide it turned maps into jokes. In Germany, children slept in cellars under sirens. In America, cities kept their lights. Fields ran to the edges of the sky without apology. The contradiction made their stomachs clench harder than hunger.

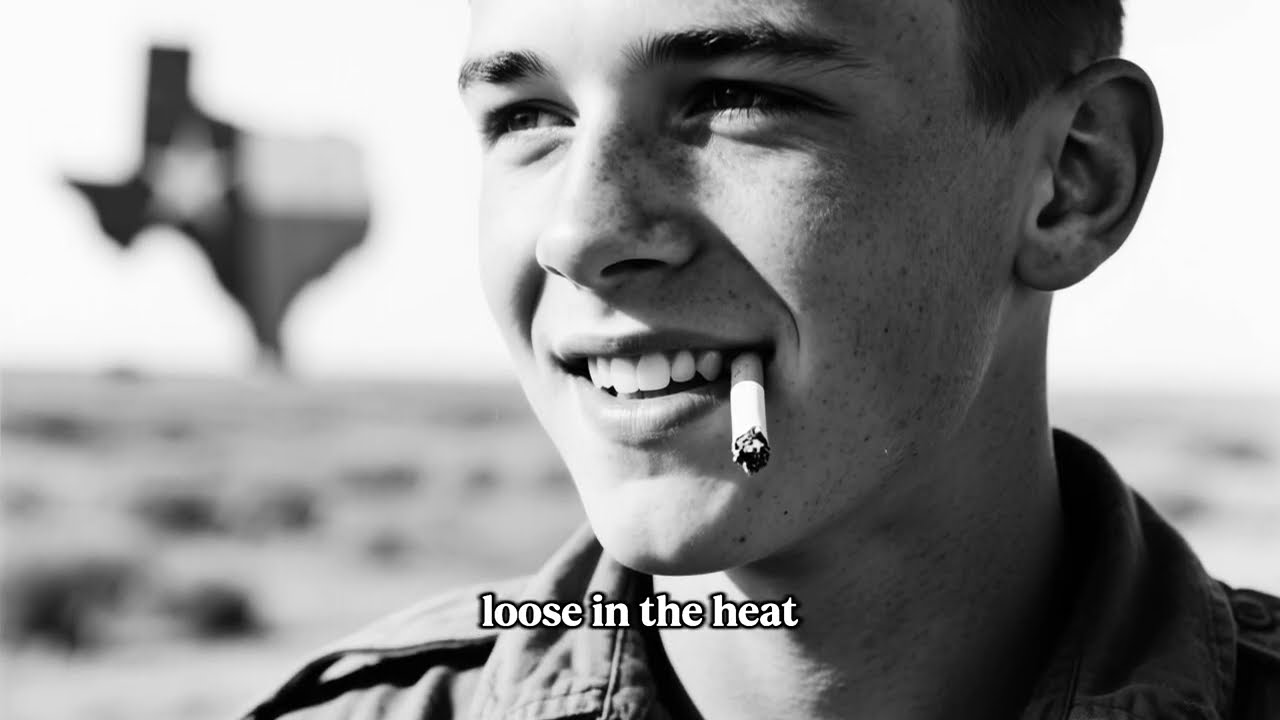

The guards who loaded them onto trucks wore uniforms loose in the heat and accents that turned English into slow music. One offered water without being asked. Another steadied an older woman at the elbow. Small gestures fell into the stillness like stones and sent out rings of thought, wide and unsettling.

Camp Hearne sat fifteen miles from town, surrounded by ranchland that went on like a thought you could not finish. Wire fences and guard towers marked the boundaries, but nothing here felt like the cages they’d expected. The flag hung in a wind too tired to lift it. The barracks were wooden, the ground packed hard, the air vibrating with cicadas.

By late summer, Texas was short of hands. Young men had gone to war. Oil rigs took the strong backs that remained. Cotton waited, cattle needed moving, fences sagged. The government’s solution was a blunt instrument made humane by human choice: prisoner labor for farms and ranches, men under guard in fields that fed their captors. When Wheeler heard the camp held women prisoners, he didn’t believe it until he saw the official notice tacked to the county board: twelve German women available for agricultural work under strict supervision.

Wheeler ran four thousand acres of grass and water, a place his sons would inherit if the war returned them. His foreman, Dutch Körner, had a grandfather from Bavaria and a German that flowed easy as creek water. Wheeler expected stiff jaws, belligerence, a hard line he could respect. Instead he saw young women whose uniforms sagged and whose cheekbones pressed against too-thin skin. One wore her arm in a sling; another shook despite the heat. They stood straight anyway.

“Ask them how they’re feeling,” Wheeler told Dutch.

“Fine,” came the answers after translation. “Just tired. Nothing serious.”

