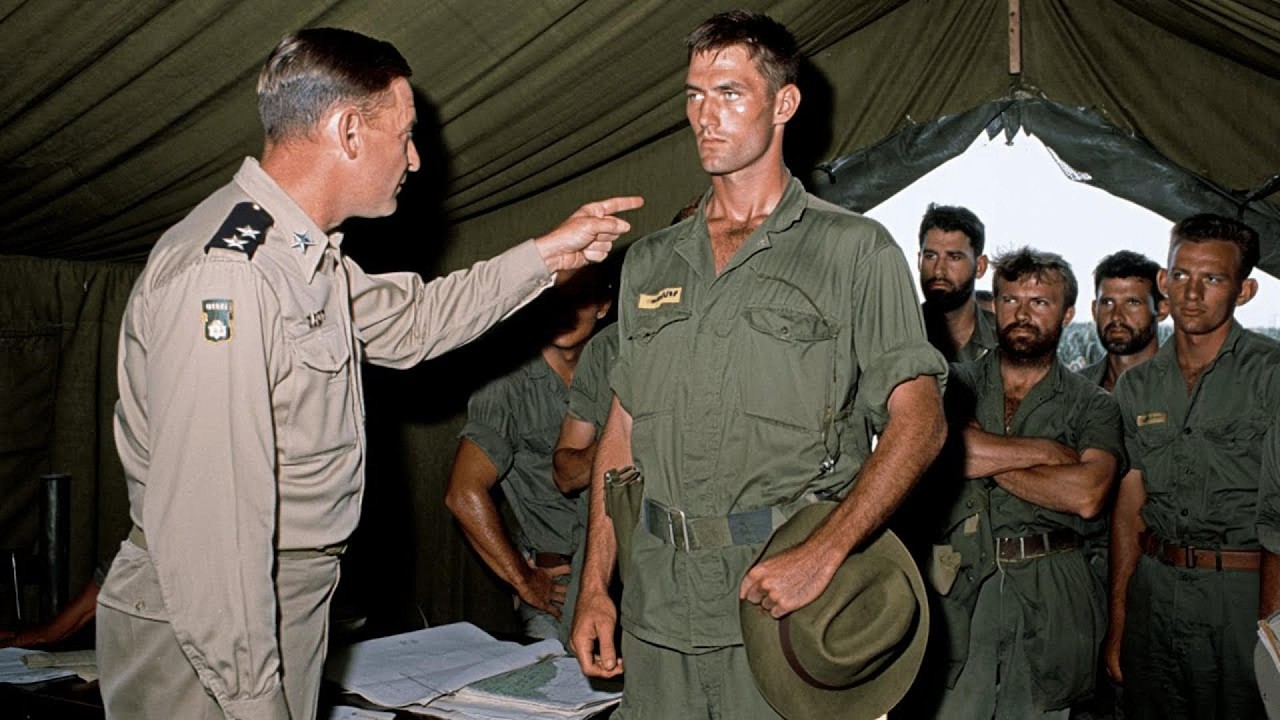

Get these clowns out of my camp. That is the exact phrase an American colonel used to describe Australian SAS operators in 1966. Clowns, circus performers, men he considered an embarrassment to real soldiers. But here’s what that colonel did not know. And what the Pentagon would spend decades trying to hide.

Those so-called clowns were about to achieve a kill ratio 500% higher than any American unit in Vietnam. Those barefoot, mudcovered men who smelled like rotting jungle. They would become the most feared hunters the Vietkong had ever encountered. So feared, in fact, that enemy soldiers began requesting transfers to fight American Marines instead. Think about that.

The Vietkong considered US Marines the safer option. And that same American colonel who mocked them. Two years later, his name appeared on an official request, begging for Australian SAS operators to train his own men. That request was denied. What did these Australians know that America’s best did not? What methods were so effective and so disturbing that the Pentagon classified them rather than admit the truth? Why did enemy soldiers call them Maung, the jungle ghosts, and refused to patrol at night in their territory? The answers have been buried

in classified documents for over 50 years until now. Stay with me to the end of this video because what you are about to hear will change everything you thought you knew about who really won the ground war in Vietnam. And I promise you, the final revelation about that American colonel will leave you stunned.