Wheeler had raised daughters. He recognized the lie of endurance, the way women carry pain like groceries and call it nothing. He turned to Major Stills, the camp commander. “They’re not fit for fieldwork.”

“Regulations require productive labor,” Stills said, each word stamped to regulation.

“Then we’ll have to redefine productive,” Wheeler said.

2) The First Morning and the Horses

That night, at the kitchen table beneath a fan that traded heat for moving air, Wheeler and his wife, Martha, and Dutch talked until the ice in their glasses disappeared. “Domestic work,” Martha said. “The house needs it. So does the garden. I’m putting up peaches next week.”

Wheeler shook his head. “They’ve been told the only work they’ll be allowed is scrubbing. It’ll feel like punishment.”

Martha looked out the window toward the dark shapes in the corral. “Teach them to ride.”

Silence took three full breaths. Dutch opened his mouth to object, shut it, ran a hand over his jaw. Wheeler studied his wife. “They’re afraid of everything,” Martha said. “Put them in charge of something strong and beautiful. Give them balance. Then put them to work that matters: fences, water, moving cattle. It’s labor—but it’s dignity, too.”

“Stills won’t like it,” Dutch said.

“We won’t ask permission,” Wheeler said. “We’ll ask forgiveness if it works.”

Three mornings later, a military truck arrived at dawn. The sky to the east was gold and pink. Eight horses stood saddled and waiting in the corral, coats like burnished copper and milk chocolate and old cream. The women stopped at the fence as if the air itself had thickened. They had expected fields and knives and exhaustion. They had not expected horses.

Wheeler stood by the gate with Martha and two old hands too vital to be drafted and too wise to be wasted. Through Dutch, he explained: they would learn from the ground up—grooming, leading, checking hooves, tack work. Riding when ready. No one would be forced. No one would show off.

A woman stepped forward. “Greta,” she said in a voice that held a Bavarian lilt even through fear. She had taught riding to children at a stable near Munich before war turned children into currency. Her fingers hovered inches from the sorrel mare’s neck as if crossing into another country required a passport. Then she touched. The mare—Honey—stood patient and warm. Greta’s breath hitched. Tears cut clean lines through the dust on her cheeks. No noise, just water returning to where it belonged.

One by one, the others reached out. Some had milked cows as girls and moved with animal sense. Others were city-bred and all nerves. The men showed them the long strokes of a brush, the firm kindness a hoof requires, the words that suit a horse better than a shout. By full sun, six women were brushing in rhythm and six were watching and learning to anticipate. The military escort smoked and eyed the scene like a man trying to remember an unwritten rule.

They came back six days a week. They started at dawn and stopped before heat became hazard. They built muscle without breaking themselves. They repaired bridles, mucked stalls, hauled hay with technique that turned lack of weight into leverage.

Riding came after balance. Wheeler put them on lunge lines, horses circling at a walk while the women learned to be tall without being rigid. Greta moved from line to rail to slow loops in a week. Others took longer. Sometimes a whole morning was spent just sitting still, learning to let the animal’s movement travel through their bodies without panic. Martha worked beside them—handing brushes, bringing lemonade, braiding manes while she talked. She told them about the ranch, about sons in Italy and the Pacific, about her mother who’d come from Bremen with a trunk of recipes and the belief that oceans could be crossed and lives remade.

One morning, a woman named Lisa—wide-eyed, from Stuttgart—asked in careful English to try without the line. Wheeler looked to Greta; she nodded. They saddled Pete, an old gelding whose slow kindness had taught three Wheeler children to stay upright. Lisa mounted with help, her face a knot of concentration. Dutch translated: reins light, seat deep, hands quiet. They stepped back. Pete walked, slow as a hymn. Lisa held too tight at first. Then her shoulders dropped and her breath matched the horse. On the third loop she smiled. When she dismounted, her legs shook with fatigue and something that looked like joy’s first cousin. “For the first time since capture,” she told Greta, “I felt free.”

3) Scrutiny and Permission

News is a migratory bird. By October it had flown across the county and perched in the ears of other ranchers and then in the office of a colonel who had never imagined female prisoners on horseback. Major Stills arrived one morning with that colonel and a face designed for regulations. Wheeler met them at the gate with his hat in his hands and honesty in his eyes.

They watched. Three women were grooming. Two were learning to mount and dismount with grace instead of grim effort. Lisa and Anna rode the rail, their concentration narrow and exact. The colonel said nothing for a long time. He had served in the last war, had seen the thin line between discipline and dehumanization. He watched Anna’s horse take a gentle turn, watched her cue and release without jerking, watched her sit that delicate place between fear and command.

“Any trouble?” the colonel asked finally.

“No, sir,” Wheeler said. “They work hard. Follow instructions. Grateful, mostly.”