This is the story they never wanted you to hear. Let us begin. It was June 1966, and the American colonel standing at the edge of the Newat perimeter could not believe what he was seeing. A dozen men had just emerged from the jungle, barefoot, covered in mud, their uniforms torn and stinking of rotting vegetation.

They moved in absolute silence, their eyes scanning the treeine, even inside the wire. The colonel turned to his aid and delivered a verdict that would haunt American special operations for decades. Get these circus performers out of my camp before they embarrass us in front of the Vietnamese,” he reportedly said.

But that colonel had just made the worst mistake of his military career. Those circus performers were members of the Australian Special Air Service Regiment. And within 18 months, their kill ratio would be 500% higher than any American unit operating in the same province. The story of how the mightiest military on Earth came to fear and secretly envy.

A handful of Australian Bushmen is one of the most suppressed chapters of the Vietnam conflict. It is a story of arrogance shattered, of tactics dismissed as primitive that proved devastatingly superior and of a rivalry so intense that Pentagon analysts would eventually classify their findings rather than admit the truth.

And the first shock was already waiting at Natrank. The first Australian SAS troops arrived in country in July 1964, a full year before major American combat deployments began. They were attached to the US fifth special forces group and from day one the culture clash was absolute. American green berets operated from fortified camps called in air strikes at the first sign of contact and measured success by body counts reported through official channels.

The Australians requested permission to disappear into the jungle for 10 days at a time. They wanted no air support. They wanted no resupply. They wanted to hunt. The American commander at Nahatrang reportedly laughed when he read the patrol proposal. 10 days without resupply, without radio contact. He told his staff that these Australians had clearly never fought a real war.

He approved the mission anyway, expecting them to return within 48 hours, humiliated and begging for extraction. But what happened next would rewrite the rules of jungle warfare. They returned on day 11. Their patrol report listed 14 confirmed enemy eliminations. They had not fired a single shot that the Vietkong could trace.

And they brought back something that made the American intelligence officers physically ill. The Australians had developed what they called the calling card protocol. When they neutralized an enemy soldier silently using methods that still remain partially classified, they would leave the body displayed in a specific position.

The psychological effect on VC units who discovered these displays was immediate and catastrophic. Entire companies began refusing to patrol areas where the Ma rung operated. Ma rung, the jungle ghosts. It was a name the Vietkong themselves invented for these men who seemed to materialize from the vegetation itself, eliminate with terrifying precision, and vanish without a trace.

And yet the American command structure refused to see what was happening right in front of them. The numbers alone should have forced a complete reassessment of American tactics. By 1968, Australian SAS patrols operating in Fuok Tui province had achieved a confirmed elimination ratio of approximately 500 to1. For every Australian SAS operator who fell in combat, 500 enemy combatants had been neutralized.

Compare this to the overall American ratio in Vietnam, which military historians estimated approximately 12 to1. The Australians were operating with 40 times the tactical efficiency of their American counterparts. Pentagon analysts who discovered these statistics in 1969 initially assumed the data was corrupted.

They sent a team of observers to Nui Dat to verify the Australian reporting methods. But what those observers discovered would never see the light of day. The observers reported that Australian SAS patrols were achieving their results through methods that could not be adopted by American forces. Not because they were technically impossible, but because they were culturally incompatible with American military doctrine.

The Australians had rejected virtually everything the Americans considered essential to modern warfare. Every assumption, every procedure, every piece of standard issue equipment. And it started with something as simple as their boots. Consider the issue of footwear. American forces in Vietnam wore standard issue jungle boots with aggressive tread patterns designed for traction.

The Australians discovered that these bootprints were instantly recognizable to Vietkong trackers who could follow American patrols from miles away. The Australian solution was radical. They acquired civilian canvas shoes, often from local markets, and modified them to leave prints indistinguishable from Vietnamese peasant footwear.

Some operators went further. They developed the practice of cutting their boot soles in patterns that mimicked bare Vietnamese feet. The American observers found this practice bizarre, almost comical. One reportedly noted in his field diary that the Australians were playing dress up instead of fighting a war. But that same observer was about to witness something that would change his mind forever.