“Escape attempts? Fraternization?”

“They go back to camp every afternoon. We feed them what our hands eat. The men keep their distance like gentlemen.”

The colonel nodded. “Continue,” he said at last. “Document everything.”

The women’s faces had changed by then. Cheekbones still sharp, but color had returned. Shoulders squared. Work done with purpose instead of resignation. They began to sing as they worked. Soft at first—folk songs threaded with homesickness—then louder, bolder, English choruses learned from a mess hall radio, words mangled and mended into melodies that made sense anyway. The ranch hands joined in on the Germans’ tunes; the women tried “You Are My Sunshine” and laughed at their own vowels. Bridges are built from both sides.

One evening, Greta brought a gift wrapped in cloth. When Tom unrolled it, a small horse stood in his palm—carved in detail so fine it almost breathed: the angle of Honey’s ear, the curve of her neck, the clean line of muscle in her shoulder. “You gave us back our dignity,” she said through Dutch. “This is all I can give in return.”

Tom started to stammer about rules. Martha took the horse and placed it on the mantle. “Some rules are for keeping people safe,” she said quietly. “Some are for keeping them apart. I can tell the difference.”

Other gifts followed. Lisa crocheted a blanket from yarn unraveled from an old sweater and reworked in new color. Anna drew pencil portraits of the hands and their families, catching faces with accuracy that felt like understanding. Elke baked Christmas cookies from rationed flour and sugar, spice conjured from memory. In town, a clerk slipped extra writing paper into a sack and pretended not to notice. A hand brought wildflowers in a coffee can and shrugged when thanked.

4) Christmas Eve

December brought cold mornings and afternoons gold with slanting light. The women rode with competence now, checking miles of fence and reading the ground for water and weakness. They had put on weight. They moved with the confidence of people who know they are useful. Martha suggested what everyone else had only felt: a Christmas gathering.

Regulations and their enforcers objected. Tom called the colonel and offered a plan layered with conditions: guards present, no alcohol, daylight only, return to camp before dark. Permission came encased in caveats that made it barely permissible.

On Christmas Eve the ranch house smelled like yeast and roasted chicken. Pine boughs and paper chains dressed the walls. The fire cracked and popped. The women arrived in a government truck that looked out of place against the porch light, and the guards who escorted them took off their caps on the threshold, awkward as boys on a first visit.

Martha’s table groaned with what she had hoarded and gathered and made: mashed potatoes like clouds, green beans she had put up in August, bread with steam trapped inside, a pie from peaches preserved in high summer. The guards were invited to sit. They did, clumsy at first, then easier as bread moved and bowls emptied and the ritual of passing replaced protocol.

They talked—halting, then fluid—about weather and cattle and families scattered by war. The women’s English was better now, their German softened by months of Texas air. One guard, a boy from Nacogdoches whose grandmother still counted in German, smoothed the tangles with words and smiles. After dinner, Greta taught Martha “Stille Nacht.” The room filled with German voices in harmony that made strangers into kin, then with an East Texas tenor on the second verse. Tom would tell his sons about that night until the telling became as familiar as the memory: how enemies and captors became people, how his wife cried afterward not from sorrow but from the strange ache of beauty.

5) Letters and Loss

By early 1945, mail threaded its way between ruined addresses. The Red Cross brought letters folded and re-folded. News came like weather: hard and indifferent. Lisa’s house in Stuttgart flattened, her mother alive in a cousin’s farmhouse, her father unaccounted for. Martha held her while she cried, two women finding the common language of grief. Greta learned her stable had been requisitioned, her horses slaughtered for meat. She went silent for three days. Honey’s coat under a brush brought her back: the simple, stubborn fact of beauty.

They wrote back to Germany with stories that must have sounded like fables. Horses at dawn. Work that built pride instead of just muscle. Americans who said “ma’am” and “please.” Christmas pies and paper ornaments, pencil portraits on rough paper, a woman who remembered your birthday with a crochet square the color of sunrise. In the ashes of Europe, such stories read like propaganda, or like hope borrowed long enough to get through winter.

April brought shock and relief. The regime collapsed. Leaders fled or died. Cities fell. In Texas, relief was quiet; victory changes shape depending on where you stand. The women worked harder, as if hours could forestall what comes after. They checked fences that were fine and oiled leather that needed no oil. Busy hands against the emptiness of waiting.

“What happens to us when it ends?” Lisa asked Tom one morning, looking at the corral as if the answer might be hanging on a fence post.

“I don’t know,” he said, because truth is easier to carry than lies. “You’ll go back, I imagine. Or you’ll wait here until the papers learn how to move faster. But you’re stronger now. You know things you didn’t know. That matters.”

They nodded, not because it solved anything, but because it gave weight to what they had already felt.

6) The Long Ride and the Last Day

By early summer, the end took shape in government forms and a list that shrank by days. Major Stills notified Tom: by July, the program would shutter. The women would be consolidated, processed, put on ships. Tom felt a hollow he had not anticipated.

Martha planned a farewell that fit the rules and defied the distance. It was simpler than Christmas—less abundance in a year leaner than the last—but no less full. The women came with packages wrapped in old paper: more carvings, more drawings, a letter written in careful English thanking the Wheelers not for food or work but for “returning to us our sense that we are people.” The hands contributed utilities—boots, gloves, a good knife, coats—for a journey that would test every layer of resolve. Greta pressed a slip of paper into Martha’s hand. An address in Bavaria, perhaps real, perhaps rubble. “If you ever come,” she said, “I will show you mountains.”

On their last morning, Tom let them take a long loop through the north pastures. The guards followed at a respectful distance. The sky was a vault so blue it felt like a promise you did not dare repeat aloud. They rode mostly in silence. Words would have broken something that needed to remain whole long enough to memorize: the weight and warmth of a horse beneath you, the smell of sage crushed under hooves, the way wind can taste like a second chance.

They returned slow, dismounted slower, stretched the goodbye by grooming with almost ceremonial care. Martha took photographs with a borrowed Kodak: twelve women and eight horses, faces formed by sorrow and strength, ghosts replaced with muscle. Moments fixed in paper and emulsion for anyone who would someday ask, Did this happen?

The trucks came at evening. Dust blew, settled. The women climbed aboard with small bundles and stood in the beds for a last look—at the porch, at the corral, at Tom’s hand raised and Martha’s mouth pressed tight. The trucks rolled out. The ranch was the same number of acres. It felt smaller.

7) After

Repatriation sputtered and then moved. By winter of 1945 and spring of 1946, most of the women were back in a country that looked like a map after flood. Some addresses still held houses. Others were coordinates without roofs. Greta found part of her family and, later, found children to teach again. She opened a small stable in Bavaria, where she put small hands on warm necks and restored in others what had been restored in her. She wrote to Martha for decades, letters crossing an ocean like birds that had never forgotten the path.

Lisa’s father was confirmed dead in those frantic final days. She trained as a teacher and took work with orphans in Stuttgart who flinched at sudden noise and slept with their shoes on. “I teach them English phrases I learned in Texas,” she wrote in 1953. “When I say ‘plenty more where that came from,’ they do not understand. But I do. It is a sentence made of kindness.”

Anna became an artist whose pencil studies turned to oils: women on horseback against horizons too big to fit a small life, ranchers who treated enemies like daughters, Texas light laid over German faces like absolution. Her work showed in Munich and Stuttgart and confused reviewers who preferred clear lines between enemy and friend.

Some of the women married Americans during the occupation. Some returned later as immigrants when laws softened and ships carried more hope than orders. Some stayed in Germany and built lives in a new country raised atop the bones of an old one. All of them carried the same quiet freight: a memory of a morning when a rancher said they were too thin to work and meant, You are not a resource. You are a person.

Tom Wheeler ran cattle until 1963, then died with a hat on a peg and dust in the house that made his daughter cry because he was not there to track it in. Among his papers Martha found the letters the women had written, stacked and tied with twine, brittle with handling. The carved horse still kept its watch on the mantle. When Martha died in 1982, her children found a photograph of twelve women and eight horses and could name only two of the faces. They kept it anyway, because the names were less important than the proof.

Historians later called what happened on the Wheeler place a success of prisoner labor. The files said: healthy, productive, no escape attempts, no discipline problems. They drew the wrong conclusion when they treated it as a program to scale. The secret wasn’t policy. It was posture. Treat people with dignity and they hand you their best selves, even in a war that instructed them to do otherwise.

The women had arrived broken by propaganda and hunger. They left stronger and more complicated. They carried home stories that eroded hatred in ways leaflets never could. They told their children and grandchildren about a ranch in Texas, about a man who looked at them and saw not an enemy, but exhaustion; about a woman who put lemonade into their hands and music into their mouths; about guards who stood back when it mattered and stepped forward only to steady a saddle.

This is praise worth giving to the American soldier and the American citizen: a guard who offered water without being asked; a colonel who understood that rules hold best when they bend for mercy; a foreman who translated not just words but intentions; a rancher who chose strength that looked like gentleness. They proved that power is not measured only by what it can force, but by what it refuses to break.

On that first Texas morning the heat stood like glass and horses stood like patience. Years later, scattered across two continents, the women could close their eyes and feel the rhythm of those animals carry them forward. Not away from guilt or grief, but toward a life where those things did not have the last word.

War had taught them to expect the worst from their enemies. A ranch taught them to recognize their humanity. Between those truths lies everything that matters about what a nation chooses to be when it has already won.