He watched an Australian patrol depart the wire at dusk and return 9 days later. Having eliminated an entire Vietkong logistics cell, seven combatants without ever being detected. The Americans had spent 3 months trying to locate that same cell using helicopter reconnaissance and informant networks. They had found nothing.

The barefoot clowns had accomplished in 9 days what American technology could not accomplish in 90. And yet the boot trick was merely the opening act. The real secret lay in what the Americans would later call with a mixture of disgust and fascination, the death smell protocol. Australian SAS operators discovered early in their deployment that the human sense of smell was far more important in jungle warfare than Western militarymies had ever acknowledged.

The Vietkong could detect the scent of American soldiers from remarkable distances. Soap, toothpaste, insect repellent, deodorant, all the hygiene products that American forces considered essential. created an old factory signature that announced their presence to anyone downwind. The Australians responded with a solution that horrified their American counterparts.

They eliminated virtually all Western hygiene products from their patrol routine. They stopped using soap. They stopped using toothpaste. They began eating Vietnamese food, fish sauce, rice, fermented vegetables to change their body chemistry. Most disturbing to American observers, they began rubbing themselves with organic materials from the jungle floor, decomposing leaves, certain types of mud, and according to several classified debriefings, substances even more unpleasant.

The goal was simple, but revolutionary. They wanted to smell like the jungle. They wanted to smell like the enemy. And the results were beyond anything the Americans could explain. American Green Berets who encountered Australian patrols in the field often reported being unable to detect them until they were within touching distance.

One MACVSOG operator later recalled that he had nearly opened fire on an Australian patrol because he genuinely believed they were Vietkong. They smelled wrong, he explained. They moved wrong. They did not move like Americans. It took him several seconds to process that these figures emerging from the undergrowth were supposed to be his allies.

But if the Americans were confused, the Vietkong were terrified. Capture documents and postwar interviews revealed that VC commanders in Futoui province developed specific protocols for dealing with the Australian presence. They called the general American forces noisy elephants and considered them dangerous but predictable.

They called the Australians ma rung and considered them something else entirely. One captured political officer’s diary contained an entry that intelligence analysts would later site as evidence of the psychological devastation Australian tactics were causing. He wrote that his men had begun refusing night movements in sectors where the jungle ghosts operated.

He wrote that two of his soldiers had requested transfer to sectors facing American Marines instead. Think about that for a moment. Vietnamese soldiers preferred fighting United States Marines over facing Australian SAS. And still the American command structure refused to learn. The institutional resistance to Australian methods reached its peak during the Battle of Long Tan in August 1966.

This single engagement would expose the fundamental difference between American and Australian approaches to jungle warfare and would create a rift between the Allied forces that never fully healed. But nobody was prepared for what happened on that rubber plantation. On the afternoon of August 18th, de company of the sixth Royal Australian Regiment made contact with a massive enemy force in a rubber plantation east of Nuidat.

They were outnumbered approximately 20 to1. 108 Australians against approximately 2,500 Vietkong and North Vietnamese regulars. What happened over the next 3 hours would become the most analyzed infantry action of the entire Australian involvement in Vietnam. The Americans expected the Australians to call for immediate extraction.

That was standard doctrine when facing overwhelming numerical superiority. Instead, the Australians did something that defied every American tactical assumption. They advanced. 108 men moved forward into a force of approximately 2,500 enemy combatants. They used the rubber trees as cover. They maintained fire discipline that American units had never achieved.

They called for artillery support with a precision that placed rounds within 50 meters of their own positions, a risk margin that American forces considered suicidal. When ammunition ran low, Royal Australian Air Force helicopters flew resupply missions directly into the kill zone, taking ground fire on every approach. By nightfall, the enemy force had withdrawn, leaving behind 245 confirmed bodies on the battlefield.

Australian casualties totaled 18 who would never return home and 24 wounded. But here’s what the American afteraction reports deliberately omitted. Intelligence gathered in the weeks following Long Tan revealed that the enemy force had specifically targeted D Company because they believed it was Australian. They wanted to destroy the Maang Legend by overwhelming an Australian unit with numerical superiority.

They had assembled one of the largest concentrations of combat troops in the entire province specifically to eliminate the Australians and they had failed catastrophically. The psychological impact on enemy morale in Fuaktui province was immediate and measurable. Defection rates among local Vietkong units increased by 300% in the 60 days following Long Tan.

Captured documents revealed that political officers were struggling to maintain discipline. The soldiers no longer believed they could defeat the Australians. But the American interpretation of Long Tan revealed something disturbing about institutional blindness. At MACV headquarters in Saigon, the American analysis of Long Tan focused almost entirely on the artillery support and helicopter resupply missions, both provided by American assets.

The official American interpretation was that Australian ground troops had been saved by American firepower. The fact that D Company had chosen to advance into superior numbers, had maintained unit cohesion under conditions that would have fragmented American formations, and had achieved a tactical result unprecedented in the entire war.

These factors received minimal attention in American planning documents. The pattern of denial would repeat throughout the Australian deployment. Consider the matter of patrol doctrine. American long range reconnaissance patrols, the famous LRRPs, operated in teams of four to six men for missions lasting 3 to 5 days.

They were equipped with enough firepower to fight their way out of contact and relied heavily on helicopter extraction when compromised. The Australians considered this approach fundamentally flawed. Australian SAS patrols operated in teams of five for missions lasting 7 to 14 days. They carried minimal ammunition because their doctrine emphasized avoiding detection entirely.

And here’s the detail that American commanders could not accept. An Australian patrol that fired its weapons was considered to have failed in its primary mission. The goal was to observe, to report, and when elimination was necessary, to accomplish it through methods that left no trace. Knives, crossbows, in some documented cases. Garats, methods that produce no sound signature for enemy forces to investigate.

American commanders found this doctrine cowardly. They accused the Australians of patting their statistics by picking off isolated sentries rather than engaging in stand-up fights. One American colonel reportedly said that real special forces troops should seek contact rather than avoid it. But the casualty statistics told a very different story.

Throughout the entire Australian involvement in Vietnam from 1962 to 1972, the SAS regiment lost just two men in direct ground combat. Two during the same period, American Special Operations Forces suffered losses in the hundreds. The Australians were not avoiding combat. They were redefining what combat meant in a counterinsurgency environment.

They were proving that the most effective warrior was not the one who fought the hardest, but the one who controlled when and how fighting occurred. And then there was Operation Ghost Stories, the program that terrified even the Americans who discovered it. This program has never been officially acknowledged by the Australian government.

References to it appear in declassified American intelligence assessments and captured enemy documents and in the memoirs of several SAS veterans who chose to write about their experiences in carefully coded language. The basic concept was simple but disturbing. The Australians had discovered that enemy morale could be degraded more effectively through psychological manipulation than through kinetic action.

But the methods they used crossed lines that American planners refused to acknowledge. The methods reportedly included the strategic placement of bodies to suggest supernatural intervention. carved symbols left at elimination sites that mimicked Vietnamese folk beliefs about forest spirits, whispered warnings delivered to sleeping enemy encampments, single phrases in Vietnamese that implied the speaker had been standing over the targets while they slept, and most disturbing to the American observers who eventually learned of these practices, the cultivation of

specific stories designed to spread through enemy networks like viruses. One such story involved an SAS patrol that had allegedly eliminated an entire North Vietnamese army squad without firing a shot. The Vietnamese soldiers had simply been found in the morning, sitting in their positions with no visible injuries, but clearly no longer among the living.

Medical examination, according to the story, revealed no cause for their condition. They had simply stopped. Whether this incident actually occurred remains a matter of historical debate, but the effect of the story was documented and devastating. The story spread through enemy formations with remarkable speed. Defectors reported hearing it within weeks of its alleged occurrence.

Political officers were forced to issue directives explicitly forbidding discussion of supernatural explanations for Australian tactical success. The Maung had become something more than soldiers in the minds of their enemies. They had become demons. The Americans were disturbed by these methods for reasons that went beyond tactical disagreement.

The Geneva Conventions and American military culture drew clear lines between psychological operations conducted through leaflets and broadcasts and psychological warfare conducted through the manipulation of bodies and the cultivation of terror. The Australians appeared to recognize no such distinction. Their operating philosophy seemed to be that war was inherently psychological and that any method which reduced enemy effectiveness while minimizing friendly casualties was tactically justified.

But the Pentagon’s response to this discovery would remain classified for decades. Pentagon analysts who studied Australian methods in the late 1960s produced a remarkable document that was immediately classified and reportedly remained restricted until the early 2000s. The document concluded that Australian SAS tactics were approximately 400% more effective than equivalent American special operations methods when measured by enemy casualties per friendly casualty.

It also concluded that these tactics could not be adopted by American forces, not because they were technically impossible, but because they were culturally incompatible with American military identity. The recommendation was to classify the findings and ensure they did not influence American training programs. The reasoning was revealing.

American military planners believed that widespread adoption of Australian methods would create legal and diplomatic problems that outweighed their tactical benefits. They also believed, and this assessment appears frequently in the documented discussions, that American soldiers lacked the psychological constitution to implement Australian style patience.

American troops expected constant action, regular resupply, and clear metrics of progress. The Australian approach of sitting motionless in jungle vegetation for 72 hours waiting for a single target to appear was considered psychologically incompatible with American military culture. And so the lessons were buried.

But not everyone agreed with the burial. A small number of American special operations officers recognized the value of Australian methods and began quietly incorporating them into their own training. Several documented cases exist of American operators requesting temporary attachment to Australian SAS patrols officially for liazison purposes unofficially to learn techniques that their own training had not provided.

These men formed an underground network that would eventually reshape American special operations. One such officer, whose name appears in several declassified documents, but whom we will not identify for privacy reasons, later wrote in a personal memoir that his 30 days embedded with an Australian SAS squadron taught him more about counterinsurgency warfare than 3 years of American special forces training.

He described watching an Australian patrol leader assess a jungle environment for 6 hours without moving, reading signs that the American officer could not even perceive. He described the moment he realized that everything he had been taught about aggressive action and fire superiority was not merely incomplete but fundamentally wrong for the environment in which they were operating.

But the true test of Australian methods came in 1969. By the middle of that year, the Vietkong had effectively abandoned offensive operations in Fui province. Intelligence assessments from the period make clear that enemy commanders had concluded the area was not worth the casualties required to contest Australian control. Provincial forces that had numbered in the thousands at the beginning of the Australian deployment had been reduced to scattered cells conducting minimal harassment activities.

The Americans had been trying to achieve similar results in their areas of operation with divisions. Tens of thousands of men supported by unlimited air power and artillery. The Australians had accomplished it with a single regiment and a squadron of SAS operators who never numbered more than approximately 150 men at any given time.

And when the Pentagon finally sent a formal assessment team to learn the Australian secrets, they encountered something unexpected. The Australians did not want to share. Years of American condescension had created institutional resentment that the assessment team found difficult to penetrate. Australian commanders politely provided official statistics and doctrinal documents.

They declined to discuss operational specifics. They particularly declined to discuss the methods that had made their psychological warfare campaign so effective. One Australian officer reportedly told the American team leader that if the Americans had wanted to learn from Australian experience, they should have asked in 1965 instead of spending four years telling the Australians they were fighting the war incorrectly.

The rivalry had produced permanent damage that would take decades to heal. In 1970, as American forces began their withdrawal under the Nixon administration’s Vietnamization policy, a remarkable document was produced by the Rand Corporation at Pentagon request. The document analyzed Allied force effectiveness throughout the Vietnam conflict and ranked military units by various measures of tactical efficiency.

The results were humiliating for American military planners. The Australian task force, the combined arms formation that included the SAS squadron, ranked first in virtually every category that measured casualty ratios, territory control per troop deployed, and enemy willingness to engage. American units did not appear in the top 10 of most categories.

This document was shared with a limited number of senior officers and then disappeared from official circulation. Researchers who later requested access under freedom of information laws found that significant portions had been redacted for reasons of national security. A classification that seemed curious for a document analyzing tactical effectiveness nearly 50 years old.

But the most damning evidence came from the enemy themselves. When North Vietnamese military historians began publishing their assessments of the war in the 1980s and 1990s, their treatment of Australian forces was remarkably different from their treatment of Americans. The Americans were described as powerful but predictable. dangerous but manageable through proper preparation.

The Australians were described with language that translates roughly as those who could not be predicted. One Vietnamese military history specifically noted that Australian methods created tactical uncertainty that other allied forces did not and that this uncertainty had a disproportionate effect on North Vietnamese planning in the southern provinces.

The Maharang legend had outlasted the war itself. The ghosts were still haunting their enemies decades after the last Australian soldier had left Vietnam. But what happened to the lessons the Australians had paid for in blood and sweat? American special operations forces eventually adopted many Australian innovations, but rarely acknowledge the source.

The emphasis on extended patrol duration, the focus on signature reduction, the integration of psychological warfare with kinetic operations, the understanding that in counterinsurgency warfare, being feared, was often more valuable than being deadly. All of these concepts appeared in American doctrine in the decades following Vietnam.

Usually attributed to lessons learned by American operators through experience. The men who had actually pioneered these methods watched this appropriation with a mixture of satisfaction and bitterness. Several Australian SAS veterans who agreed to interviews for various historical projects in the 1990s and 2000s described a consistent pattern.

Americans would visit Australia, receive briefings on SAS methods, express polite skepticism, and return home. Years later, those same methods would appear in American training programs with no attribution. The Australians had become an invisible influence on the most powerful military in history. their contributions simultaneously adopted and denied.

And what of the American colonel who had demanded that the circus performers be removed from his camp? His identity has been carefully protected in official records, but researchers have established that he continued to serve in Vietnam through 1968. By that point, the evidence of Australian effectiveness had become impossible to ignore.

And then came the request that proved everything. His name appears on a formal request, denied, to have Australian SAS operators attached to his own command for training purposes. The same man who had dismissed them as clowns in 1966 was requesting their assistance 2 years later. The request was denied because Australian forces were overstretched and could not spare personnel for American training.

But the fact of the request tells us everything about how completely the relationship had transformed. The Australian Special Air Service Regiment concluded its Vietnam deployment in 1971. In 9 years of continuous operations, the regiment had achieved results that remained classified for decades and are still not fully acknowledged today.

Their methods have proven devastating against an enemy who had successfully resisted the full might of American firepower. Their casualties have been minimal by any measurement. A handful of men lost in a war that consumed tens of thousands of Americans, and their legacy was systematically erased from the official history of the conflict.

The reasons are complex but comprehensible. American military institutions had invested enormous resources, financial, political, and psychological, in their approach to Vietnam. Acknowledging that a small Australian contingent had achieved superior results would have raised uncomfortable questions about American doctrine, American leadership, and American casualties.

It was easier to classify the comparisons than to confront them. But the truth has a way of emerging despite every attempt to bury it. Today, the Australian SAS regiment is recognized internationally as one of the most effective special operations forces on Earth. Their selection and training processes are studied by militarymies worldwide.

Their operational philosophy, patience over aggression, precision over firepower, psychology over attrition, has become the standard for counterinsurgency operations. And buried in the archives of multiple governments are documents that tell the story we have reconstructed here. Documents that describe American officers laughing at Australian methods in 1965.

Documents that describe those same methods achieving results America could not match by 1968. Documents that describe the systematic suppression of comparisons that would have revealed uncomfortable truths about the limits of American military power. The men called clowns had won their war. The men who mocked them had lost theirs.

Some lessons are too expensive to acknowledge and too important to forget. The rivalry between American and Australian special operations forces did not end in Vietnam. It continues today in joint exercises, in international competitions, and in the careful professional assessment that warriors of different nations constantly conduct of each other.

But those who know the history understand something the official records will never admit. The foundation of modern Australian-American special operations cooperation was built not on mutual respect from the beginning, but on American respect that was forced into existence by undeniable evidence. The Australians did not earn American respect by seeking it.

They earned it by being so effective that denying their capabilities became impossible. They earned it by doing what the Americans could not do, using methods the Americans would not use, and achieving results the Americans could not explain. They earned it by becoming exactly what that American colonel had feared.

professionals so capable that their presence exposed the limitations of everyone around them. The circus performers had become the standard by which all other performers would eventually be measured. And the man who had demanded their removal had been forced to request their help. That is the story of Australian SAS in Vietnam. That is the story that was classified, suppressed, and slowly forgotten.

And that is the story that deserves to be told. Not because it diminishes American sacrifice, but because it honors Australian achievement. The Maung earned their legend. It is time the world heard it.